To the left of the main entrance of St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City stands a controversial bronze door that does not celebrate victory, salvation, or triumph. Instead, it confronts visitors with something the Church has rarely chosen to depict so directly: death itself.

Known as the Porta della Morte, or the Door of the Dead, it is the most contentional modern artworks on display in Vatican City as well as one of its most unique architectural elements created in recent memory. The defining work of the Italian sculptor Giacomo Manzù, the door was installed in 1964 in the doorway traditionally used as the exit for funeral processions in the basilica.

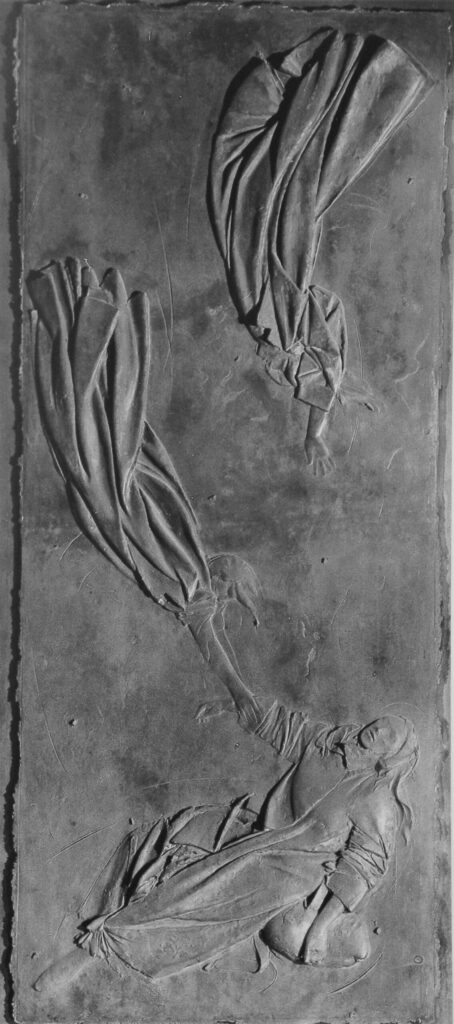

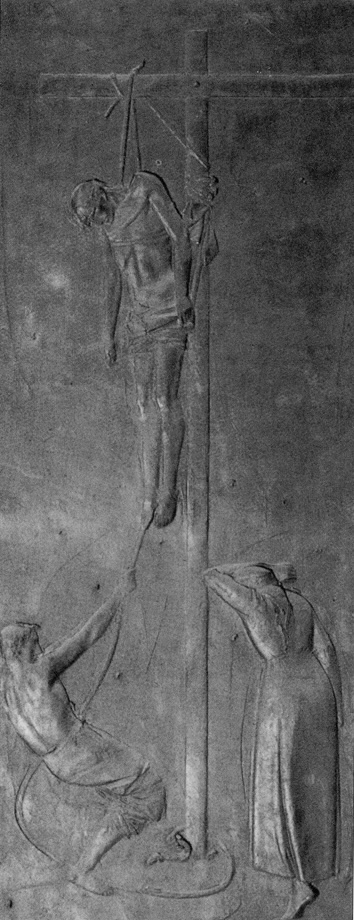

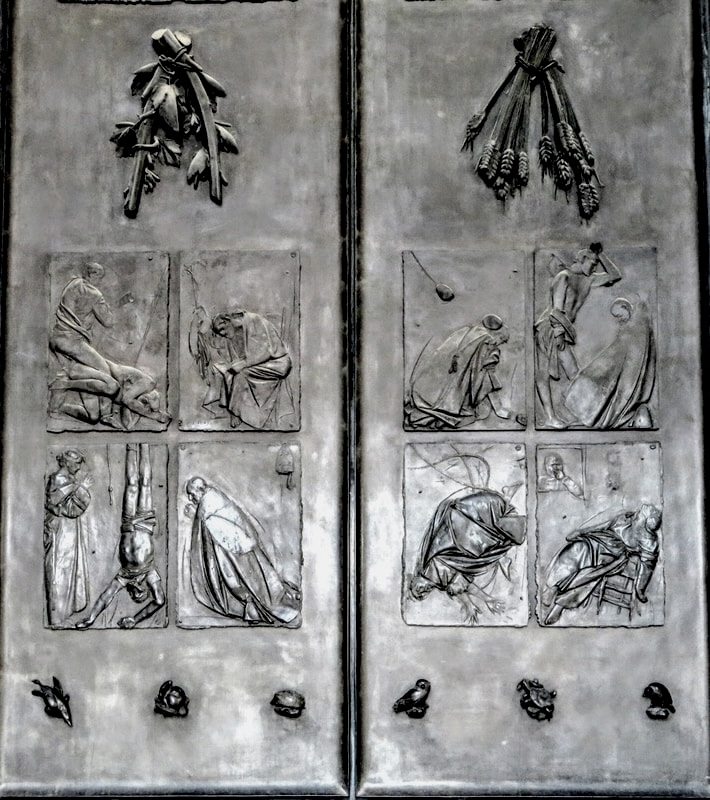

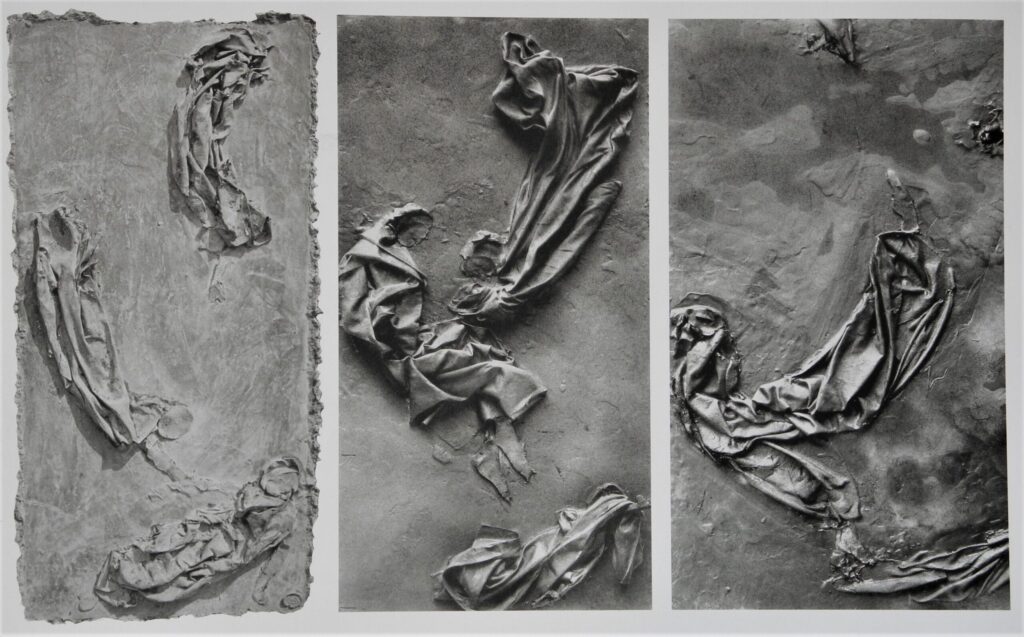

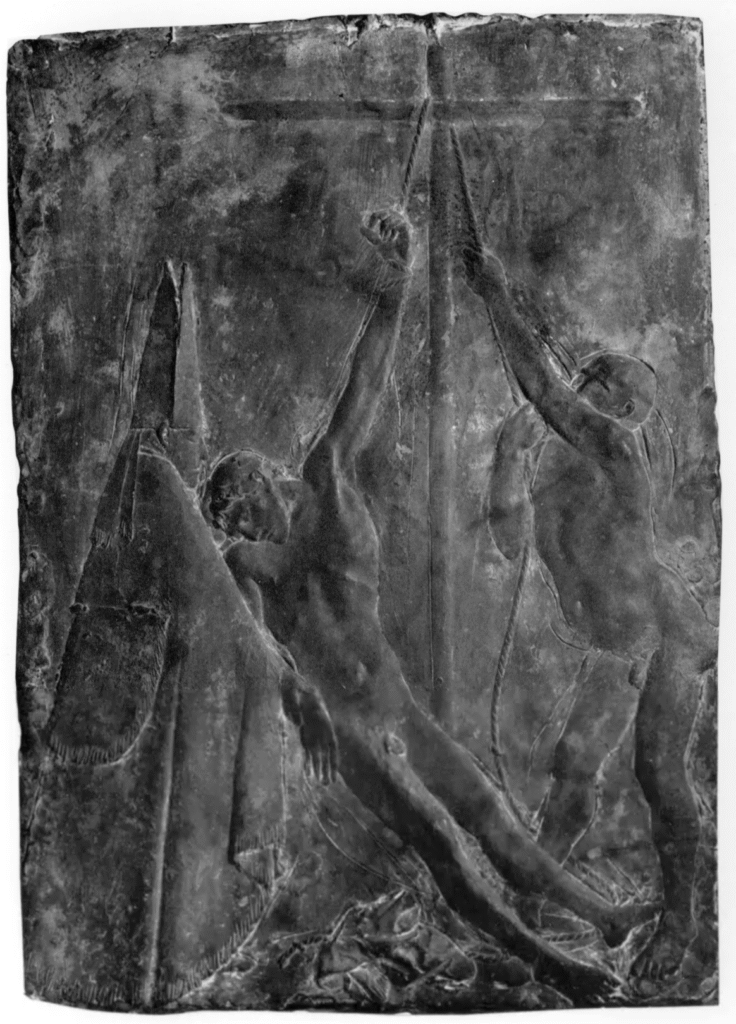

Measuring 20 feet in height, the door is composed of ten bronze reliefs arranged in five rows, framed by a vertical motif of vine and wheat, the Eucharistic symbols of wine and bread. At the top are the Death of Christ and the Death of Mary, rendered in elongated, almost weightless forms that remain legible even from the steps of the basilica.

Below, biblical and ecclesiastical deaths are interwoven with modern tragedies: Abel murdered by his brother, the quiet passing of Saint Joseph, the martyrdom of Saint Stephen, the deaths of Saint Peter and Pope Gregory VII, and the recent death of Pope John XXIII himself, included as an explicit act of homage.

