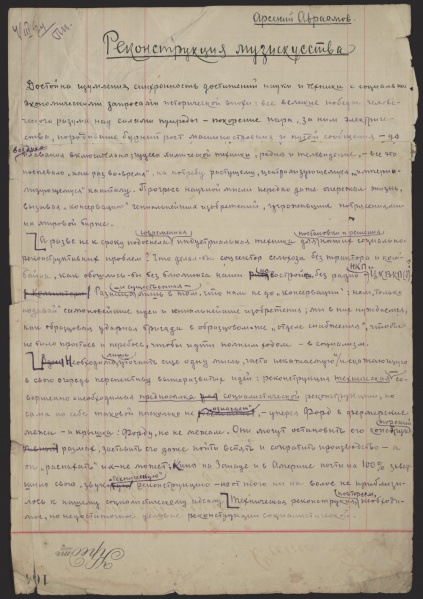

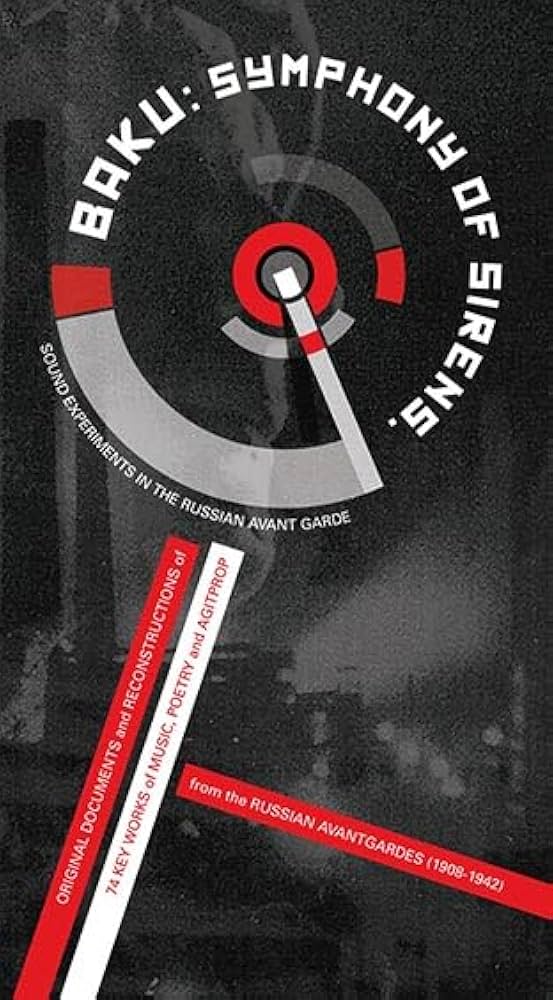

In September 1922, amid the fifth anniversary commemorations of the October Revolution in the capital of Azerbaijan, a little-known Russian music theorist realized one of the most audacious sonic projects of the early Soviet period: The Symphony of Sirens. His life is a story of radical invention, ideological fervor, and hearing the future of music long before anyone else could.

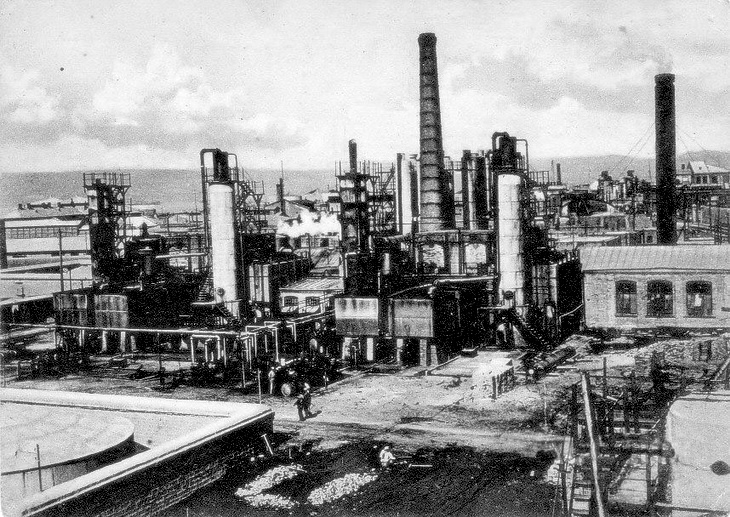

Staged in the oil port of Baku on September 23 (and tied to the broader November anniversary celebrations), the event proposed a radical premise. Rather than composing for an orchestra, Arseny Avraamov would orchestrate the city itself. Factories, oil fields, ships, military units, aircraft, and massed citizens were to function as ‘instruments’ in a single, coordinated composition.

Across Europe, avant-garde movements such as Futurism and Dada had already rejected inherited aesthetic forms and embraced rupture, machinery, and the violence of modernity. A decade prior, Italian composer Luigi Russolo had already called for the inclusion of industrial noise in music. Avraamov extended this logic further. His aim was both aesthetic and political: to dissolve the boundary between music, industry, and revolutionary spectacle. Industrialization was both performer and performance. The work aligned aesthetic radicalism with political symbolism, presenting mechanized sound as the audible expression of a new socialist order.

Avraamov’s initial concept envisioned a “symphony of the city” distributed across miles of urban space. Although the Baku performance was more contained than originally imagined and faced several issues, it remains unprecedented in scale to this day. All major factories and oil fields were instructed to sound their sirens in coordination. The Caspian flotilla contributed foghorns; locomotives added whistles; artillery and machine gun fire were incorporated as compositional elements; planes entered the sky; church bells, long associated with the old order, were folded into the composition; and a mass choir of thousands participated vocally, while onlookers were encouraged to join in the singing.

