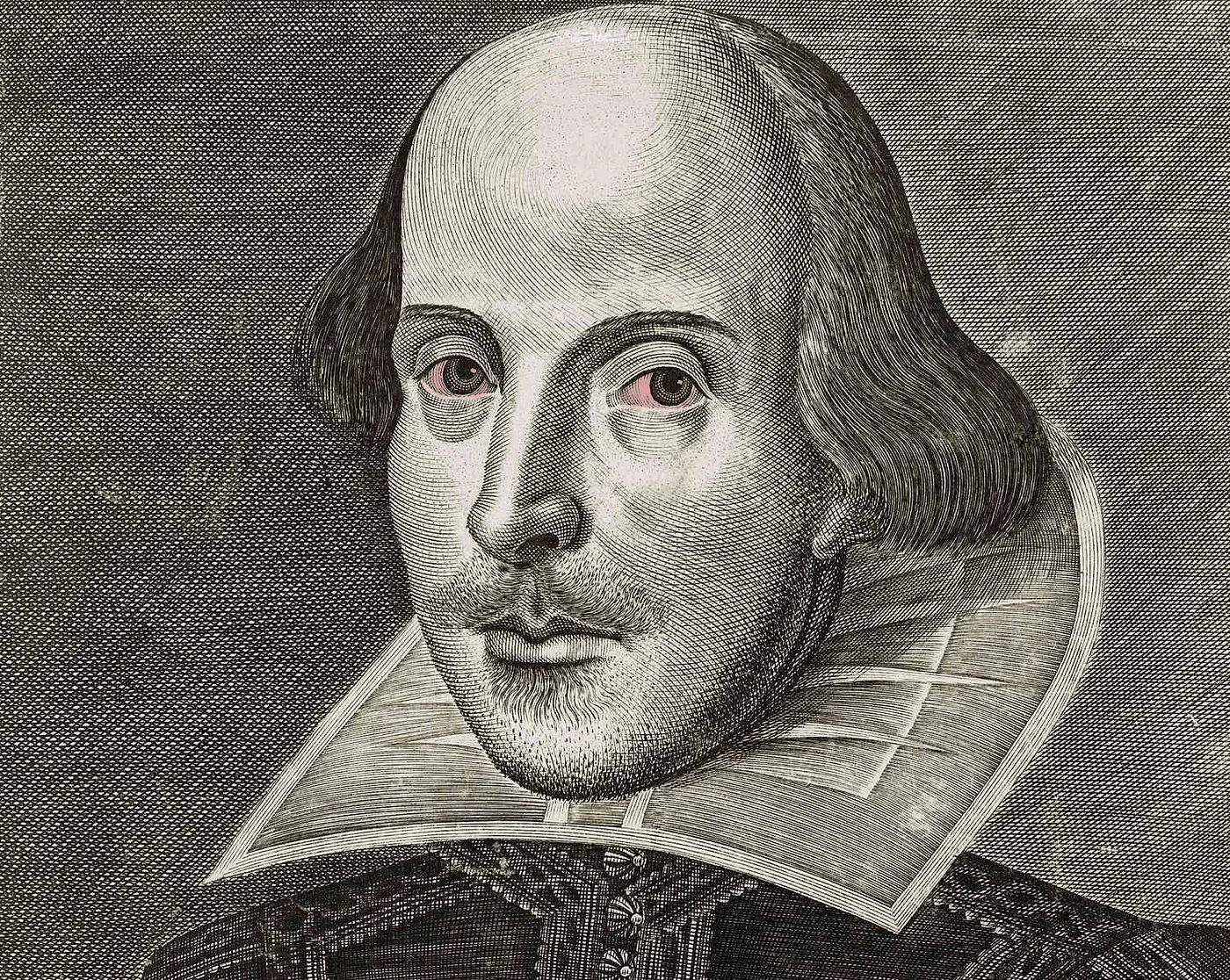

From clay pipe residues to cryptic sonnet lines, a long-running theory proposes that William Shakespeare experimented with mind-altering substances, raising questions about evidence, interpretation, and the enduring appetite for literary conspiracy. The evidence reveals as much about modern fascination as it does about the Bard himself.

Various substances from caffeine to LSD have been known to stimulate writers and artists across the centuries, but one historical conspiracy suggests that some of the greatest literary works of the Western world were not created with a sober mind. The speculation has continued for nearly two decades now, with tenuous studies being performed and radical, if ahistorical interpretations of Shakespeare’s work having fueled the debate. The theory is now almost three decades old, but does it amount to anything more than much ado about nothing?

The idea behind this burning issue was sparked sometime around January 1999 by Professor Francis Thackeray when he published a paper titled The Tenth Muse: Hemp as a Source of Inspiration for Shakespearean Literature? in an edition of the Occasional Papers and Reviews of the Shakespeare Society of Southern Africa. It was here that the seeds of a decade-long project were planted.