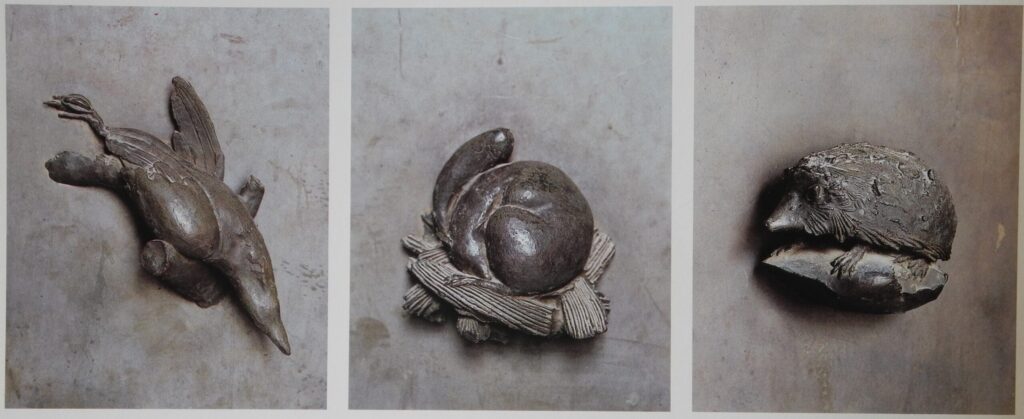

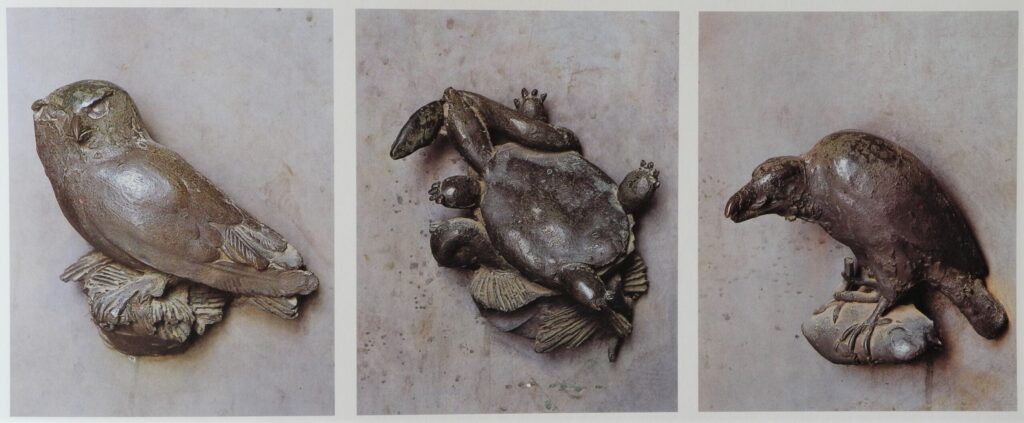

At the base of the door, almost invisible to the hurried visitor, six animals are modeled in low relief: a blackbird, a dormouse, a hedgehog, an owl, a tortoise, and a raven. Drawn from medieval symbolic tradition, they evoke sleep, time, vigilance, decay, and foreknowledge, quietly reinforcing the theme of mortality.

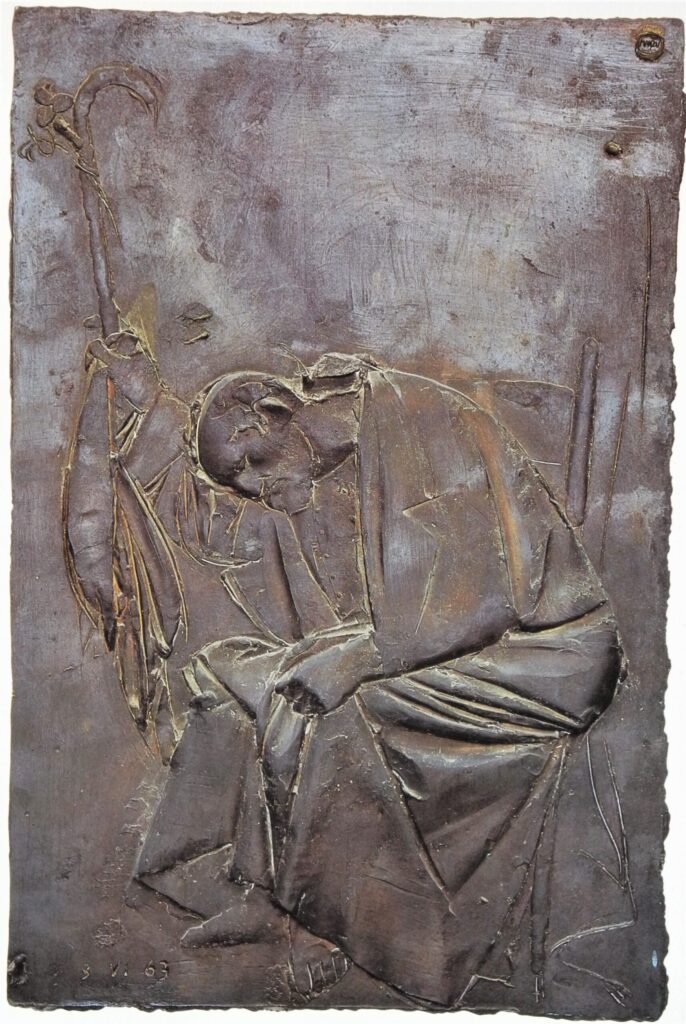

On the reverse side, facing the interior of St. Peter’s, Manzù depicted the opening procession of the Second Vatican Council, the defining moment of John XXIII’s pontificate. The long relief includes the Pope himself as well as Don Giuseppe De Luca, a subtle dedication to the sculptor’s close friend and iconographic advisor, who died before the work was completed.

