Forget Japan—This small Baltic country is possibly the true master of surreal and weird animation, here are the films that deserve a spot on your watchlist.

Animation is a glorious beast of a medium, but like an eccentric relative at a family gathering, it’s often politely ignored unless it’s from the US or Japan. The art form is usually reserved for the world’s two biggest animation factories, leaving the rest of the globe’s animated contributions to languish in obscurity. Thankfully, Soviet and Eastern European animation has finally started to get some overdue attention in recent years, and a lot of that stuff is the visual equivalent of a fever dream. But if we’re really talking about weird, Estonian animation is in a league of its own, giving even the Japanese masters of the bizarre a run for their money.

My own journey into the world of Estonian animation began when I was exposed to the works of Priit Pärn. It was like finding out Salvador Dalí found a moment to collab with George Orwell. Pärn’s creations are nothing short of a delightful assault on the senses—his animations look like what would happen if your darkest fears and most absurd thoughts were given life and set loose in a playground of chaos. This guy didn’t just draw; he spawned a whole generation of animators who specialize in a brand of surrealism that’s equal parts disturbing, hilarious, and utterly addictive. Imagine a magnifying glass zoomed in on the paranoia, horror, whimsical stupidity, and irrational banality of daily life. That’s Estonian animation for you.

The real tragedy here? Estonian animation is practically a ghost outside of its homeland, only haunting the occasional animation festival, where even then, the old classics are often kept locked away like some kind of forbidden treasure. In fact, Estonia as a country is pretty obscure already, and unfortunately, I don’t think most people can even point to it on the map. So this is double obscurity we’re dealing with here. But fear not, intrepid explorer of the strange and beautiful—we have the internet to solve that problem for us, and we can become wise to this world without having to book a flight to Tallinn.

In a quest to unearth this obscure goldmine, I sacrificed hours of my life—meaning I binge-watched around 50 of these animations from the comfort of my bed over a few days. Here are the absolute best slices of the Estonian mind that I discovered in the process.

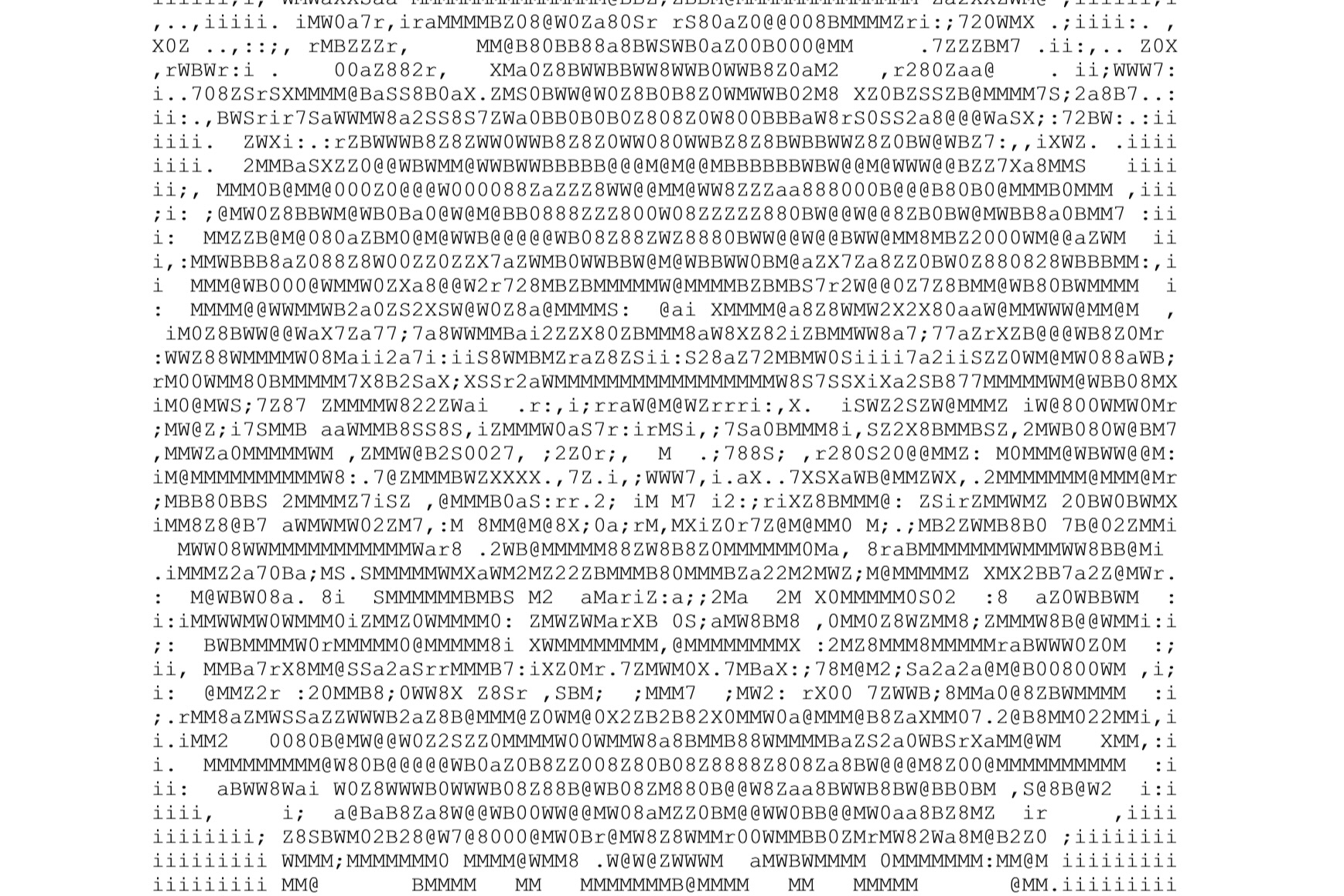

Värvilind (1974)

Estonian animation got its big break in 1971 when Rein Raamat decided to forego the Disneyesque conventionality of the Soviet animation establishment and set up Joonisfilm, a rebel subdivision of his old home at Tallinnfilm studio. That’s when things got interesting. Raamat started cranking out films that took experimentation to new heights. Case in point: “Värvilind” (Colorbird). It’s a trippy mash-up of psychedelia, sci-fi, and Soviet family values, set in a monochromatic future city that suddenly explodes with color. Picture kids playing amidst vibrant hues and birds flitting about (and a malicious giant cat)—a heady mix of joy, discovery, hesitation, unease, and optimism.