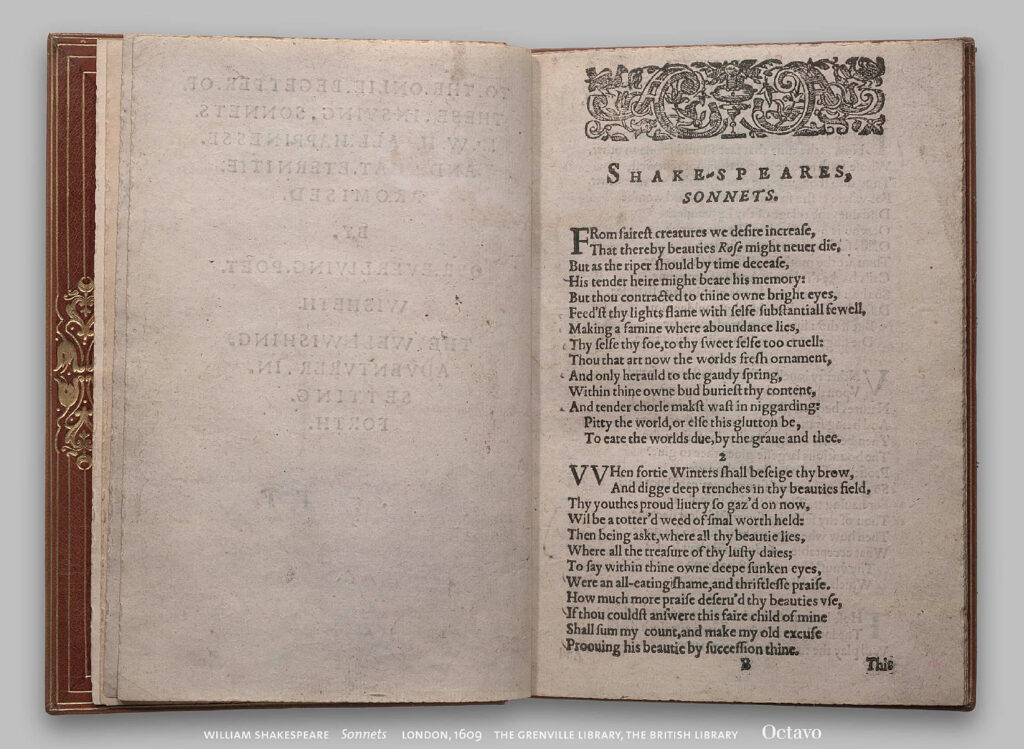

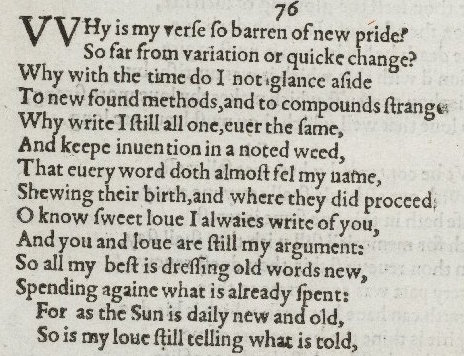

Thackery, a Yale-educated biological anthropologist and trained chemist who believes that the hard and soft sciences are not mutually exclusive, claims that his creative inspiration came from a reading of all of Shakespeare’s 154 known sonnets. One work in particular, known as Sonnet 76, refers to “new-found methods and compounds strange” and “invention in a noted weed” which Thackeray interpreted as a coded reference to the source of creativity (“invention”) resulting from the use of marijuana (“noted weed”). His critics beg to differ, but we’ll get to that.

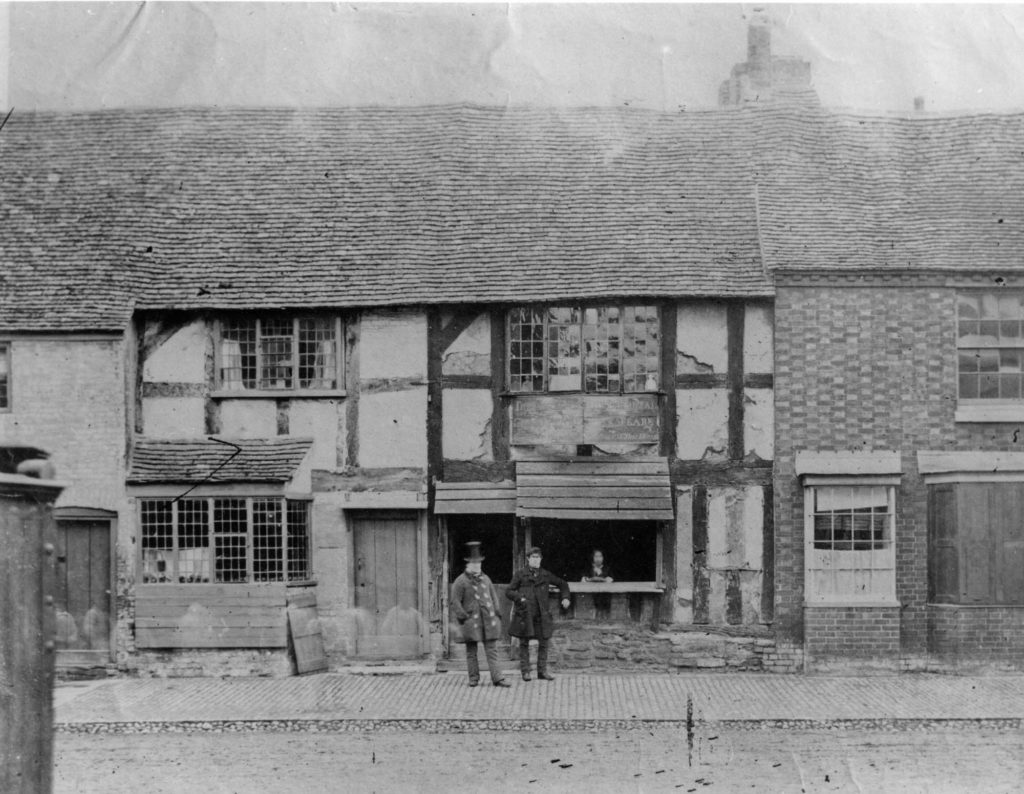

By this point, Thackery, then working at the Transvaal Museum in Pretoria and who usually specializes in prehistoric specimens, directed his methods to two dozen clay pipe fragments in the possession of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, dug up from the grounds of Shakespeare’s former homes of Straford-upon-Avon and New Place, the latter being where he spent his last days until his death in 1616.

The analysis of the pipes, through a process known as GCMS, or gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (most prominently used for explosive residue detection in transport hubs such as airports), was a joint effort carried out with the help of a colleague from his former alma mater of the University of Cape Town, Professor Nicholas van der Merwe as well as Inspector Tommy van der Merwe of the South African Police narcotics laboratory. Talk about being a narc, all of this effort, and getting the police involved essentially just to pin some drug charges on a guy who’s been dead for over 4 centuries.