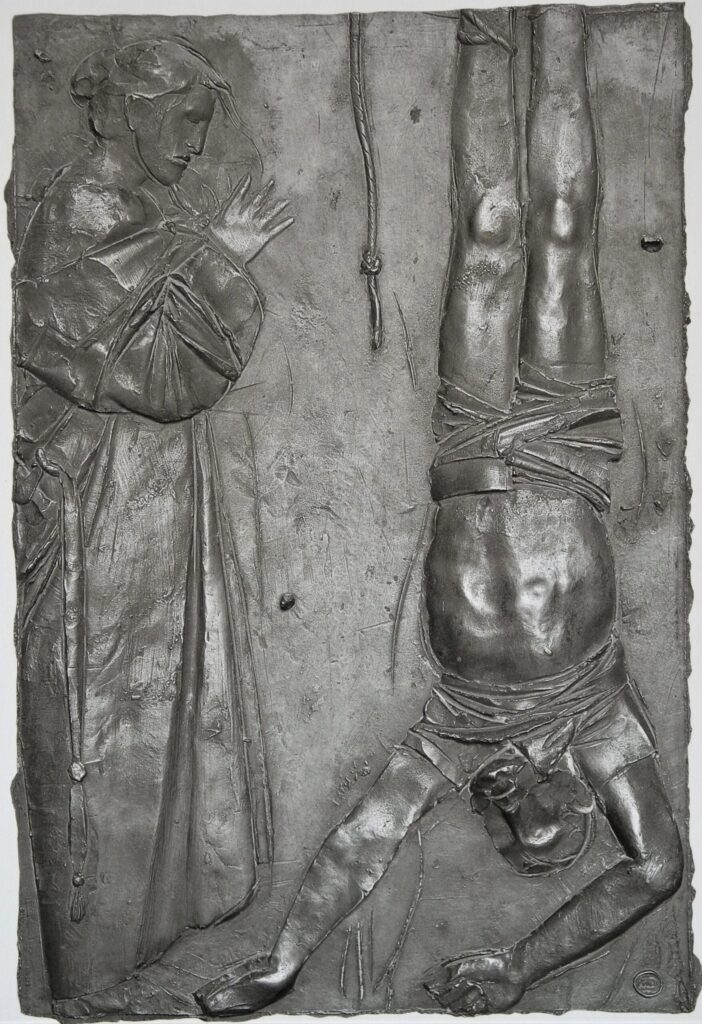

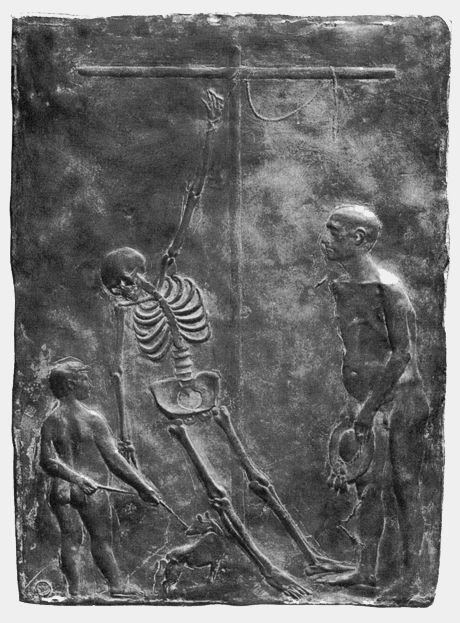

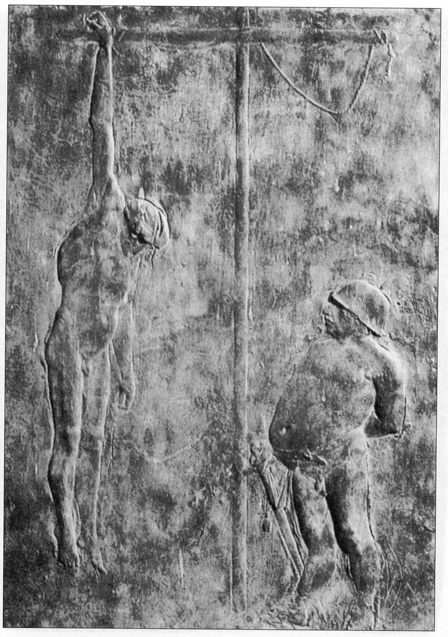

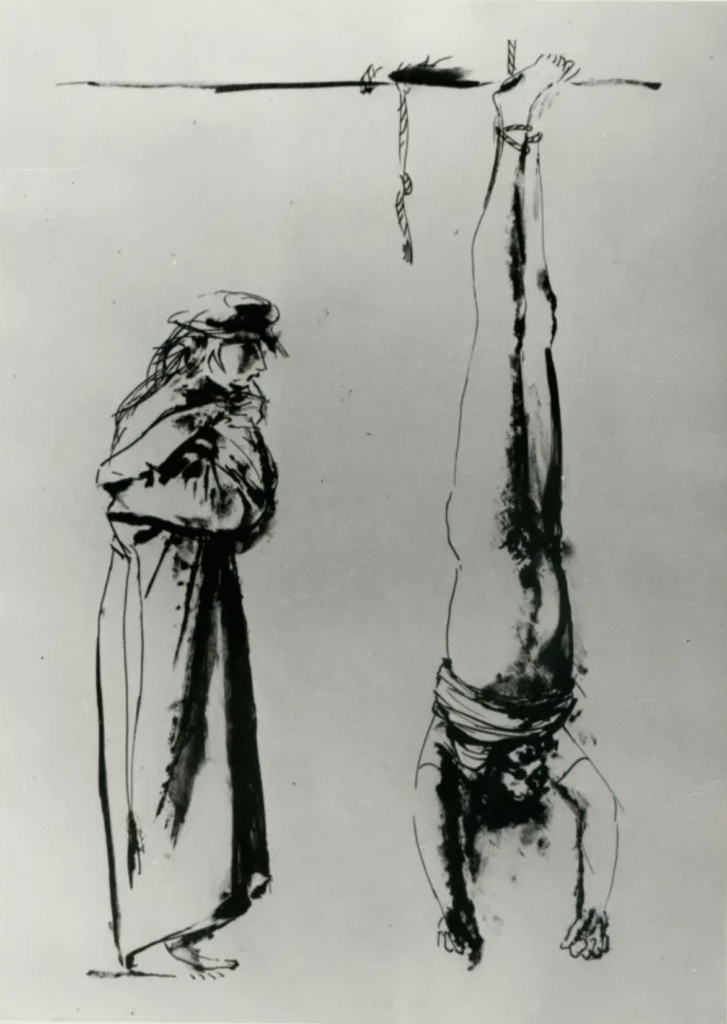

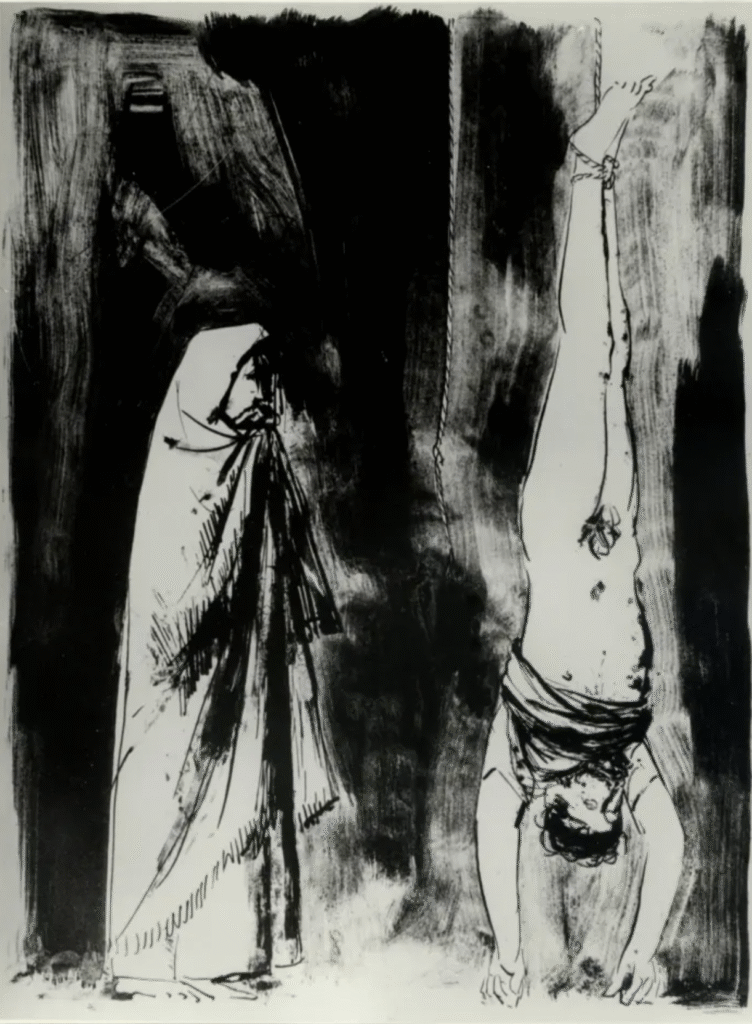

However, most controversial was the lower section of the outside, which depicts scenes not strictly related to Christianity but rather the horrors of history and nature: death by violence, death in the air, death on earth, as well as the death of Pope John XXIII as a tribute to the pontiff who had supported the door’s creation and who was unable to live to see his work completed. One panel in particular drew especially strong criticism, in which a cardinal gazes at a man hanging upside down, allegedly referencing the hanging executions of Italian fascists after the Second World War.