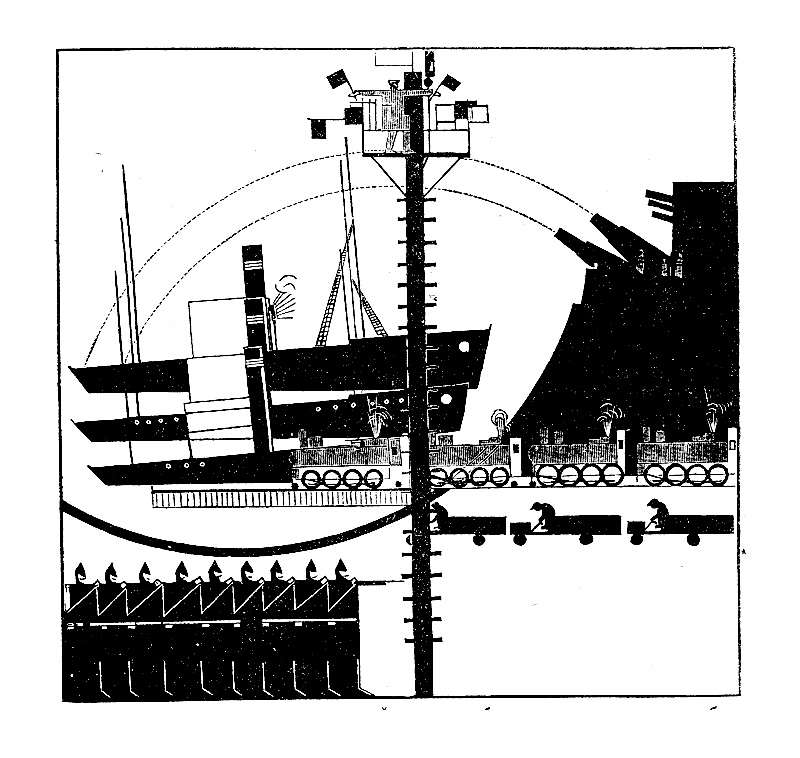

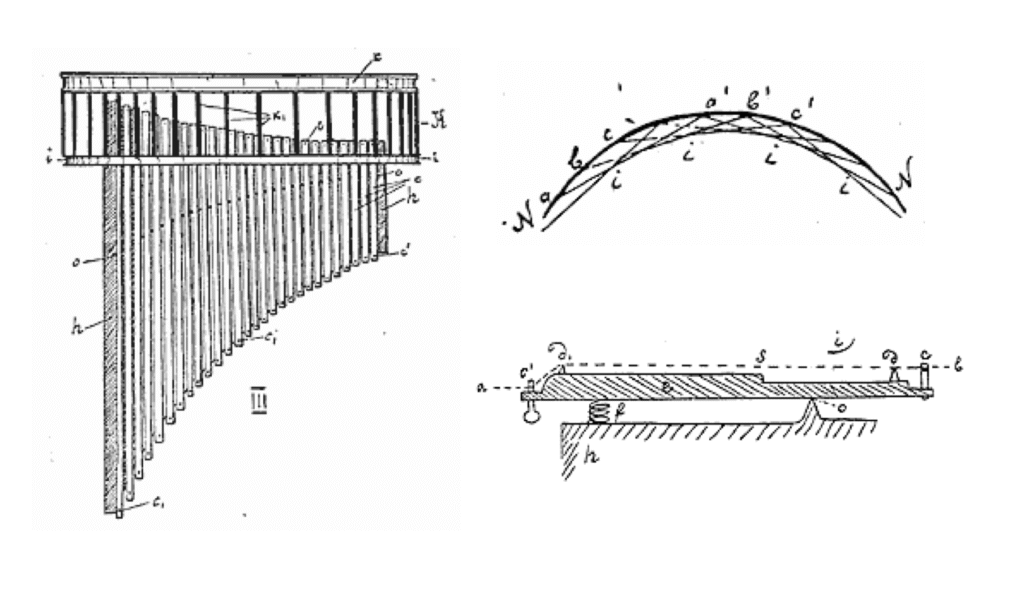

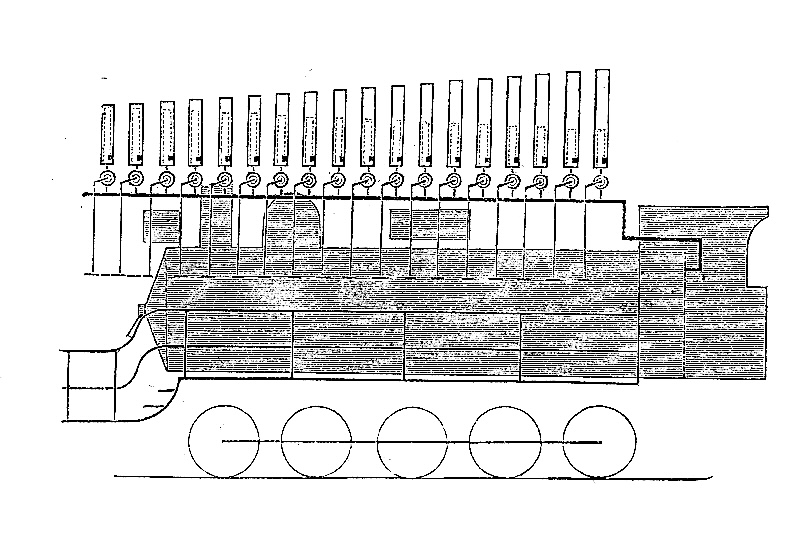

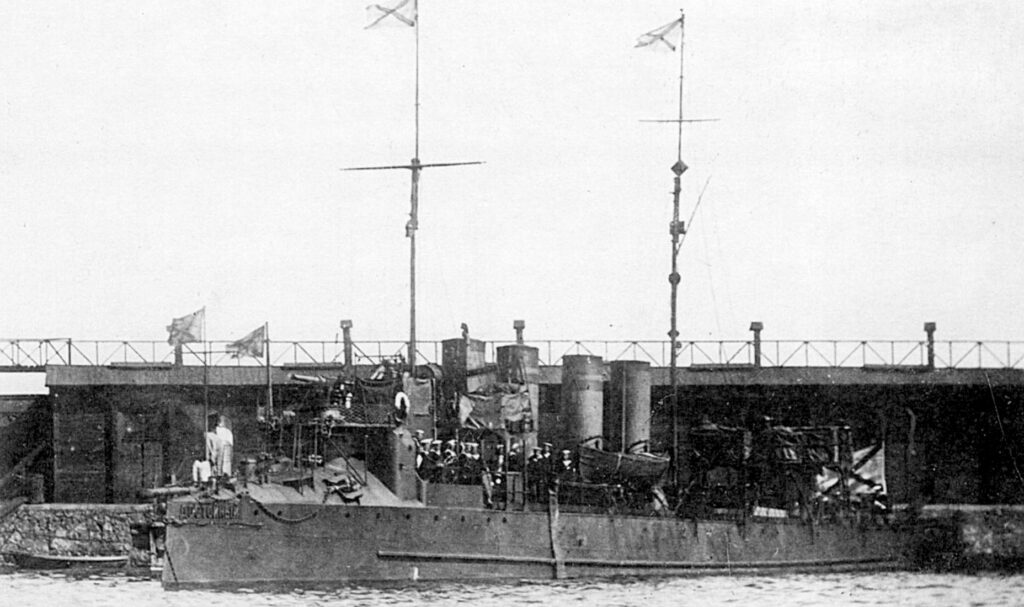

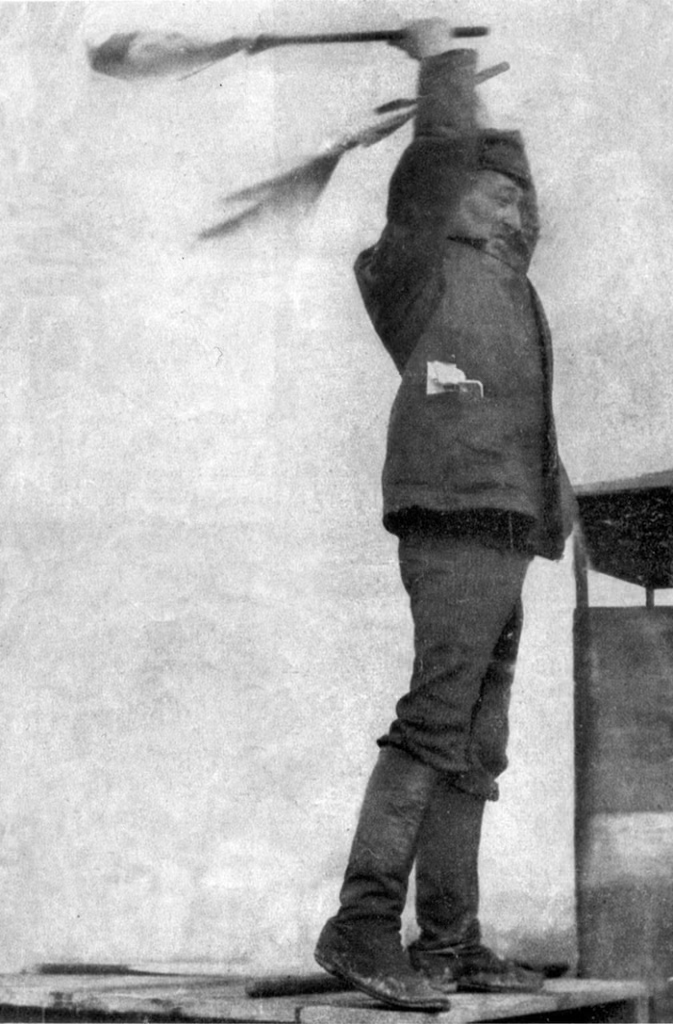

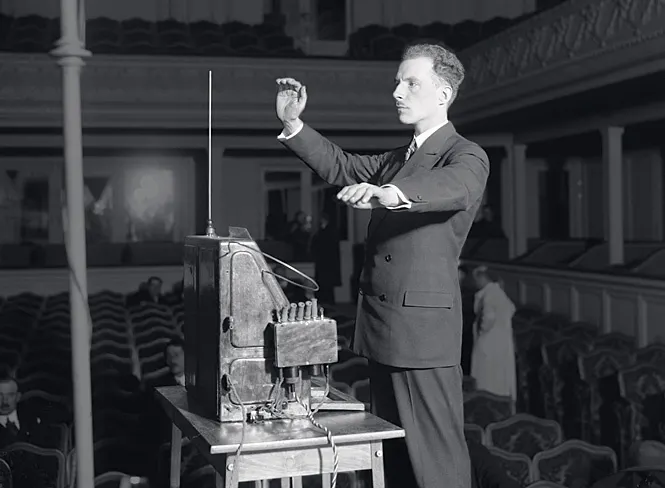

Central to the event was an instrument Avraamov designed specifically for the occasion: the Magistral. Constructed from fifty steam whistles mounted to pipes and operated by twenty-five musicians, it was built to be controlled in a manner analogous to a keyboard instrument. A separate unit of twenty-five performers aboard the torpedo boat Dostoiniy handled a separate set of whistles, expanding the tonal field across the harbor. Meanwhile, Avraamov served as a conductor, coordinating the entire performance from a tower overlooking the port, using colored signal flags and field telephones to coordinate the dispersed sound sources.

The wave of the first flag signalled a cannon to fire. The first shot signaled the factories’ sirens; subsequent shots activated dock and flotilla sirens in sequence. A military brass band began marching toward the harbor. Locomotive horns and machine-gun bursts entered the texture, accompanied by the whistles of the Magistral. At one point, seaplanes lifted off as thousands of voices shouted “Hurrah.”

The Internationale emerged gradually, beginning as a faint chorus before expanding into a massed choral statement. Later, the brass band introduced La Marseillaise, while cannons fired into the sea and machine guns into the sky. Church bells joined at the height of the crescendo, collapsing sacred and industrial sound into a single overwhelming field. The composition concluded abruptly after a final convergence of sirens, choir, brass, and the Magistral. Finally, a weighty silence hung over the city, its residents having just witnessed one of the most ambitious music performances in human history.

This moment was the literal and metaphorical height of Avraamov’s career. everything he had worked on prior and immediately following this moment was centered around this moment. Much of what followed would reference this moment, but none would match its scale or its clarity of intent. In Baku, Avraamov briefly achieved what he had theorized: the total transformation of music into a revolutionary instrument.

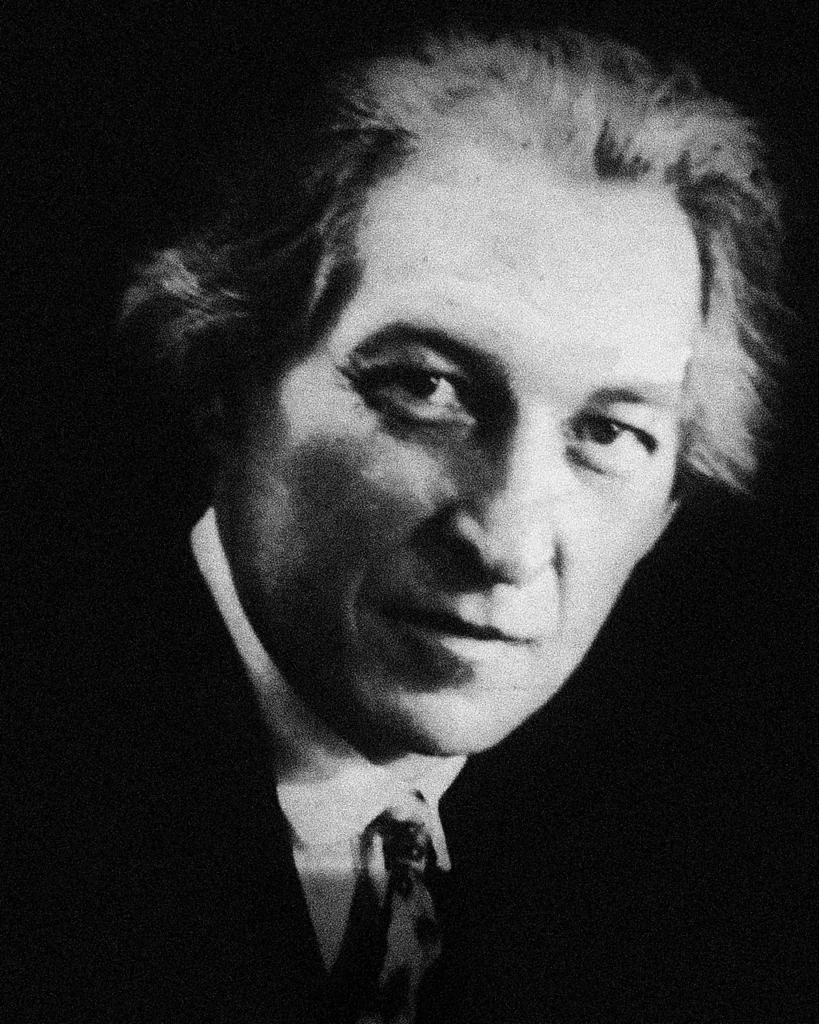

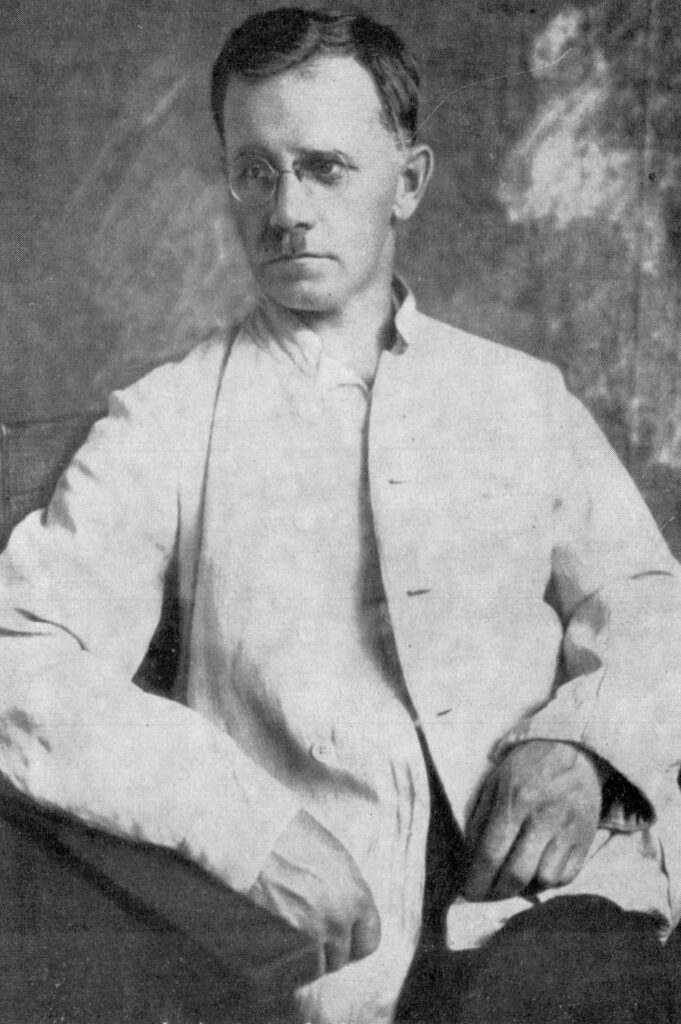

In life, Avraamov was known to people by many identities. Depending on the moment and the witness, he appeared as a cossack, militant revolutionary, inventor, acoustician, composer, vagrant, professional horse rider, folklorist, journalist, sailor, gymnast, oil worker, commissar, circus clown, and more. He was institutionally embedded in the young Soviet cultural apparatus: a founding participant in Proletkult, affiliated with a staggering amount of cultural and educational institutions throughout his lifetime. He organized research societies, established a sound laboratory, and became one of the earliest figures in the USSR to defend a doctoral dissertation in a musical-scientific field. He encountered figures at the center of Soviet power, including Lenin and leading Moscow poet Yesenin, yet spent equal time among remote mountain villagers in Central Asia.

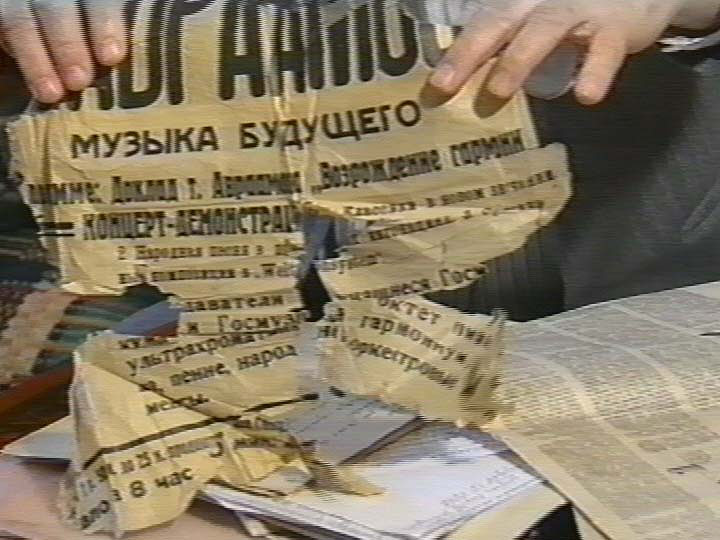

Even his name was unstable. Across different periods he appeared as Arseny Avraamov, Revarsavr, Dmitry Donskoy, Arslan Ibrahim-ogly Adamov, and Axel Smith, among others. His manifestos on the “music of the future” were signed with cryptic aliases: Ars (shortened form of Arseny, but also the latin word for “art”), Az, and occasionally Perditur (latin for “destroyer”). He seldom revealed his true name to anyone.