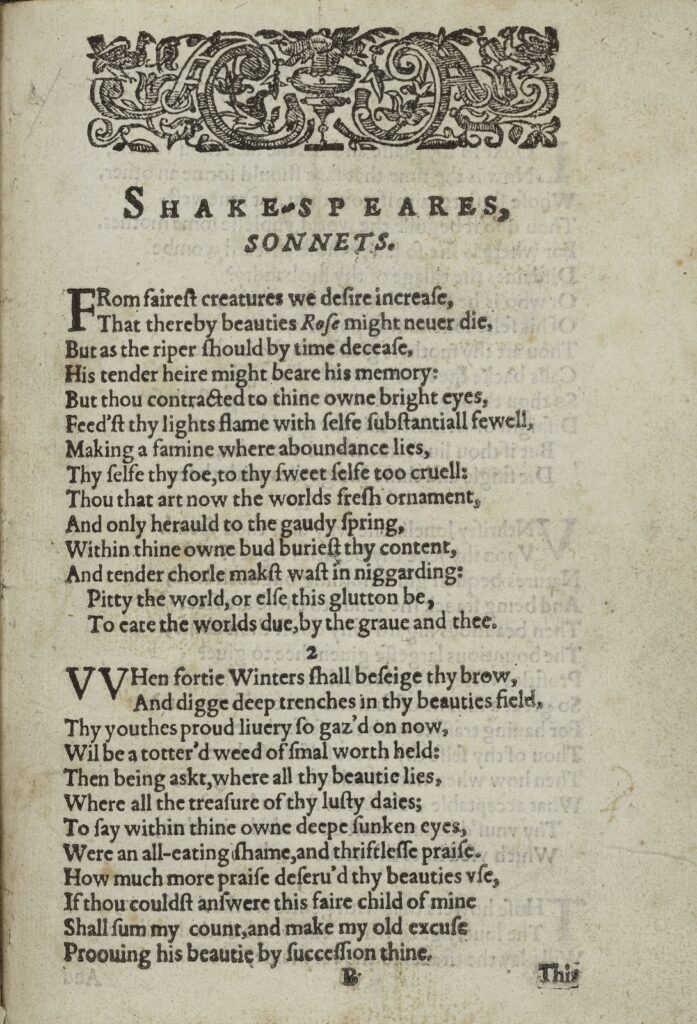

The technique is, of course, very sensitive and can pick up very slight residues, even ones that have been combusted and are liable to break down after only a few years of being in the ground, as is the case with cannabis resin. In an unrelated study, Professor van der Merwe produced similar results in his tests of Ethiopian pipes from the 15th century. An in-depth article describes the process thus: “Residues and sediments from the interior of bowls and bores of pipe stems were treated in 5‑mL chloroform to extract organic compounds. The organics were then concentrated in 0.2‑mL solvent and analyzed by coupled GCMS using an HP 5890 gas chromatograph interfaced with a 5890 mass selective detector. Identifications were based on EI spectra expressed in terms of mass:charge ratios (m/z) and relative abundances of compounds in reference samples.”

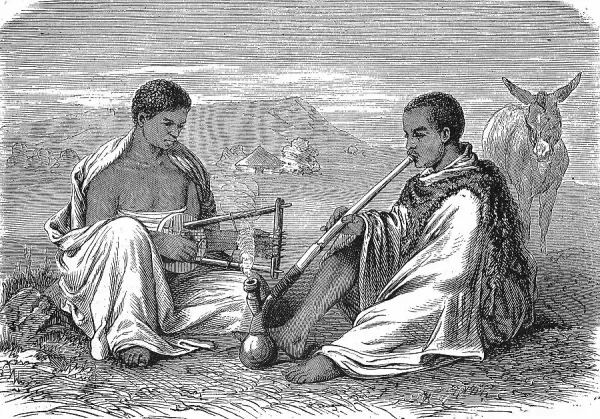

With expectations high, the tests were performed. Ultimately, the pipes were dated to sometime around the early 17th century, and despite being cleaned of most resin and dirt by restorers of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, eight of the samples showed signs of trace compounds associated with cannabis (namely cannabinol and cannabidiol) while two contained elements of Peruvian cocaine (erythroxylum) as well as the more conventional substance of nicotine (implying tobacco use), “more than we bargained for,” according to Thackeray. But that’s not all, the pipes were also found to have residue from camphor and myristic acid, the latter of which is primarily found in plants such as nutmeg, known for its hallucinogenic and dangerous effects, although these results were weeded out from the conclusions. A high point for the project indeed, and it was here where Thackeray found his opportunity to pipe up to the media to present his trailblazing results to the world.

But what does the world know now besides that whoever smoked these pipes was into some heavy shit? Regarding Shakespeare, nothing. But it does offer a window into the social history of England, as the earliest record of consumption of cocaine in Europe only dates back less than two centuries ago immediately following its successful extraction from coca leaves by German scientist Friedrich Gaedcke in 1855. So at the very least, it rewrites the complete history of drug use in England, a story for which no written records seem to exist.