Another alludes to anonymous deaths in war and modern catastrophe, a visual reference to the violent political and social reckonings of Italy at that time. Despite the protests of some clergy, Manzù maintained his creative vision, even denying the request of one prelate to include latin inscriptions to accompany the images of Christ, Mary, and the saints, stating “I can’t put words on these panels. This is not a comic strip.”

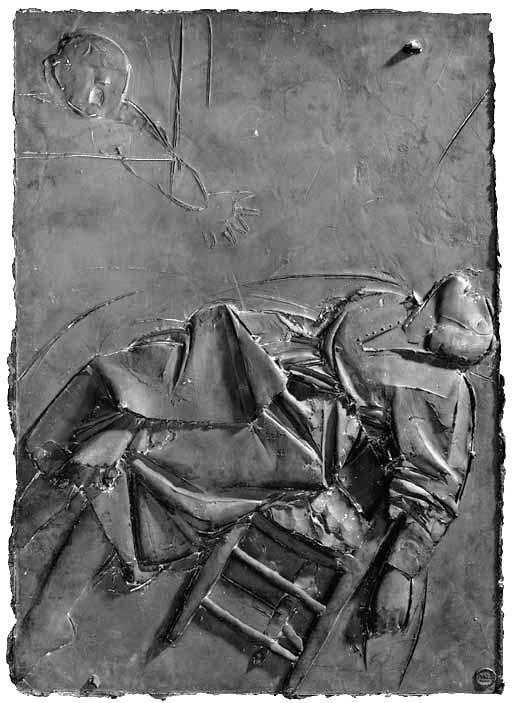

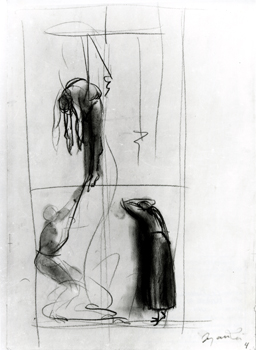

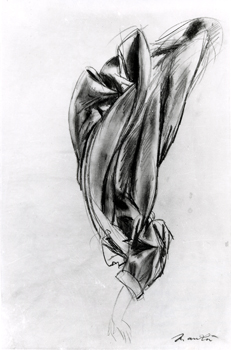

Perhaps the most emotionally devastating panel is Death on Earth, positioned at the lower right and serving as the final statement in this sequence on mortality. Here, a nameless, worn woman collapses against a tipping chair, while a child looks on in terror, crying as he witnesses his mother’s last moments. The restrained, tender modeling of the figures transforms the act of dying into something both intimate and inexorable, with the immanent pull of gravity as a result of the chair falling over conveying the immediacy of the loss.

The history of the door begins in 1947 when a competition to create a new set of doors for St. Peter’s Basilica was announced under Pope Pius XII, and the winner was chosen to be Giacomo Manzù, a sculptor from Bergamo, already known for his sculptures and bas-reliefs depicting cardinals and biblical scenes, culminating in an exhibition in Milan in 1941. While he was chosen for the work under Pope Pius, it was ultimately the next Pope and friend of many years, John XXIII, whose personal support allowed Manzù to transform what was meant to be a conventional celebration of saints and martyrs into a far more troubling meditation on mortality, violence, and human suffering.