“Värvilind” is also a prime example of how Western media snuck past the Iron Curtain. The visuals scream influences from Peter Max, the artist behind the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine,” Piet Mondrian’s angular paintings, and Hariton Pushwagner’s sprawling cityscapes. It’s like these animators had a clandestine love affair with Western pop culture. This one’s a visual feast, so maybe queue it up the next time you’re feeling adventurous—perhaps with a tab of acid for good measure. And if you still haven’t had your Soviet psychedelia, then watch Raamat’s Lend (Taking Off) from three years later, it’s the first animation that put Joonisfilm on the map internationally.

Ja Teeb Trikke (1978)

While Raamat’s work had some semblance of a message buried under its chaos, Priit Pärn’s animations are almost pure, unadulterated absurdism. Pärn, who started off as a plant ecologist, then dabbled in caricature, and finally found his calling as an animator at 30, developed a style that is both cynical and crude. His wobbly outlines and fluid, biting satire on the human form bring to mind Mike Judge’s work—except Pärn was doing it 20 years earlier and on the Soviet dime.

Take “Ja Teeb Trikke” (And He Plays Tricks), for example. This one features a green trickster bear who can warp time and space to his will, much to the annoyance and entertainment of the other woodland creatures. It’s like someone took shrooms and decided to remake Winnie the Pooh. And believe it or not, this is one of Pärn’s tamer pieces. You can almost imagine it being shown to kids, back in the day.

Not surreal enough for you? Then “Aeg Maha” (Time Out), made six years later, is your ticket to the bizarre. The plot? A raccoon gets woken up by an alarm clock. That’s about as much sense as I could make of it before I stopped thinking and just kept watching. Honestly, just see it and let the absurdity wash over you.

Suur Tõll (1980)

“Suur Tõll,” (Tyll the Giant) is a film that supposedly had Estonian kids hiding under their blankets after it aired on state TV. This one ditches the future psychedelia vibes for a deep dive into the past, adapting the local legend of Toell the Great. Toell, a giant god, is said to have lived on the Baltic island of Saaremaa, defending it from an invading army. And defend he does, with the kind of brutal, bloody battles that would make slasher film directors take frantic notes—think heads flying and spears impaling left and right. It’s a raw, unfiltered look at the horrors of war and the hefty price of peace, showing that even gods aren’t immune to suffering. No wonder some kids were left traumatized.

If you’re curious about Estonian folklore or just have a passing interest in anything macabre, “Suur Tõll” is worth your time. But for something a bit lighter, Raamat also gave us “Kilplased.” This cartoon is based on a 19th-century account of a village of bumbling highlanders in Germany and their endless, hilarious struggles with nature and farming. Written by one of Estonia’s classic folk authors, this story was so impactful that the name of the village, the cartoon’s namesake, became shorthand for “idiot.” Talk about a legacy.

Harjutusi Iseseisvaks Eluks (1980)

“Harjutusi Iseseisvaks Eluks” (Exercises for an Independent Life) is the first of Pärn’s animations to tackle the mundane horrors of everyday life head-on. There’s a recurring theme in Estonian animation about the interaction of conformity with absurdity, where doing everyday things begins to feel uncomfortable and alienating—like one day you look down, and your suit is suddenly three sizes too big and the telephone you’ve used for ten years got moved slightly to left but your muscle memory is still reaching for it in the old place every time. This 1980 gem feels like two cartoons accidentally got scheduled at the same time, stumbled into each other, and merged on your TV screen.

It kicks off with a whimsical boy frolicking in the woods, befriending animals, and having a grand old time. Then, without warning, it shifts to the soul-crushing routine of a man in a suit—filing papers, answering phones, watching TV, reading the newspaper. This mundane cycle loops until the two worlds collide in a gloriously chaotic breakdown. The boy and the man swap lives, each trying to navigate the other’s reality, highlighting the stark contrast between the carefree whimsy of childhood and the drudgery of adult professional life.

In the end, the meeting of these two worlds is a solid reminder of the clash between adolescent dreams and adult responsibilities, leaving you to wonder just how much of your “independent life” is truly your own.

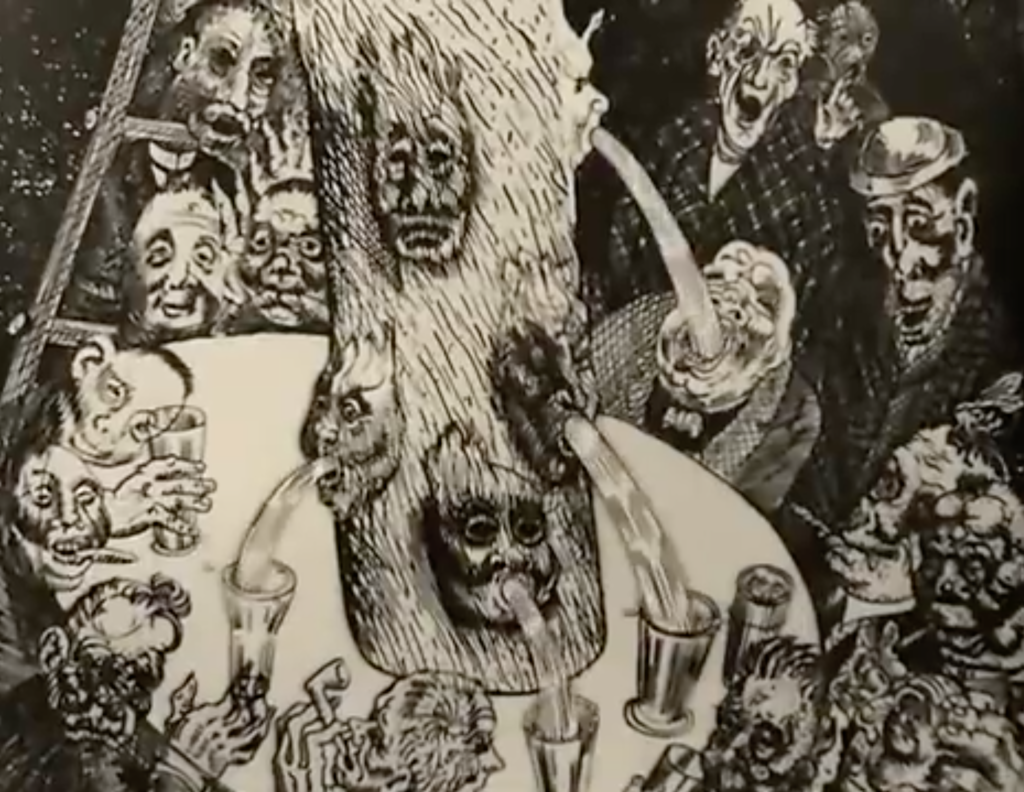

Kolmnurk (1982)