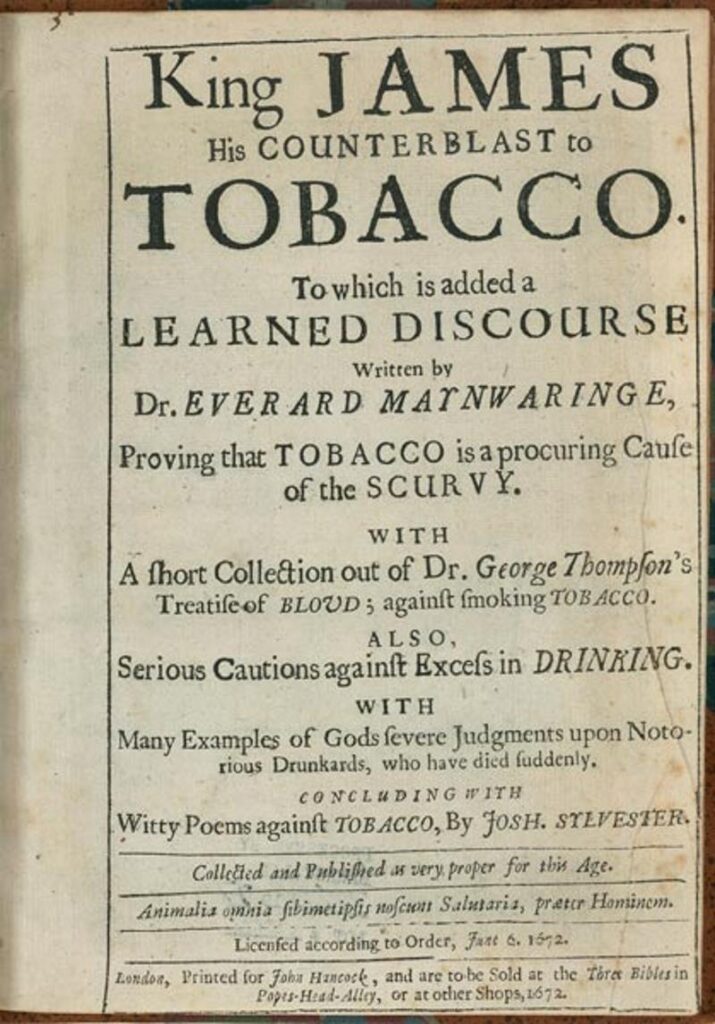

This is in large part because the use of hallucinogenic stimulants and other intoxicants short of alcohol was met with condemnation from both royal and church authorities alike and likened to witchcraft in an official decree against cannabis by Pope Innocent VIII in 1484. Any writer who risked mentioning it or any other outside source of inspiration likely had their work destroyed. At the time, Pope Urban VII even threatened with excommunication anyone who consumed tobacco in or near a church while King James I wrote an entire treatise against tobacco, implying that it may lead to sterility and possession by the devil. The original devil’s weed.

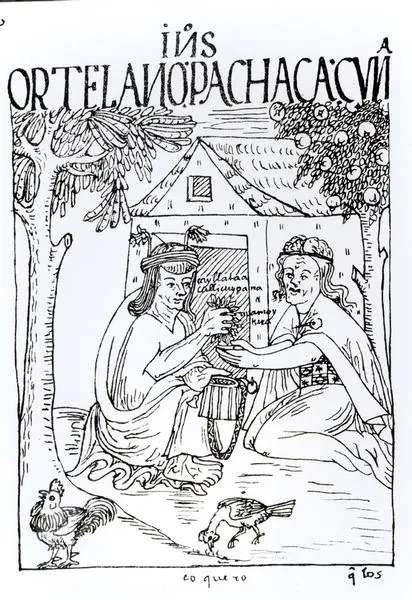

It’s suggested that coca leaves were brought over to England by the explorer Sir Francis Drake during his time in Peru (as early as 1573) while nicotiana leaves — from which we derive modern tobacco crop — arrived into mass consumption by way of Sir Walter Raleigh’s expeditions to Virginia between 1584–87 after Sir John Hawkins brought the first seeds to England in 1565. Being that these men were all contemporaries of Shakespeare, this gives a narrow window of roughly 32 years for both substances to have potentially reached Shakespeare before his death in 1616, but from here the trail becomes hazy. Four of the pipes with cannabis came from Shakespeare’s garden at his home of New Place, which he acquired in 1602. It may be a stretch, but given Shakespeare’s immense lifetime fame and royal connections, he may very well have had access to goods that were yet unavailable to the general public. Put that in your clay pipe and smoke it.

Following the publication of the study, titled Chemical analysis of residues from seventeenth-century clay pipes from Stratford-upon-Avon and environs, in 2001 and again in the July/August 2015 edition of The South African Journal of Science, Thackeray was quick to emphasize that there was no guarantee that any of the pipes belonged to the bard himself, adding that their time and place of origin were the strongest link, and given the prevalence of the crop in England at the time, Shakespeare would have been aware of its existence, at least. Certainly, even if the speculation is based on truth, there is no guarantee that some of these substances would have been imbibed purely for pleasure, as cannabis (alongside opium poppies) was a known home remedy in Elizabethan England.

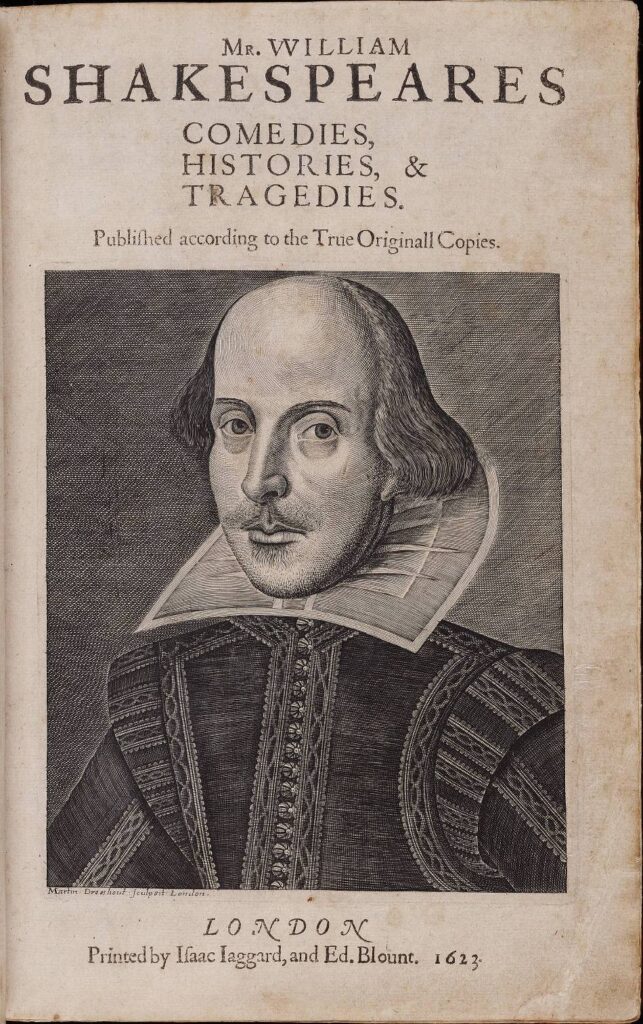

Cannabis sativa is said to have been introduced to England sometime during the Roman period and reached industrial-scale production during the Tudor era, becoming the nation’s second-most plant for cultivation following a mandate by King Henry VIII, according to Harvard Magazine. Although, it wasn’t for any kind of high. The plant was employed in the form of hemp for a variety of reasons including papermaking and canvas cloth as well as being twisted into rope (instead of joints), mostly for use on ships, due to their durability in resisting the effect of harsh seawater. After his death, Shakespeare’s First Folio was the world’s first attempt at collecting his works into a single book. Sure enough, the book was printed on hemp paper. Coincidence? A poetic one, certainly.