Born in Bergamo in 1908, the son of a poor shoemaker, Manzù was largely self-taught. At age of 11, he took on a job assisting a local carpenter, going on to work on plaster decorations. It is said his first works of art were figures he modeled from leftover candle wax in the church where his father worked as a sacristan. His early fame came from austere sculptures of cardinals and emotionally restrained religious reliefs, but his work consistently mixed elements of the sacred, the erotic, and the political. Over a career of almost seventy years he produced busts of celebrities, female nudes, and monuments for institutions ranging from the United Nations to the Rockefeller Center, and even stage designs for Igor Stravinsky’s opera Oedipus Rex, created at the composer’s request.

From the beginning, Vatican officials were opposed to his insistence that the door should represent not heavenly glory but the earthly reality of death. The original title, The Triumph of Saints and Martyrs, was replaced, with John XXIII’s approval, by the stark and final theme of Death, following lengthy dialogues between the two men. Manzù interpreted it not only as a passage to divine reward but as an event marked by grief, injustice, and violence, insisting that sanctity could not be separated from history, and chose to depict it using classical sculptural traditions he was known for, but discarding the academic elements many would commonly expect to see when witnessing a work of art in the Church.

The project haunted Manzù for nearly seventeen years. He repeatedly abandoned it, rethought it, and nearly destroyed it in moments of crisis. During this long gestation he produced a parallel set of doors for the Salzburg Cathedral in Austria, effectively using them as a rehearsal for the Vatican work. The delays were not only artistic, Manzù was an atheist, openly sympathetic to socialism and communism, deeply suspicious of institutional authority, and widely regarded within the Curia as an ideologically inappropriate choice for so prominent a sacred commission. Following the death of Pope John XXIII, who in life urged Manzù to finish the work, he finally completed it a year later.

The door was inaugurated in 1964, a year after John XXIII’s death, during the very council he had summoned to renew the Church. Vatican resistance did not disappear, but the work could no longer be undone. Manzù, once considered disrespectful of the Church’s iconographic tradition and listed among the Holy Office’s “unworthy” artists (along with names such as Renato Guttuso) had permanently altered the visual language of Catholic monumental art.

The strained relationship with the Roman Curia, owing to Manzù’s beliefs may have lead to the work’s undoing had it not been for his friendship with the late Pope, who understood and appreciated his vision, following a meeting between them when Manzù was called to sculpt his likeness. This meeting proved to be crucial, where, despite their differing views, a lifelong mutual respect between the artist and pontiff was established, the latter who was also from Bergamo. Later, in a 1988 interview with La Stampa, Manzù states “They say I’m a Marxist. That’s not true. I’ve never even been a member of the Communist Party. But I feel like a communist in the sense that I desire a more fraternal and peaceful humanity. For me, being on the left is a more human choice than a political one.”

His reputation among members of the Church was not totally negative, and in time he found supporters in members of the clergy such as Dom Hélder Câmara, Brazilian Archbishop of Olinda and Recife, also known as the “Bishop of the Favelas,” who famously said: “When I feed the poor, they call me a saint, but when I ask why the poor have no food, they call me a Communist.” Years later, he was granted a commission to work on a third door, this time for the St. Laurens Church in Rotterdam, intended as a symbol of reconstruction following the destruction of WWII, another display of the artist’s lifelong commitment to peace.

Today the Door of Death is widely regarded as Manzù’s greatest achievement, a fusion of the secular and the religious. It does not console, instruct, or idealize. It insists that death is not abstract, not distant, and not purely spiritual, but human, political, and historical. In the world’s most powerful basilica, it stands as a rare acknowledgment that sanctity and suffering are inseparable, and that even in bronze, the Church cannot escape the gravity of the human condition. “I live for peace and have a ferocious hatred of war. Time proves me more and more right.” he stated in a 1977 inerview for Corriere della Sera.

Manzù, throughout his life, maintained a constant dialogue between the Church and communism and described his relationship with Pope John XXIII in these terms: “Our meeting point was charity, that is, what had to be done for men, for the fraternal coexistence of all in this world full of hate.”