A quarter of a century ago, a former Celtic punk musician started a performance of a song so absurdly long that it has still not finished playing. Measured against historical averages, it should still be playing centuries after most countries as we know them today will have ceased to exist.

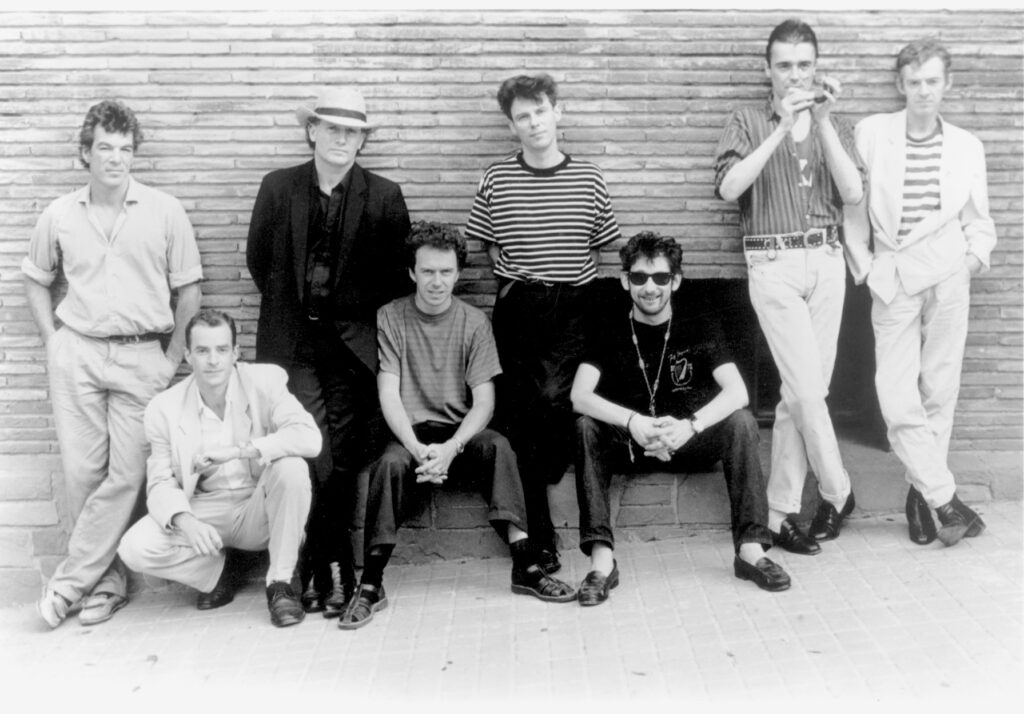

Jeremy Max “Jem” Finer is best known as a founding member and guitarist of The Pogues, the band that blended Irish traditional music with punk ferocity and poetic self-destruction. He recalled his years in the band and working with its frontman, “Shane [McGowan] could be maddening. He could take a few weeks to finally get around to doing something but once we got down to working he was always funny and inspiring and a generous collaborator.” Finer said.

“There was endless procrastination. But then, great focus,” he explained. The importance of patience in such a time and that oscillation between chaos and intense concentration, between delay and production, may have been, in hindsight, a rehearsal for what came next.

In 1995, while still touring with The Pogues, Finer had begun experimenting with different ways of composing music in real time. As the year 2000 approached, he found himself increasingly preoccupied with a much larger question: how to make sense of a millennium. How could one render sensible or tangible a span of time that is trivial in cosmic terms yet vastly exceeds any human life? How could attention be shifted away from the frenetic pace of late 20th-century culture toward something slower, deeper, and more expansive?

The problem was not musical at first. It concerned time as it is experienced and time as it is understood through philosophy, physics, and cosmology. At extremes of scale, time appeared baffling to Finer: fleeting and granular at the quantum level, yet unfathomably vast in geological and cosmological terms, where a human life is reduced to a barely perceptible blip.

That single idea immediately opened a flood of questions. How do you compose music that no one can ever hear in full? How do you account for changing cultural perceptions of sound that seem to become ever more rapid with each passing decade? Where do you place such a work? What technology do you trust to survive centuries? How do you plan for its survival across political, technological, and environmental upheaval? And most importantly: how do you ensure that people will come listen and want it to continue?

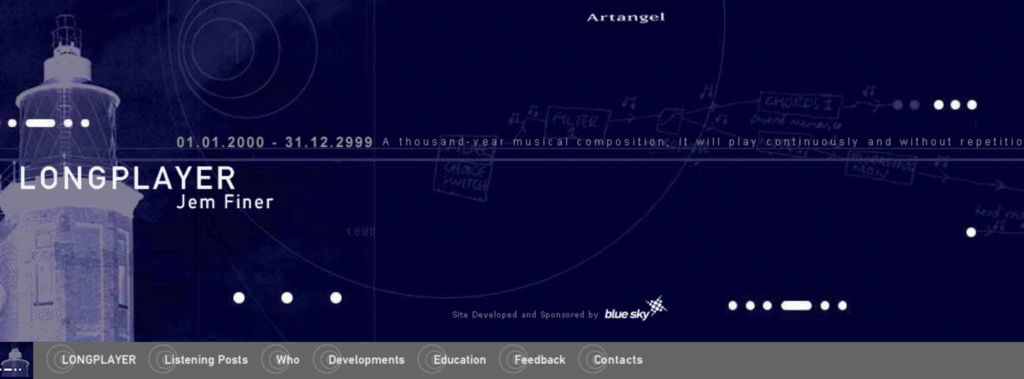

The work that emerged from these questions was Longplayer, a single audio piece conceived and composed by Jem Finer between October 1995 and December 1999 with the crucial support of Artangel, which commissioned and facilitated the project. The development of Longplayer was managed and guided by a think tank that included fellow musician Brian Eno, Director of Performing Arts & Head of Music at the British Council John Keiffer, landscape architect Georgina Livingston, Artangel co-director Michael Morris, digital sound artist Joel Ryan, architect and writer Paul Shepheard, and writer and composer David Toop.

