For more than fifty years, the Texas Prison Rodeo turned incarceration into public entertainment, drawing massive crowds to Huntsville to watch men serving long sentences risk their lives for cash, awards, and a fleeting sense of glory.

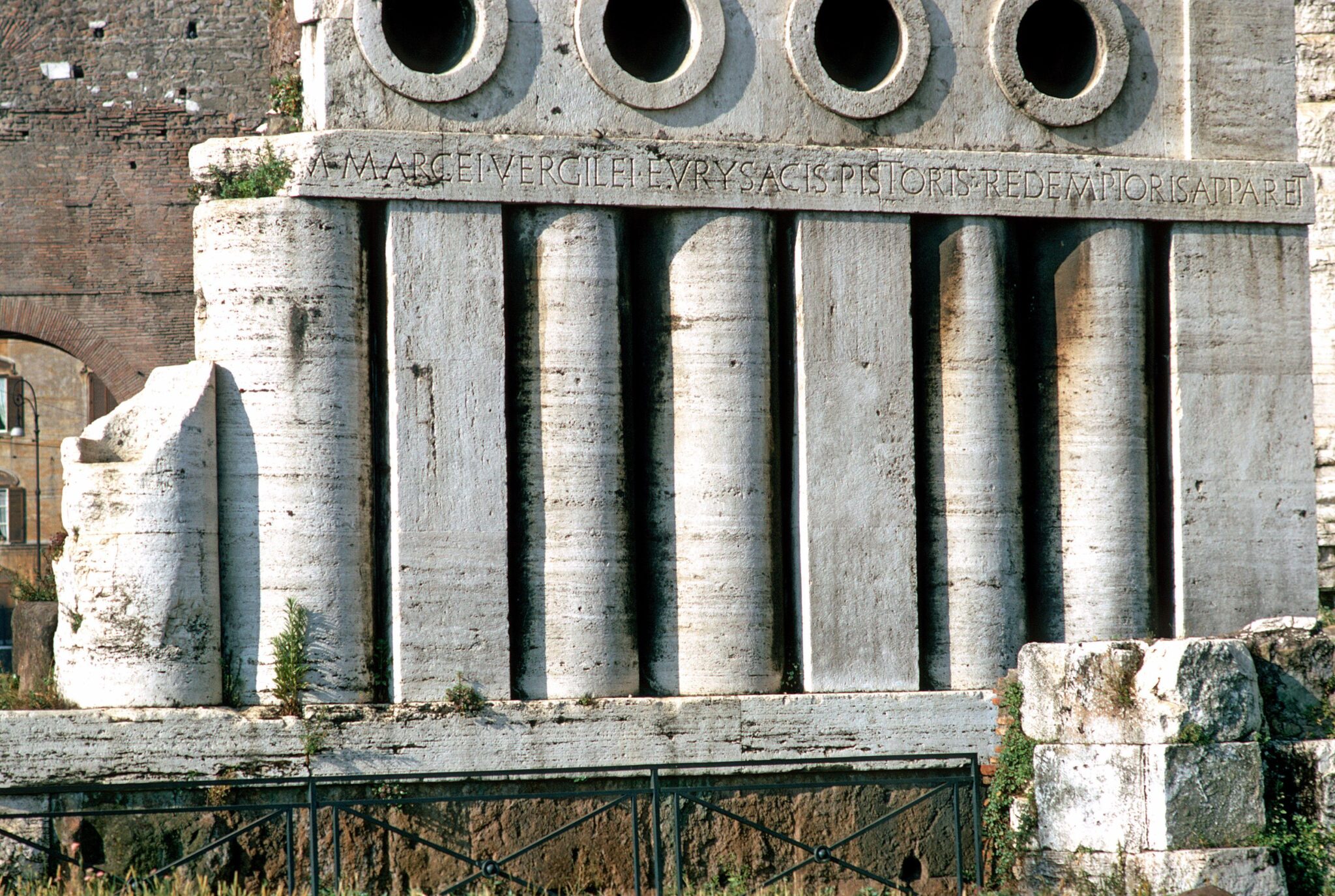

Fittingly enough, the first inmate ever brought to Huntsville in 1849 was a convicted horse thief. Nearly a century later, that small historical irony would metastasize into one of the strangest, most popular, and most morally ambiguous spectacles in American sports history: the Texas Prison Rodeo.

In the decades leading up to the 1930s, conditions across the Texas prison system, now known as the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, were brutal. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Jim Crow laws disproportionately targeted black Texans, swelling prison populations that were then leased out to private companies for forced labor. As public criticism of convict leasing intensified, the state shifted toward prison-owned farms, operations remote enough to continue largely beyond public scrutiny. It was here where the idea took form.

The rodeo began in 1931 at the Texas State Penitentiary in Huntsville, the town dominated by the red-brick prison complex known simply as The Walls. Conceived by Lee Simmons, the Texas prison system’s general manager, the event was pitched as internal entertainment purely for inmates and prison employees during the depths of the Great Depression, using equipment and skills already available to the convicts working the prison-owned farms.

After securing the blessing of local clergy to hold the rodeo on Sunday afternoons in October, Simmons trucked in livestock, inmates, and spectators from outlying prison farms and staged the first event on a converted baseball field behind the prison, creating a rare moment of camraderie between the watchers and the watched.

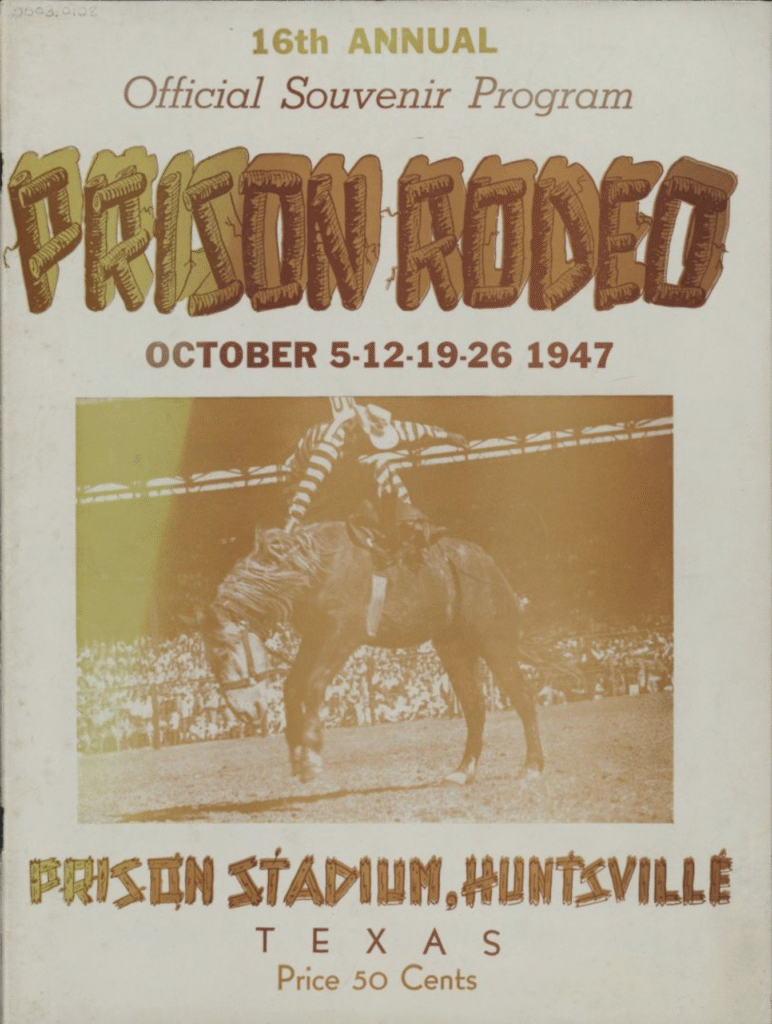

From the start, the response exceeded expectations. What began as a diversion quickly became a phenomenon with locals in attendance. Within two years, the numbers of visitors had swelled to nearly 15,000, prompting officials to erect wooden stands and begin charging admission. The revenue covered costs and funded the inmates’ Education and Recreation Fund, which paid for everything from textbooks and dentures to prosthetic limbs, prison chaplains, and Christmas turkeys, expenses the Texas Legislature refused to cover.

Advertised as “the wildest show behind bars” or even “the wildest show on earth,” the rodeo grew into a must-see spectacle in a town of just 38,000 people. By the late 1930s, seating had doubled. A 1940 TIME dispatch reported that 2,000 to 3,000 people were turned away on a single Sunday while 25,000 others gladly paid the 50 cent entry fee. In response, a $1 million red-brick arena with a capacity of 20,000 was constructed by the inmates themselves in 1950, intended to visually compliment the prison itself. At its height, the Texas Prison Rodeo drew as many as 100,000 spectators annually, making it the largest sporting event in the state.

