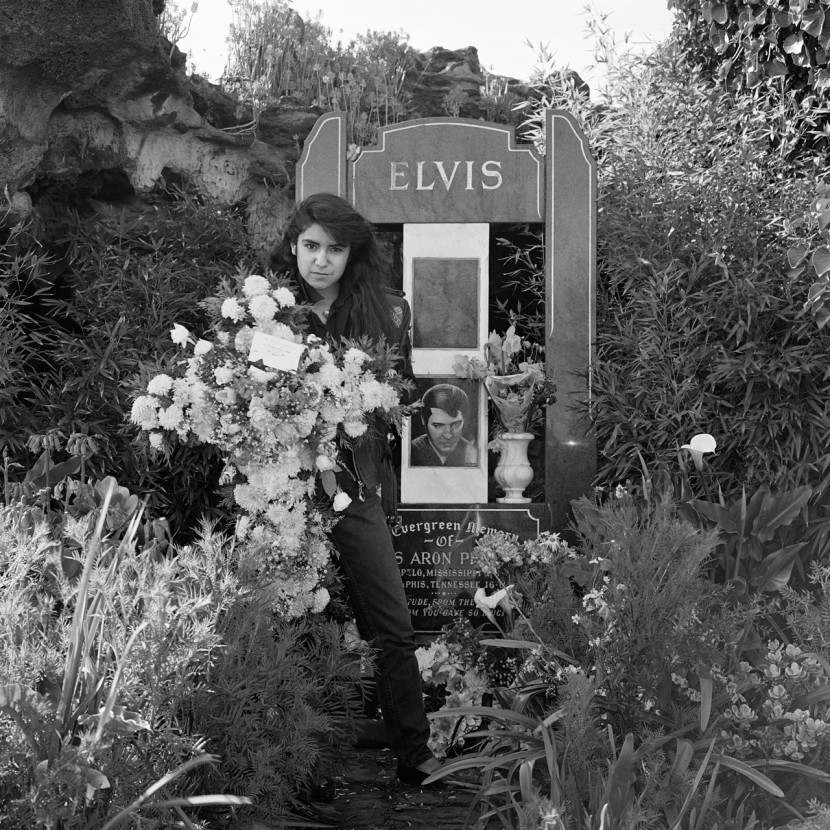

Each year on August 16, Elvis fans gather at a Melbourne cemetery on the anniversary of his death, observing the date with regularity and ceremony. One local photographer documented the event over 15 years.