Sound designers Ryan and Toop advised on acoustic properties and structural integrity, while extensive testing of algorithmic combinations was carried out to ensure that the system’s permutations would avoid repetition over centuries. Later, the audio was spatialized in collaboration with engineer Simon Hendry. A full account of this development was later published in the 2003 book Longplayer by Artangel.

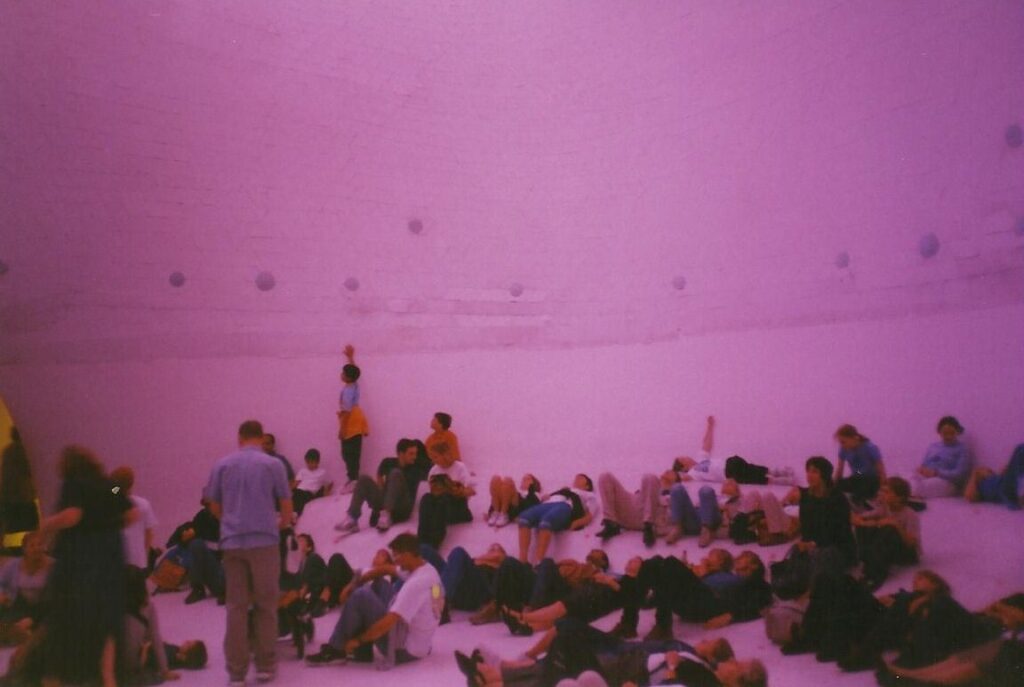

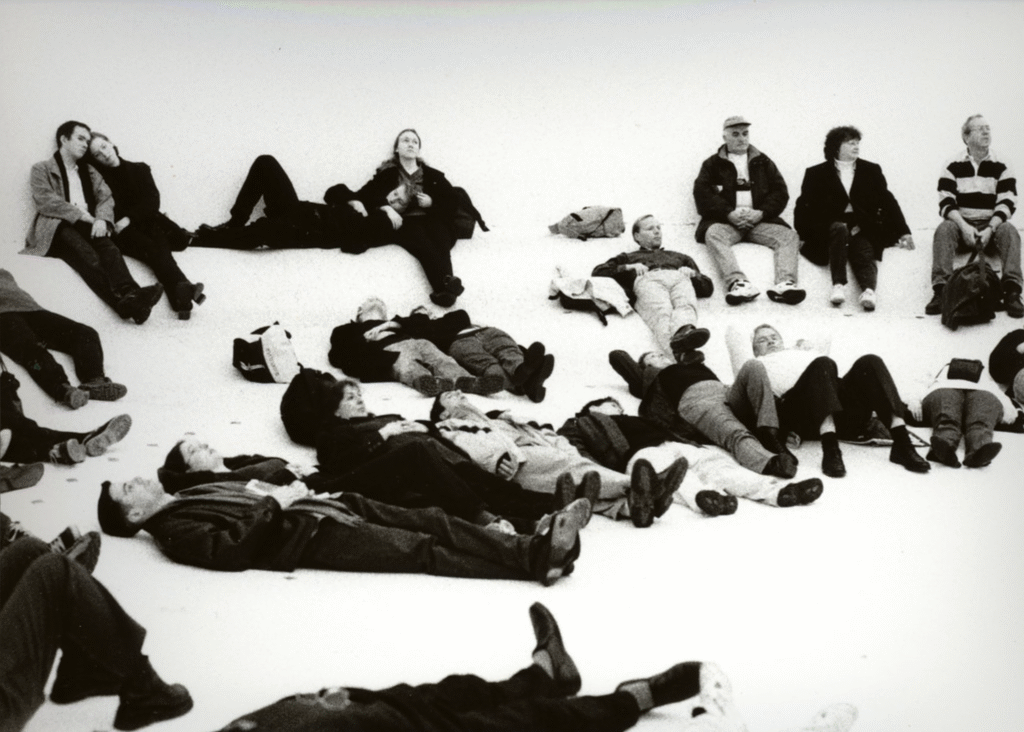

On January 1st, 2000, precisely at midnight, Longplayer began its performance by the Thames in the “relaxation zone” of the newly-constructed Millennium Dome (now the O2 Arena), a gaudy Blair-era assortment of exhibits and attractions celebrating the city and its entry into the new millennium. “My zone was full of all the people frazzled from the other zones,” Finer recalls. “It became the chill-out space.” Ironically, the Millennium Dome shut down just a year into its existence, having largely been considered a failure and facing numerous financial and management issues. As a result, Finer’s work was relocated across the river to Trinity Buoy Wharf, home of London’s only remaining lighthouse, an 1864 landmark once used by Michael Faraday for his experiments in optics and lighting.

Admitting the impermanence of any one location, Longplayer’s ultimate ambition exceeds any single physical site, or even a single medium, designed to persist whether London ends up underwater or reduced to a scorched imprint on the land. Adaptability is the core principle: “The score can be realized in different sources of energies and technologies, and in the revival of performances. It’s translatable into many different forms. There is always a means. You can even sing it. If there is nothing else left, there is our breath”

At the heart of Longplayer is what Finer calls the “source music”, lasting exactly 20 minutes and 20 seconds. This original composition was recorded in 1999 under Finer’s direction, performed by a small ensemble and designed specifically around the tonal qualities of Tibetan singing bowls. From this source, six related pieces were derived, each a harmonic transposition of the original: the original pitch, an octave below, seven semitones below, five semitones below, five semitones above, and seven semitones above. These six pieces are thematically linked, preserving harmonic unity while exhibiting distinct timbres and progressions. They function as the atomic units of the larger work and are segmented for recombination, with the stipulation that no piece is ever performed sequentially in full.