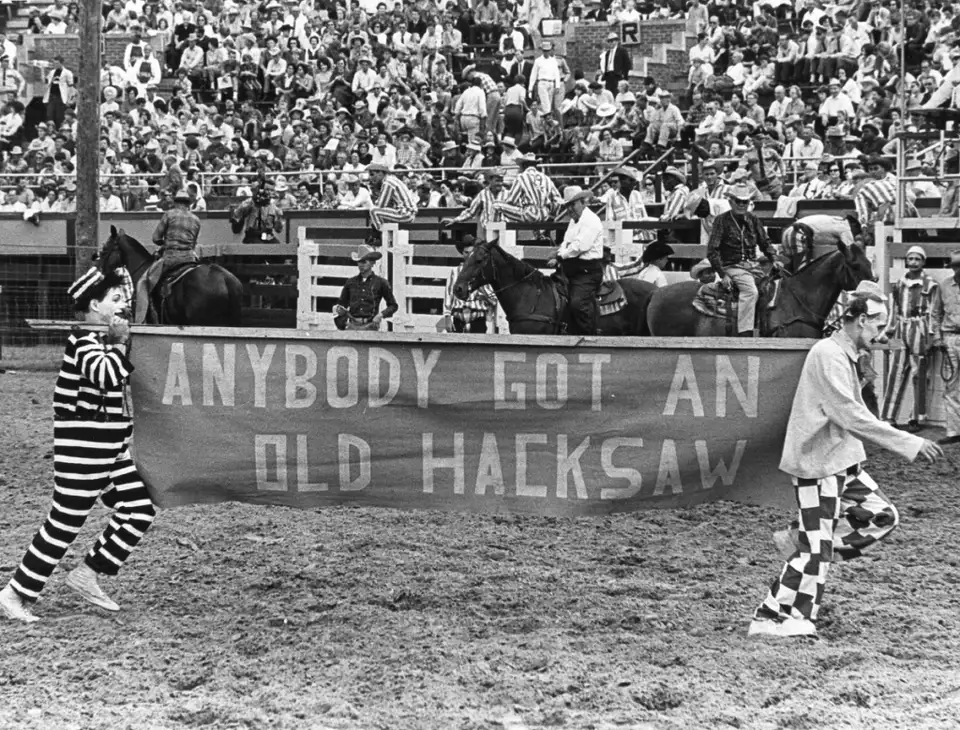

From the beginning, spectacle was the point. Inmates opened each rodeo with a parade through the arena, including rodeo clowns carrying handmade jokey signs reading “Take a Convict Home With You” and “Anyone Got an Old Hacksaw?” while inmates rode in on horses, carrying American and Texan flags.