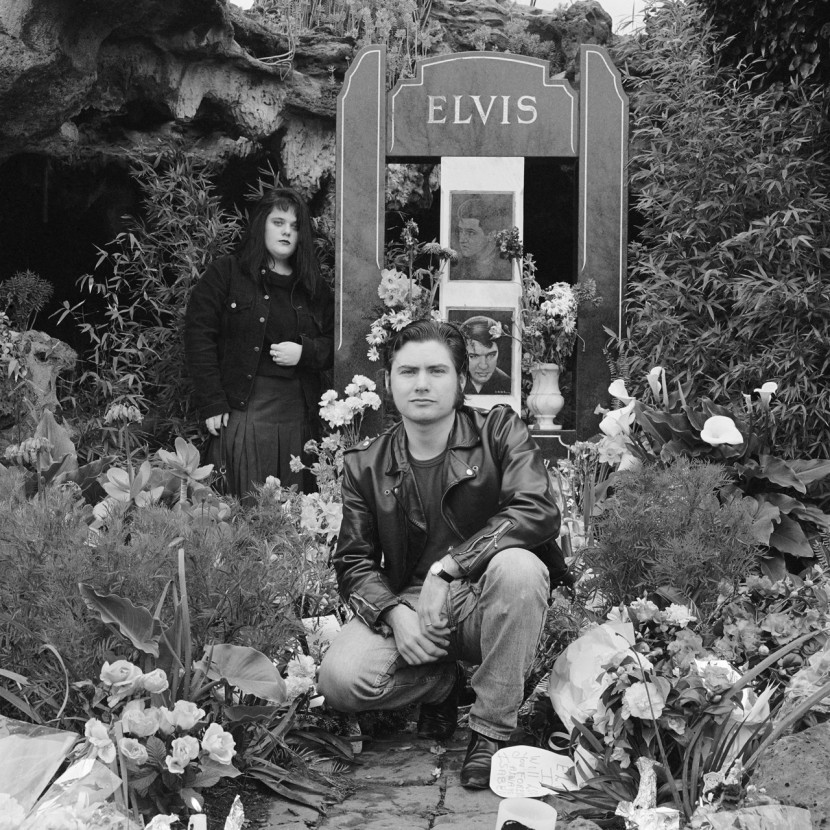

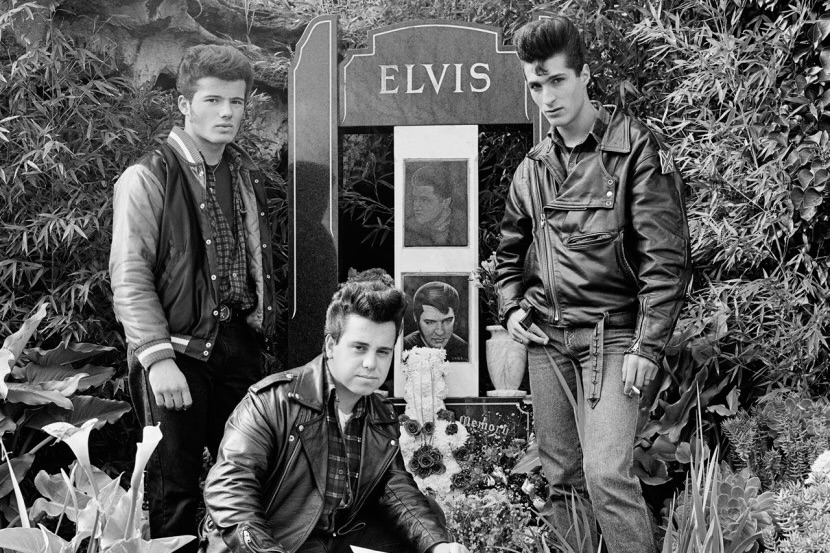

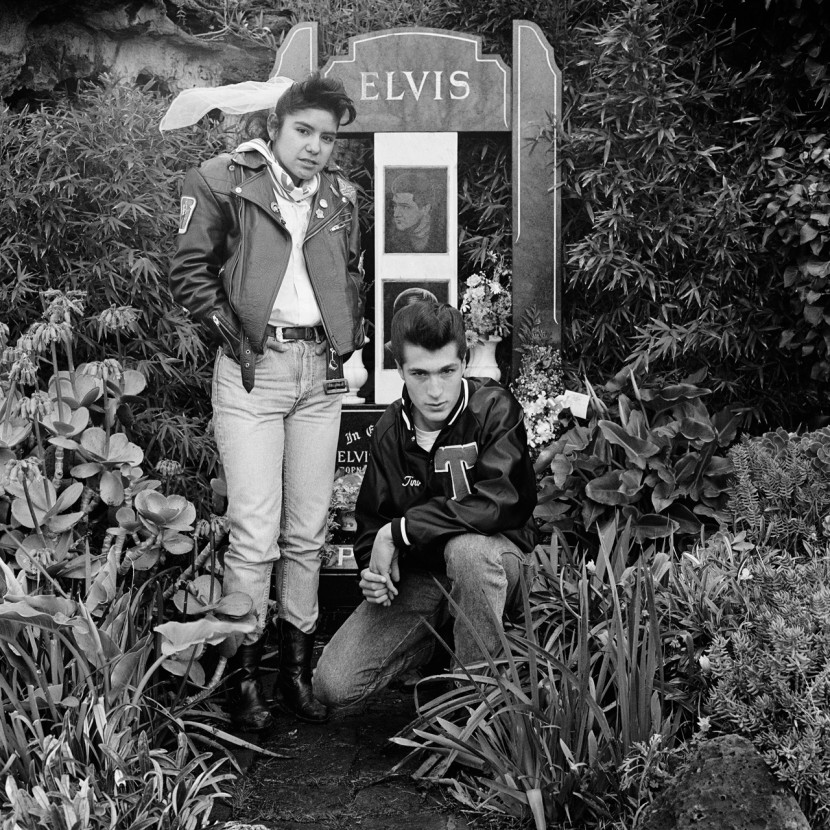

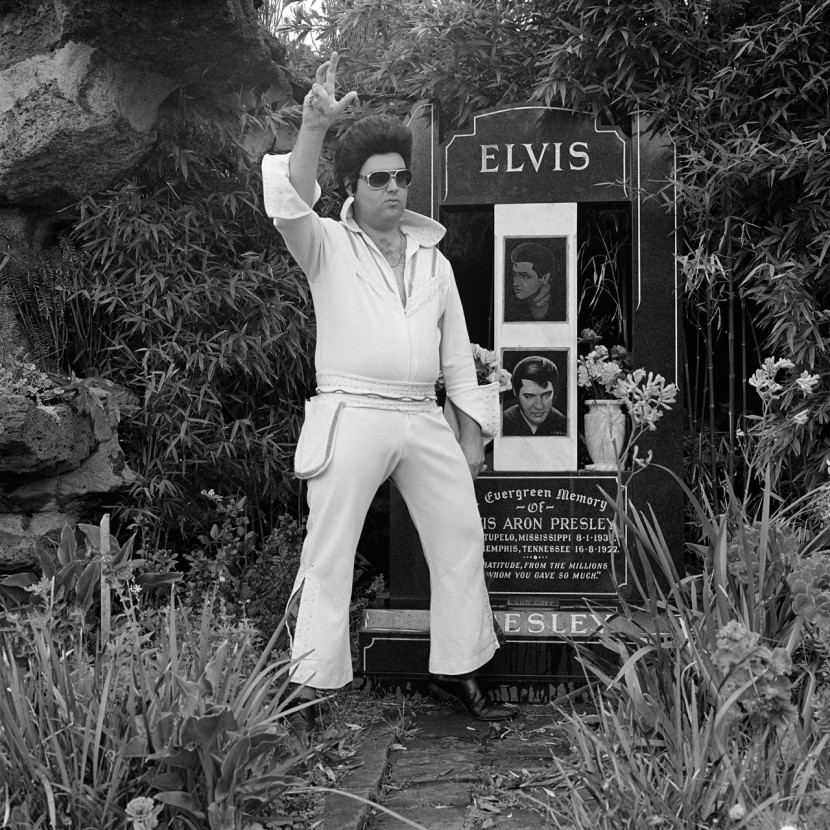

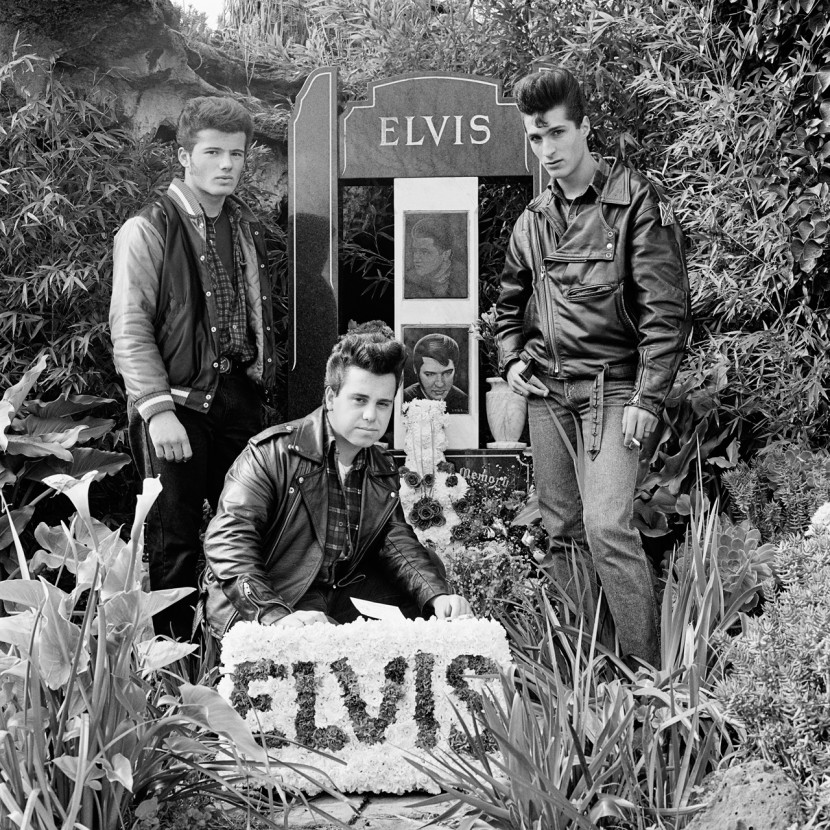

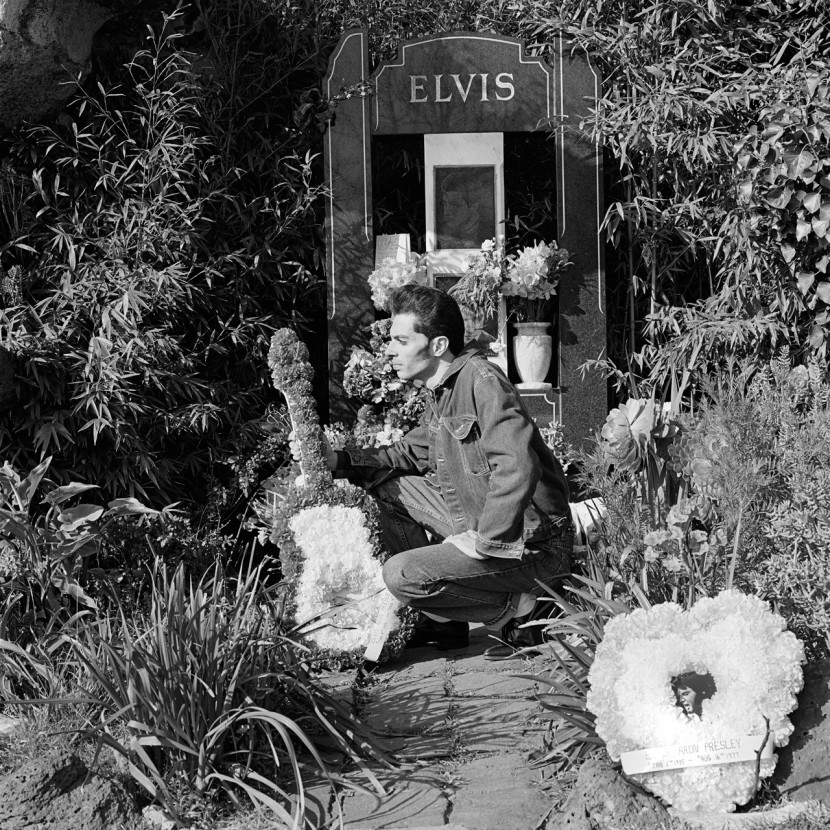

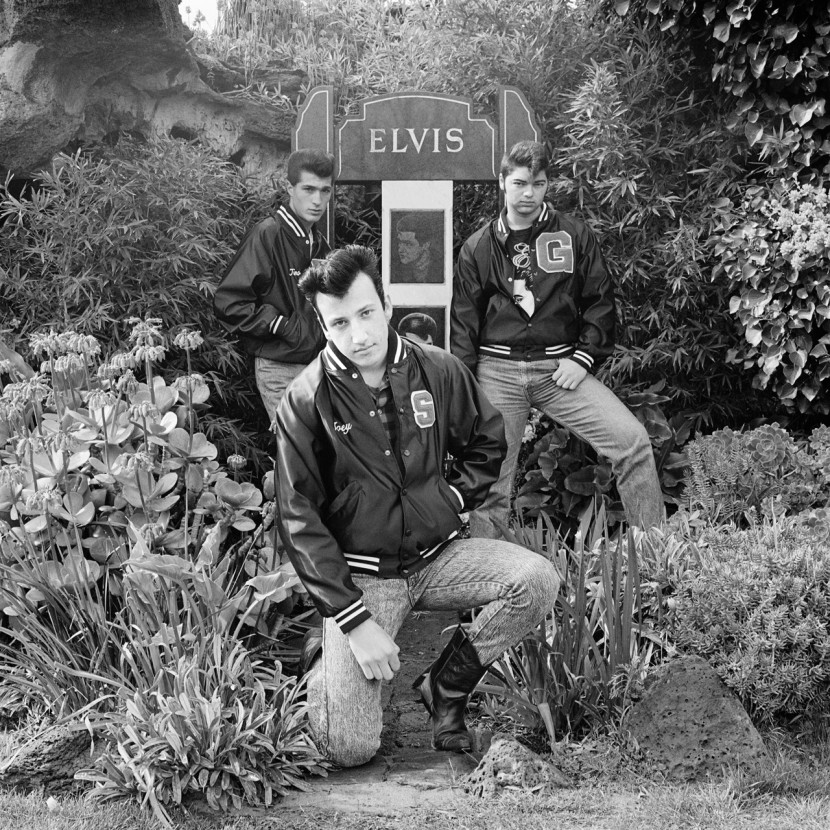

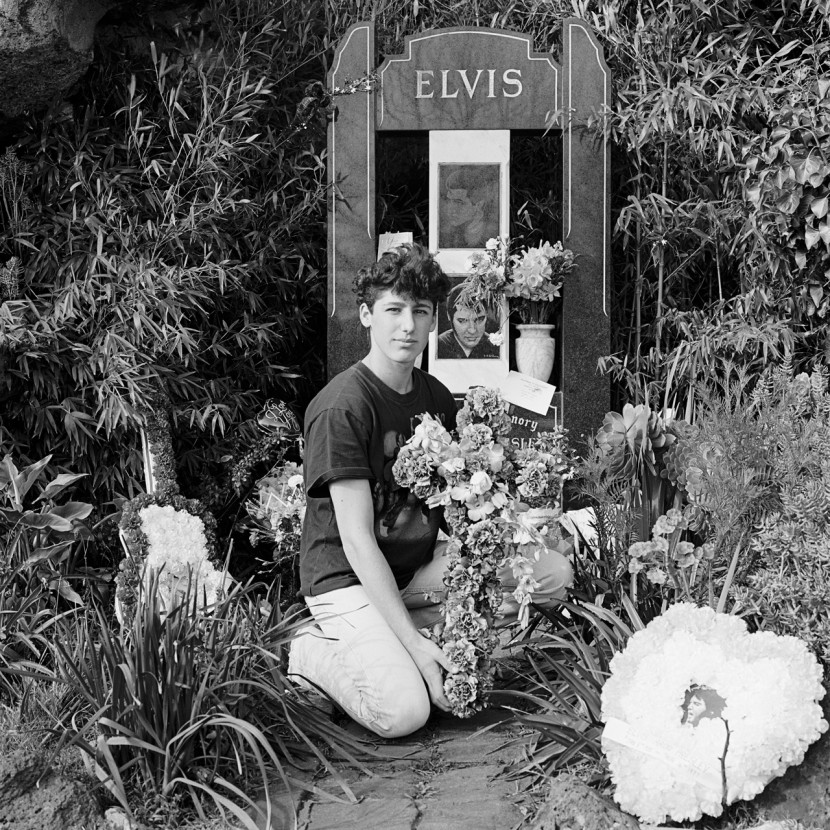

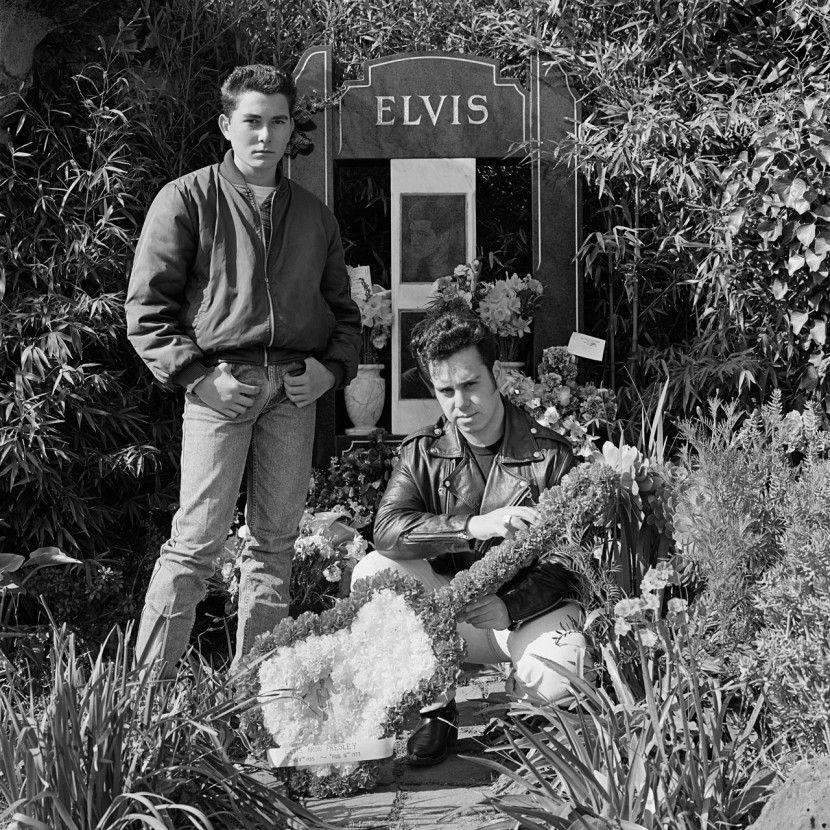

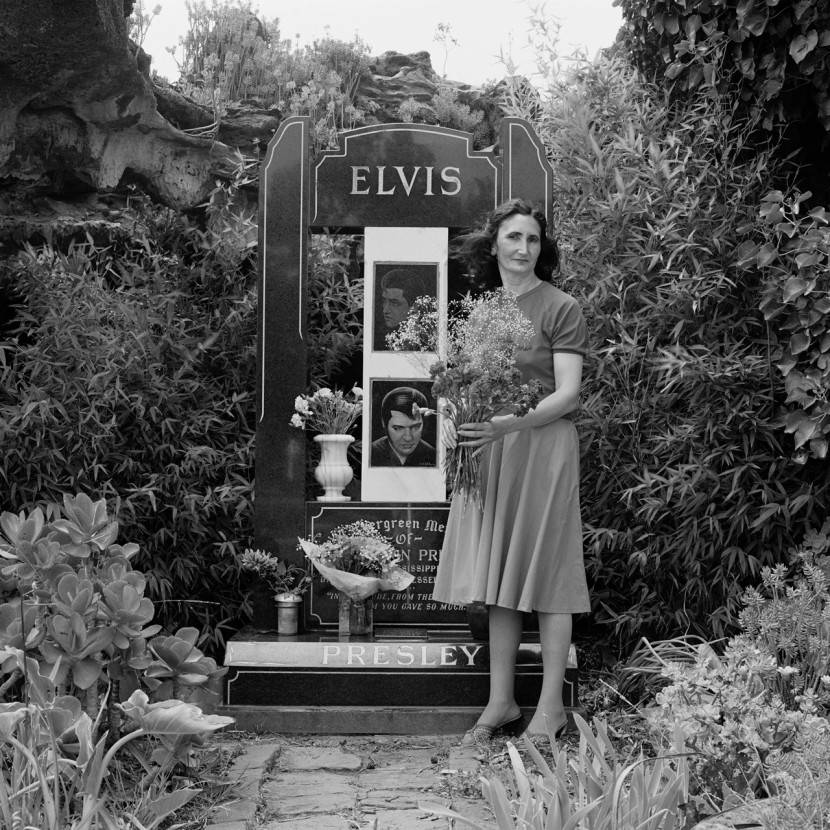