Longplayer operates according to simple but precise rules. “What you’re hearing,” Finer explains, “is a superimposition of six different sections. Each plays for two minutes, and then the start points move on. The amount each start point moves on is different for each of the six pieces.” Each of the six pieces advances through its length at a unique rate, ranging from once to 96,541 times per full cycle.

Because each layer moves at a different speed, the combined superimposition of these sections never repeats. There is no randomness involved whatsoever. The algorithm is entirely deterministic and mathematical, guaranteeing predictability while ensuring that no combination of layers will recur until exactly 1,000 years have elapsed. Only at the final moment of the year 2999 does the composition end, at which point Longplayer is planned to complete its cycle and begin again.

The Longplayer site explains the structure through a planetary metaphor. It asks you to imagine the solar system, with planets orbiting the sun at different speeds. Once in a very long while, they may all align, but it takes an enormous span of time before that configuration occurs again. “Longplayer is predetermined from beginning to end – its movements are calculable, but are occurring on a scale so vast as to be all but unknowable.”

The choice of Tibetan singing bowls as the sole sound source was central to the project. These bowls, standing bells made of metal alloys, have been in use for centuries and produce rich, resonant, harmonic tones. Most instruments drift out of tune over years or decades, but singing bowls are remarkably stable and durable. They are also easy to play, both by humans and by machines, making them ideal for a work intended to last for centuries.

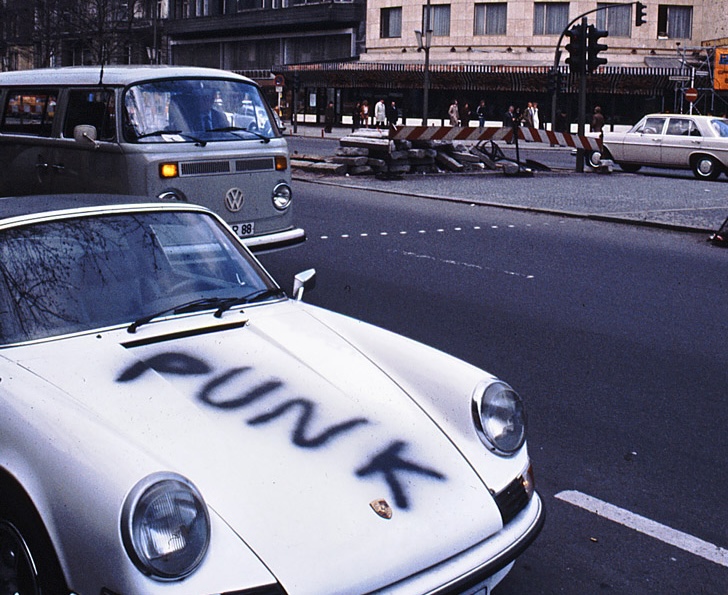

Finer, on the project’s website, has described them as a “bronze age solution to a new millennial challenge,” a choice that dignified the millennium rather than try to commodify it. Reflecting on the decision, he has noted that he unknowingly employed the same strategy he had used with The Pogues’ callback to traditional Celtic music: going back to something old and elementary in order to avoid sounding like a product of the time. “if we used sounds that were 1990s sounds,” he has said, “they would have immediately sound dated.”

Longplayer will continue without repetition until the last moment of 2999. It initially ran as a recording on a single Apple iMac, which was sufficient to start the piece but never intended as a long-term solution. Finer was acutely aware that personal computers, operating systems, and storage media are transient. Over time, the system has been migrated to more robust and transparent technologies, as well as other, non-digital mediums.