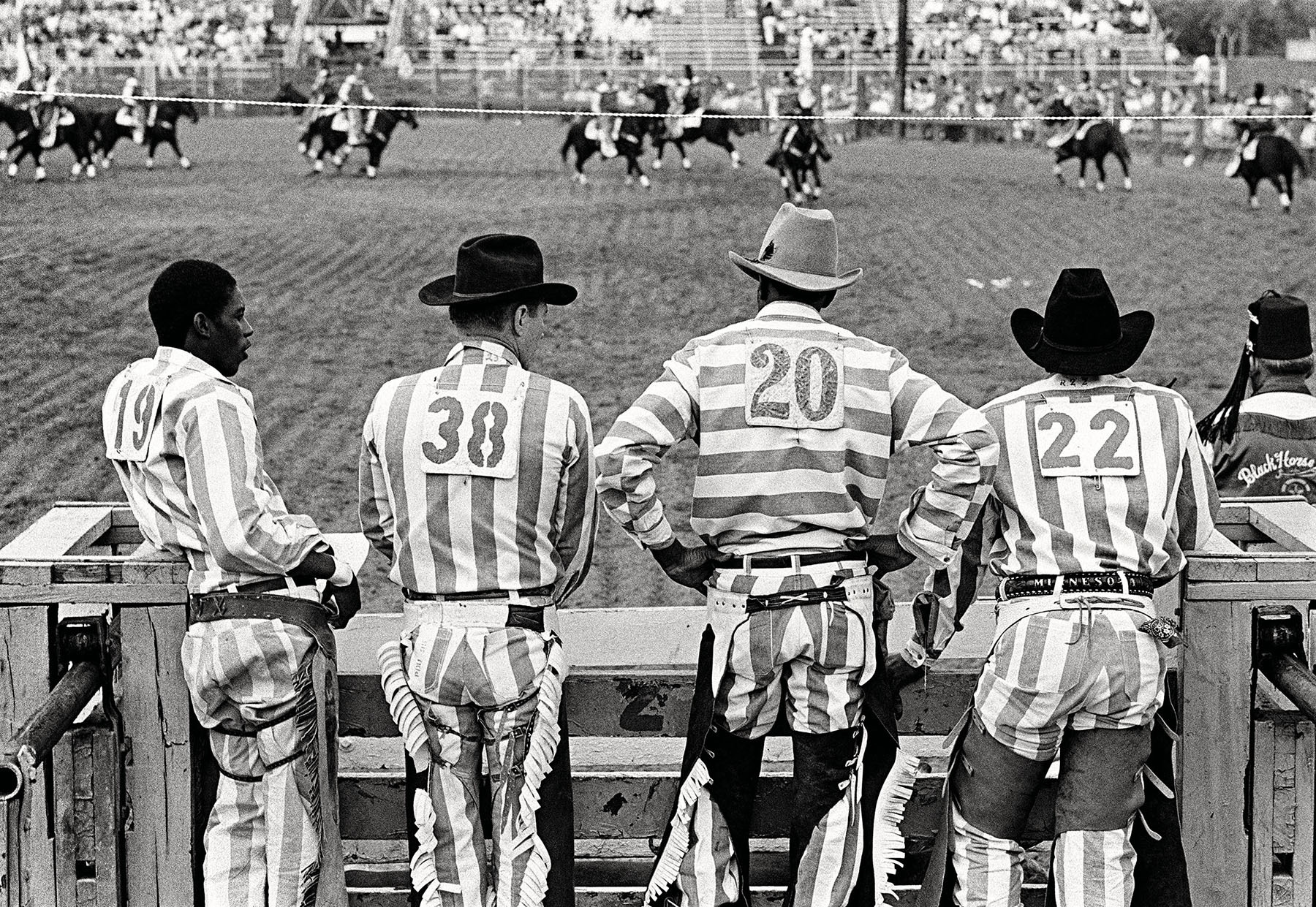

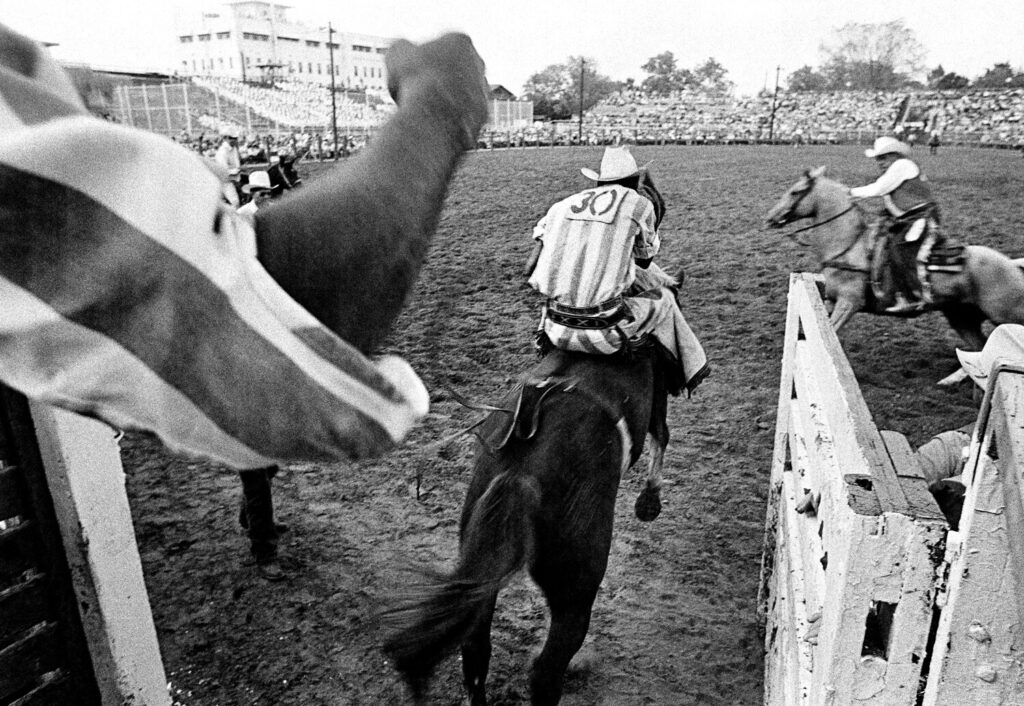

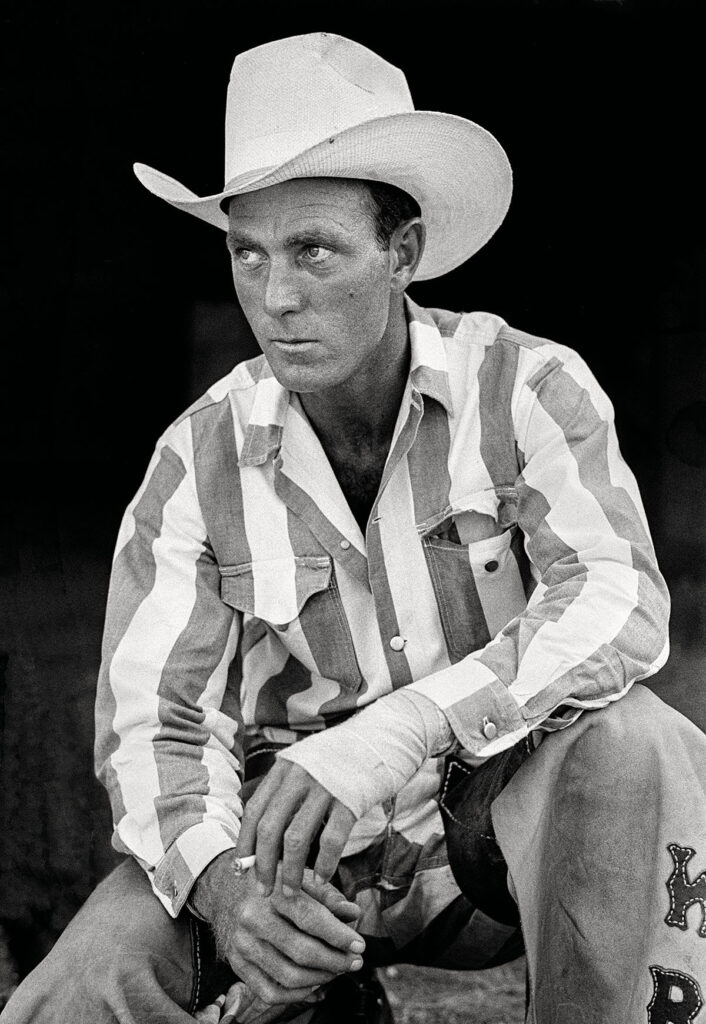

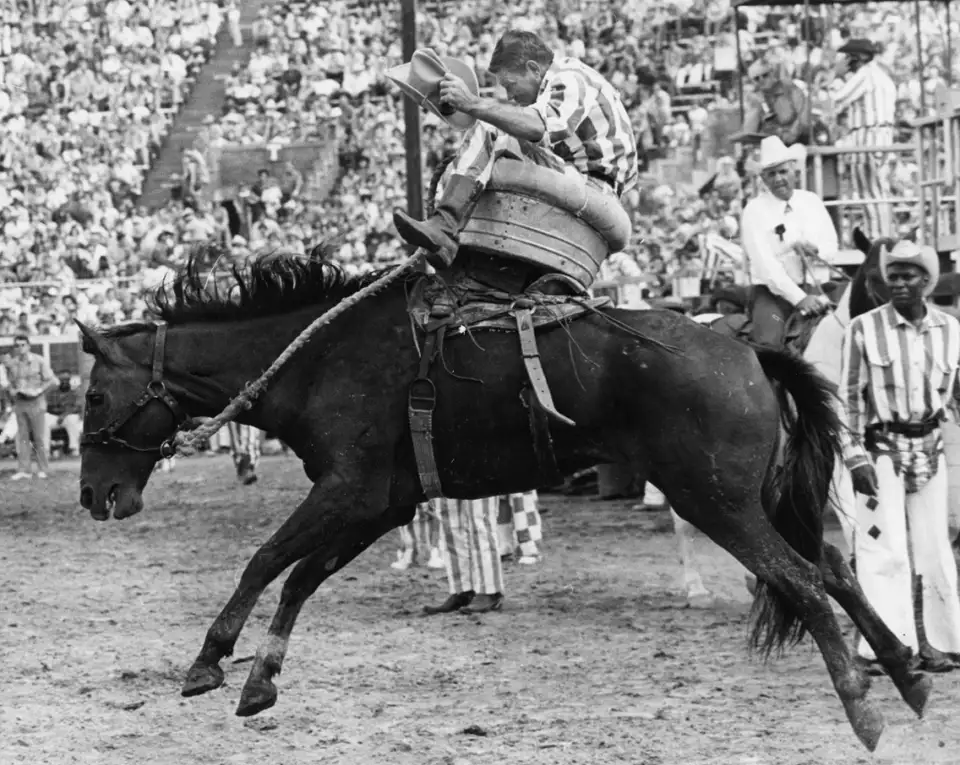

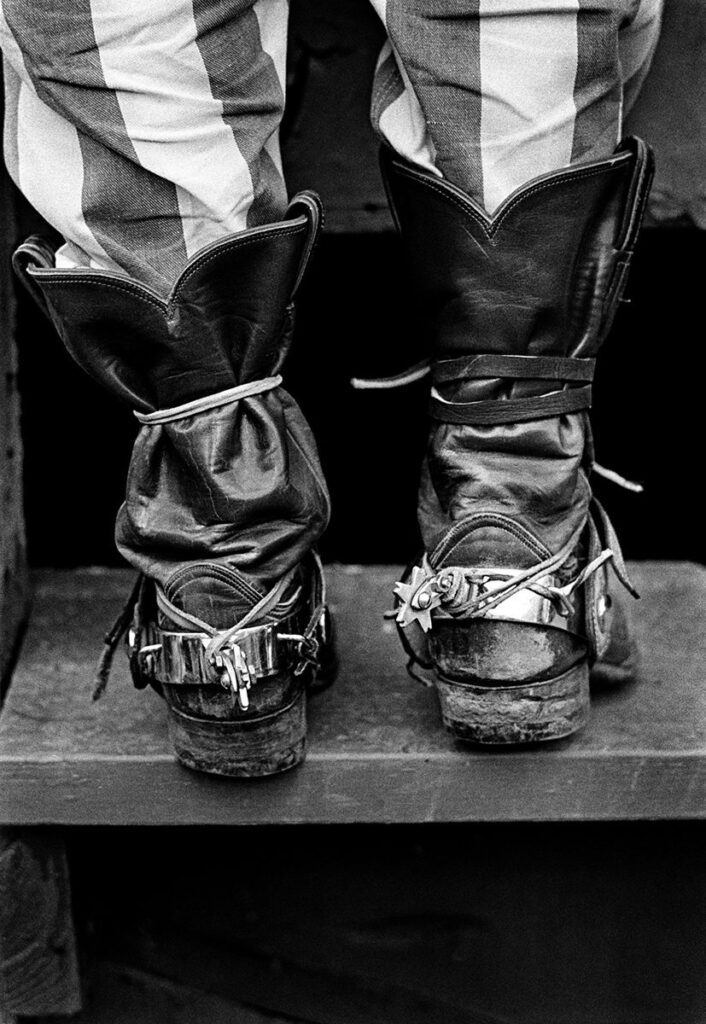

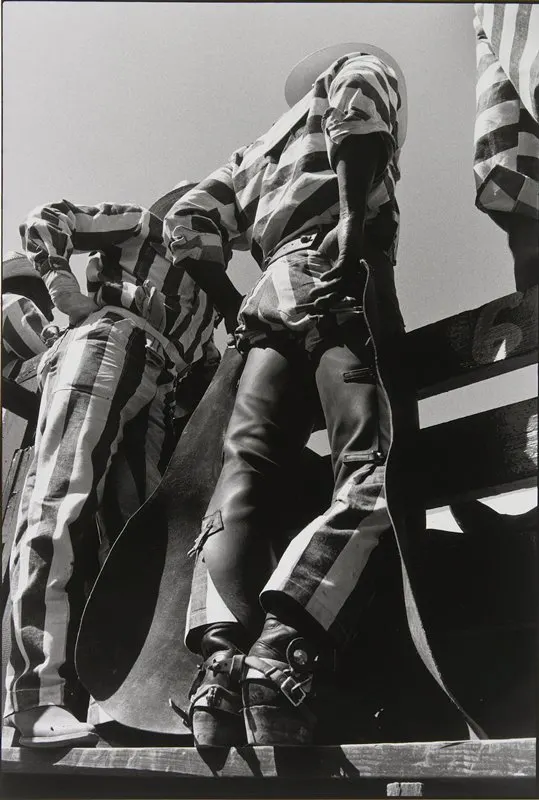

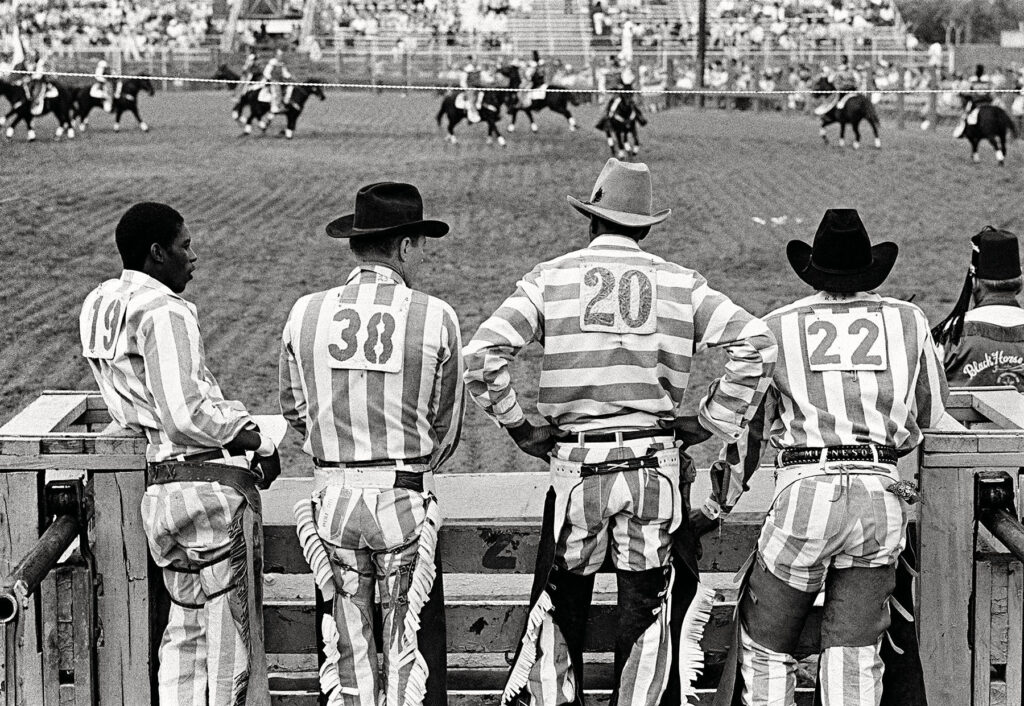

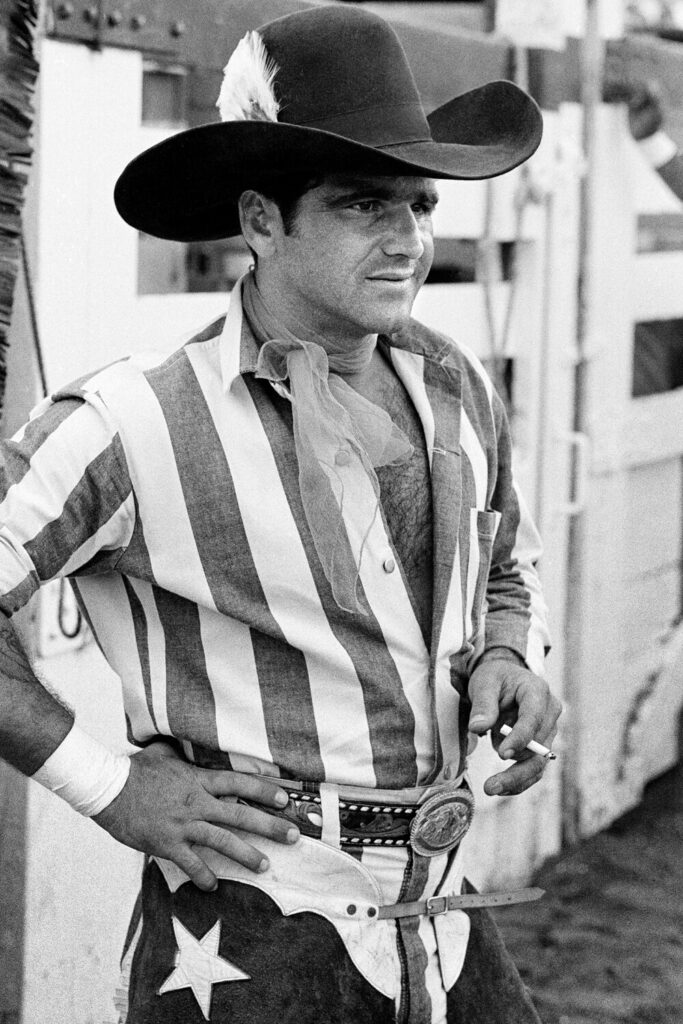

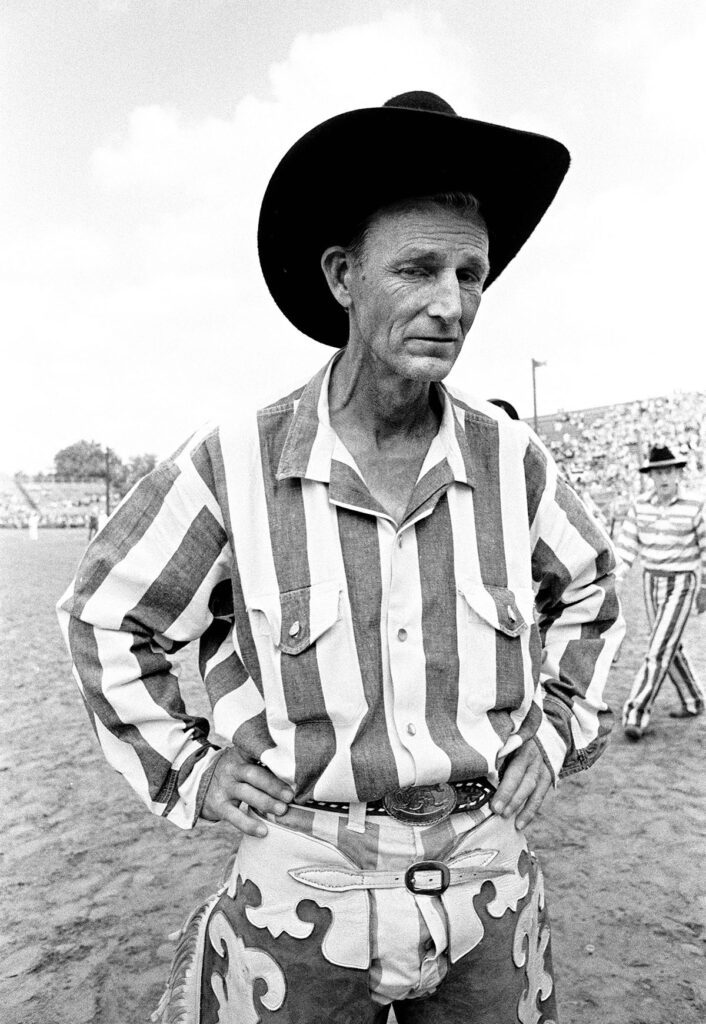

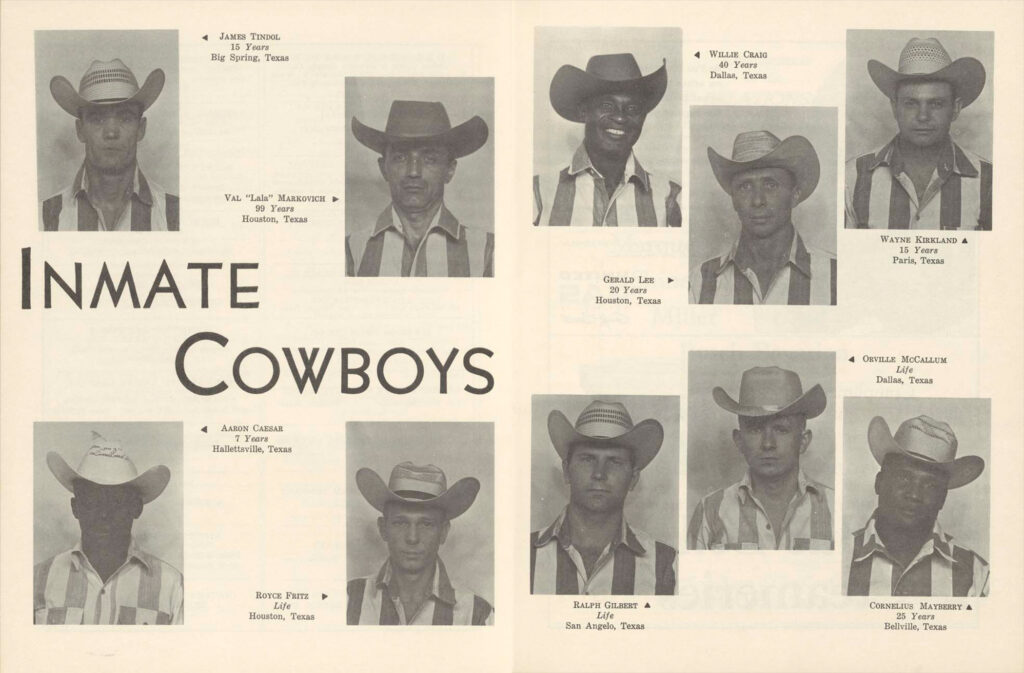

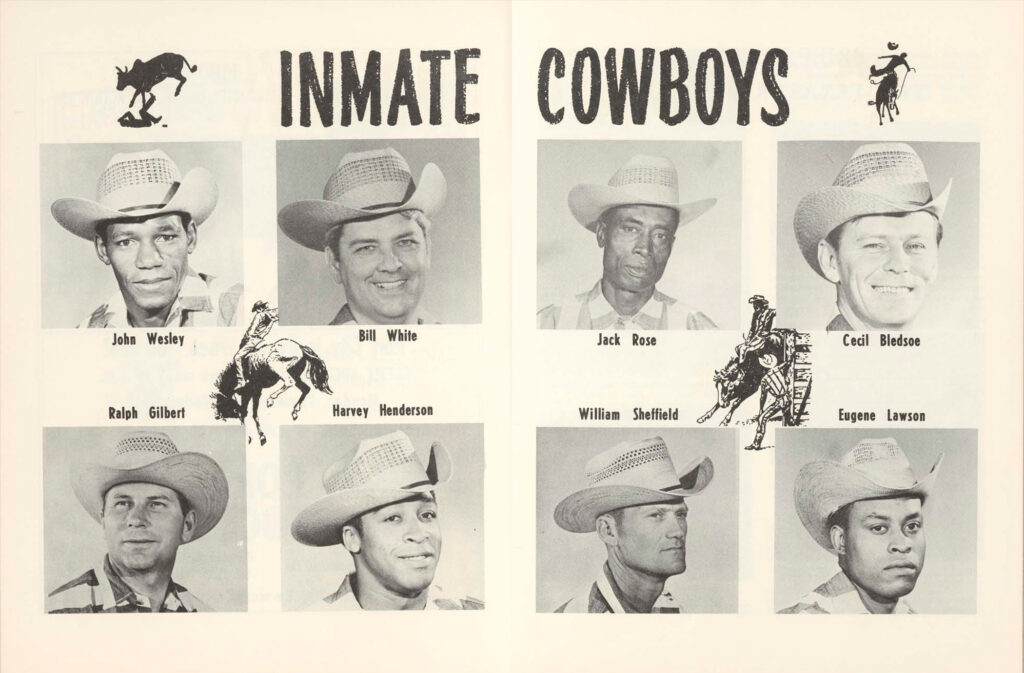

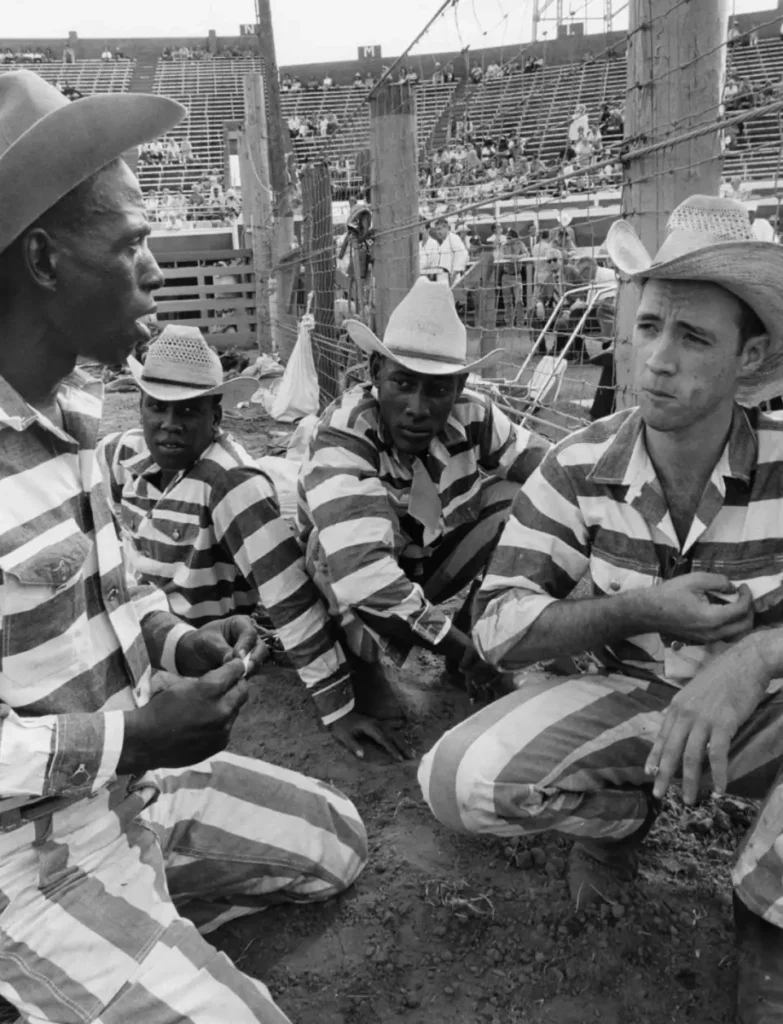

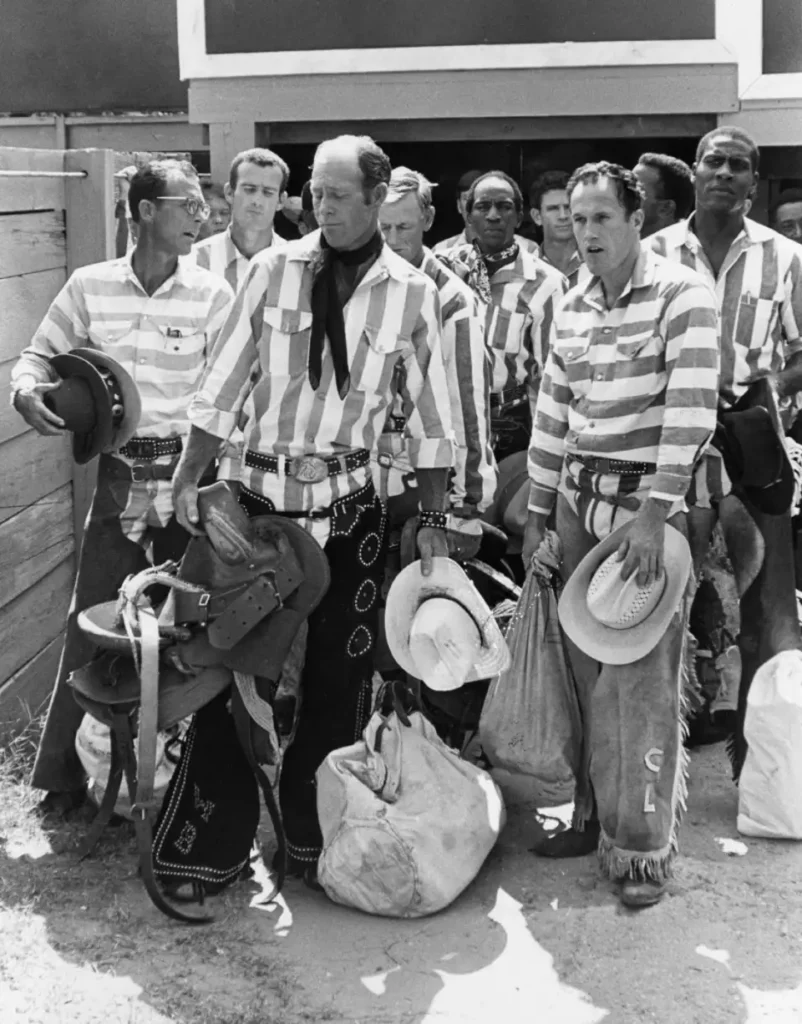