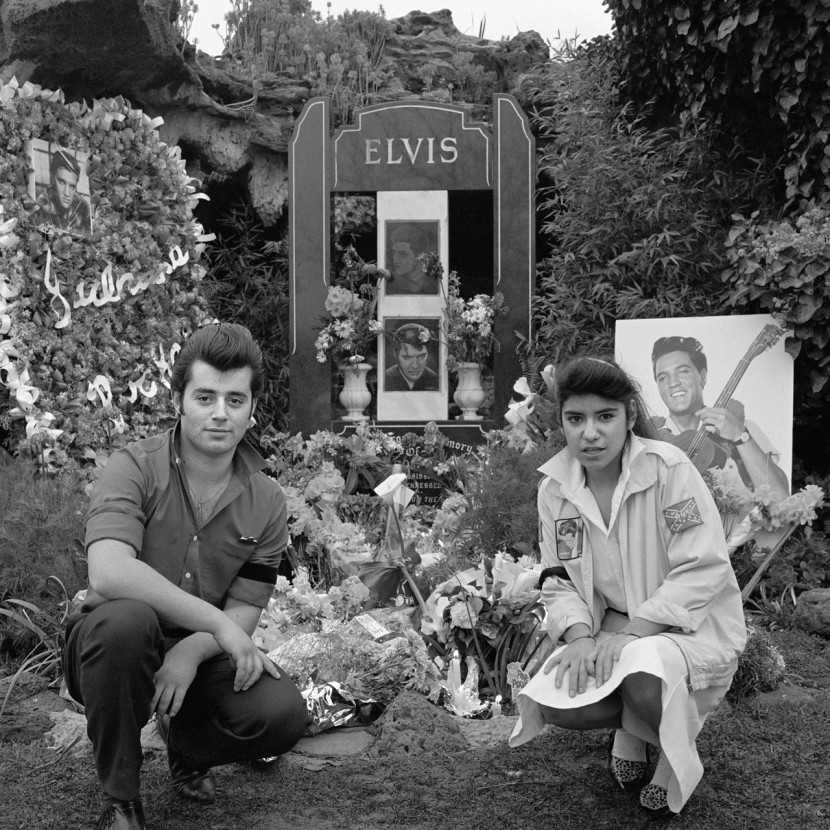

These photographs of the gatherings in Melbourne General Cemetery on the anniversary of Elvis’ death could be mistaken for images of a ritual pilgrimage. Each year on August 16, fans travel to the site to mark the occasion, many arriving in Elvis-themed clothing or period-specific fashion. The event functions as a memorial and a meeting point