“Kolmnurk” (Triangle), another gem from Pärn’s oeuvre, takes a sharp look at the monotony of daily life and the strain it places on relationships. This 1982 animation is an allegory for marital infidelity, evidently a frequent theme in Estonian animation. The story follows a disinterested husband and his wife, who is obsessively trying to cook him dinner. Enter a strange, tiny man from a door below the counter, who tempts the wife into letting him eat all the food, eventually causing the husband to leave. Neither man shows any real interest in the wife, who remains wholly engrossed in her culinary duties as if that’s her sole purpose in life. The couple eventually reconciles, and the tiny man returns to his tiny apartment, where he has a tiny wife of his own. The cartoon wraps up with a sobering statistic: “According to the Department of Statistics of the USSR, in 1980, for every 1000 marriages, there were 473 divorces. It makes you think, doesn’t it?”

While most of Pärn’s work slid past the Soviet censors, this one ruffled some serious feathers. The censors labeled it “insulting to Soviet women.” But Pärn, ever the smooth talker, managed to haggle them down from cutting a whopping 8 minutes to a mere 1.5 seconds. The compromise? Only 20 prints of the film were made instead of the 400 originally planned. And instead of sending it off to obscure film festivals, as was intended, it got local play only–prime-time exposure on Soviet television, beaming into the homes of about 100 million viewers. A triumph for artistic integrity and a colossal facepalm for Soviet logic.

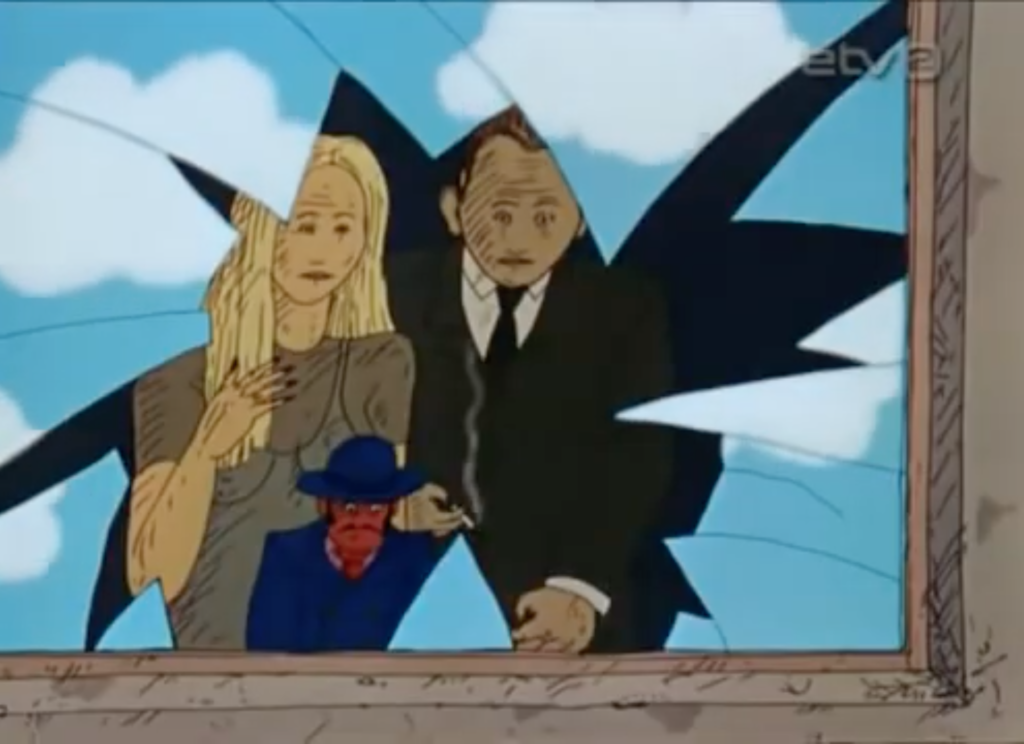

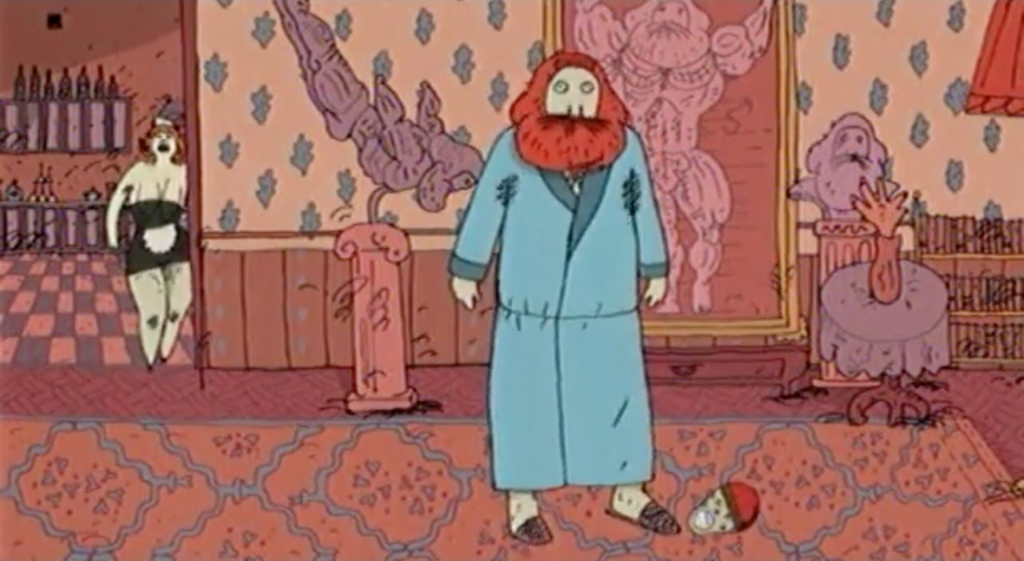

Põrgu (1983)

Raamat’s magnum opus, “Põrgu” (Hell), is a grotesque parade of humanity’s worst vices. Picture a freak show where the main attractions are drunkenness, eroticism, obesity, and all those other charming qualities. This film rips its imagery straight from the drawings of Eduard Wiiralt, a fellow Estonian who, in the 1930s, had a knack for disfigured subjects and unseemly themes. Raamat faithfully adapts Wiiralt’s twisted visions, flinging them at the viewer in a way that’s as unsettling as watching the Hindenburg disaster in slow motion. It’s arguably Raamat’s most socially insightful work, laying bare the dark corners of human nature.