Today, Longplayer’s source material runs in the SuperCollider programming language on Raspberry Pi hardware, chosen for its simplicity, reliability, and ease of replacement. Yet from the earliest stages of the project, it was clear that Longplayer could not depend solely on digital technology if it was to survive for centuries. Mechanical, non-electrical, and human-operated versions have been considered and employed as accompaniments to the performance.

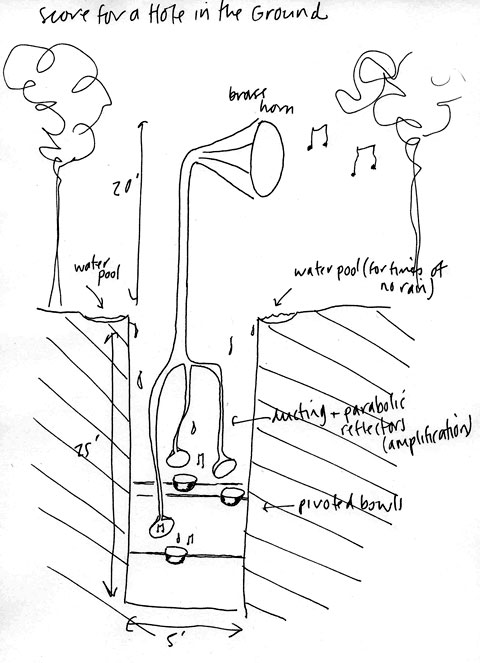

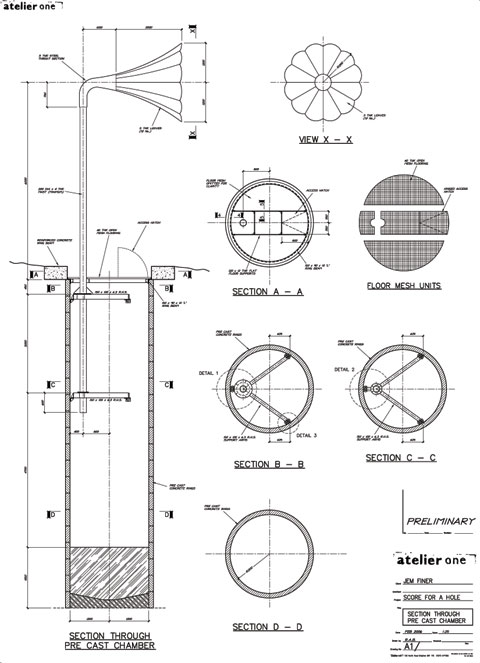

Finer’s wider artistic practice, spanning installations, film, photography, and music, has long focused on the broadness of time and space. In July 2005, Jem Finer won a PRS Foundation New Music Award for a proposal that treated weather itself as a compositional force. The work, titled Score for a Hole in the Ground, imagined a landscape riddled with vertical voids: wells, mine shafts, fissures, bunkers, culminating in a deep shaft fitted with instruments suspended at different heights: bowls of varying sizes and tunings, each pivoted delicately on its center of gravity. Falling water became the performers, striking the bowls like bells; as they slowly filled, their timbres shifted and their slight swaying modulated the sound, before overflowing into vessels below. The resulting music was carried upward through a tube to a brass horn rising twenty feet above the ground, amplifying the subterranean activity while doubling as a sculptural landmark from above. Mechanically, it’s not unlike the bamboo tube of a suikinkutsu, a decorative music device usually installed in traditional Japanese gardens. The piece was realized in King’s Wood near Challock, Kent, and installed over the summer of 2006.

In March 2012, Finer launched Mobile Sinfonia, a global composition distributed as mobile phone ringtones, intended to function as a sound piece on a global scale, performed in tandem by anyone who installed the ringtones to their phone. Developed during a year as a non-resident artist at the University of Bath, the work explored the mutual invasion of soundscapes as thousands of phones collectively formed a dispersed, continually reactivated piece of music. Finer later received an honorary doctorate from the university. He continues to develop projects that reflect his interest in the intersections of music, science, long-term sustainability, and the repurposing of older technologies, including Spiegelei, a spherical camera obscura using his own 360-degree projection system, and Supercomputer in Cambridge, a five-bit mechanical sculpture designed to compute minimal musical scores using marbles.

