New York–based artist Clement Valla has been steadily collecting images of the Earth, but not the Earth as we know it. Through his ongoing series, Postcards from Google Earth (2010–present), Valla has compiled a digital archive of topographic anomalies that defy the reality they are meant to represent: visual artifacts that expose the limitations of early machine learning and quietly anticipate today’s debates over the accuracy and authority of artificial intelligence.

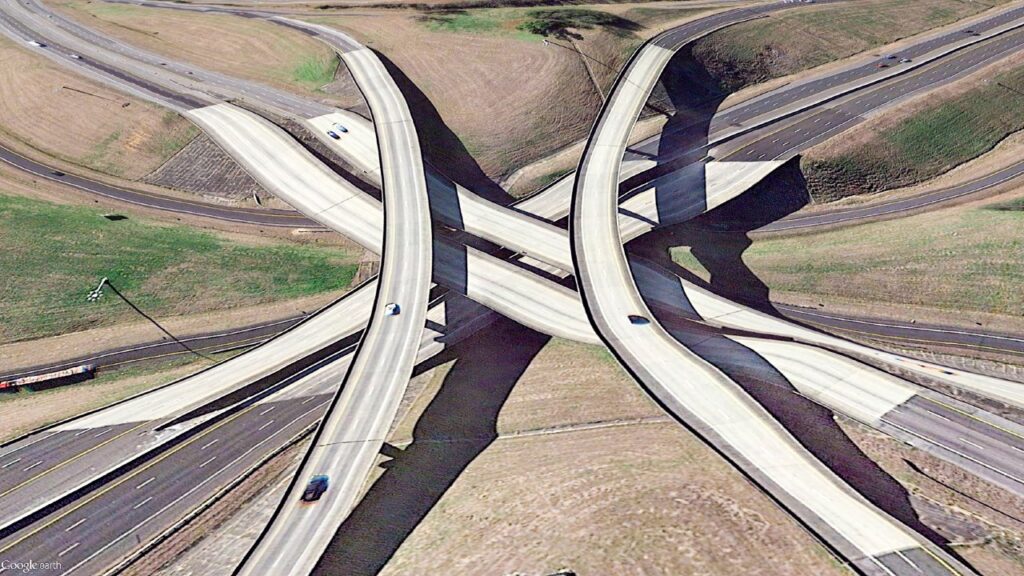

Bridges plunge at impossible angles into the water below, highway interchanges collapse into one another, and treelines stretch and warp into unnatural forms. For more than a decade and a half, Valla has gathered screenshots from locations around the world, primarily the United States and Switzerland, as Google Earth sees them, each image capturing a fleeting moment before the software inevitably receives new data, corrects itself, and restores the illusion of coherence.

The discovery was entirely accidental: “The first time I discovered this kind of error, I was stunned. I had commissioned paintings from Xiamen, China, for another art project. Out of curiosity, I searched for the city on Google Earth and saw an image of a bunch of buildings upside down or even completely distorted. … I started looking for other examples. I found the most spectacular ones near roads and bridges. That’s where the risk of incompatibility between the 3D model and the satellite photo is greatest. I would sometimes sit for hours in front of my screen following roads, knowing that I would eventually find a hilly section with a bizarre shape,” explains Valla.

In another interview, Valla explains the reason for this being due to “two competing visual inputs here—the 3D model and the mapping of the satellite photography—and they didn’t match up. The computer is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do, but the depth cues of the aerials, the perspective, the shadows, and the lighting were not aligning with the depth cues of the 3D Earth model. I figured that this was not a unique situation in Google Earth, and I started looking at obvious situations where the depth cues would be off—bridges, tall skyscrapers, canyons. Soon I noticed the photos being updated, and the aerial photographs would be ‘flatter’ (taken from less of an angle), or the shadows below bridges would be more muted. Google Earth is a constantly changing, dynamic system, so I had to capture these specific moments as still images.”