A few years later, Raamat took on another adaptation, this time from the Belgian artist Frans Masereel, inventor of the “wordless novel” and unintentional forefather of the graphic novel. In 1988’s “Linn” (The City), he turned Masereel’s woodcuts into an animated depiction of a city overrun by a massive invasion of black squares—a not-so-subtle metaphor for industrialization under capitalism. If “Põrgu” showed the personal sins of mankind, this one was a damning display of how modern society crushes the human spirit.

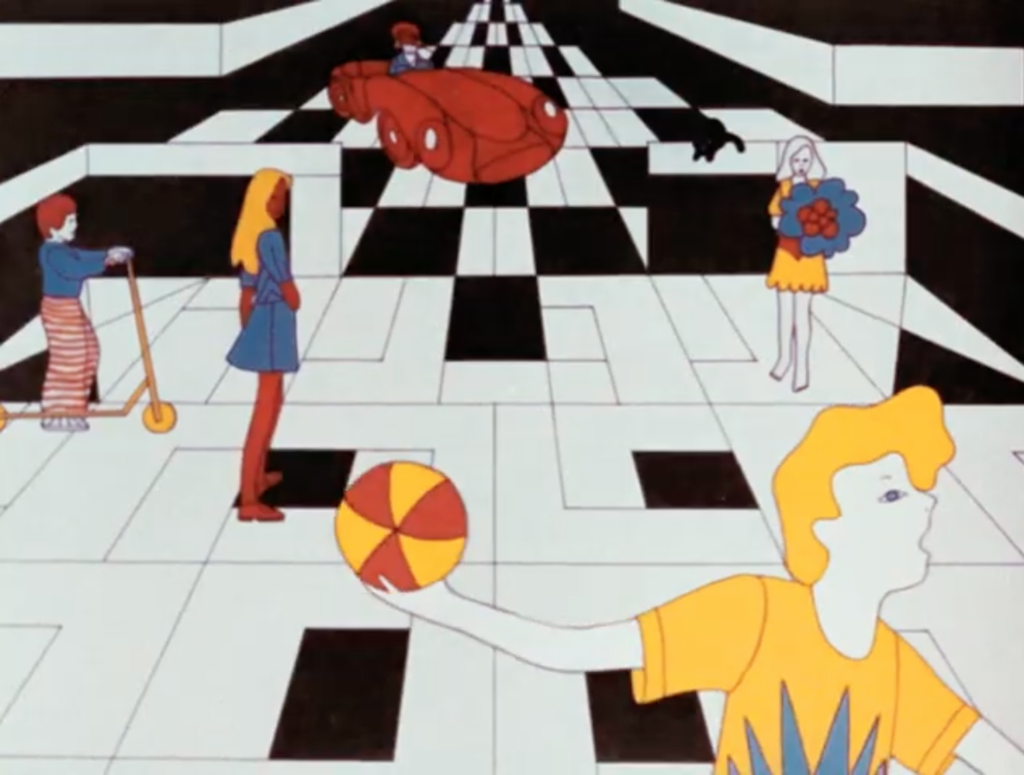

Eine Murul (1987)

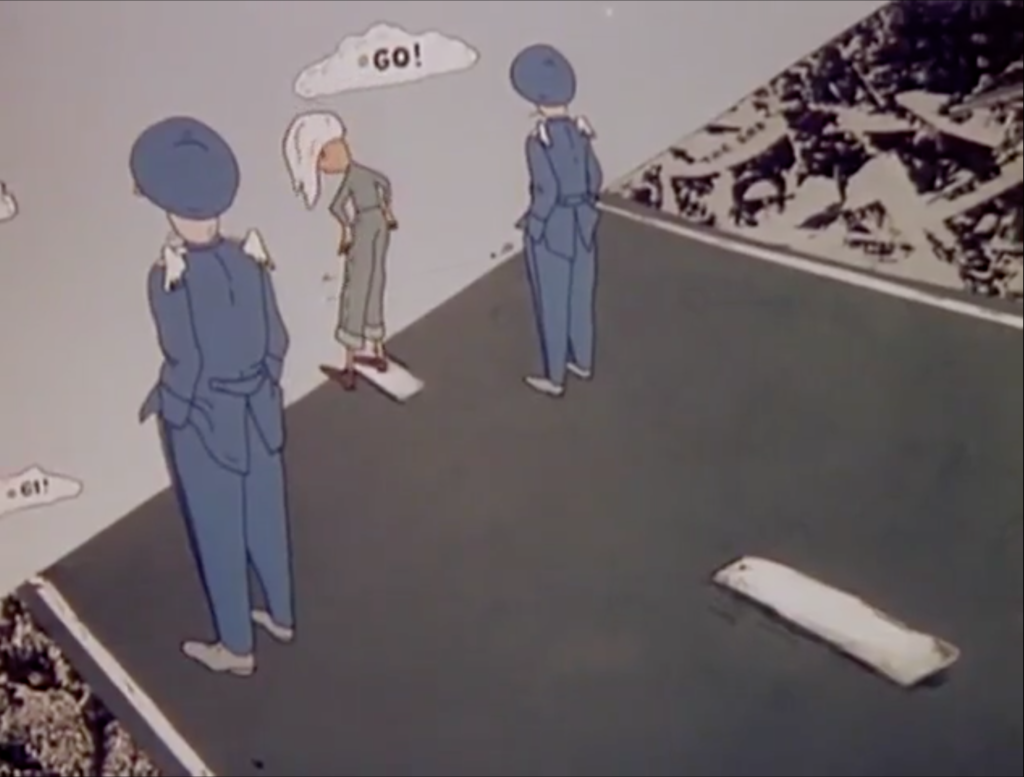

This is the first animation that led me to discover Estonian animation in the first place, and it remains my favorite. Pärn’s pièce de résistance, Eine Murul (Breakfast on the Grass), dives headfirst into the drudgery of four poor souls caught in the not-so-subtle grip of a baltic soviet nightmare. Think bread lines, command economies, bureaucracy—basically, a love letter to life under communism, but with more dark humor than you’d hear from a mortician.