Notably, Sir Walter Raleigh is famously credited with introducing pipe smoking to Elizabethan England around July 27, 1586, after returning from the New World. Another key fact to take into account is that even though the infamous pipes were dated to the 17th century, a portion of Shakespeare’s birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon ( where several of the pipes were discovered) turned into an inn around 1647 named the Swan and Maidenhead. This is notable because exactly around this time, the English Civil War was raging and in response to the war and other turmoil, England saw a rise in drinking establishments where people went to relieve their stress. Who’s to say an errant customer didn’t light up a bowl of the stuff one night and drop their pipe amid a crossfaded haze? Given this information, there’s a likelier chance of that happening than the pipes having been in the possession of the famous playwright, seeing as he died early on in the century.

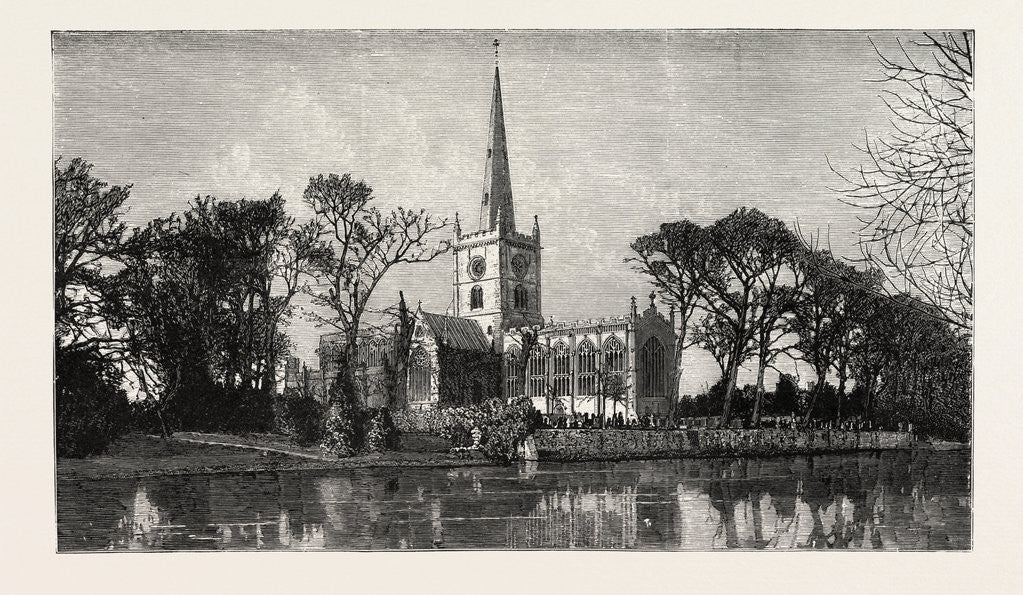

Nevertheless, the results set the media world aflame, and these small, inconvenient caveats didn’t stop the outlets from publishing a crop of intense clickbait proclamations that Shakespeare was definitely a raging stoner and chilled out with a fat bowl while creating some of the world’s best theatrical works. Riding on the buzz generated from his discoveries, Thackeray then set his sights on the earthly remains of Shakespeare, buried at the Church of the Holy Trinity in Stratford-upon-Avon on April 25, 1616. Again, the media lit up in response to the announcement.

Thackeray, now the director of the Institute for Human Evolution at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, is no stranger to picking through bones and assured that the technology is “non-destructive” and sufficiently state-of-the-art. “We have incredible techniques … we don’t intend to move the remains at all.” Thackeray said in a statement provided to FoxNews.

At the time, the plan was to examine Shakespeare’s teeth to check for signs that they may have clenched a clay pipe while also extracting a small DNA sample from his tooth enamel or any remaining tissue, hair, or nails that could expose his drug habits when put under chemical analysis. Thackeray also hopes to scan the bones of Shakespeare (as well as those of his his wife Anne Hathaway and daughter Susanna while he’s at it) and generate a digital reconstruction, in the hope that he could potentially discover the man’s cause of death and generate a facial reconstruction from his skull.

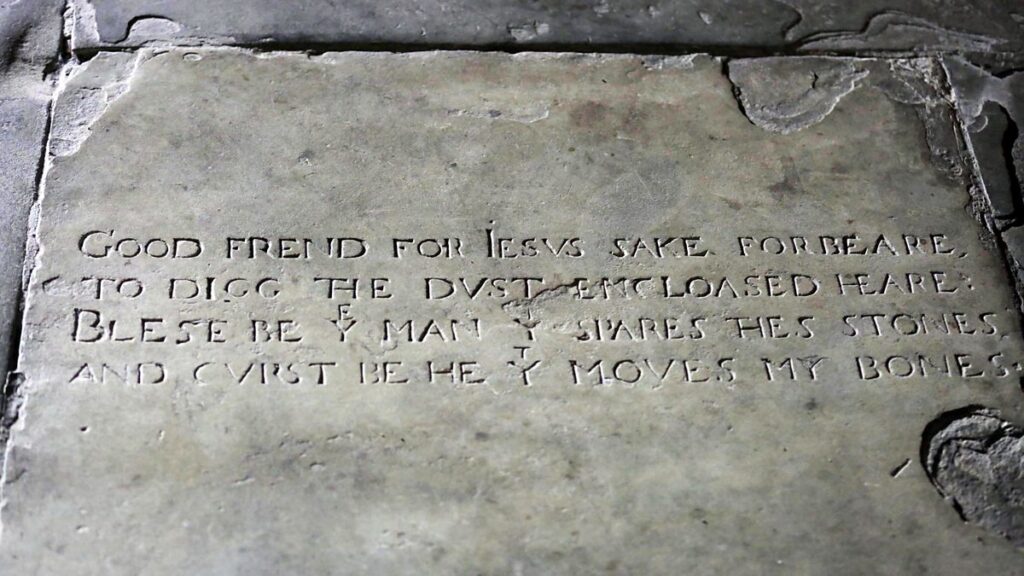

It all sounds well and good, except for the ‘underlying’ fact that Shakespeare had a deathly anxiety — phobia, even — of his bodily exhumation, he was even noted by Professor Philip Schwyzer of Exeter University to have included references to the abuse or exhumation of corpses throughout some 16 of his 37 known plays. As his final literary creation before his death, he wrote a curse which continues to stand above his tomb inside the church of his burial: “Good frend for Jesus sake forebeare,/ To digg the dust encloased heare;/ Bleste be the man that spares thes stones,/ And curst be he that moves my bones.”