Participation was initially limited to experienced ranch hands, but by the 1940s, according to the Handbook of Texas, “any male inmate with guts and a clean record for the year could compete at open tryouts in September for one of 100 or so rodeo slots.” By 1937, inmates were wearing the now-iconic zebra-striped uniforms, not the standard white prison garb worn inside the prison walls, but costumes demanded by public expectation. Stripes, after all, sold tickets and sold the idea these were bona fide convicts.

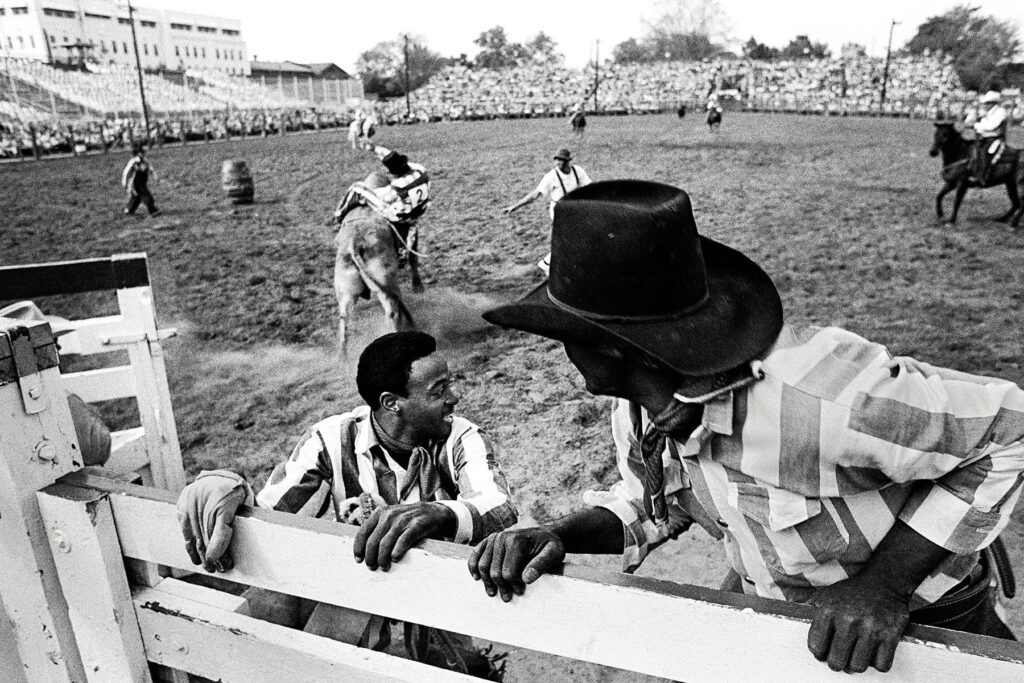

The rodeo unfolded during Jim Crow, yet it was likely the first desegregated sporting event in the state of Texas, if not the entire South. Black and white inmates competed together in the same arena, even as spectators remained segregated in the stands, many of them having come from other counties just to see the rare sight of black rodeo performers.

“This wasn’t just a chance to watch a rodeo,” says Mitchel P. Roth, professor at Sam Houston State University and author of Convict Cowboys. “This was a chance to watch the convicts. It was a glimpse inside a prison. This was a world people didn’t have access to.”