The contradictions extended into his worldview. He rejected religious authority and traditional sacred music, yet repeatedly invoked biblical language and imagery in his writings, embraced names with scriptural overtones, and was known to understand the Hebrew language, despite never referencing it in his extant work. Like his compositions, Avraamov’s intellectual life moved between revolution, ritual, science, and mysticism, a figure attempting to redesign sound while still speaking in the symbolic vocabulary of the past in the service of the materialist future.

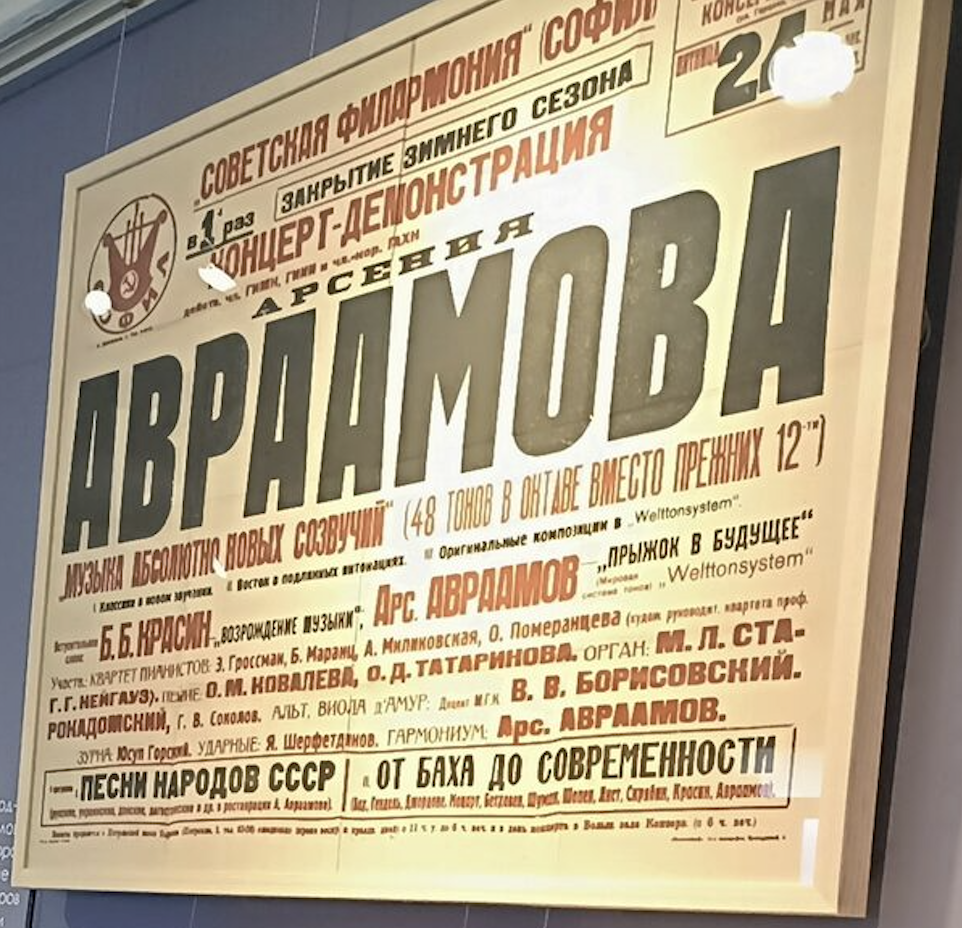

At the center of his thinking was a rejection of the Western well-tempered system. To Avraamov, the twelve-tone octave was not a neutral convention but a technological constraint that shaped how people heard the world. He eventually proposed a 48-tone “ultrachromatic” scale, the Welttonsystem, intended to reconcile tempered tuning with the natural overtone spectrum. Microtonality, for him, was not decorative complexity but a corrective: a way to align musical pitch with the physics of sound itself. This defined his life’s work, and his hostility to traditional tuning could border on the theatrical. In conversation with Commissar Anatoly Lunacharsky, he reportedly suggested burning every piano in Russia, arguing that the instrument embodied the ideological rigidity of tempered harmony.