Google Earth infers height and form from shadows, camera angles, and photogrammetric data. When those cues misalign, particularly around bridges, elevated roads, steep canyons, and dense urban structures, the software “wraps” the image texture over the terrain mesh, producing grotesque distortions. Roads sag. Rivers appear to climb, flyovers melt into ravines, and suburban houses fuse with the trees behind them. The effect intensifies when man-made structures are excluded from the terrain model, leaving only natural topography beneath. The more oblique the source photograph and the deeper the underlying landscape, the more extreme the deformation.

The evolving nature of these maps echoes the evolution of paper cartography, where once-unknown territories were compiled from total hearsay and took on more accurate forms over the centuries as information became more readily available. Here, in a digital equivalent, we witness Google’s understanding of the Earth slowly converging toward something we can more easily recognize as our own, but until then, we are witnessing a surreal glimpse of what the world is thought to be, but not according to any human mind mind.

Because Google Earth’s landscapes are generated by artificial intelligence drawing from multiple aerial and satellite inputs, the project raises broader questions about how place is represented in the digital era. Other virtual worlds, particularly in video games, often recreate real locations at the expense of scale or accuracy, compressing cities and omitting unnecessary zones by design. But this simulacra is created so as a creative choice, both for the sake of flow and to cut down on development time, as these are products made by human hands. With Google Earth, however, “the software edits, re-assembles, processes and packages reality in order to form a very specific and useful model” and this creates inadvertent limitations in the representation of a given space.

Crucially, these images are temporary. As Google updates its datasets with flatter aerial photography, subdued shadows, and refined 3D models, the anomalies disappear. “Because Google Earth is constantly updating its algorithms and three-dimensional data, each specific moment could only be captured as a still image. I know Google is trying to fix some of these anomalies too. I’ve been contacted by a Google engineer who has come up with a clever fix for the problem of drooping roads and bridges. Though the change has yet to appear in the software, it’s only a matter of time,” Valla notes.

His practice is therefore as archival as it is aesthetic. Valla preserves a disappearing phase in the evolution of machine vision. In doing so, he is also creating an active chronicle of how the simulated world within is being shaped, arguably a concurrent timeline with our own real world, but one where landscapes shift and materialize much more drastically than the ones in our reality. In addition, this allows us, as Valla sees it, “focus our attention on the network of algorithms, computers, storage systems, automated cameras, maps, pilots, engineers, photographers, surveyors and map-makers that generate them”

In an essay for Rhizome, Valla discusses Google’s “Universal Texture,” a proprietary system that maps an immense, continuously updated photographic collage onto a three-dimensional model of the globe. “The Universal Texture promises a god-like (or drone-like) uninterrupted navigation of our planet—not a tiled series of discrete maps, but a flowing and fluid experience.” This aspiration mirrors the expansive claims made by contemporary technology companies, such as OpenAI, suggesting a form of planetary knowledge and interconnectedness that is total, seamless, and consumable, with one commentator suggesting this presentation reframes the earth as itself a product to be consumed.

Valla further compares this seamlessness to the invention of the escalator: “No invention has had the importance for and impact on shopping as the escalator… the escalator accommodates and combines any flow, efficiently creates fluid transitions between one level and another, and even blurs the distinction between separate levels and individual spaces.” To Valla, akin to the infinite scroll of social media (what we would now call the doomscroll), there is no start or finish to the escalator, and subsequently there is no start or finish to the flow of information, and no distinction of where it comes from, be it the public, Google’s employees, or government agencies. Instead, there is an interminable flow of data points and a program creating an image using only the best ones. It delivers what would seem to be the ultimate perspective: frictionless, omnipresent, and always in daylight.

How Google determines which images are “best” remains opaque. Angle, season, and lighting all play a role. There is, notably, no night in Google Earth. Clouds are systematically removed. High-contrast, clear-weather imagery is favored. The outcome is a world optimized for legibility rather than fidelity, a statistically curated Earth that suppresses atmospheric noise, temporal disruption, and visual ambiguity.