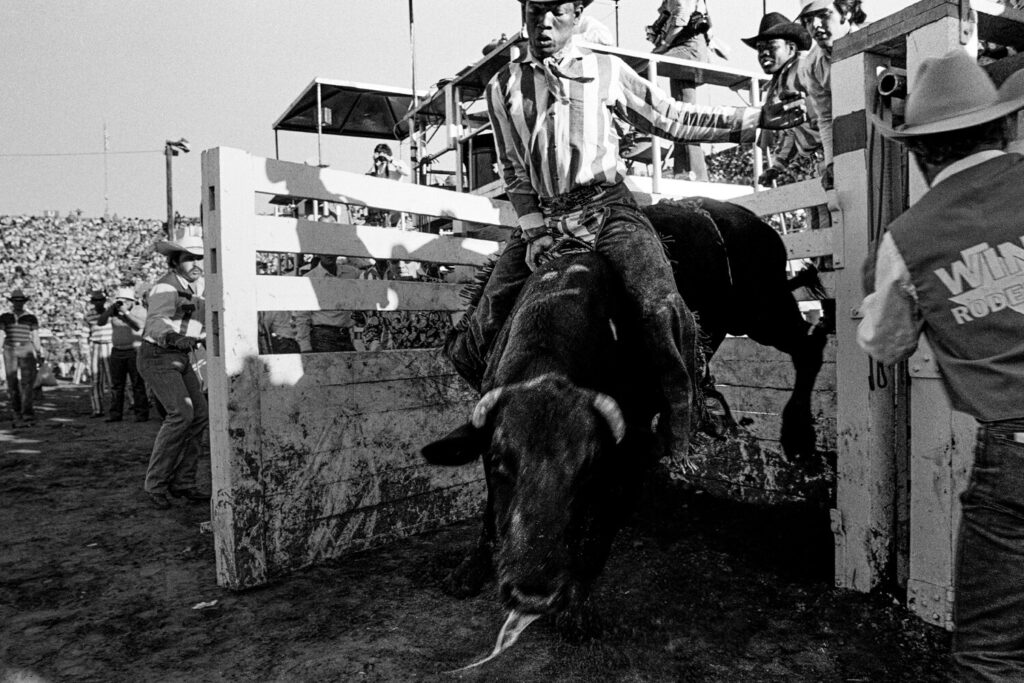

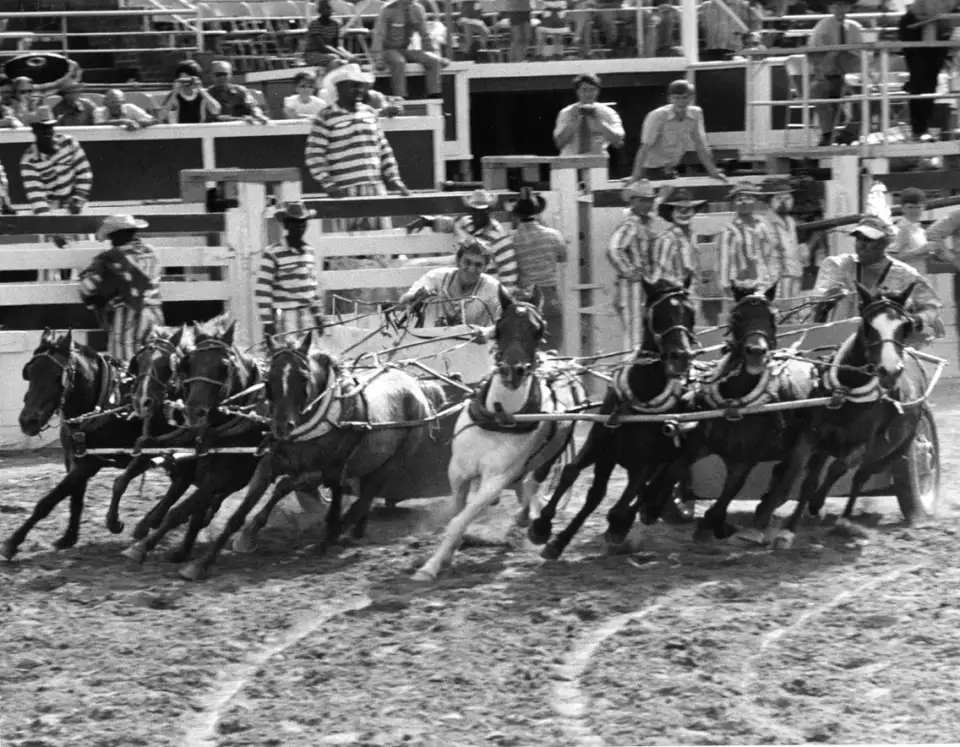

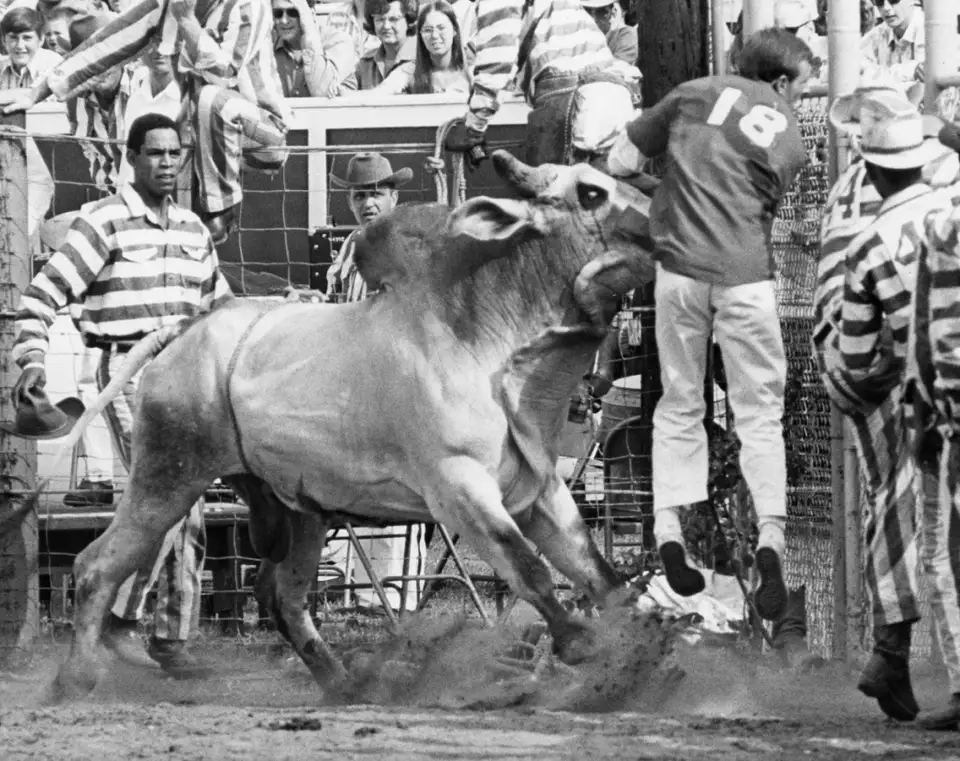

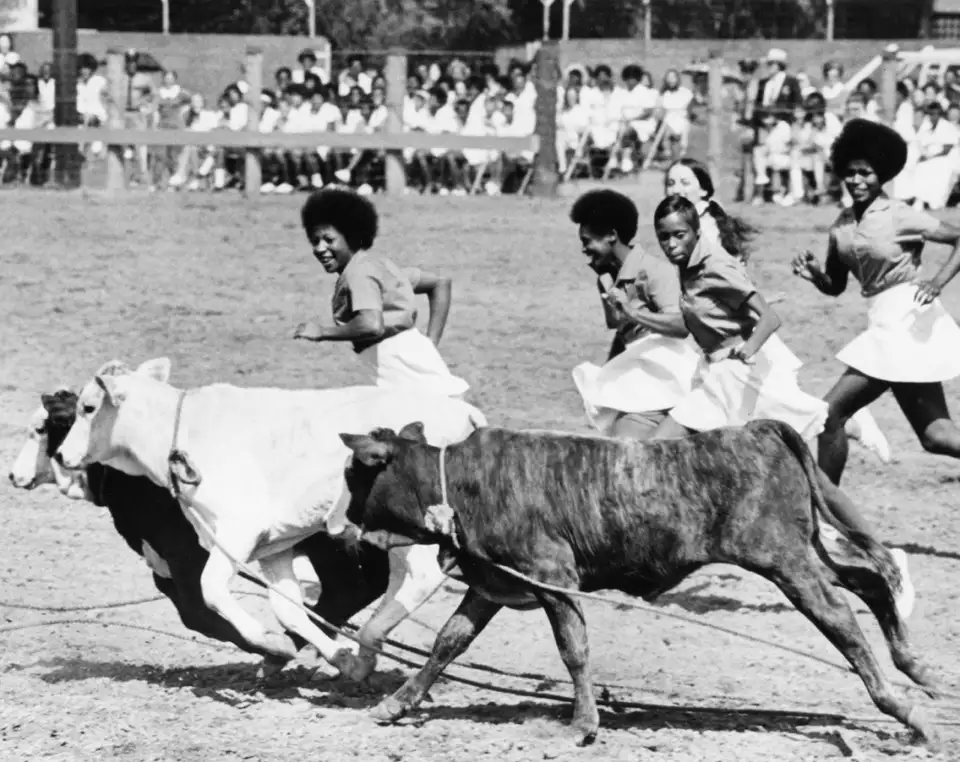

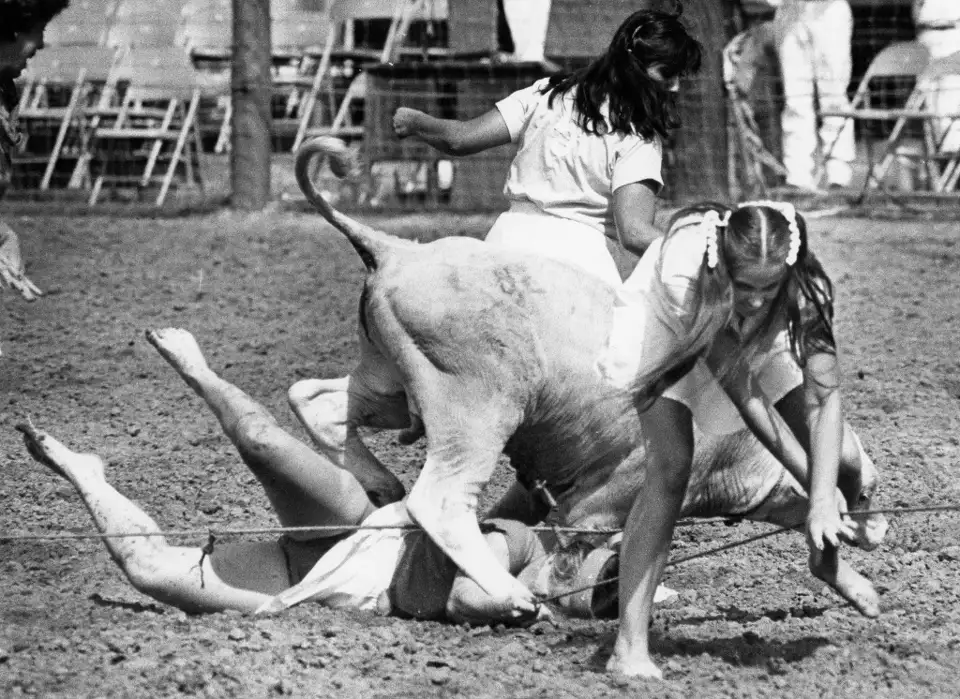

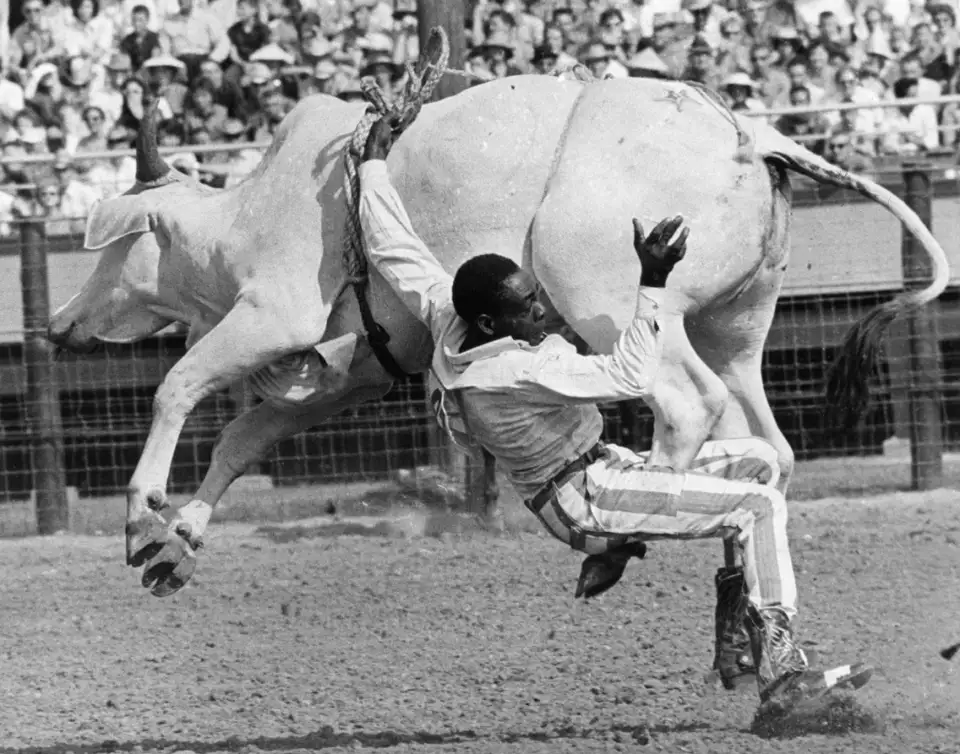

The events were both standard and bizarre: bull and bronc riding alongside chariot and stagecoach races, mule races, goat roping, wild mare and cow milking, and the infamous Mad Scramble, where ten surly Brahman cattle charged into the arena simultaneously, bucking and colliding as inmates raced them across the dirt. The last remaining contestant who reached the other end of the field would be declared the winner. Too dangerous for most professional rodeos, the Mad Scramble was a crowd favorite.

The latter was one of the so-called “redshirt” events, dangerous stunts designed for maximum participation and carnage. The most notorious was Hard Money, in which inmates attempted to snatch a tobacco sack from between the horns of a bull. The sack usually held at least $50, often $100, and in some years ballooned to $1,500 thanks to donations from the crowd. “Things got a little intense then,” recalled Jim Willett, a former warden and now director of the Texas Prison Museum “There were guys who weren’t all that brave for $100, but they’d get pretty brave for $1,000.”

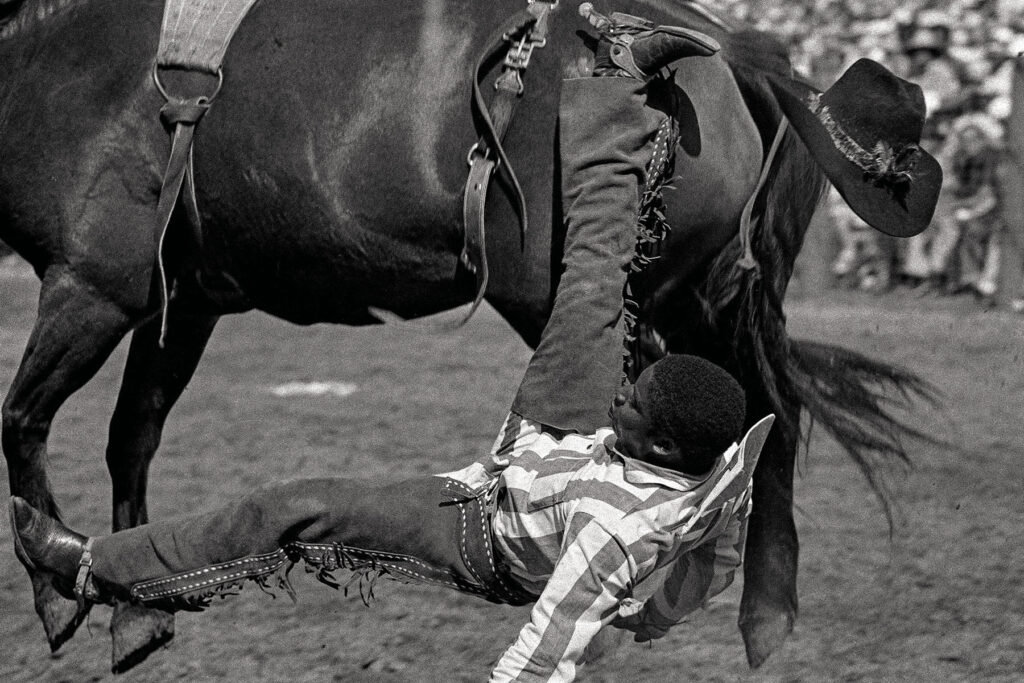

Inmates signed liability waivers absolving the prison system of responsibility for injuries, which ranged from broken limbs, ribs, and necks to severe wounds and contusions. Two inmates died over the rodeo’s long run, including H. P. Rich, a man serving only a four-year sentence, dying after being thrown from a steer.

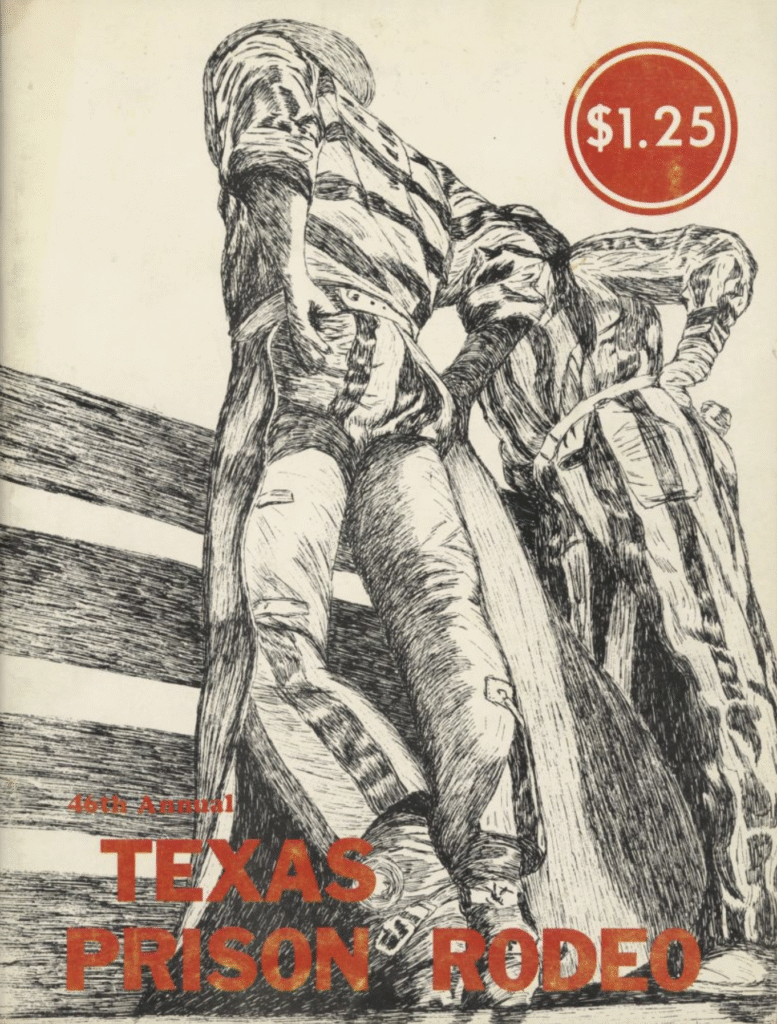

The logistics of the rodeo drew in the entire prison system and much of the surrounding community. Farm inmates rounded up wild steers from river-bottom pastures, while female inmates at the Goree Unit sewed the cowboys’ distinctive zebra-striped uniforms. Inside The Walls, inmate printers and journalists produced souvenir programs, often laced with self-deprecating satirical cartoons about prison life, and prison leatherworkers tooled saddles and chaps for riders whose families couldn’t supply their own gear. Despite this long-standing involvement, it wasn’t until 1972 that female inmates were allowed to compete in the arena themselves, when women from the Goree Unit were finally permitted to try out for typically female rodeo events such as calf roping, barrel racing, and greased-pig sacking.