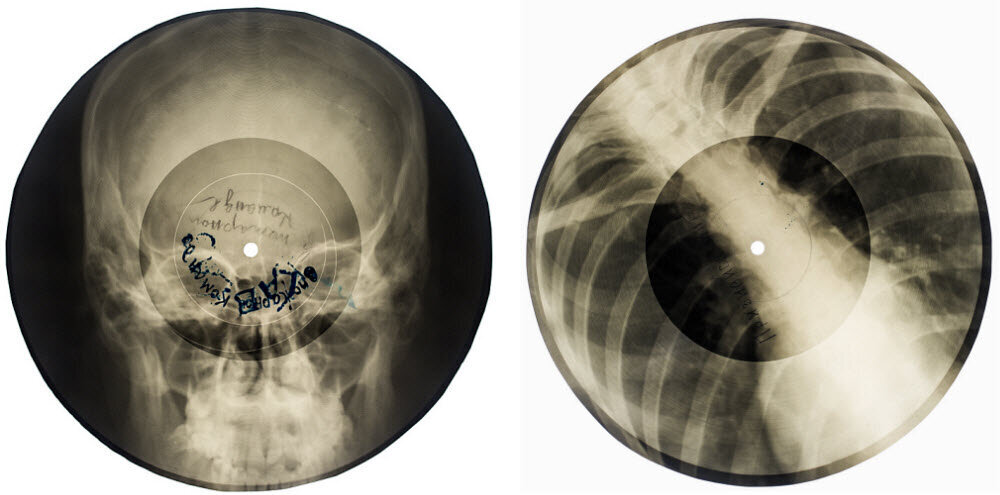

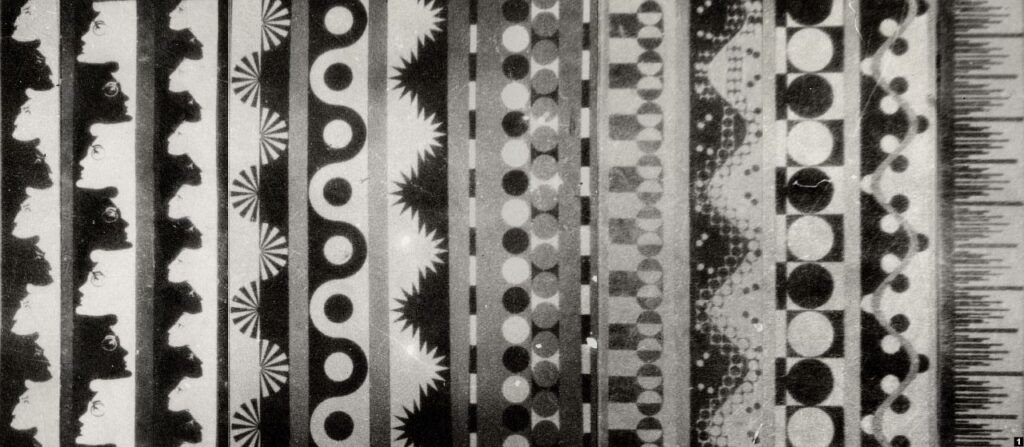

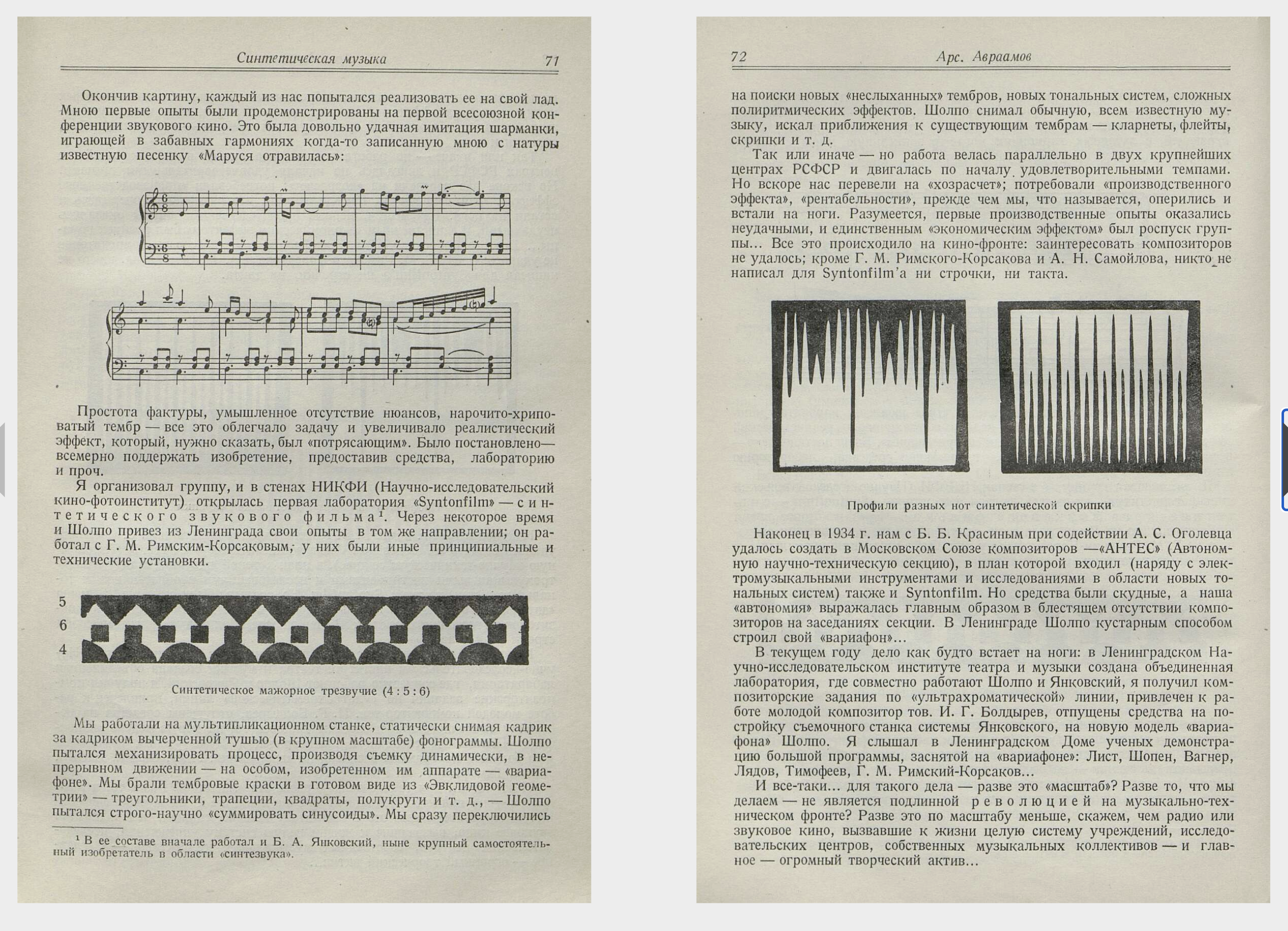

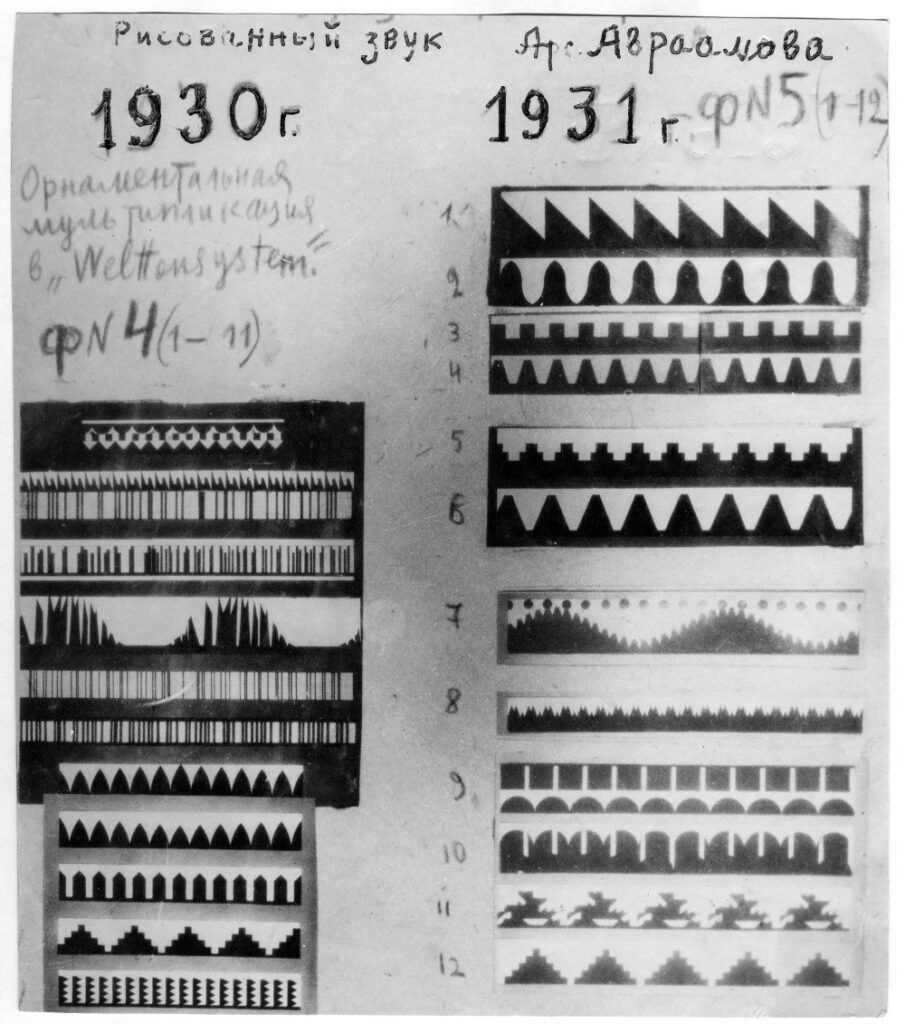

Over his lifetime, Avraamov was incredibly prolific and his experiments extended well beyond large-scale urban performance. As early as 1916 he explored primitive forms of sound synthesis and sampling. A decade later, became a pioneer of electronic sound, devising methods for transferring sound waves directly onto film stock while working on the soundtrack of the first Soviet sound film, generating audio from drawn shapes rather than recorded vibration, preceding the first commercially available computer music by decades. In other projects he attempted to sonify algebraic equations and even chemical orbital structures, treating scientific data as potential musical material.

Accounts of Avraamov’s life are complicated by his own tendency toward mythmaking. In addition to his many aliases, he cultivated an aura around himself and occasionally dramatized details, yet the broad outline of his biography is well documented across multiple sources.

He was born Arseny Mikhailovich Krasnokutsky on the Maly Nesvetay farm near Novocherkassk into a prosperous and well-educated Don Cossack family. His father, Mikhail Kharitonovich Krasnokutsky, was a major general while his mother taught literature. Naturally, Arseny’s brother Aleksandr became both an officer and a poet. His family’s reputation carried a distinction that carried prestige before the Revolution and potential danger afterward. Avraamov rarely used his birth name in adulthood, aware that association with a high-ranking imperial officer could prove fatal in the volatile political climate he was growing up in. According to his daughter, the surname “Avraamov” first arose simply to distinguish him from numerous Krasnokutskys in his native village, though its Old Testament resonance gave it symbolic weight, and it was often a name chosen by priests rather than people in secular fields. For a Cossack officer’s son to adopt such a name was unusual, but for an artist seeking distance from military lineage as well as a break with inherited roles, it made a certain sense. Though he seldom spoke about his parents, it was nonetheless his ancestry that secured entry into elite cadet education.

Despite some musical education beginning at the age of five, his upbringing pointed firmly toward a military career. As a teenager he began his studies in military sciences at the Don Cadet Corps in Novocherkassk. Still, he found an opportunity to explore other interests. At the Corps he combined formal studies with private musical pursuits, learning instruments and attempting early compositions. Yet the institutional environment suffocated him, and he turned his attention to another interest: politics. At fifteen he imagined shaking the foundations of the society he lived in any way he could.

As early as 1901, Avraamov organized a secret circle comprised of like-minded cadets who shared an interest in the Decembrists, an early attempt at staging a revolution in Russia, as well as and the ideals of the French Revolution. The group also revered other revolutionary figures from history such as the rebel Stenka Razin, a subject Avraamov attempted to write an early opera on based on a poem of another writer, Dmitry Navrotsky. Members of the group were especially fans of the work of French writer Félix Gras, who published a historical novel of the French Revolution just five years before.

Despite his father’s rank, he never intended to serve as an officer and aimed for something beyond the bounds of society. “When we parted at the end of our course (in 1903), we made traditional vows to each other: to give our lives for freedom and the people, to revive the former glory of the Cossacks.” Avraamov recalled. Following his education in Novocherkassk, his parents forced him to continue his education in St. Petersburg at the Mikhailovsky Artillery School, which he protested. “There, I pursued a tactic of sabotaging my studies… I excelled in higher mathematics, chemistry, and artillery—but in all other subjects, I stubbornly received “1s” and even “0s”… Of course, at that time, I diligently contributed to liberal youth magazines and played music, always waiting for the opportunity to “do” something so drastic that I would be “kicked out” of the School myself.” Less than a year into his education in St. Petersburg, he intensified his campaign of academic sabotage and political dissent. After delivering a speech condemning both the military education system and the broader government order, he was branded a dangerous revolutionary, placed under police supervision, and effectively ended his military career before it even began. This, along with his purposely failing grades, gave him the result he had hoped for. He was expelled and sent back home to his parents.

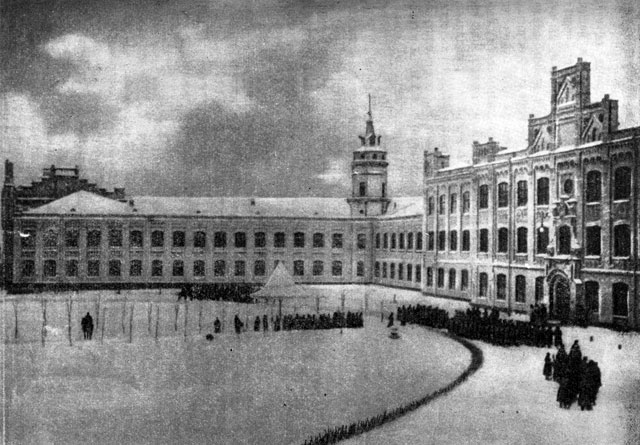

He was undeterred, by autumn 1904 he was traveling between Russian towns participating in social-democratic political organizing on behalf of various student groups. Soon he moved to Ukraine and enrolled at the Kiev Polytechnic Institute, a place that carried a reputation for being a hotbed of political dissidence following a 1899 strike that resulted in the expulsion, arrest, and exile of 32 students as well as the formation of an underground revolutionary committee connected to the city’s wider movements. Just six months into his education there, attempts at revolution once again took hold, this time all across the Russian Empire.

On January 15, 1905, Avraamov joined his fellow students in seizing the institute building using fire hoses and improvised chemical bombs. Following the events of Bloody Sunday just a week later, the students dug in, establishing a commune some 150 to 200 students strong, lending their support to socialist revolutionary and social democratic parties that were currently participating in wider unrest across the empire. The commune served as a major center of revolutionary activity in Kiev before it was subdued by a combined effort of police and military. Following the October Manifesto issued by Emperor Nicholas II in an attempt to restore order, the revolutionary activity died down for the moment and Avraamov returned to Novocherkassk. Determined to continue the momentum, he delivered a pro-communist speech almost immediately upon arrival and immediately faced the threat of reprisal. He fled once again to Rostov, only to find volence engulfed the region there as well, a close friend had been killed in a pogrom, and he once again left before he could be targeted.

The months that followed were marked by constant movement and deepening underground involvement. On the road back toward Kiev he received a Mauser rifle from a sympathetic militant, an Armenian terrorist, which he kept for years as his political activities intensified and he came under further scrutiny. Upon returning to the city, he found relative safety in the form of falsified documents under the name Dmitry Ivanovich Donskoy along with a “wife” to lend credence to the identity, arranged by his allies in the Ukrainian revolutionary movement. The arrangement proved short-lived. On November 18th, 1905, he was once again involved in an armed insurrection. In the process, authorities searched his apartment and discovered bomb-making materials hidden in a laundry basket, forcing him to flee. He spent months evading arrest before returning to Rostov in spring 1906, still only twenty, to find familiar political organizations he could have once counted on dismantled and repression ongoing.

At this point he attempted a decisive rupture with his past. Abandoning the Donskoy identity and withdrawing from direct revolutionary activity, he turned toward an unexpected field: music. Determined to escape the military environment entirely, he left for Moscow in 1906 and, against his parents’ wishes, enrolled in the Music and Drama School of the Philharmonic Society, studying theory and composition.

Up to this moment, music had appeared only intermittently, as a childhood lesson, a cadet’s pastime, or a parallel interest alongside politics and agitation. The abruptness of the shift is striking. As he later wrote, with notable understatement: “I decided to pursue musical studies and the following year enrolled in the Moscow Philharmonic School, majoring in composition, where I studied until 1912.” The decision marked more than a career change. It redirected a revolutionary temperament toward the structures of sound itself, a move that would eventually lead him to challenge not only musical tradition but the acoustic foundations of modern life.

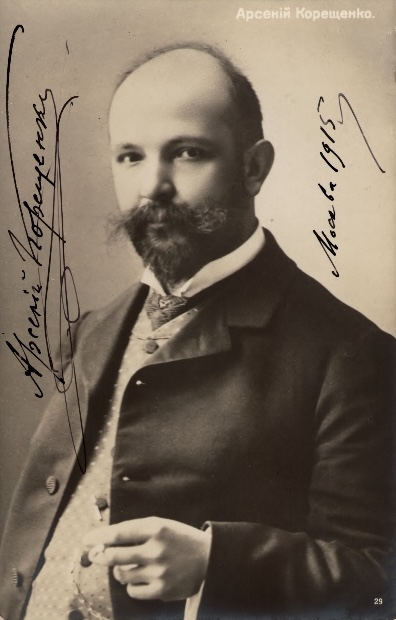

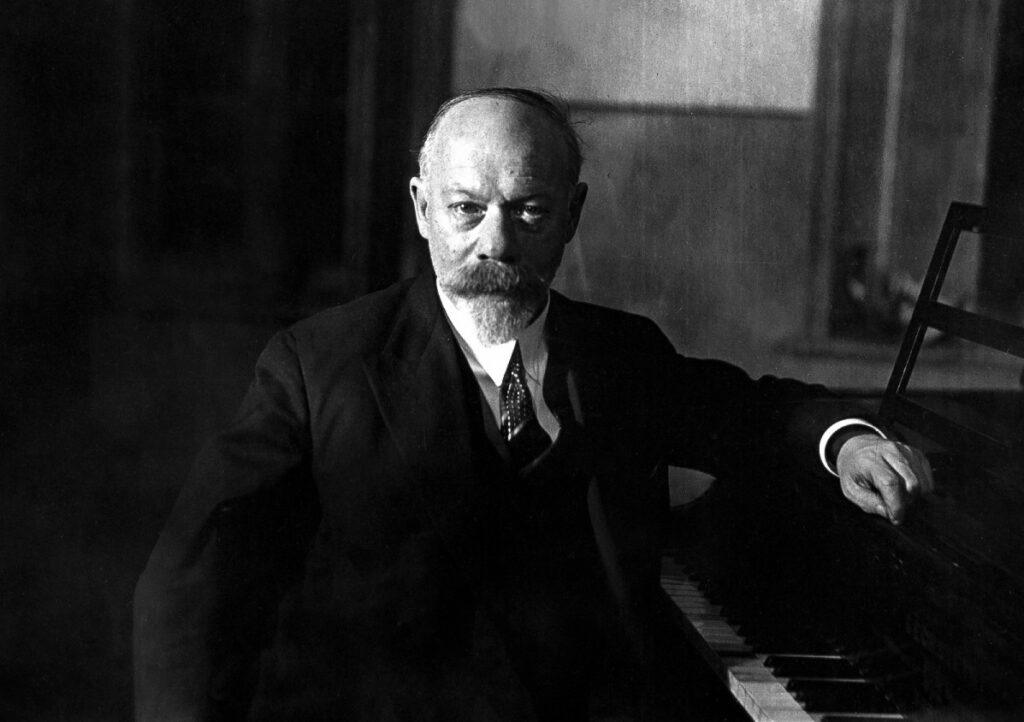

Compared with the turbulence of his early revolutionary years, the period between roughly 1908 and 1912 brought a measure of stability. During these years Avraamov immersed himself in formal musical study in Moscow. From 1908 to 1911 he studied music theory in the classes of the Moscow Philharmonic Society under Ilya Protopopov and Arseny Koreshchenko, while also taking private composition lessons with the composer Sergei Taneyev. By 1910 he had begun publishing as a music critic under the pseudonym Ars, contributing essays and commentary to student newsletters as well as Moscow and St. Petersburg periodicals, including the weekly Music, the journals Musical Contemporary and Letopis (Chronicle), as well as the German magazine Melos. In choosing music over a military career, he became the first member of his large Cossack family to pursue an artistic profession.