Each character’s struggle is laid bare in their own little vignette, each time wrestling with the horrors of conformity, the cruel march of age, or the arbitrary whims of the state. In one scene, the bust of a leader on top of a plinth slowly melts and drips off its place, to be replaced with a new bust, ostensibly the new boss. One of the characters makes a sheepish gesture of approval in the presence of two figures in trench coats, most likely the KGB, keeping them at bay. In another scene, a character navigates a series of bread lines with the hope of acquiring increasingly ordinary items to barter with in order to get a new suit made, as nobody sees any value in state-issued paper money.

The heroes of the story eventually end up picnicking in a park together, taking their places to channel that famous Manet painting the animation is named after, itself a piece of art in which the subjects are aware of the viewer, which is just a cheeky way to remind us they’re all unwitting, but aware, subjects in the surreal art piece that is life under totalitarianism.

Made when the Soviet Union was on its last legs, this animated gem offers a scathing critique of the very system that birthed it. It’s like Pärn had a front-row seat to the circus and decided to throw popcorn at the clowns. Sure, it’s bleak, and the humor’s darker than a solar eclipse on a Finnish winter, but every frame screams with life experiences that beckon you to take heed.

The film kicks off with a cheeky dedication to “artists who went as far as they were allowed”—as if to say, “Cheers to the brave souls who dared to create and got imprisoned for it!” Yet, it wraps up on a surprisingly uplifting note: even in the middle of chaos, a handful of friends can still gather to create a memory worth remembering.

Pilares (1989)

Here’s another view of Soviet-era Estonia. Pilares (The Pillar), courtesy of Heiki Ernits, delivers a surreal and bleak world on par with Pärn’s greatest hits. The first half is a grim commentary on Soviet healthcare, following a poor sap who’s “treated” by a gaggle of sadistic doctors, seemingly cured and released, only to immediately relapse into illness amidst the chaotic grind and dog-eat-dog desperation of city life.

In the second half, we switch gears to a massive communist Tower of Babel project. Every scrap of human potential is exploited and sacrificed under the ambivalent, even carefree, gaze of bureaucrats, who are too busy rolling people over with their desks and giving each other medals to care. Just when the colossal structure seems finished, chaos erupts. The same workers swarm the tower, greedily trying to pilfer a piece for themselves, only to find out the bricks they are yanking are the very foundation holding up the sky. Naturally, the whole thing is poised to come crashing down. And in real life, I guess it did.

Much like Pärn’s “Eine Murul,” this piece paints the mob as just as much a threat to your soul as the government, everyone locked in a vicious cycle of mutual destruction. Whether Pärn directly inspired a generation of animators or they all just suffered through the same grim reality is unclear, but the similarities in style and tone are unmistakable.

His Wife Is A Hen (1990)

Alright, so this one isn’t technically Estonian but it gets an honorable mention. It comes from Russian animator Igor Kovalyov, a guy who heavily channeled Priit Pärn’s surreal vibes. Kovalyov would, soon after the making of this film, pack his bags for the USA and work on shows for Nickelodeon, namely Rugrats. But trust me, you wouldn’t guess it’s the same guy.

“His Wife Is a Hen” needs just the right amount of explanation: it’s about a blue dude and his wife, who—shockingly—is a hen. They also have a pet that’s a caterpillar with a human head. Classic. In Russia, “hen” is slang for a housewife who’s glued to home duties with no interest in her own life. Things are going as smoothly as they can in their bizarre household until a mysterious, suited man strolls in and drops the bombshell that the wife is, indeed, a literal hen. The husband is gobsmacked. True to its Estonian influences, their marriage hits the skids, and the chaos that ensues is anyone’s guess. I should take this moment to mention that besides making Rugrats, Kovalyov was a co-creator of Aaahh!!! Real Monsters, if that helps things make any more sense.

Kovalyov’s other works are also worth a peek. His 1992 film Andrei Svislotskiy is based on a story witnessed by his eponymous fellow Russian animator during his childhood in the village of Bucha, Ukraine. It’s about a villager and his two servants who spy on him, witnessing his mental breakdown and the consequent collapse of his home. Think arthouse pacing with a bleak, enticing narrative.

During his stint in America with animation powerhouse Klasky Csupo, Kovalyov churned out three animations of his own. First up was 1996’s Bird in the Window, which, surprise surprise, revolves around a crumbling marriage. It might not be as surreal as his other works, but it’s dripping with symbolism. Two Chinese guys playing checkers in the house—what’s that about? I might need a rewatch or two to crack Kovalyov’s code on that one.

Ärasõit (1991)

One more gem from Ernits, and it’s easily in my top three: “Ärasõit” (Departure). This one’s set on a moving train, where a man leaves his wife’s carriage to embark on a quest through every train car in search of hot tea to refill his cup. What he finds instead is a circus of drunkards, revolutionaries, shady schemers plotting world domination, and all sorts of colorful characters. At some point he almost gets his hot tea, at the cost of his soul, in another scene, some communists confiscate his nice glass cup and replace it with a substandard mug. That’s the way life is sometimes.

As he navigates the train, it feels like he’s traveling backward through different eras of Estonian and world history. In one car, we’ve got President Bush and Gorbachev casually redrawing Europe’s borders. Two dudes in German flag shirts meet, one scrubs off an East German-sized stain from the other’s flag, and they shake hands like it’s all in a day’s work. A few train cars down there’s a brief, ominous encounter alone with the Russian royal family, followed by a room full of ragged revolutionaries smashing samovars and polishing their boots with a dress snatched off the body of a statue.

This film is a rapid-fire tour through the Estonian historical psyche, packed with details that make it worth a second or even third viewing. It’s a brilliant, surrealist ride that captures the essence of history and absurdity all in one go.