A great essay addresses this fact, stating that roughly every part of the world you see is from a photo taken during the day and in springtime. The essay goes on to underline the importance of “smoothness” as a factor, i.e. images which lack elements that may play a role in creating a flawed model, such as clouds, smoke, or various disasters, yet this often means that many unfortunate realities are ignored or “airbrushed” from the record, one notable example is in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, when Google opted to use pre-hurricane photos of the southeastern US. In erasing these realities, the world is still imperfect, only this world’s imperfections are due to a lack of perfectly accurate data for the program to properly process, with the implied expectation that eventually these imperfections will be totally done away with, a promise that could not be reasonably made for the real world we occupy.

Seen from the vantage point of more than fifteen years since its inception, Valla’s project anticipates contemporary anxieties surrounding AI’s role in culture and knowledge production, facets of our lives commonly associated with the human touch. Where paper maps were compiled by hand, and the best routes and landmarks were often left to the suggestions of locals or those with lived experience of a given area, this now comes as one of the first elements of the human experience to fall to AI, long before any concerns that art could be taken over as well.

The images are not manipulated. There is no compositing, no retouching. Their aesthetic emerges entirely from automated processes—“atypical ephemera” produced by advanced systems at planetary scale. As Valla observes, “There is very little direct human hand in these artifacts… it’s about framing them, allowing them to be seen, and revealing a strange byproduct of these super-functioning systems.” In time, these distorted landscapes may be remembered much like the mythical continents and phantom islands of early cartography.

By calling them “postcards,” Valla also gestures toward a form of armchair tourism: a world apprehended remotely, through a polished and minimal interface, engaged and understood through the comfort of one’s own home, echoing the manifestations of optimistic globalization from the 90s such as the world music boom and the Soft Colonial Wanderlust aesthetic, only this time presented in a streamlined, minimal image of the earth as it is (or as it could be).

“Satellite photos aren’t made to be beautiful,” Valla notes, “They are beautiful by accident.” His act of archiving and highlighting utilitarian cartographic data transforms it into something contemplative and uncanny, closer to surreal landscape painting than to technical imaging. In this sense, Postcards from Google Earth belongs to a broader tradition of glitch art and critical media practice, alongside artists who interrogate how software shapes perception: Trevor Paglen’s surveillance imagery, Hito Steyerl’s essay on the “poor image,” or Mishka Henner’s use of Google Street View. Yet Valla’s contribution is distinct in its quietness. These images are not spectacular failures, but subtle ruptures in a system designed to hide its own mechanics.

Google has acknowledged the project, and at times even responded. The engineer that contacted Valla also sought permission to use his images in an internal company presentation to help solve the very problems the artist has attempted to document. In another interview, he states that Google’s only official response was their request that he retain the logo and copyright information in his screenshots. While the company has worked to remedy the surrealist landscapes, notably in high-interest locations such as the Golden Gate Bridge and the Hoover Dam, more remote areas often retain their warped geometry to this day, despite new satellite images having been overlaid onto them in the intervening years.

Despite what the viewer may believe, Valla maintains the old adage that the purpose of a system is what it does and that the images we are seeing are not glitches, for a glitch would imply that the program is not running the way it should. “They are the absolute logical result of the system. They are an edge condition—an anomaly within the system, a nonstandard, an outlier, even, but not an error.” In the end, Postcards from Google Earth is less about error than about exposure. It makes visible the hidden infrastructure of contemporary vision: algorithms, sensors, pilots, surveyors, servers, and software, all collaborating to produce the illusion of a single, stable, knowable Earth.

And in those rare moments when the illusion fractures, we are offered something that seems more like a sobering reminder of our own time rather than a strange novelty, that many of the new technologies we engage with on a near-daily basis, despite drawing from seemingly limitless resources and information, are not omnipotent and certainly not perfect, even if they are running exactly as they were programmed.