Determined to sever ties with the militarized environment in which he had been raised, he pursued rigorous musical literacy training. Protopopov, a composer and teacher of theoretical disciplines who wrote primarily for Orthodox liturgical services, provided a foundation in theory and church music traditions. Koreshchenko, a Moscow Conservatory graduate and former student of the Conservatory’s Professor of Piano Pavel Pabst, taught harmony and solfeggio and was known for operas such as Belshazzar’s Feast and The Angel of Death, the ballet The Magic Mirror, incidental music for Euripides’ tragedies, symphonic works, a lyric symphony, the cantata Don Juan, and arrangements of Armenian and Georgian songs. Koreshchenko had also been active as a critic since his student years, writing on musical culture and particularly on the songs of the Don Cossacks, a connection that likely resonated with Avraamov’s own background.

During this period Avraamov composed early chamber works that adhered to classical and traditional styles. Among them were Romance for Violin and Piano, a lyrical piece for violin with piano accompaniment, and Russian Dance, a composition evoking folk rhythms through conventional orchestration. These works, likely directly made under training under Taneyev and Protopopov, show his initial engagement with Western classical techniques before his later break toward radical experimentation. His formal musical education lasted only about six years, yet in that time he acquired proficiency in violin and piano performance, theory, and composition, a remarkably rapid accomplishment.

After completing his studies in 1912, Avraamov briefly studied composition and orchestration with Rimsky-Korsakov and returned to the Don region. There he worked as a music critic and lecturer, organizing what he called “symphonic chapels” in public reading rooms and leading musical-ethnographic expeditions to Don Cossack villages. These expeditions documented folk traditions but also functioned as vehicles for political agitation and propaganda, as he later acknowledged. His activities drew attention from authorities; he was reportedly press-ganged, captured, and thrown into military service.

Before long, his past caught up with him. While serving in a Cossack military division, his early life as a revolutionary resurfaced and he was arrested and jailed for propaganda activities. Remarkably, he managed to escape imprisonment, fled north, and eventually reached Sweden and later Norway, now under the name Axel Smith.

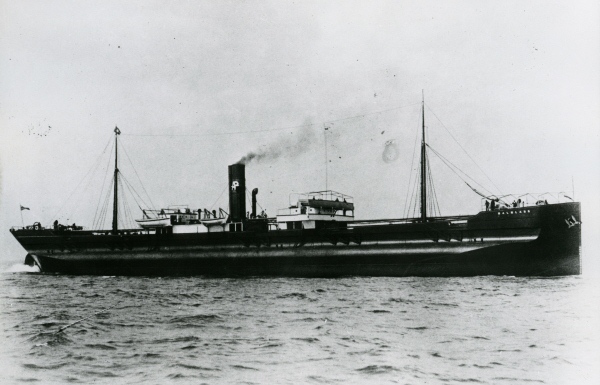

What followed was one of the most improbable episodes of his life. In 1913 he joined a traveling circus troupe. Presented as a Jigit, or a traditional Caucasian equestrian rider, he performed gymnastic routines on horizontal bars, demonstrated feats of Cossack trick riding, and worked as a musical clown. Following a short stint as a composer writing for local plays and performances, he was later hired on as a sailor in Norway, working as a stoker on steamships. After less than a year, now aboard the Swedish cargo ship Malmland, he traveled through Holland and Germany and finally made his way back toward Russia.

Arriving back in the Russian Empire by boat, Avraamov attempted to cross the border and was promptly arrested. He was released under an imperial amnesty issued to mark the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty, arrested again soon afterward, and ultimately declared mentally unfit, a bureaucratic maneuver that ended the immediate cycle of detention. At this point music returned decisively to the foreground. He left for Moscow and St. Petersburg, resumed musical research and invention, and reentered the press as a critic and theorist.

These years, oscillating between conservatory training, ethnographic fieldwork, political persecution, and itinerant life under assumed names, reveal a figure in constant motion. Even in this ostensibly “peaceful” phase, Avraamov’s life unfolded as a sequence of abrupt transformations, each widening his understanding of sound, performance, and the social role of music.

Settling first in St. Petersburg between 1914 and 1916 he gradually rejoined the intellectual and musical circles he had abandoned years earlier. He became a member of the editorial boards of Muzykalny Sovremennik (Musical Contemporary) and Letopis (Chronicle), while in Moscow he worked for Muzyka magazine. In a series of articles published during these years he elaborated his theory of microtonal ultrachromatic music and proposed new instruments capable of performing it.

Ultrachromatism refers to an expansion of the conventional twelve-tone equal-tempered system into finer divisions of pitch, aligning it closely with microtonality. Emerging in the early twentieth century through figures such as Ivan Wyschnegradsky, it rejected the limits of standard chromaticism by employing micro-intervals — quarter-tones and smaller — to open new harmonic and melodic terrain.

This idea was most popular with the Futurists, a movement that sought to break decisively with the cultural weight of the past and align art with the speed, machinery, and violence of modern life. Emerging in Italy before the First World War, and taking an especially strong hold in Russia, Futurism rejected tradition, celebrated industry and urban energy, and demanded forms of expression capable of matching a mechanized age.

Russolo, a major influence for many Futurists in Russia, called for music to absorb the sonic reality of the industrial age, treating mechanical and urban sound as legitimate musical material. Yet for many Futurists and post-Futurist experimenters such as Avraamov, this was only a beginning: the goal was not merely to incorporate new sounds, but to redesign the very foundations of musical structure and listening itself.

Despite his erratic biography, Avraamov had already established a reputation as a formidable critic and theorist. Composer Nikolai Roslavets wrote a letter of introduction to fellow musician and Futurist theorist Nikolai Kulbin urging him to assist “the skilled musician and the most talented journalist writing mainly concerning art.”

At the center of Avraamov’s work was now a sweeping ambition: to reform the very structure of music. Armed with formal training, he redirected his revolutionary zeal toward sound itself. He denounced the twelve-tone, octave-based equal temperament system, which he believed had distorted human hearing for centuries, and argued that the piano, as its most visible embodiment, symbolized a crippling constraint on musical perception. In his articles, he explicitly rejected the well-tempered scale that had dominated Western music since the era of Johann Sebastian Bach.

He began formulating ultrachromaticism in the mid-1910s, arguing that traditional Western harmony imposed artificial limits on sound. In 1915 his essay Ultrachromaticism or Omnitonality, published in Muzykalny Sovremennik, he proposed a system that would transcend diatonic and chromatic structures through microintervals. As with many Futurists experimenting with sound, this was inspired by Alexander Scriabin’s expanded harmonic language. Avraamov rejected fixed temperaments as obstacles to natural acoustic evolution.

In 1916, in The Coming Science of Music and the New Era in the History of Music, he outlined a mathematical model of musical processes, predicted techniques akin to modern sound synthesis, and emphasized spectral analysis over discrete pitch systems. It begins with a resounding protest against limitation: “Science gave me the legal right to create timbres nearly a century ago, having broken down every sonic color into its component parts, pinpointing to me precisely all the elements from which I can synthetically recreate any timbre I desire! Why should I limit myself to crude, imperfect approximations, content myself with the “achievements” of some unknown, perhaps semi-literate, masters who inspire not a shred of respect? For what? … Listen carefully to the intonations of human speech, compare its limitless capacity for the evolution of timbre with the most perfect instruments we have in music — the cello and the violin: how poor their capabilities are, how murderously monotonous is all the “chamber music” of a century and a half up to and including today! … “What if it were already possible today to transform a sustained flute chord into a powerful brass tutti within ten seconds (completely imperceptible to the auditory sense), and then, three seconds later, transform it just as imperceptibly into the calm and clear timbre of a clarinetto?”

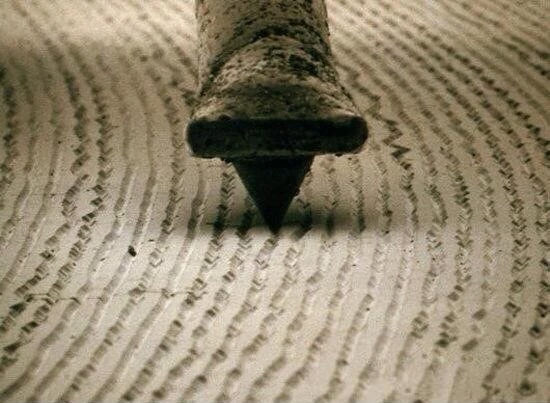

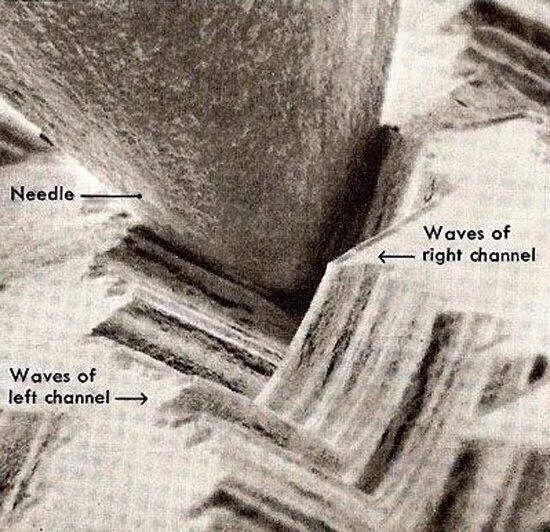

To accomplish this, he argued that by studying the physical structure of sound grooves on a phonograph record and reconstructing them synthetically, “one can create synthetically any, even the most fantastic sound by making a groove with a proper shape, structure and depth”. He proposed analyzing sound curves, directing a resonating needle, and constructing grooves of precise shape and depth to generate entirely new sounds, a concept anticipating sampling, resynthesis, and modern physical-modeling synthesis. The seed that would later grow to become the synthesizer and later digital music production as we know it today.

He wrote that science had already provided the means to decompose timbre into component elements and recombine them synthetically, making it possible to transform one instrumental color into another imperceptibly over time. He imagined devices employing tuning forks, electromagnetic currents, and controlled overtone activation to morph a flute chord into brass sonority and then into clarinet tone. He compared the expressive richness of human speech with the relative monotony of orchestral instruments and argued that composers should be able to sculpt timbre as fluidly as melody.

Avraamov insisted that musical knowledge, scales, rhythm, harmony, counterpoint, and instrumentation, could be placed on a rigorous scientific foundation. Mathematics, he argued, was essential not only to pitch relations but to timbre itself, requiring analysis of overtone series and the physical motion of strings, reeds, and air columns. He envisioned a future “science of music” that would systematize these principles into a coherent doctrine of creative possibilities.

As with his contemporaries in Rossolo, Wyschnegradsky, and others, Avraamov argued that discussing ultrachromatic possibilities was meaningless without new instruments capable of realizing them. Existing instruments, he believed, were fundamentally unsuitable. The new instrument, he argued, needed to meet three requirements. Firstly, a sustained tone with real-time dynamic control. Secondly, a completely free intonation across a continuous pitch spectrum, and lastly, polyphonic capability enabling a single performer to produce complex harmonic structures.

As an initial solution he devised the bowed polychord, an instrument capable of producing an “unlimited variety of harmonic complexes” within a continuous scale. A mechanical instrument whose bow wheel was operated by foot, the bowed polychord an impractical but symbolic step towards a new musical practice. Given his recent work as a circus musician and clown, the mechanical ingenuity of the device may owe something to performance spectacle as much as acoustical theory. Its absence of fixed pitches was intended to retrain hearing distorted by what he called the “Bach legacy,” render earlier repertoire unreproducible, and stimulate new harmonic forms. By now he was proposing division of the octave into 48 equal microintervals.