By the way, if you were a fan of Raamat’s nostalgic trips through old Estonian folklore, you’ll want to check out Ernits’ 1994 animation, “Jaagup ja Surm” (Jaagup and Death). In this tale, a humble village farmer encounters Death, who’s come to collect his soul. But in a twist, Jaagup persuades Death to let him live indefinitely, dooming him to witness centuries of Estonian history unfold before his eyes. It’s a classic “be careful what you wish for” tale, deftly packed into a short but compelling watch.

Hotel E (1992)

Hotel E is another piece by Pärn, cranking out his first piece since Estonia woke up and smelled the democracy coffee. He’s still got that acerbic tongue and savage critique of the socialist dystopia they all love to hate. Like a callback to “Exercises for an Independent Life,” an examination of what happens when two worlds collide, this time the vividly colored, supercilious West, and the dingy, soul-sucking East.

Westerners are rendered with the precision of a Peter Max fever dream—yes, like Raamat’s “Colorbird” from earlier. Meanwhile, Easterners are trapped in Pärn’s trademark twisted version of reality, looking like something a paranoid schizophrenic might doodle on a bad day—bloated figures sitting in a poorly lit purgatory.

In this delightful hellscape, our Eastern neighbors are held hostage by a malevolent cloud of politburo flies, condemned to an eternal game of teacup chicken, desperately trying to avoid getting their cups smashed by a swinging clock hand, the penalty for failure or escape being swarmed and chomped by the buzzing state security apparatus mob. Meanwhile, just beyond the door, their Western counterparts are living in a permanent sitcom rerun—sports, TV, and material abundance, represented by one guy’s endlessly looping routine of smashing the same vase. Real high stakes there.

One poor soul keeps trying to bolt for the exit, determined to bask in the technicolor sunshine. Every attempt reeks of desperation to ditch the fly-infested nightmare. The symbolism here is thicker than a Cold War bunker wall and about as subtle as a brick through a window.

Sünnipäev (1994)

From the twisted genius of Estonian animator Janno Põldma comes “Sünnipäev” (Birthday), which isn’t so much devised and animated by Põldma as much as it is by his team, which in this case happens to be an entire class of little schoolchildren. This animation is hands down one of the most bizarre and jarring pieces on this list, leaving you to wonder what kind of lives these children were living that led them to produce this piece of animation.

There’s no coherent dialogue—mercifully chosen, I should say because it wouldn’t help anyway. Picture a bunch of crudely drawn animals in a city, with equal parts silly nonsense and random violence. There’s a birthday party, a green goblin with a knife, mischievous pointy-hat elf dudes causing chaos, and sporadic gunfire. Halfway through, the green goblin throws a mask on, ready to go on a knife-wielding rampage against the pointy hats. A pig tries to show him that love can conquer all, but the goblin quickly decides that love is not enough and sticks to violence.

It’s like your childhood fridge drawings came to life and embarked on a chaotic crime spree. Remember, kids came up with this—and even they don’t look happy about it by the end. If you’re wondering how this ever got the green light for children, well, it’s because the kids themselves were the masterminds. Can’t expose them to violence if they’re creating the violence in the first place. Children are wild, man.

Gravitatsioon (1996)

Another relatively recent addition to the animation scene, Priit Tender, kicked off his career in the late 90s with “Gravitatsioon” (Gravitation). The story centers around a young boy who dreams of flying by any means, no matter what the laws of physics say. To achieve this, he sets off to find the edge of the world, hitchhiking with random passersby and navigating all the quirks of being in the car with them.

When he finally reaches the edge, he attempts to figure out how to fly. The film closes with a thought-provoking quote: “But is free fall really freedom? And what kind of freedom? Heavenly or earthly? Is love a physical phenomenon? Can a lover fly to heaven? Can falling be flight? What prevents us from flying? Earth? Can air resistance stop falling? Can resistance be free?” I couldn’t find a version of this animation on the internet with English subtitles, but you can still enjoy the journey without them.

Porganite öö (1998)

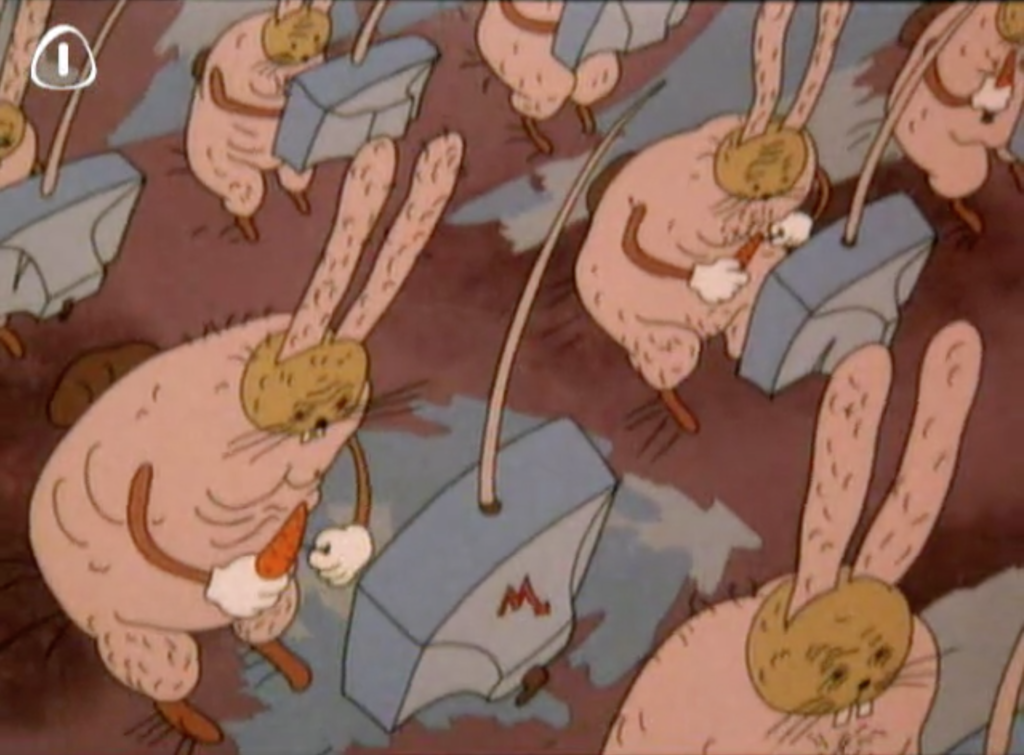

Continuing with the whole hotel motif, Pärn’s other 90s gem, Porganite öö (Night of the Carrot) seemingly eschews politics and dives headfirst into pure, uncut surrealism. And bad news for the linguistically challenged: there’s no English-subbed version floating around the internet. So unless you can banter in Estonian, prepare for a double masterclass in bewilderment.