Taking advantage of the brief moment amongst the public, inmates often interacted with people from the outside, if only briefly and at a distance. During those Sunday afternoons, competitors would try to acknowledge family members and lovers in the stands, sometimes only with a glance or a gesture. Officially, they were forbidden from speaking to spectators, but the rules were often bent. In one instance, a rider mouthed I love you toward someone in the crowd. When asked by journalist Greg Lyons if he had been taking a risk, he didn’t hesitate: “Damn straight,” he said, pointing. “My wife and kids was back up here and my girl was over there and didn’t neither of ’em know about the other.”

Families on the outside often supplied the gear riders needed to compete: saddles, chaps, gloves, while other inmates, more often women, refused visits altogether, fearing the spectacle of womens events were demeaning and would permanently warp how they were seen by loved ones. As Lyons further notes, many participants weren’t seasoned cowboys at all but urban men with little interest in ranch life; over time, the rodeo shifted from skilled farmhands to untrained, reckless novices, driven less by tradition than by the promise of status among fellow inmates and, above all, money. However, older performers still tried to impart their knowledge to newcomers, creating a transfer of skill that sometimes proved useful to those who might one day be released back to the outside world.

Naturally, inmates took advantage of the event and the bent the rules in other ways as well. In one documented instance, two inmates managed to escape by slipping under the stands and changing into civilian clothes left by an accomplice. Shortly after getting changed, they were spotted by a guard, only to be promptly escorted and thrown out of the event, under the belief the inmates were spectators that snuck in without paying.

For those that participated, the money mattered. In 1933, a winning inmate could earn $2, about $50 today, which amounted to extra money for commissary purchases. More importantly, the rodeo funded medical care and necessities prisoners would otherwise have to pay for themselves. “If they needed new dentures or a prosthetic limb, they’d have to come up with the money on their own,” Roth explains.