“J.S. Bach, one of the greatest true Futurists of his century, exemplifies the sad fate of Futurism in general: despite the unattainable (even for us) dimensions of his genius, his work can be accepted today only with significant formal reservations… Hence the furious vandalism (and unceremonious, at that) to which the great artist falls victim before our very eyes. It is impossible to justify the vandals, but it is not difficult to understand them: no matter how much the artist considers himself superior to modernity, he is still its flesh and blood, and future generations, if they appreciate his genius, will at least outgrow it both emotionally and technically: the bland aftertaste of the “historical” will be an eternal temptation for them to rectify their faded palates with the hot peppers of modernism.” he wrote.

Having described Bach as both a Futurist of his era and a criminal for delaying the logical evolution of sound, his positioned the musical past in revolutionary terms: both foundation and obstacle, but his theories were not just noise that fell upon deaf ears. In the same year as his essay was published, he was already teaching Musical Acoustics at the Presman Conservatory in Rostov-on-Don. During this period he continued writing about artificial timbre creation, effectively anticipating synthesizers decades before their widespread appearance. Although he had found early institutional success, his conflicts with the law did not cease. Later that same year, he had again faced trouble, this time in St. Petersburg, reportedly after being mistaken for someone else, though he ultimately proved his identity and remained out of prison or compulsory military service. As the First World War swept across Europe, Avraamov largely avoided the conflict. His brother Aleksandr, having still remained an officer in the military, met a harsher fate, dying on the frontlines of the war just a year before Russia’s involvement ended.

The pivotal year of 1917 in Russian history reshaped not only the country’s political order but the intellectual and artistic trajectory of the young composer and theorist Arseny Avraamov. In the months surrounding the revolution, he moved decisively from speculative inquiry into music theory toward institutional, technological, and ideological action. His writings from this period called for a union between artistic practice and scientific analysis, arguing that music could no longer remain a mystical or purely intuitive art. Instead, he urged collaboration among composers, engineers, mathematicians, and physicists to uncover the objective laws underlying sound and musical perception.

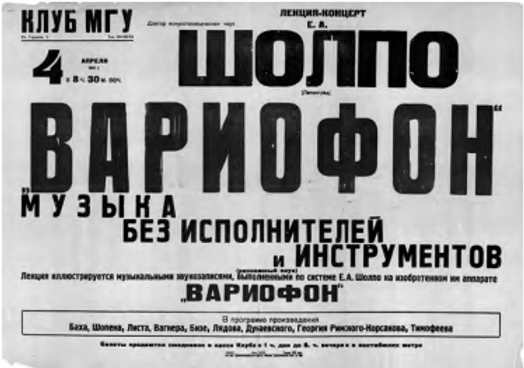

This vision began to take institutional form in the spring of 1917, when Avraamov, inventor Evgeny Sholpo, and the young mathematician and musicologist Sergei Dianin founded the Leonardo da Vinci Society in St. Petersburg. The group took inspiration from Leonardo’s synthesis of art and science, embracing empirical investigation and technological experimentation as tools for understanding the mechanics of artistic creation. Their goal was nothing less than a paradigm shift in music theory and technique grounded in interdisciplinary research.

Central to the Society’s research was the idea of “non-performing music”, sound produced through technological means rather than traditional instrumental performance. This concept, building on Avraamov’s essay from the year before, imagined what members described as an “alchemical” transformation of music: the generation of sound liberated from traditional notation, the physical limitations of performers and instruments, and anticipating a mechanized and scientifically controlled sonic future. From these investigations emerged the early foundations of what would become drawn sound, a technique in which sound waves could be directly inscribed onto film and converted into audio during playback. The conceptual roots of this idea can be traced to the futurist speculations of Velimir Khlebnikov, whose visionary writings imagined new technological languages and sensory systems. This would be an idea Avraamov would return to and continue to develop in later experiments with synthetic and graphic sound.

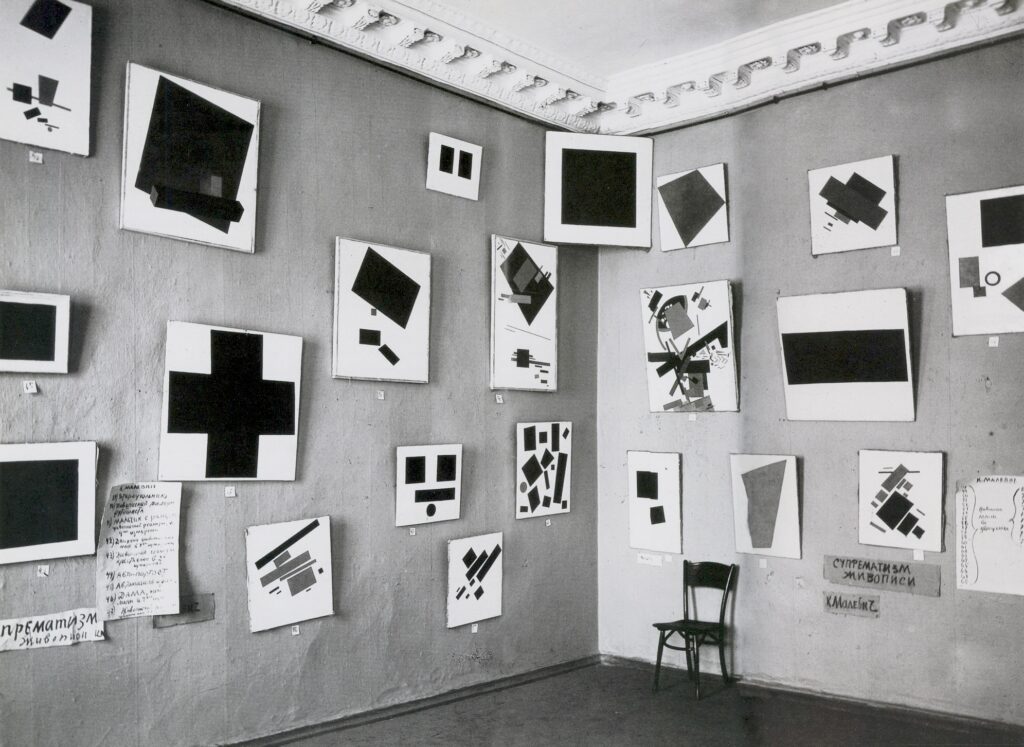

The October Revolution accelerated Avraamov’s ambitions for change. Sweeping reforms destabilized social hierarchies and cultural institutions, producing an atmosphere in which radical artistic ideas could be pursued with unprecedented urgency. In literature, this spirit manifested in the explosive futurist verse of Vladimir Mayakovsky; in visual art, in Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square and the Suprematist rejection of representation; In film this was best reflected in the provocative cinematography of Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein. For what concerned Avraamov, the change in music came in the form of proposals to abolish bourgeois concert traditions altogether and bring music out of the elitist music halls and into the streets.

Avraamov embraced the revolution not as an observer but as a participant. He was present at Smolny during the revolutionary period and soon collaborated with Anatoly Lunacharsky, the newly appointed People’s Commissar of Education. Adopting the pseudonym “Rev-Ars-Avr” (“Revolutionary Arseny Avraamov”), he became deeply involved in building a new Soviet musical culture aligned with proletarian ideals. Lunacharsky, a translator, publicist, art historian, critic, and writer, saw the potential in Avraamov and allowed him a degree of influence in the cultural affairs of the new Soviet state.

From 1917 to 1918, Avraamov assumed key positions within emerging Soviet cultural institutions. He served as Governmental Commissar of Arts within Narkompros (the People’s Commissariat for Education) and headed the Musical Department of Proletkult (Proletarian Culture) in Petrograd, an organization dedicated to cultivating a distinctly proletarian culture independent of bourgeois traditions. In these roles, he advocated for mass participation, industrial sound sources, and new collective forms of musical expression intended for workers rather than elite audiences.

In 1918, under Lunacharsky’s direction, Avraamov also worked within the music sector of Narkompros, including serving as Head of the Arts Department of Narobraz (The Committee for Education) in Kazan, where he oversaw musical culture in Tatarstan. His responsibilities included reorganizing cultural institutions, promoting new educational models, and encouraging musical forms that reflected revolutionary ideology and regional diversity, all while teaching ethnology at the conservatory and serving as professor of theoretical disciplines, although this role proved short-lived, reportedly ending after a falling-out with Anatoly Lunacharsky as the Civil War soon overtook institutional concerns. Avraamov continued his work within the army’s political departments while directing regional arts divisions in several cities considered strategically and culturally important: Nizhny Novgorod, Kazan, Saratov, and Rostov. In the latter city, he found time to serve as a professor at the Conservatory.

That same year, he began serving as a cultural curator within the Political Department of the Red Army, where he organized educational and agitational initiatives intended to strengthen Bolshevik morale among soldiers and cultivate ideological unity. These efforts aligned closely with broader Bolshevik strategies of mass agitation: culture was to function not as elite ornament but as a tool for forging class consciousness.

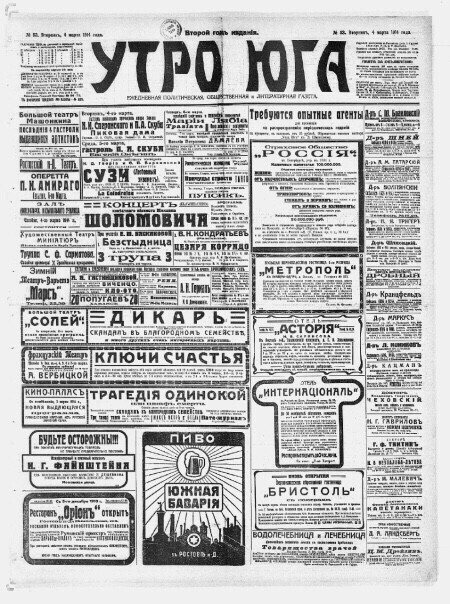

Concurrently, he edited the agitprop army newspaper On Guard of the Revolution, positioning print media alongside music education as instruments of ideological dissemination. His writings and criticism also appeared in regional newspapers including Donskaya Zhizn, Utro Yuga, Donskiye Oblastnye Vedomosti, and Rostovskaya Rech, extending his influence into the civic press.

For Avraamov, however, political revolution was only the beginning. He continued to envision a transformation just as profound in the realm of sound: the dismantling of inherited tonal systems, the mechanization of sound production, and the creation of a scientific, technologically mediated music suited to an industrial society. The revolutionary upheaval of 1917 provided both the ideological justification and the institutional framework through which he could begin constructing that future.

At the center of Avraamov’s reform program was the creation of a universal musical system grounded in microtonality, particularly a quarter-tone technique. He regarded the twelve-tone equal temperament system not merely as inadequate but as actively harmful, claiming it had dulled auditory perception and constrained musical thought. “Freed from the mold of temperament” he wrote, “human hearing will achieve such advances in the subtlety of melodic perception that we can barely dream of today. Folk song, whose intervals our ‘cultured’ hearing still cannot accurately discern, serves as a guarantee of the non-utopian nature of our dreams. Is our ear really more coarsely constructed? Is the systematic distortion of hearing by Bach’s legacy the cause? One way or another, the near future will tell… for we live ‘on the eve.’ ” Folk songs, according to Avraamov’s experience, were an art whose intervals trained musicians often failed to perceive accurately, proving to him that such refinement was not utopian but immensely useful towards the development of a truly universal theory of music.

Avraamov sought to replace the fixed chromatic scale with what he described as a continuous scale. Instead of twelve evenly spaced pitches within an octave, modern acoustics revealed an unbroken sonic continuum governed by mathematical relationships. Using this framework, he calculated systems of quarter-tones, eighth-tones, and finer subdivisions, arguing that any point within the continuum could be coordinated into harmony. He compared the shift to a primitive counting system suddenly discovering mathematical analysis: the discontinuous series of discrete notes would give way to a differentiated continuum capable of generating entirely new melodic modes and harmonic relationships.

Within this continuous spectrum, Avraamov believed humanity could finally notate and analyze the modal systems embedded in folk traditions across Eurasia. He was convinced that ultrachromatic theory would allow previously elusive intervallic subtleties to be documented and preserved. To test his ideas, he again undertook folklore expeditions throughout the Rostov region and traveled across Kazakhstan, Dagestan, and other parts of the Caucasus and Central Asia, collecting melodies that defied Western tonal categorization. He saw these traditions not as ethnographic curiosities but as evidence of alternative tonal logics suppressed by European standardization.

Among early pioneers of microtonality, Avraamov was distinctive in pursuing the erasure of boundaries between pitch-based harmony and the spectral fabric of sound itself. He imagined ultrachromatic instruments not simply as tools for accessing new scales but as mechanisms capable of additive synthesis, constructing sound from its component overtones and thereby aligning musical practice with acoustic science.