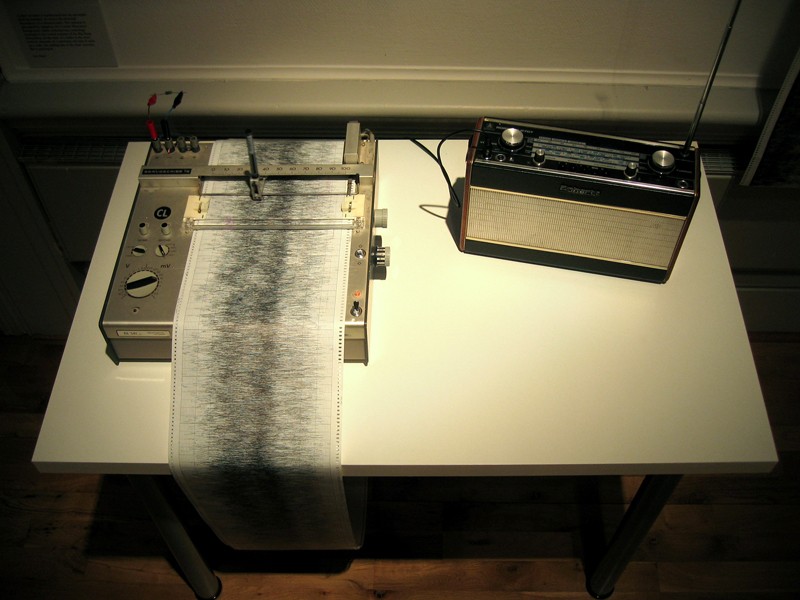

Other works push this logic of unlikely systems even further: a chart recorder repurposed as an automatic drawing machine driven by the electrical fluctuations of a detuned radio, in collaboration with friend and artist Ansuman Biswas, Finer has also staged more improbable interventions, including a project in which they dressed as genies and floated in zero gravity aboard a plane at the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center near Moscow. The goal? Conceived on a “shoestring budget, mental discipline, and Russian hospitality”, the project set out to “defy gravity and military-industrial economics to celebrate the dream within us all.”

With Longplayer, the attention turns to both the processes of statistical computation and human participation, as if the project was taking on an intelligence of its own. As Finer explains on the official website, “Longplayer grew out of a conceptual concern with problems of representing and understanding the fluidity and expansiveness of time. While it found form as a musical composition, it can also be understood as a living, 1000-year-long process – an artificial life form programmed to seek its own survival strategies. More than a piece of music, Longplayer is a social organism, depending on people – and the communication between people – for its continuation, and existing as a community of listeners across centuries.”

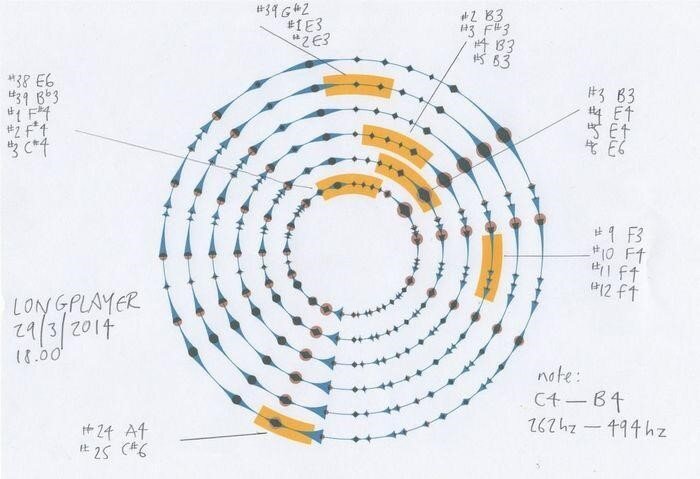

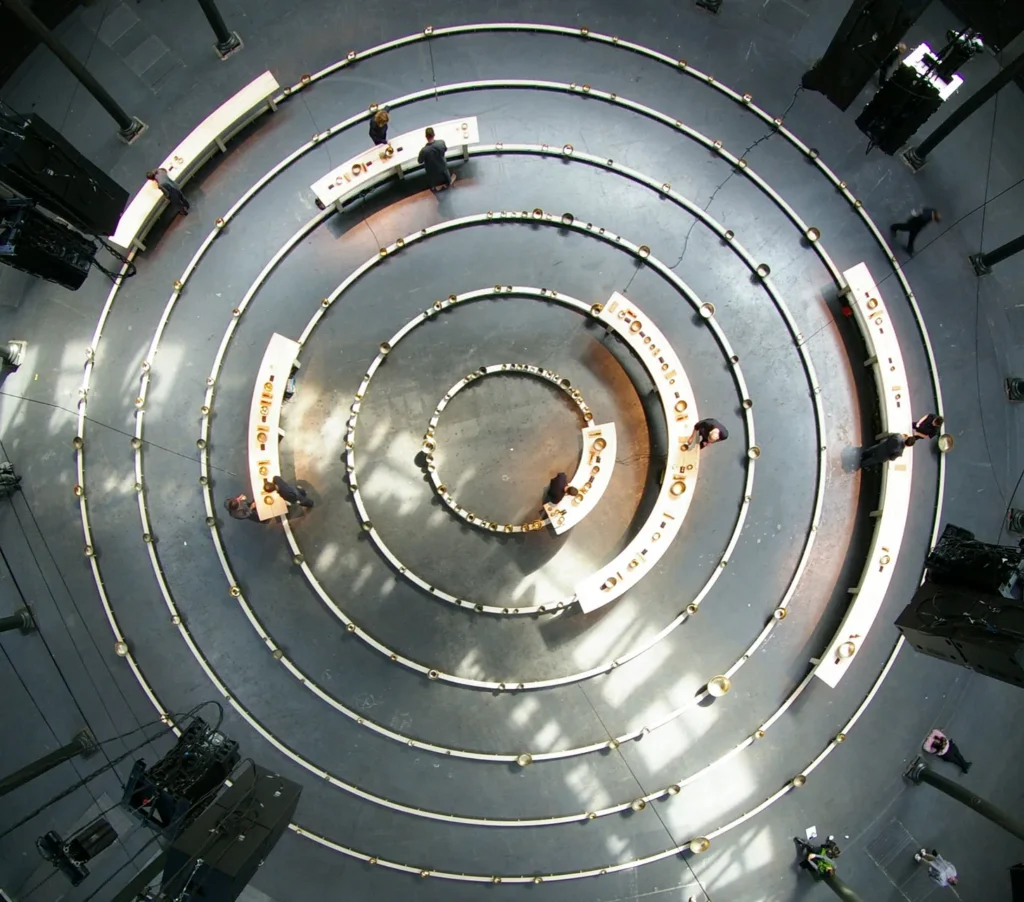

One of the key insights behind Longplayer is that, because it is generated by a mathematical construct rather than a fixed recording, any part of the piece can be performed live, in perfect synchrony with the ongoing work. In 2002, Finer developed a graphical score for Longplayer, arranged for 234 Tibetan singing bowls and six players. The score proposes a configuration of six concentric rings of bowls, representing the six simultaneous transpositions of the source music. Using this score, performers can realize sections of Longplayer acoustically, without electronic intervention. In this form, the project now had a means to make its way outside of the bounds of Trinity Buoy Wharf.