for Australian Elvis fans, combining commemoration with social ritual and performance.

Anchored by a memorial stone installed in 1977 and unveiled by Australian rock ’n’ roll pioneer Johnny O’Keefe, the site remains the only officially sanctioned Elvis Presley memorial outside of Memphis. Its existence reflects the seriousness of Elvis fandom in Australia: by the late 1980s, the country had approximately 16,000 registered Elvis fan club members, supported by a vast and organized network of local chapters and national organizations sustained long after Presley’s death.

Australia’s relationship with Elvis is, at first glance, paradoxical. Presley never toured the country, nor did he ever perform outside North America after the 1950s. Yet his image took root with unusual force in postwar Australia, a society newly attuned to American music, cinema, and style. Rock ’n’ roll arrived via radio waves, imported records, and films. Part outlaw, part romantic, part sacred object, Elvis quickly became its most visible representative, shaping local ideas of style, masculinity, and youth culture.

Without live performances to anchor fandom, Australian audiences developed their own systems of engagement. Fan clubs, memorial sites, anniversary gatherings, and later large-scale festivals provided structure and continuity. The Elvis Presley Fan Club of Australasia, founded in 1965 and officially recognized by Graceland, became one of the longest-running Elvis organizations in the world. Its activities included dances, talent competitions, exhibitions, and organized trips to Memphis and Las Vegas.