The rodeo was also a major entertainment venue. Over the decades it featured George Jones, Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, Dolly Parton, Ernest Tubb, Wanda Jackson, Waylon Jennings, Bo Diddley, Ray Price, and George Strait, among others. Actors John Wayne, Steve McQueen, and more were invited onstage as well. Prison bands like the Huntsville Prison Band and the Goree Girls String Band were regulars. The Goree Girls, formed in 1940, were among the first all-female country bands in America and regularly broadcast live from Huntsville on the radio, even being allowed to tour the country, performing at various rodeos while continuing to serve their sentences.

Johnny Cash, only a few years into his career, played his first-ever concert at the Texas Prison Rodeo in the late 50s, earning $2,000 (roughly $24,000 today), returning to the stage in subsequent years. Cash later credited the rodeo with launching his prison concert circuit, nearly a decade before his performance at Folsom Prison.

Candy Barr, born Juanita Dale Slusher, became one of the rodeo’s most notorious figures. A burlesque dancer turned celebrity inmate at the Goree Unit after previously making headlines for shooting her allegedly abusive husband (the charges were later dropped) and a possession of marijuana charge the following year, she joined the Goree Girls and later returned as a non-inmate performer, singing at five rodeo shows in 1966. In the 1960s, she was also connected to Jack Ruby, the Dallas club owner who murdered Lee Harvey Oswald.

In 1947, former inmate Bert Stonehocker became the first ex-prisoner allowed to return as a free-world entertainer, reprising his popular role as rodeo clown. The rodeo was no stranger to grander spectacle, either: one year, officials discovered an inmate was a former paratrooper and arranged for him to parachute into the arena. On a practice jump, he landed on a house roof and terrified the occupants, on subsequent performances during the rodeo, he missed the target during every time.

However, no figure embodied the contradictions of the Texas Prison Rodeo more than O’Neal Browning. Born around 1931, the same year Simmons began planning the rodeo, Browning was a gifted black cowboy who began riding bulls at sixteen while working the Houston Fat Stock Show and Rodeo. His father objected violently to his rodeo ambitions, beating him even after he began winning prize money.

In a drunken rage, Browning killed his father with an ax and was sentenced to life in prison. He joined the Texas Prison Rodeo in 1950, winning the coveted Top Hand Title in his first year at just nineteen, a prize silver belt buckle awarded to the competitor who earned the most prize money over the four Sundays of the rodeo.

Over three decades, Browning won the Top Hand buckle seven times, an unprecedented record, and became the only inmate to win the title in three separate decades. By the 1970s, he was still competing despite having only one thumb, the result of his left thumb being caught in a rope loop. “When the steer jerked, it pulled it completely off,” Browning later explained.

Every member of the rodeo had a rough past, and the audience was aware of this fact, which increased the appeal of such an event. One report describes several of the participants: “Martin Tuley used a pistol to hijack a gas station when he was 18. Joe Torres committed robbery by assault at 25 and has been locked up since 1967. Fred Burke was convicted of killing his wife ten years ago. Gary Hart was convicted of trying to rape a police lieutenant’s wife. These four men have two things in common: they are all inmates in the Texas Department of Corrections, serving 199 years between them, and they are all rodeo clowns.”

By the mid-1970s, the rodeo was clearing at least $200,000 annually. For a brief period, the Texas Prison Rodeo even intersected with space program history. During training for the 1975 Apollo–Soyuz mission, NASA brought Soviet cosmonauts to Huntsville to witness the spectacle. It was part business, part public relations, and part voyeurism.

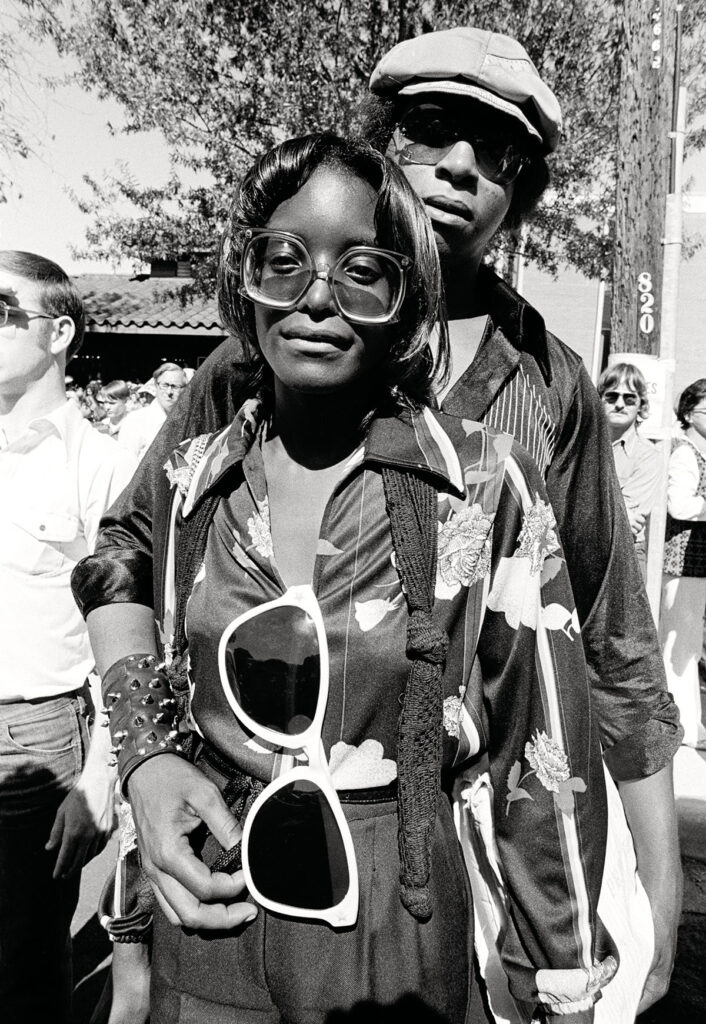

Visitors browsed paintings and drawings made by convicts for sale, bought novelty wanted posters with their own faces printed on them, and treated themselves to snacks while people serving life sentences were risking their lives for sport just a few feet away.

The threat of real danger, of injury, chaos, even bloodshed, wasn’t incidental to the rodeo’s appeal, it was central to it. Spectators increasingly gravitated toward events engineered for maximum risk, where unpredictability outweighed skill. Single-animal rides gave way to mass releases of bulls and cattle, multiplying the chances of collisions, falls, and disaster. The logic was simply that the higher the likelihood of violence, the larger and louder the crowd became.

Beyond the prison walls, black cowboys in particular had long faced exclusion from the mainstream world of professional rodeo. Larry Callies, founder of the Black Cowboy Museum in Rosenberg, recalled watching black riders barred from competitions, denied entry altogether, or penalized by biased judging. In contrast, the prison rodeo’s racially integrated arena led some contemporary publications to frame it as a rare space of opportunity for black inmates.

Callies disagreed. In his view, the integration was less progressive than exploitative: the crowds, he believed, were drawn to the heightened risk and brutality, particularly when black prisoners were involved, as if to themselves witness hardened criminals “get their due”. The events pushed inmates into stunts that would never have been allowed in conventional rodeo settings, and Callies eventually stopped attending. What he saw, he said, was injury turned into entertainment and made more acceptable to spectators precisely because the men in danger were both criminals and/or black.

All of the “convict cowboys” as they were called then (though they themselves disliked the moniker), even those serving shorter sentences, found that their rodeo careers effectively ended at the prison gate. Competing on the outside required approval from the Rodeo Cowboys Association (RCA), which rejected riders with criminal records, leaving most former inmates with no path back into professional competition after their release. Many would nevertheless put their skills to use on the outside, such as two-time Top Hand winner Rusty Huff, who said he would go back to cutting horses as soon as he was released, dying in 2014 and having been a “lifelong cowboy” according to his obituary.

Yet despite the decades of success, cracks, literal and metaphorical, began forming in the 80s. Tastes changed. Attendance declined. Maintenance was deferred. None of the profits were set aside for repairs. By 1986, structural problems forced the closure of the arena. The state, flush with new federal funding for inmate education and recreation, no longer needed rodeo revenue, and the Legislature refused to spend $500,000 to fix the bleachers.

Additionally, the prison administration was concerned that the mounting costs of liability insurance for the rodeo’s performers and spectators, now necessary, could not be covered. The final rodeo was held in 1986. In 2012, the arena itself was demolished following concerns the structure would collapse onto the nearby road.

Attempts to resurrect the rodeo surfaced throughout the 1990s and again in 2019, when State Rep. Ernest Bailes filed a revival bill that went nowhere. While Oklahoma has considered starting a successor event, the Angola Prison Rodeo in Louisiana, launched in 1965, remains the only public prison rodeo still operating.

“This wasn’t a professional rodeo,” photographer Bill Kennedy, who documented the event from 1977 to 1980 as a University of Texas graduate student, later said. “It was a show.” He recalled that his first visit to the rodeo felt unreal, almost disorienting. With each return, he built trust with a core group of regular competitors, gaining access that went beyond the spectacle. The photographs are drawn from an extensive project produced with fellow student Michael Murphy, capturing one of the clearest pictures of the event in its later years.

Though the rodeo itself is long gone, it endures in university and museum archives across Texas and in other collections beyond. Kennedy, now Professor Emeritus of Photography and Media Arts at St. Edward’s University in Austin, continues to sell prints from the series through his official website. The Texas Prison Rodeo also survives in memory, still discussed, debated, and revisited, an enduring reminder of a time when two unlikely worlds briefly, and uneasily, collided.

The legacy of the Texas Prison Rodeo remains unsettled. Critics question whether it was rehabilitation or exploitation, opportunity or spectacle. What is clear is that for more than fifty years, every Sunday in October, thousands of Texans paid to watch men with nothing to lose take on extreme danger in front of a cheering crowd. For the many inmates who volunteered, those quick few seconds on a bull were less about performance than the change of pace: a brief break from routine, confinement, and the rigid limits of prison life, perhaps offering a kind of freedom they would otherwise never experience again.