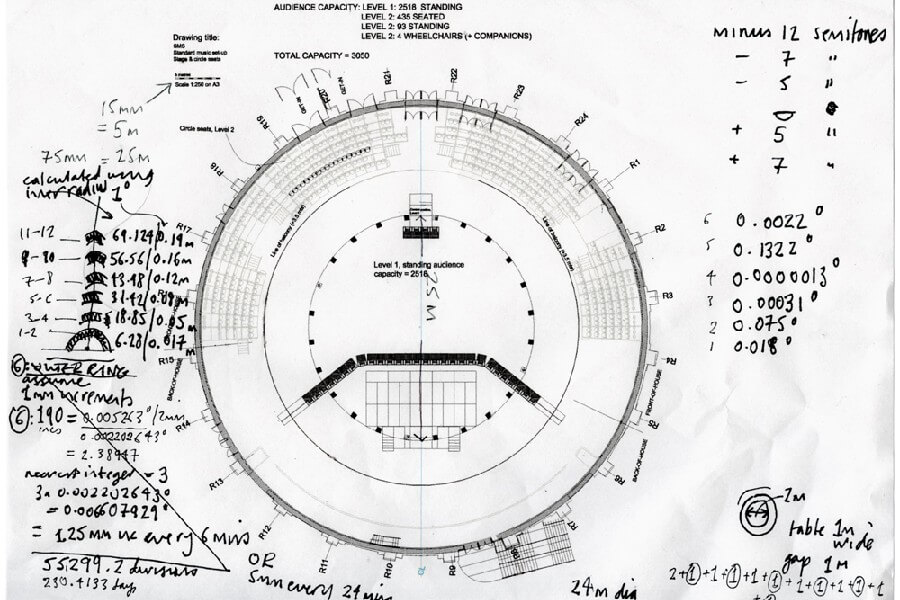

This opportunity has since been realized many times. Having just spent two years as an artist in residence at the Astrophysics Department in Cambridge, Finer directed Longplayer’s first spectacular live performance in 2009: a 1,000-minute section drawn from its vast continuum, performed by an orchestra of 26 performers using 32 precisely tuned Tibetan bowls at the Camden Roundhouse, a large circular hall fit for the project’s unique arrangement, which, taken as a whole, assumes the form of a purpose-built 20-meter wide instrument, “a giant synthesizer built of bronze-age technology,” as Finer described it.

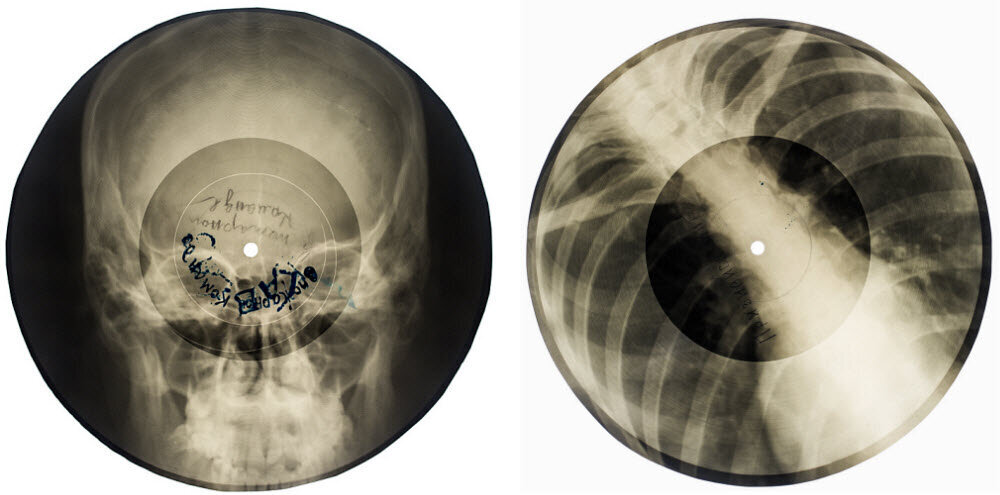

Further live performances followed, including a semi-circular rendition at Trinity Buoy Wharf on News Years Eve of that same year to mark the project’s tenth anniversary, and a performance at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco in 2010 in collaboration with Brian Eno’s Long Now Foundation. In 2014, Longplayer was performed by a coalition of voice choirs as part of ongoing experiments to free the work from dependence on technology. A version for 500 voices was realized in 2018, and the piece has also been considered for transfer to 12 specially pressed records played on 12 record decks, to be performed through a new format.

The performances regularly continue to this day. As recently as April of last year, another 1,000-minute section of Longplayer was performed live at the Roundhouse, uninterrupted, from 7:20am to midnight, precisely as written for that time and date. Finer has explained that while Tibetan bowls can be struck, they are more interestingly played by running a wooden beater around the rim, like rubbing a finger around a wine glass, drawing out sustained tones.