Since this goes literally against the man’s final wish, this is likely the reason why there have never been any attempts to dig the man’s bones up anytime in the last four centuries, with the exception of an unfounded rumor that Shakespeare’s skull was stolen in 1769. But considering that some strange man from half the world away has come to chip off pieces of his teeth and upload his remains to cyberspace, one could say that in the end, the fears weren’t irrational at all. Thackeray, when asked about the curse, cleverly responded, “The curse said nothing about teeth.”

In 2011, Thackeray sent in a formal application to the Church of England to be given the go-ahead for the undertaking, the announcement was well publicized in the hope that some results would be compiled before the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in 2016. But media high wore off immediately after the church denied any existence of such a request, and it was only discovered several years later that the project took a hit when the request was denied by the Diocese of Worcester. Nevertheless, the question tempts: to see or not to see?

For interested parties, it was a buzz kill in the truest sense of the phrase. Shakespeare is enigmatic not only for his groundbreaking works of literature but also for the fact that such a perennially famous historical figure has entire gaps in his life unknown to modern history. Naturally, these gaps get filled with conspiracy and speculation of every degree, and judgment tends to become a bit clouded. Therefore, it makes sense that a 15-year effort to conclusively attach just one new fact about the man and his life would attract such widespread attention and such high hopes that the effort doesn’t go up in smoke. Seemingly once or twice a year, there’s a new report of revelations of new details or theories about the man. Usually, every time it happens, the world gets fired up about it until the information gets subjected to academic scrutiny.

Now, lack of physical proof notwithstanding, let’s delve into the man’s work and see the evidence there. First of all, throughout his entire body of work, Shakespeare has never made any direct references to tobacco, hallucinogens, or psychoactive substances. He did, however, make multiple references to intoxication by alcohol and various potions and poisons throughout his writing — even having been rumored to have died as a result of contracting a fever after a particularly serious night of birthday drinking, according to a disputed account of the man’s passing, written 45 years after the fact — as well as displaying a strong familiarity with herbs and their effects.

Romeo and Juliet mentions Romeo’s successful acquisition of illicit substances, punishable by death in the city of Mantua while in Othello, “drowsy syrups”, opium poppies, and mandrakes are invoked as inadequate remedies to the emotional manipulation foisted upon the play’s eponymous protagonist by the arch-villain of the story, Iago. In the latter example, Shakespeare specifically clarifies that he is aware of the psychoactive opium poppies imported from Asia and not merely the harmless, locally grown varieties.

Tentatively, the matter of an anonymous short play titled “A Country Controversy” is brought up and believed by some scholars (since 2015) to be written, at least in part, by Shakespeare. Performed for Queen Elizabeth on May 10, 1591, the play deals with an argument between a gardener and a molecatcher who lay claim to a jewel box dug up during the construction of a garden. Supposedly, the short performance was allegorical to the political intrigue of the time and was put on entirely to get on the queen’s good side, but that’s beside the point.

The good professor believes that this is indeed Shakespeare’s work, mostly backing up the claim through scholarly analyses that identify vocabulary similarities to works definitively known to be written by Shakespeare, primarily in the use of certain rare phrases. In the play, Thackeray points to a description of a particular plant in the garden. In the play, the plant is described as “that which maketh time wither with sondering”. “I suggest that this is a cryptic reference to cannabis, which is known to have the effect of making time ‘slow down’ — as perceived by a person smoking cannabis [or “wither]” he says. Certainly, it would be difficult to imagine what other plants could readily be associated with such a description.

Finally, Shakespeare’s sonnets are said to offer the clearest potential references to cannabis, and there are certainly several possibilities behind their meanings, but many of them are quite clearly half-baked. In Sonnet 27, Shakespeare references “a journey in my head,” while in Sonnet 38, he refers to a “tenth muse, ten times more in worth than those old nine which rhymers invocate”. While the first example was written in the context of dreaming after getting in bed after a tiring day of travel, the latter quote suggests that Shakespeare encountered something, either a new person, substance, or otherwise that was unlike any of the conventional sources of poetic inspiration.

Sonnet 118, a poem comparing the consumption and purging of food (and possibly other substances) with various romantic relationships in Shakespeare’s life begins with the lines “Like as to make our appetites more keen, With eager compounds we our palate urge.” To Thackeray, this is a potential allusion to the feeling of increased appetite under the influence of cannabis, or as some would call it, “the munchies”.

The most divisive example among the sonnets is certainly Sonnet 76, quoted earlier. While the believers of the Cannabis Shakespeare Conspiracy (Shakespearacy?) theory suggest “compounds strange” are referring to cocaine (with the word ‘compound’ known to be used as a chemical term as early as 1530) and the “noted weed” being, well, weed.

A more sober analysis suggests that the “compounds” are new literary techniques involving the creation of compound words, or even portmanteaus (such as ‘Shakespearacy’), which may have certainly sounded “strange” upon their initial encounter with readers. The “weed” is written off as a euphemism for clothing, a common literary choice at the time, being used in this context as a way of “dressing up” language to be more interesting, according to one scholar, adding that there is no clear evidence that the word “weed” was used as a name for cannabis or any other smoking substances until well into the 20th century.

Thackeray hits back, claiming that the entire poem refers to seeing the same words and literary conventions in a new light, the same way you’d start seeing anything differently when you’re high. However, Shakespeare, usually the dealer of potent verse, laments that he isn’t doing just that, leading his words to have a predictability to them in the eyes of the reader. Still, the scholars of Shakespeare who see him as a sober genius worthy of his own merit alone are ambivalent, even hostile, to Thackeray’s conclusions. His critics maintain he’s just blowing smoke.

In 2001, Professor Stanley Wells of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust reportedly called the whole thing “regrettable” while Professor James Shapiro of Columbia University described Thackeray’s reading of the sonnets as a “really lame interpretation” and that “Just because these pipes were found in his garden doesn’t mean his neighbor kid didn’t throw the pipes over the fence. There are a million possible explanations.” Harsh. Put that in your pipe and smoke it.