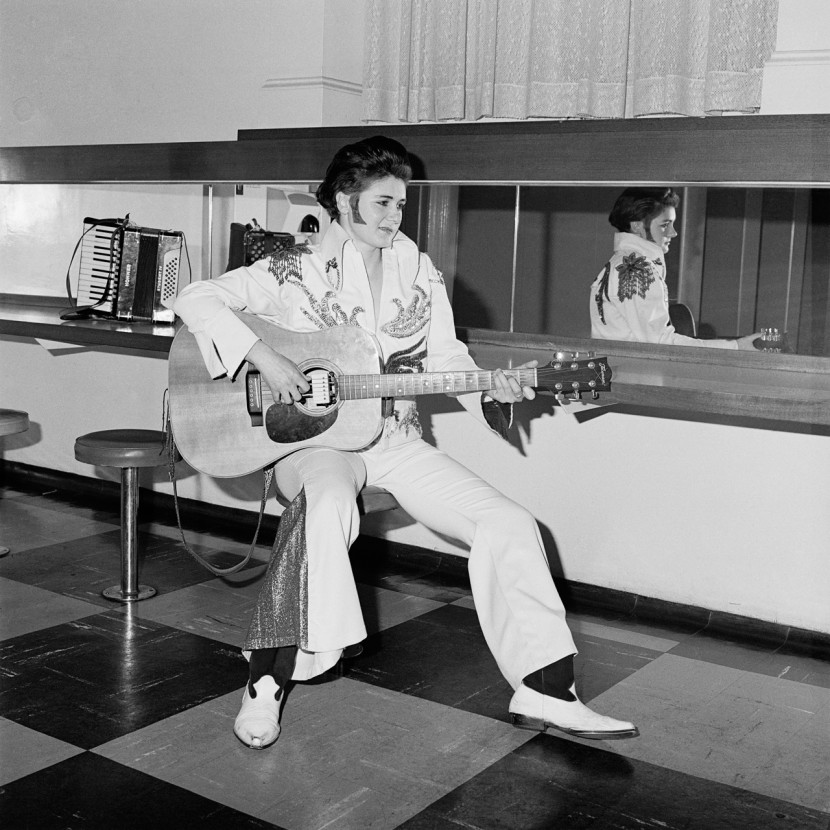

Polixeni Papapetrou’s Elvis Immortal (1987–2002) captured this devotion with an unusual balance of empathy and distance. Rather than treating Elvis fandom as novelty or spectacle, Papapetrou approached her subjects with a steady steady attentiveness. The photographs glow with the fervor of Presley’s earthly followers, a radiance that emerges because she shares their appreciation of Elvis’ sensual flamboyance while remaining a careful observer of the freedoms his image permits: the chance to step outside the ordinary, to perform masculinity or vulnerability, to temporarily inhabit a myth larger than oneself. Elvis becomes less a historical figure than a symbolic grammar, one that can be learned, embodied, and passed on.

Her subjects include impersonators, collectors, archivists, interpreters, and long-term fans. Many pose deliberately for the camera. Some wear meticulously researched jumpsuits modeled on specific concerts; others adopt looser, hybrid forms, blending everyday clothing with iconic signifiers like sideburns, pompadours, or heavy rings. What unites them is not mimicry alone but belief. Impersonation here functions as a serious cultural act: a disciplined, almost devotional practice through which Elvis is continually reanimated.

In this sense, Papapetrou’s photographs align with broader Australian Elvis culture, which includes suburban tribute nights and the Parkes Elvis Festival in New South Wales, which began in 1992 as a modest birthday celebration and has since grown into a five-day event attracting over 20,000 attendees annually. Costumed parades, gospel services, vow renewals, and even a dedicated “Elvis Express” train transform an inland town into a temporary capital of Presley’s afterlife.

Produced over a fifteen-year period using a square, black-and-white format, Elvis Immortal reflects Papapetrou’s long-term engagement with her subjects. Papapetrou returned annually to the Melbourne cemetery gatherings, gradually earning access to the private worlds of her subjects, creating an window into how the cult of Elvis evolved from the late 80s to the earliest years of the 2000s.

Beyond the public rituals, she documented domestic Gracelands assembled in suburban living rooms, carefully preserved vinyl collections, scrapbooks, and relics treated with near-religious care. She photographed intimate performances enacted for no audience beyond the camera itself. These interiors, mundane but reverential, reveal how fandom infiltrates daily life, becoming less an escape than a structuring presence.

The visual consistency of the series reinforces its documentary character. Papapetrou’s use of black and white, controlled lighting, and careful framing reduces visual distraction and places emphasis on gesture, costume, and expression. The square format produces a sense of visual containment, while the tonal range remains even and restrained.

The photographs avoid visual exaggeration, presenting their subjects with the same seriousness given to any long-term cultural community. The work asks the viewer to suspend irony and judgment, to recognize belief not as naïveté but as a human strategy for meaning-making.

Elvis Immortal stands as a tender study of fandom and popular cult-making. It documents not only the persistence of Elvis as a global icon, but the particular way his myth was translated, preserved, and embodied in Australia. These gatherings resemble secular rites: anniversaries observed with precision, ceremonial journeys undertaken annually, identities reaffirmed through costume and song. That Papapetrou encountered such intensity in Melbourne is no accident; it reflects a broader cultural history in which American music was absorbed, adapted, and locally maintained rather than simply copied.

The series also sits within Papapetrou’s wider body of work, which since the early 1980s has examined communities organized around shared identities and performative practices, including bodybuilders and Marilyn Monroe impersonators, communities bound together by shared myth, longing, and collective self-fashioning. In Elvis Immortal, this approach is applied with restraint and clarity. The work does not ask whether belief is justified, nor whether Elvis “deserves” such devotion. Instead, it documents what it looks like when popular culture briefly takes on the gravity of ritual, how it is practiced, and how it persists over time.