Longplayer is generally acknowledged to be the longest single piece of music ever conceived. By sheer length alone, it surpasses John Cage’s 639-year-long As Slow As Possible, currently playing in the church of St Burchardi in Halberstadt, Germany. It dwarfs Wagner’s Ring Cycle, which runs for a mere 15 hours, and makes even Bull of Heaven’s day-length songs seem comically brief. As if you needed further perspective, The Caretaker’s 6‑hour long album Everywhere at the End of Time is just 0.0000685% of Longplayer’s 1,000 years.

Yet Finer has repeatedly insisted that the music itself is not the point. As he explains, “[Longplayer] grew out of a lifelong curiosity about time and its dimensions, traced back to temporally vertiginous childhood encounters with starlight and ancient stones and the ebb and flow of time before clocks. For me it’s more about creating a space to dream one’s way into long flows of time, an experiment in ‘making’ time. But everyone has their own take on it — which is as it should be.” Thus, as with John Cage’s composition, the project serves as an exploration of the concept of “deep time”, first introduced by writer John McPhee in his 1981 book Basin and Range, where he explores the field of geology and ancient terrain from around the world.

McPhee used the idea of deep time as a way of grasping the almost incomprehensible age and scale of the Earth. Deep time stretches far beyond human history, beyond civilizations, languages, even species, into spans of millions and billions of years in which continents drift, mountains rise and erode, and oceans appear and vanish. McPhee’s intent was to translate deep time into something mentally survivable, often by compressing Earth’s history into metaphors like a single calendar year or a long scroll unrolling beneath your feet. Nevertheless, the effect is quietly destabilizing: human time becomes a thin, fragile surface layer atop an almost infinite geological past.

Longplayer can now be heard at listening posts around the world, including the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, the Orangery in Nottinghamshire, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Egypt, and the Long Now Foundation’s cafe and museum at Fort Mason in San Francisco, the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in West Bretton (established in 2016), and the Brisbane Powerhouse in Queensland, Australia. In total, there are around ten permanent listening posts worldwide, located in places where the sound integrates with its environment.

Selected excerpts of the piece, have also been released as separate albums on the project’s official Bandcamp page. The work can also be heard live via a internet stream, as well as through a paid app available from the Apple Store. Released in 2015, the app visualizes the rules of Longplayer using concentric loops. Yellow bars indicate what is currently playing, brown circles represent the 39 Tibetan singing bowls initially recorded for the composition, and blue waveforms show volume. The app performs the music in real time by acting on recordings of the bowls without requiring a constant internet connection. All instances of Longplayer remain synchronized through reference to the current time and date. As long as the phone survives, Longplayer survives with it.

One of the earliest proposed forms for Longplayer imagined a purpose-built, self-sufficient chip designed to play the piece and nothing else: cheap enough to be manufactured by the million and scattered across the world “like seeds blown from plants,” a deliberately biological strategy for achieving large-scale redundancy. In this sense, the app represents a belated realization of that idea, with Apple and its contemporaries supplying the digital seeds and Longplayer quietly riding the coattails of the near-ubiquity of the devices they have already dispersed across the planet.

Alongside its musical life, Longplayer has become a catalyst for long-term thinking across disciplines, inviting thinkers and collaborators from a broad range of field. Since it began, it has exercised minds in architecture, engineering, landscape gardening, artificial life, quantum mechanics, communications technology, and comparative religion. It has influenced the broader landscape of long-term art projects and is a founding participant in the informal Long Term Art Projects association, established in late 2022, alongside initiatives such as Katie Paterson’s Future Library in Oslo as well as the Long Now Foundation, which is currently working on an underground clock designed to independently keep time for 10,000 years.

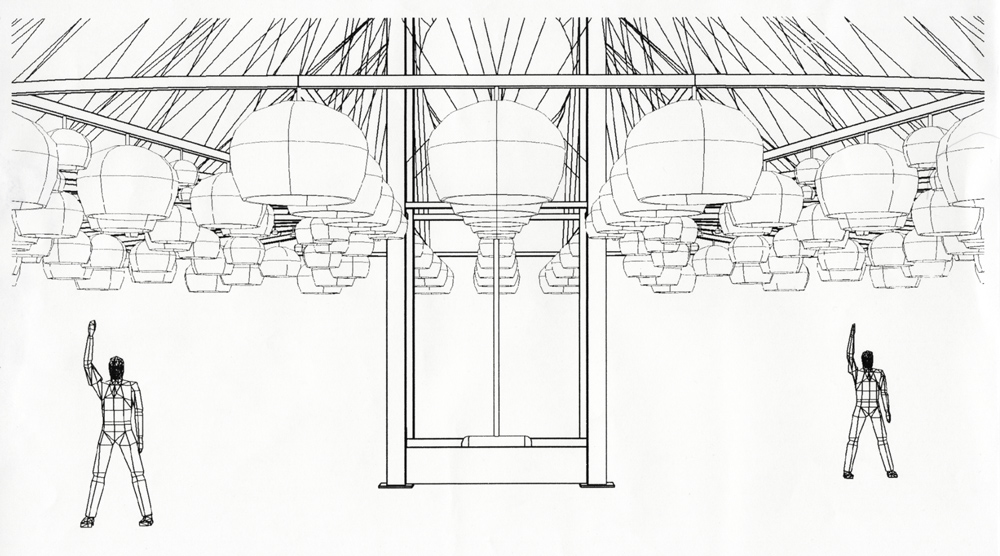

In addition to phone apps, the Longplayer Trust has also explored alternative playback methods, including analog devices, radio transmission, and constant human performance, to mitigate the risks of hardware degradation. One mechanical model under investigation is based on the record-player concept: six two-armed turntables, each six to twelve feet in diameter, capable of raising, lowering, and advancing arms with extreme precision. The recordings would then be printed on large vinyl records and selectively played.