Avraamov understood that theoretical arguments alone would not suffice; he sought validation through field research, pedagogy, and practical experimentation.After one year since the revolution, a new idea had formed in his mind, one that would grow to become his defining work, and bring his sonic utopianism into the public sphere on an unprecedented scale.

Writer Anatoly Mariengof, in his memoirs My Century, My Friends and Girlfriends, recalled that on the first anniversary of the October Revolution, Avraamov proposed conducting a Heroic Symphony performed not by an orchestra but by the whistles of factories, plants, and locomotives across Moscow. He pledged to retune and coordinate these industrial instruments with authorization from the Council of People’s Commissars, and he submitted the idea to Lunacharsky. “That would be magnificent!” said the People’s Commissar of Education. “And it would be perfectly in keeping with this great occasion… I will immediately report your proposal to Comrade Lenin… But, I confess,” Lunacharsky added hesitantly (he reportedly had a difficult time saying no to Avraamov), “I confess, I’m not entirely sure Comrade Lenin will agree to your brilliant project. Vladimir Ilyich, you see, loves the violin and the piano…”

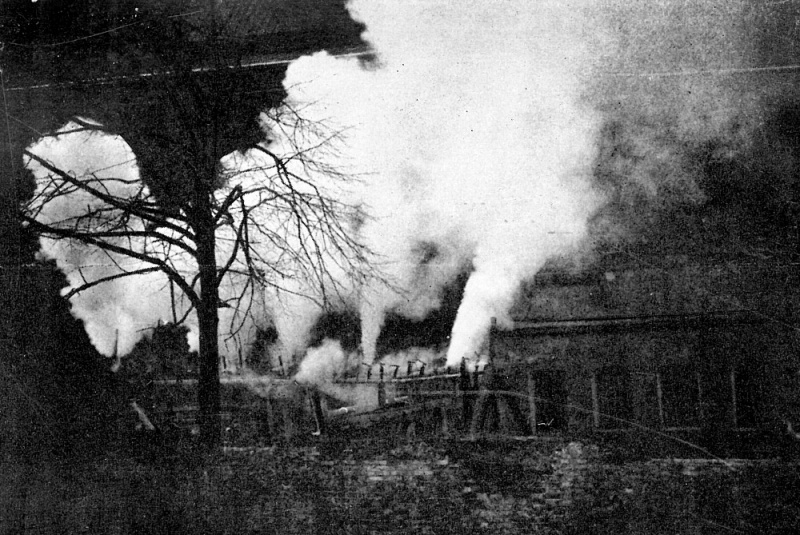

In response, Avraamov derided the piano as an “international balalaika,” an instrument designed to reinforce the constraints of equal temperament. His dislike of the piano was possibly even further intensified by this response. Some years later, he submitted a new proposal to Lunacharsky suggesting the burning of all pianos in Russia, viewing them as symbols of a tonal regime that had distorted human hearing for centuries. The proposal, clearly, was not signed. He likewise argued that traditional orchestral instruments and repertoire should be discarded to make way for newly invented instruments in addition to a ultrachromatic musical language. These incendiary proposals ignited fierce debates in the music press at the time.

Although such radical measures were never implemented, and could hardly have erased centuries of musical heritage, the underlying ideas endured. Quarter-tone and microtonal approaches later re-emerged in the works of post-war composers such as Alfred Schnittke, Eduard Artemiev, Edison Denisov, and Sofia Gubaidulina, confirming that the questions Avraamov posed about tuning, perception, and the structure of sound would remain central to modern music. In Avraamov’s worldview, ultrachromatic theory was not an esoteric technical exercise but a pathway toward a new auditory consciousness, one aligned with socialist internationalism, science, global musical diversity, and the sonic realities of modern life. However, in the moment, the idea of a symphony on a grand scale using elements of the city itself took on a new precedence for Avraamov.

It was during these Civil War years that he began testing ideas that would culminate in his most famous work. In 1919, his time in Nizhny Novgorod included what he later described as a “rehearsal” for a future large-scale industrial composition, an early precursor to the Symphony of Sirens, though the work was not realized in its entirety. Throughout this period, Avraamov treated cultural production as a form of political infrastructure. Lectures, publications, and musical organization were designed to reach workers and soldiers directly, bypassing the bourgeois concert hall in favor of accessible, collective forms of participation. This project would be no different. Though documentation from this performance does not seem to have survived, it is known that the experience gave him the organizational experience needed to attempt the work again.

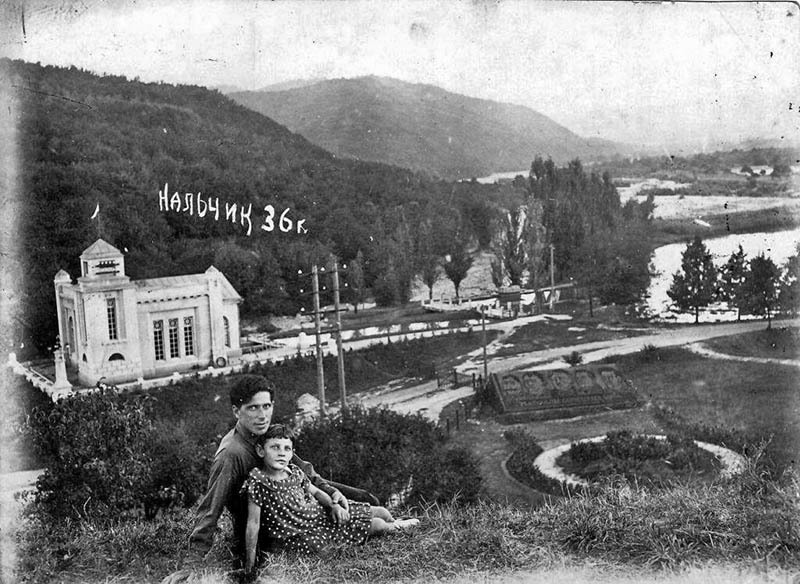

As the years went on, Avraamov moved further and further away from the center of Soviet power, mostly in service of his interest in discovering folk music traditions and due to his strained relations with Soviet authorities in the midst of the civil war. In 1921 Avraamov was appointed head of the arts department in Dagestan, a posting that quickly exposed the limits of revolutionary cultural policy when it collided with deeply rooted local traditions. He began with a campaign consistent with his broader crusade against the musical past, a program involving the confiscation and planned destruction of pianos from wealthy and respected Dagestani households, instruments he regarded as symbols of bourgeois culture and the despised tempered system. The move provoked immediate resentment. Resistance from the community forced him to abandon direct intervention and redirect his efforts toward folklore expeditions in Dagestani villages, where he hoped to document indigenous musical practices and, in keeping with his theories, uncover evidence of alternative tonal systems.

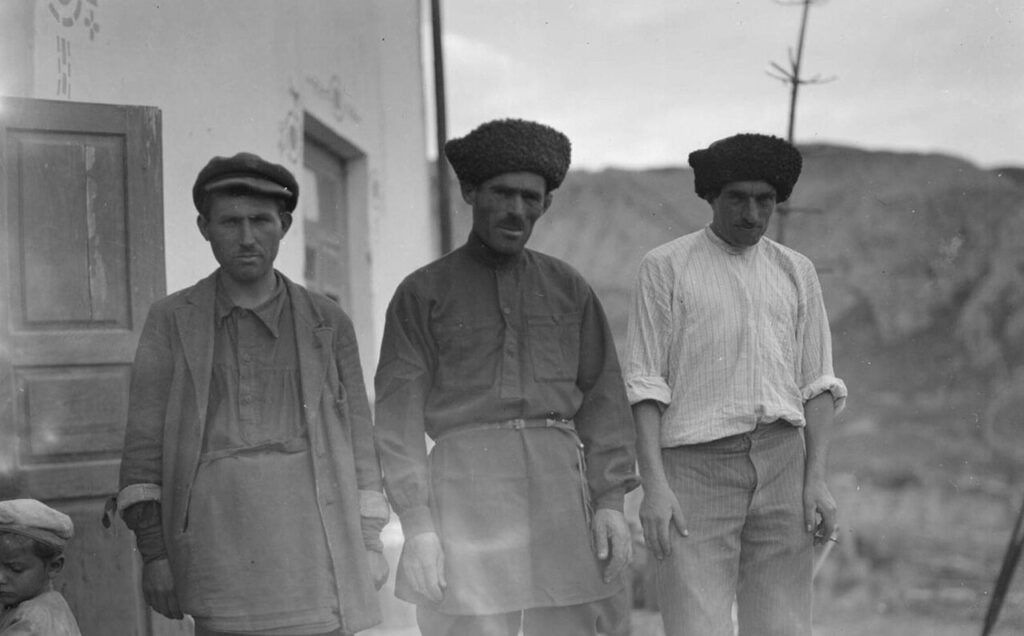

Even this approach met hostility. Villagers viewed the outsider, a political functionary and self-proclaimed music revolutionary, with suspicion. Avraamov responded with theatrical ingenuity. He sought the assistance of a local mullah, who issued him a document with the following text: “The bearer of this document, Arslan Ibrahim-ogly Adamov, was born a Muslim. However, he lived and studied in Russia for many years, and therefore has a poor memory of the language and customs. He should not be held accountable if he says or does something incorrectly; on the contrary, he should be helped in everything and taught if he doesn’t know anything…”

Reinvented once again, Avraamov shaved his head, grew a mustache, dressed in national costume, and traveled under his adopted identity. The transformation proved remarkably effective. Villagers welcomed him into their homes, seated him in places of honor, and offered food and hospitality; musicians performed for him, allowing him to observe and record local traditions at close range. Behind the convivial facade, however, he continued political work: he campaigned for the communists, scheduled party meetings to coincide with Friday prayers in order to divert attendance from the mosque, and, in an effort to maintain credibility, even covered the walls of the local club with quotations from the Qur’an.

The strategy eventually backfired. Reports of his contradictory behavior reached authorities in Makhachkala, prompting a commission of party officials to investigate. He was accused of duplicity, stripped of his party card, and reportedly threatened with execution. As in several earlier episodes of his life, Avraamov avoided the worst outcome only by fleeing, leaving behind another region where his personal theatrics had collided with volatile results.