From what I could piece together, a humble bicyclist named Diego is trying to snag a room in a hotel jam-packed with oddballs. One room houses a skeletal painter obsessed with curvy women—Freud would have a field day. Down the hall, there’s a cellist who’s evidently not a cellist but actually a colossal gelatinous blob filling the entire room. And just when you think you’ve hit peak weirdness, you learn about a secret cabal of anthropomorphic rabbits living on the top floor. These bunnies aren’t just chilling; they’re running the world, of course, keeping planes aloft and plotting to relocate underwater to produce their own ketchup—because, obviously, ketchup is 80% water. Makes perfect sense, right?

The humor here is top-notch (if you could understand it). There’s a scene where the hotel concierge inspects Diego’s passport, squashes a cockroach with it, and then nonchalantly apologizes: “Sorry, I don’t have my own passport, I’m an illegal immigrant.” It’s the kind of bizarre, deadpan line that feels ripped straight from a Daniil Kharms poem. Also, the love interest of the story is a hard-boiled egg that speaks German.

Mont Blanc (2001)

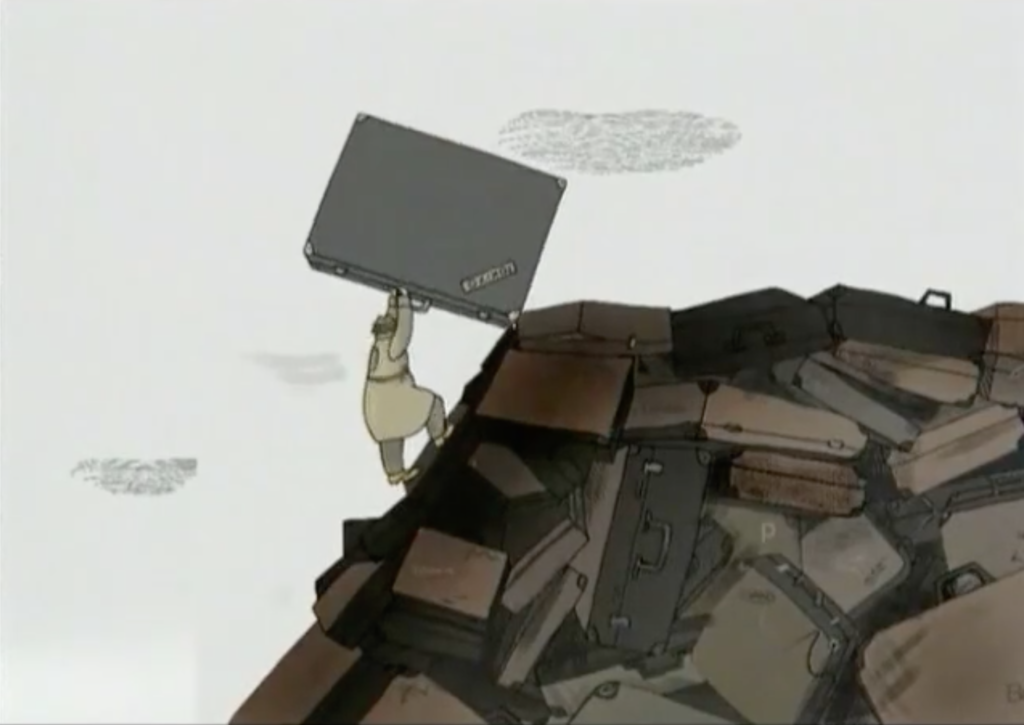

In Mont Blanc, yet another cinematically loaded film from Tender, we delve into the saga of a Japanese salaryman who, tossing home and hearth to the wind, packs up his suitcase and embarks on a quixotic quest to conquer Mt. Fujiyama, only to find himself shedding bits of body and spirit along the way. Amidst the rugged slopes, he stumbles upon a surreal sight: a trail of other besuited businessmen, each hauling their own suitcase up a mountain made entirely of discarded suitcases from previous attempts. It’s a poignant allegory of the perils of forsaking the familiar for lofty ambitions, where every step upwards seems to mirror a descent into personal and professional catastrophe.

Karl Ja Marilyn (2003)

Karl & Marilyn is another wild ride from Pärn, and while it’s easier to follow, it’s still as bizarre as ever. A ridiculously buff Karl Marx, idolized for his Herculean physique, is tired of it all and decides he’s done with fame. So, what does he do? Shaves off his iconic beard and hair to start fresh, naturally. But he can’t leave loose ends, so he offs the barber. The twist? He gets photobombed in the background by some guy trying to impress his ex with fish pics, which tips off a detective.

Meanwhile, Marilyn Monroe is being held captive by an old hag demanding her every whim be catered to with haste. Marilyn, ever resourceful, saws off the legs of the old lady’s chair, sending her tumbling to her death. Free at last, Marilyn struts the streets, dazzling anyone lucky enough to catch a glimpse. Of course, in true Pärn fashion, their paths inevitably cross.

Still craving more Pärn? Dive into “1895”, his fantastical take on the lives of cinema pioneers Auguste and Louis Lumiere, packed with film and historical references for the film buffs out there, created exactly a century to the official year that cinema began, hence the name. Or check out “Tuukrid Vihmas” (Divers In The Rain), one of his collaborations with his wife. This one’s a bit more serious—following the strained marriage of a day-shift rescue diver and a night-shift dentist who are never home at the same time. It only snagged 18 awards and became Estonia’s most celebrated animation ever, no biggie.

Ahviaasta (2003)

Ahviaasta (The Year of the Monkey) is another top favorite of mine comes from the relatively contemporary animator Ülo Pikkov. This one’s a wild ride: a chimp switches places with a drunken man dressed as Santa who stumbles into the zoo at night. The authorities, none the wiser, pick up the chimp-Santa, shave him, treat his supposed alcoholism with shock therapy, and then release him into the human world.