But could there be other evidence left undiscovered? Perhaps. It’s already been established that some plays not formally attributed to Shakespeare were written with his collaboration. But as with anything in the realm of conspiracies, if you go deep enough you’ll be sure to get some fascinating stories out of the deal, even if they’re far from true.

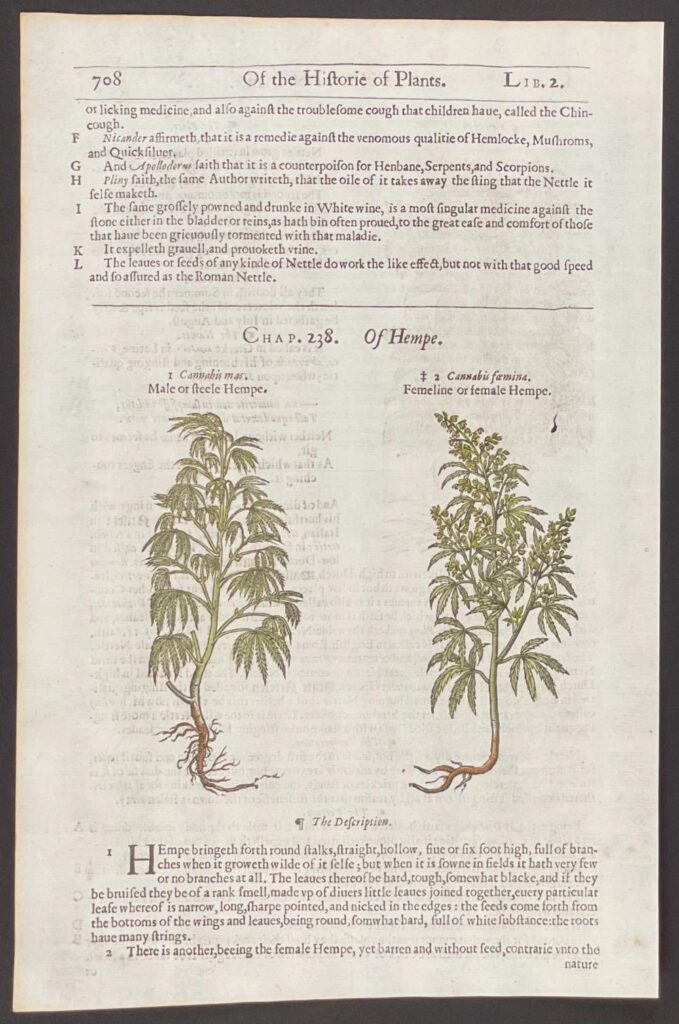

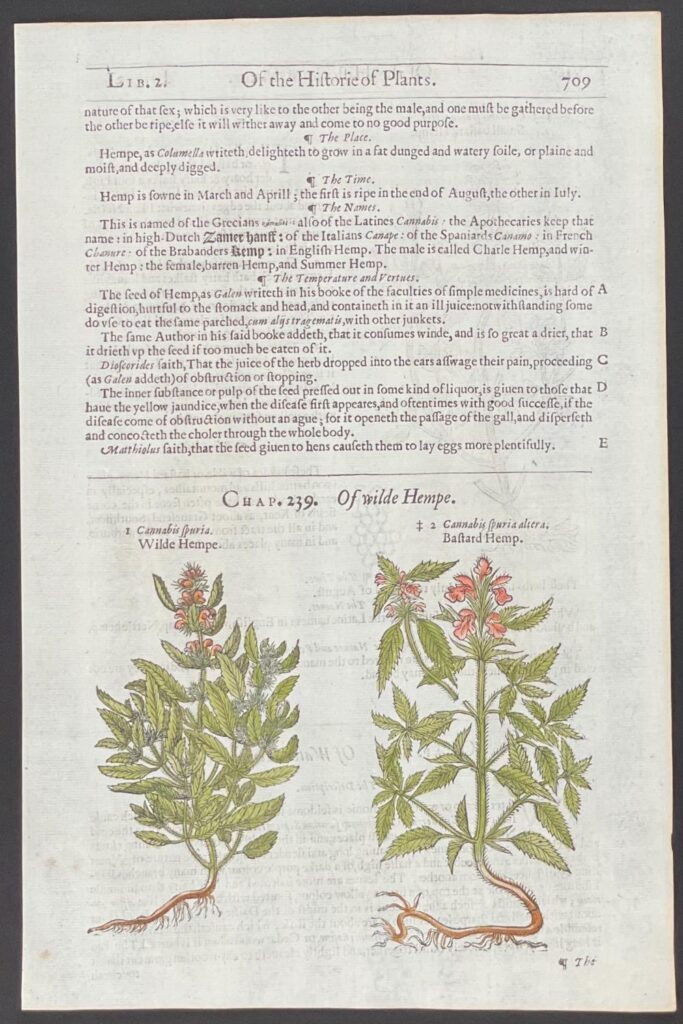

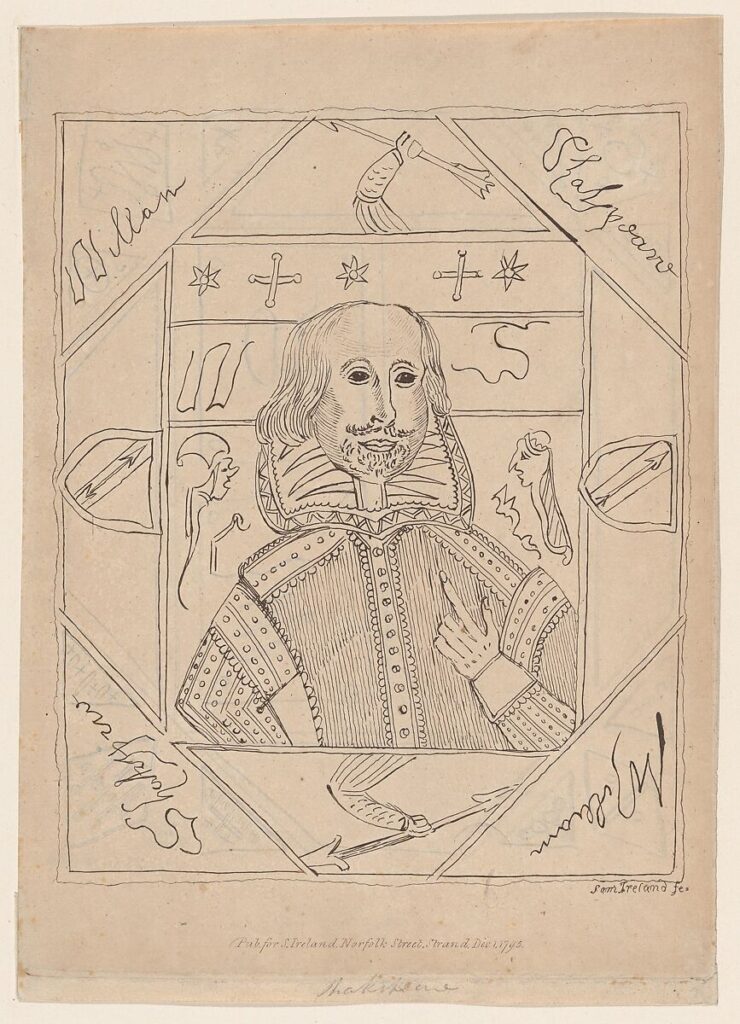

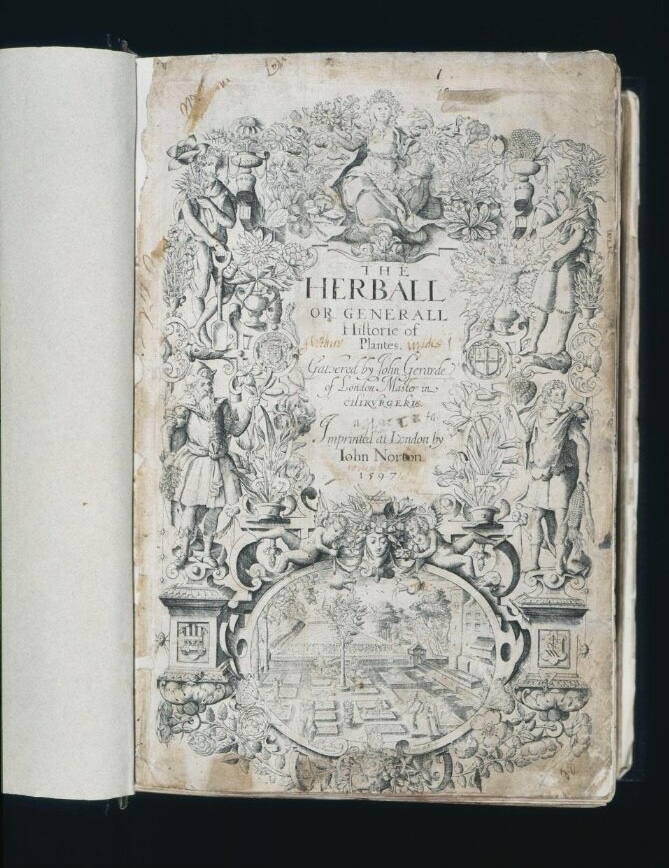

One deeply complex theory proposed by Mark Griffiths, a writer at Country Life magazine, was described by his editor as “the literary discovery of the century” and suggests that a book of plants published in 1597, John Gerard’s Generall Historie of Plantes contains the only known portrait of Shakespeare made in his lifetime on its cover, arguing his position through an interpretation of subtle symbolic elements around the engraving (the herbs, initials, motifs, etc.) such as the laurel wreath over the man’s head, suggested to be an allusion to Apollo, the Greek god of poetry and a common symbol for writers at the time.

Others were quick to nip the theory in the bud and point out that the man is actually Dioscorides, a Greek doctor who lived between 40–90 AD and published a book on herbal medicine that remained the standard across Europe for the next 1,500 years. For the doubters, he’s even labeled as such in a reprint of the same book with the same frontispiece engraving, but we’ll ignore that detail for now because there are other men on the cover as well, and this is where it begins to get delightfully conspiratorial.

William Cecil, otherwise known as Lord Burghley, was also identified as one of the men on the engraving. Cecil had his gardens tended to by the book’s author, Gerard, but was also the man who commissioned the performance of that anonymous play possibly written by Shakespeare, A Country Controversy, which was performed at his residence in Hertfordshire for Her Royal Majesty and her court. The play was set at the same aforementioned garden at Cecil’s Hertfordshire estate that was worked on by Gerard, who eventually wrote his book on herbs six years after the play’s performance and included entries for the herb, cannabis sativa, as well as the “tabaco or henbane of Peru” otherwise known as coca leaves, from which one derives cocaine.