Another of these experimental methods, and probably the most unique, is Sonic Ray, a project that beams the sound of Longplayer across the Thames as encoded light. Finer learned that sound can be transmitted as light, then decoded back into sound at its destination. “What could be better than to relight the lighthouse with a beam that actually carries Longplayer?” he asked. The installation sends the music 800 meters across the river to Richard Wilson’s cross-sectioned ship sculpture, A Slice of Reality, in Greenwich. Looking towards the long future, the Trust envisions a potential Longplayer Day, occurring annually on the 21st of June, the longest day of the year, featuring live performances of the piece across the world.

The strategies are both creative and as a means of survival, as it costs about £100 per day to maintain keep the performance going. The “Buying Time” program allows individuals to sponsor a day of particular significance for that very same amount. In return, Finer sends a signed Longplayer score from that date, and sponsors are invited to display a personal object in the Buying Time Cabinet at the lighthouse. Likewise, supporters have sponsored individual bowls that make up the project, with donation sizes increasing in relation to the size of the bowl. In return, various phrases of the sponsor’s choosing are engraved on the side.

In many ways, personal memorials and testimonies have also become part of Longplayer’s evolving history. Oshin, a live performer of the piece and the 19-year-old son of Ansuman Biswas, now the reclusive conductor of Longplayer Live and a Longplayer Trustee, has grown up with the work. “It’s always been a soundtrack to my life,” he has said. “For me, it’s the sound of everything.” Playing the piece that had begun its performance years before he was born was, for him, profoundly moving. Ansuman himself has reflected on how, over 26 years, Longplayer has begun to accrue a past as well as a future, with generations coming and going while the work continues. While children of the project’s original creators have grown up and become participants in the project themselves, some of the original creators have since passed away.

On one occasion, Ansuman Biswas performed an eight-hour section of Longplayer at Trinity Buoy Wharf, a “one millionth” fraction of the piece’s total length. Drawing on principles of Dhrupad and Nada Yoga: Swara (tuning oneself to the environment), Samaya (the resonance of a particular moment), and Raga (specific patterns of notes or tones that evoke states of mind), Biswas calibrated a tanpura, a traditional instrument from the Indian subcontinent, against the background drone of Longplayer, itself set against the cosmic background. He described the performance as “surfing on a constantly unfolding wavefront, riding all the currents.”

Longplayer’s philosophy extends into conversations as well as performances. As part of its yearly program, a series of conversations is organized, featuring speakers ranging from 87-year-old historian and philosopher Theodore Zeldin to broadcaster and biologist David Attenborough. The program has invited climate activists, physicists, epidemiologists, writers, and archaeologists, among others. There is no formula beyond the stipulation of duration (1,000 minutes for the entire event, naturally) and a shared set of questions and discussions regarding where participants see the future is heading, and what their experiences have led them to believe can be done about it.

A further series involved a series of chain letters sent from one thinker to another, encouraging an ongoing conversation always added to by a new individual. Recipients and writers included Brian Eno, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, and Alan Moore. Notably, there are no politicians involved in any of the conversations, as a rule. As Artangel’s Michael Morris has said, “quite a lot of the problems we’re facing in so many different fields are to do with the short-term values of politics. Most of the creative and imaginative thinking about the future is being done outside that system.”

Throughout all of this, Finer has returned to a core conviction: Longplayer is not a passive artwork but a challenge, a quest that requires care across generations. In this light, the project is not so unusual as there are many historical examples from of similar undertakings. In the Zoroastrian religion, adherents maintain temples containing flames that are kept perpetually kept alight, never going out for centuries. The Ise Shrine in Japan is periodically dismantled and rebuilt to preserve both craft knowledge and an understanding of impermanence. The Queshuachaca in Peru, the world’s last remaining Inca rope bridge, is rebuilt every year to maintain its sturdiness. Such practices may seem inessential, but they are centuries-old examples of where knowledge and continuity survives through collective responsibility.

“If nobody is interested, or there is no way of playing it, it will no longer exist,” Finer has said. “But so far, so good.” Over a quarter of a century on, Longplayer still rings out from the lighthouse, streams across the internet, plays itself on phones, and sounds from listening posts around the world. As Finer puts it, it now has a history as well as a future. And if all technologies fail, if all machines fall silent, the score can still be sung. “If there is nothing else left,” he says, “there is our breath.”

Beyond looking ahead to the eventual day the Longplayer concludes its initial performance, the Longplayer Trust have made the effort to look at least as far back in time as well. Last year, members of the Trust paid a visit to Exeter Cathedral, founded around 1050 AD and home to the 10th-century Exeter Book, a UNESCO-recognised cornerstone of English literature. Here, the two institutions joined forces and a “brief” 1,000 minute transmission of the Longplayer echoed through the halls of the cathedral. Following the visit, the Trust’s chair, Sam Kinchin-Smith, shared a translation of Old English gnomic verses from the Exeter Book that seem to ring uncannily true: “The sound unstill / the deep dead wave / is darkest longest.”