Our freshly shaved chimp’s first instinct? Grab a couple of fence boards and become a champion Olympic skier. Naturally, he falls in love with a woman who looks like the Statue of Liberty while receiving his award. Determined to see her again, he accidentally wins the lottery and keeps his streak going by becoming a celebrity actor, a renowned rockstar, and more, all in the hopes of reuniting with his Liberty lookalike.

It’s already a hilarious watch, but I couldn’t stop cracking up throughout, imagining Karl Pilkington narrating the whole thing like one of his Monkey News segments. “Turns out.. the skier who took first place? Little chimp fella..”

If you want to see more Pikkov, his student project from the Turku School of Art and Communication, “Cappuccino,” is a must-watch. It’s a quirky little piece about Paul, who’s wallowing in post-breakup misery over his ex, Laura, only to be interrupted by a mosquito, which he spares no moment in squashing. Turns out that mosquito had a husband, who tries to escape the grief by drowning himself in Paul’s coffee, which inspires Paul to take a similar course of action, with a surprising twist at the end. We’ve all been there—sometimes you’re Paul, and other days you’re Georg.

Krokodill (2009)

As promised, let’s dive into Kaspar Jancis, a fresh face on the Estonian animation scene. His film Krokodill (Crocodile) is a wild ride through the life of a down-and-out opera singer who loses his job when he loses his voice. Reduced to wearing a crocodile costume as a punching bag mascot at a shopping center patronized exclusively by bratty, unsupervised kids, his only friends to keep him company at home are a venus flytrap and a bottle of booze. Meanwhile, there’s a woman who makes daily trips to the meat market to feed a real crocodile she keeps in her bathtub. Naturally, their paths cross, and they fall for each other in a twisted take on domestic gloom and the pitfalls of romantic entanglements.

If you’re into this kind of offbeat storytelling, Jancis has got more gems for you, which he kindly uploaded onto the internet himself. He’s crafted tales about a woman too busy getting groped by a fly to notice her lover, an unlucky terrorist trying to blow up a statue during a marathon, a senile Soviet cosmonaut reliving his glory days, and a woman moving a piano who nearly gets framed for murder. With Jancis, boredom is not an option, I assure you.

Villa Antropoff (2012)

This gem by Jancis deserves its own spotlight because, let’s be honest, it’s his magnum opus. We’re talking about a tale of rich versus poor, fat versus skinny, young versus old, and all the delightful contrasts in between. Teaming up with Russian artist Vladimir Leschiov, Jancis spins the yarn of a destitute African standing at the ocean’s edge, where the detritus of the Western world occasionally washes ashore. Armed with nothing but a wooden crate as a raft and a used condom he found on the beach, he sets off on a quest for better shores.

Meanwhile, back in the land of cold winters and colder hearts, a coke-addicted Russian oligarch is getting hitched. The celebration? A descent into utter gluttony and excess with his fellow rich pals. Naturally, these two life paths worlds collide, but not quite how you’d expect.

Now, despite its relatively tame nature and the fact that the communist censorship board is just a ghost of Christmas past, this film still got the boot from YouTube for “nudity, pornography, or other sexually provocative content.” Seriously, a woman flashes her breasts for like five seconds. Big whoop. Luckily, it’s still up on Vimeo, where they apparently aren’t fazed by a bit of animated artistic nudity.

Koerkorter (2022)

Tender’s latest cinematic escapade, a bizarre blend of stop motion and 3D wizardry titled Koerkorter (The Dog Apartment), tackles life’s burning question: what happens when your apartment decides it’s also a dog? Picture this: a man wakes up to his flat trembling, growling, and demanding breakfast like a deranged bulldog. He appeases it with the last remnants of his sausage link stash before heading off to a job that involves performing ballet moves for cows in an effort to up their milk game. His wage? More sausages.

The film paints a bleak picture of desolation where the only landmarks in sight are the dog apartment, a forlorn dairy farm, and some uninspiring power lines. If you’ve got a soft spot for the gloomy charm of Eastern European decay, this flick’s your fix, complete with a hefty dose of despair, a broken-down lada, and the kind of vibe that makes you wonder if laughter is still a thing over there. Unfortunately, this one’s too new to be reliably available on the internet, and the link I had to it got taken down, so I guess you might have to fly to Tallinn for this one. Sorry.

Some years earlier, Tender teamed up with Kaspar Kancis, Ülo Pikkov, and the infamous Priit Pärn to cook up a feature-length film that clocks in just over an hour. An all-star lineup, what could go wrong? Let’s just say, Frank & Wendy is probably Estonia’s answer to Superjail before that even existed. Imagine Mulder and Scully from the X‑Files ditching aliens for a stint in Estonia. The result? More Baltic insanity, of course. In the first episode alone, they bust a clandestine sausage-making ring run by Nazi dwarves, complete with armbands and all, hell-bent on replacing the patties on burgers with bread and the bread with patties. Irreverent, nonsensical, and utterly insane.

I found a version online without subtitles and felt like I’d stumbled into a parallel universe trying to watch it. But if you’re up for the challenge, hunt down the full version on physical media that actually has English subtitles—I imagine it’s good viewing if you can understand it.

Conclusion

So, what pearls of wisdom have I gleaned from binging all these Estonian films? Well, it seems the Estonian flavor of surrealism is obsessed with a few very specific themes: the lurking dread of being investigated by mysterious men in trenchcoats, women accidentally losing their clothes, the misadventures of falling or climbing down manholes, floating away, everyday objects or the laws of physics going haywire, domestic life spiraling out of control, the sheer absurdity of authority figures, and, of course, marital woes. Seriously, Estonians really seem to have a thing about their marriages, don’t they?

Even though the specter of communism isn’t haunting Europe anymore, Estonian animation is still feeling the squeeze. As Pärn puts it, “During the USSR, restrictions were political. Now the limiting factor is money.” Animation is indeed a niche market, and it’ll probably stay under the radar for the foreseeable future, so don’t hold your breath for a Netflix-funded Estonian cartoon anytime soon.

Thankfully, the quirky charm of Estonian animation isn’t totally confined to one place, and sometimes it bleeds into everyday life. I stumbled across a whimsically animated 1996 commercial touting the virtues of using condoms. And our beloved Priit Pärn directed a PSA against wasting electricity, featuring a man leaving his wife and kids, only to return for a second to switch off the lights. The PSA ends with the message, “Before you leave, switch off the lights.” Brutal.