Connecting the dots, this could mean that Queen Elizabeth, who was first in line to receive riches from the New World (courtesy of her favorite explorers such as Drake) and was also a visitor to Lord Burghley’s estate, brought along these exotic plants for Cecil’s extensive garden to be planted and studied by Gerard then potentially used for inspiration by the man behind the anonymous play, assumed to be Shakespeare. It seems less of a stretch considering that Shakespeare himself was favored enough by the queen to have his plays performed at her court on more than one occasion and probably received his own share of special privileges. But again, this is a reach, and it’s important to understand that the demand to prove this wild theory exceeds the evidence currently available.

Whatever the case may be, Thackeray remains adamant, “Literary analyses and chemical science can be mutually beneficial, bringing the arts and the sciences together to better understand Shakespeare and his contemporaries”, he explains to Time. Although it seems like every ounce of truth was being traded for a pound of sensationalism, the idea of keeping Shakespeare relevant to our times by any means possible is commendable, but we may just have to settle on appreciating the universal, lasting appeal of his plays alone and accept the blunt truth that Shakespeare was a mysteriously unique product of his time, even if his creative process may not have been the same as ours.

At a time when recreational cannabis use is becoming extremely popular, it seems more likely the entire effort to prove Shakespeare blazed it in the 17th century just like people do now tells us more about ourselves than of our predecessors, and we’re just looking at our reflection. Perhaps in the coming years, as research methods become more creative and sophisticated, we’ll be riding on a new high, but for now, it’s just smoke and mirrors.