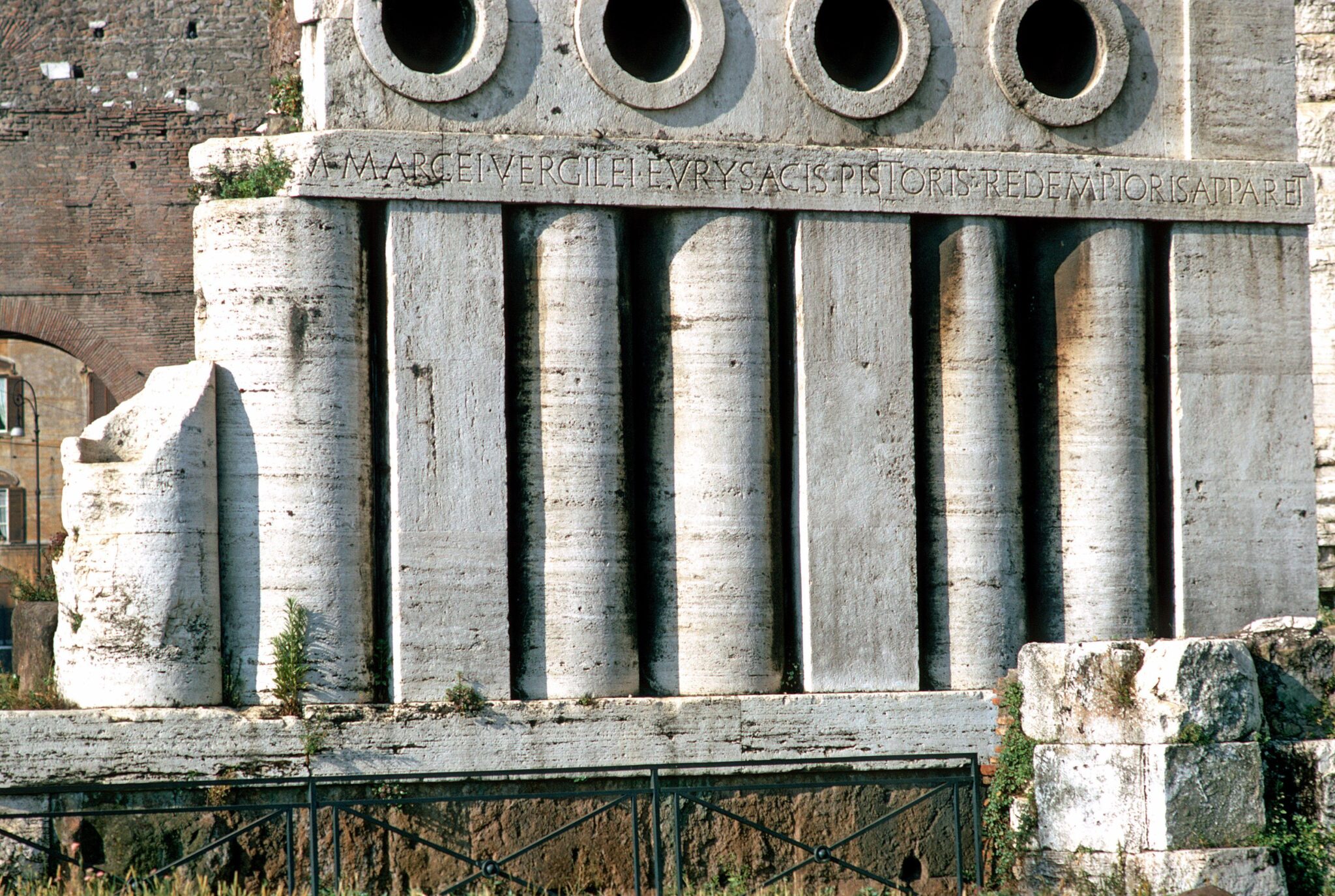

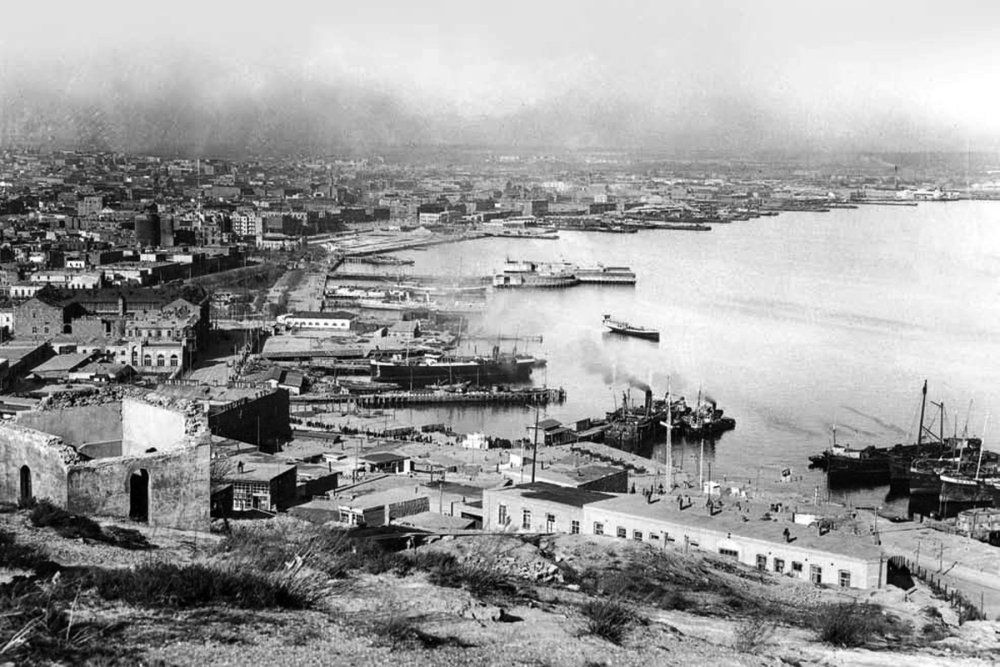

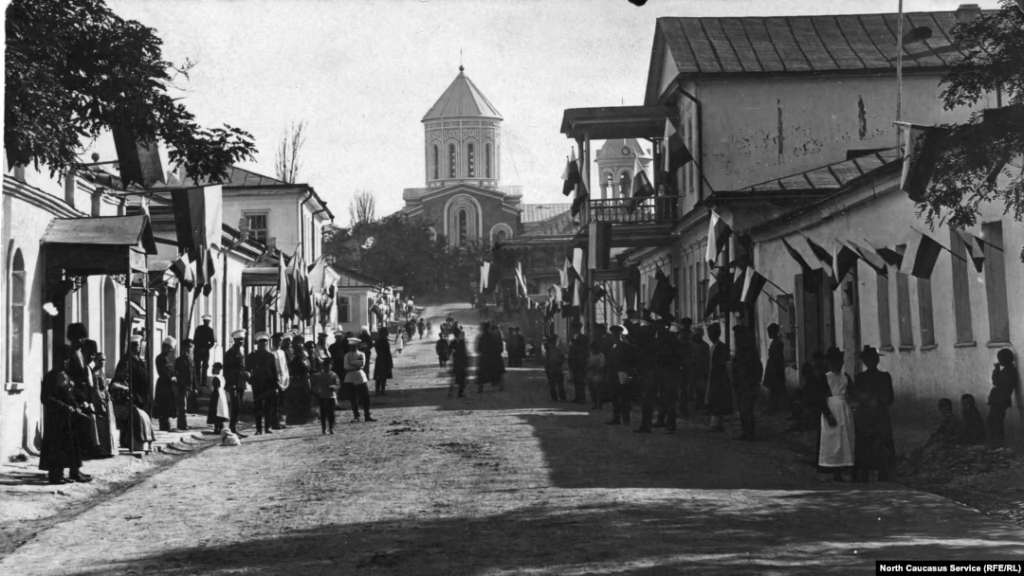

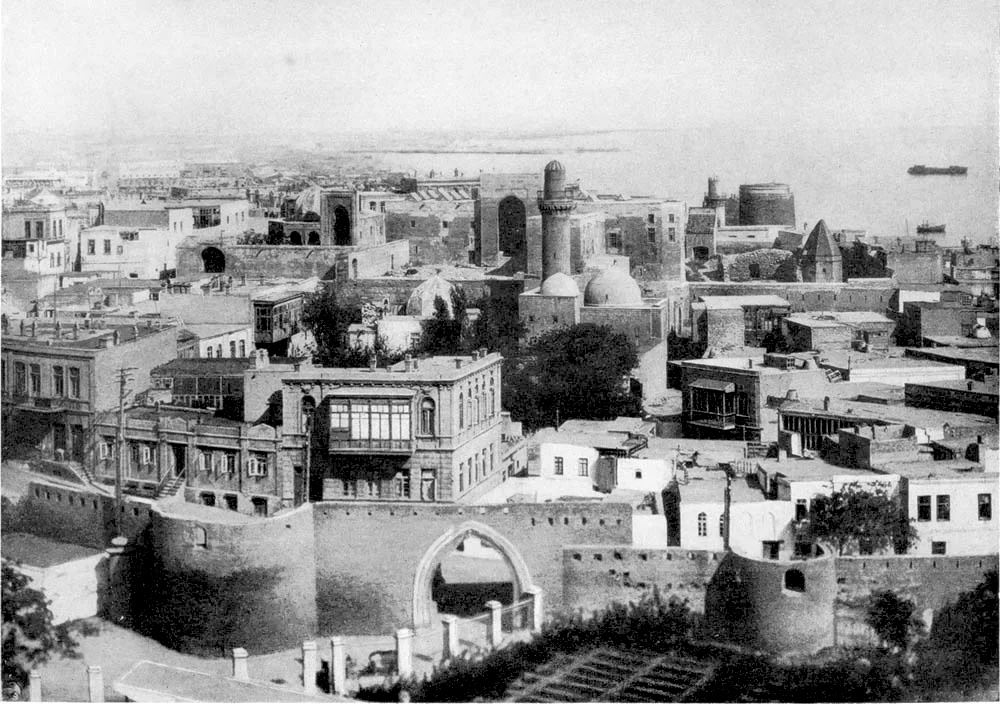

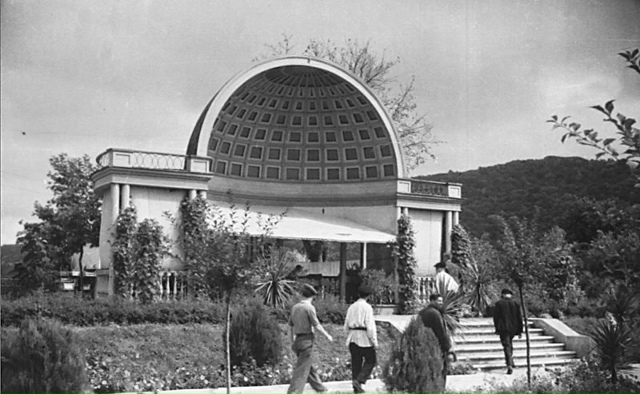

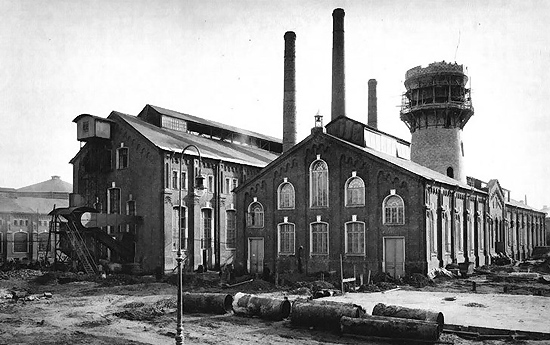

Chased out of Dagestan, he found himself in Azerbaijan, living under his latest assumed identity and working as a laborer in an oil field. Even in this precarious exile, his technical ingenuity distinguished him. He proposed practical improvements that significantly streamlined workflow at the enterprise, drawing the attention of supervisors. Recognized for both his intelligence and organizational ability, he was transferred to Baku to work in his specialty within the arts department. It was in this rapidly industrializing Caspian port city that the Symphony of Sirens would first be realized.

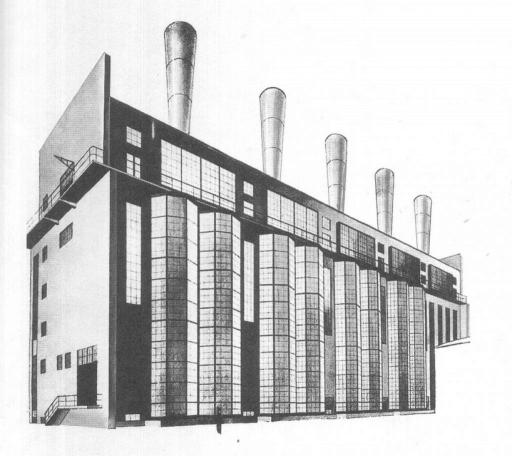

Now in its fifth year, the anniversary of the October Revolution was marked on November 7, 1922, by Avraamov’s staging of his most famous work, the Symphony of Sirens, in the port town of Baku. For this undertaking, Avraamov worked with choirs numbering in the thousands; foghorns from the entire Caspian flotilla; two artillery batteries; full infantry regiments; hydroplanes; twenty-five steam locomotives and whistles; and every factory siren in the city. He also devised a portable instrument specifically for the event, a machine which he called the Magistral: an ensemble of twenty to twenty-five tuned steam whistles calibrated to the pitches of “The Internationale,” “La Marseillaise,” and “Varshavianka.”

Avraamov did not conceive the work as a spectacle for passive spectators. Instead, he intended the active participation of the populace, whose exclamations and singing would merge into the sonic mass, unified by a shared revolutionary will. His reflections on the potential of music, and on the environmental sounds that shape collective consciousness, help clarify the ultimate meaning of the Symphony of Sirens:

“Collective work, from farming to the military, is inconceivable without songs and music. One may even think that the high degree of organization in factory work under capitalism might have ended up creating a respectable form of music organization. However, we had to arrive at the October Revolution to achieve the concept of the Symphony of Sirens. The Capitalist system gives rise to anarchic tendencies. Its fear of seeing workers marching in unity prevents its music being developed in freedom. Every morning, a chaotic industrial roar gags the people. … But then the revolution arrived. Suddenly, in the evening — an unforgettable evening — a Red Petersburg was filled with many thousands of sounds: sirens, whistles and alarms. In response, thousands of army lorries crossed the city loaded with soldiers firing their guns in the air. … At that extraordinary moment, the happy chaos should have had the possibility of being redirected by a single power able to replace the songs of alarms with the victorious anthem of The Internationale. The Great October Revolution! — once again, sirens and work in the cannon whole of Russia without a single voice unifying their organization.”

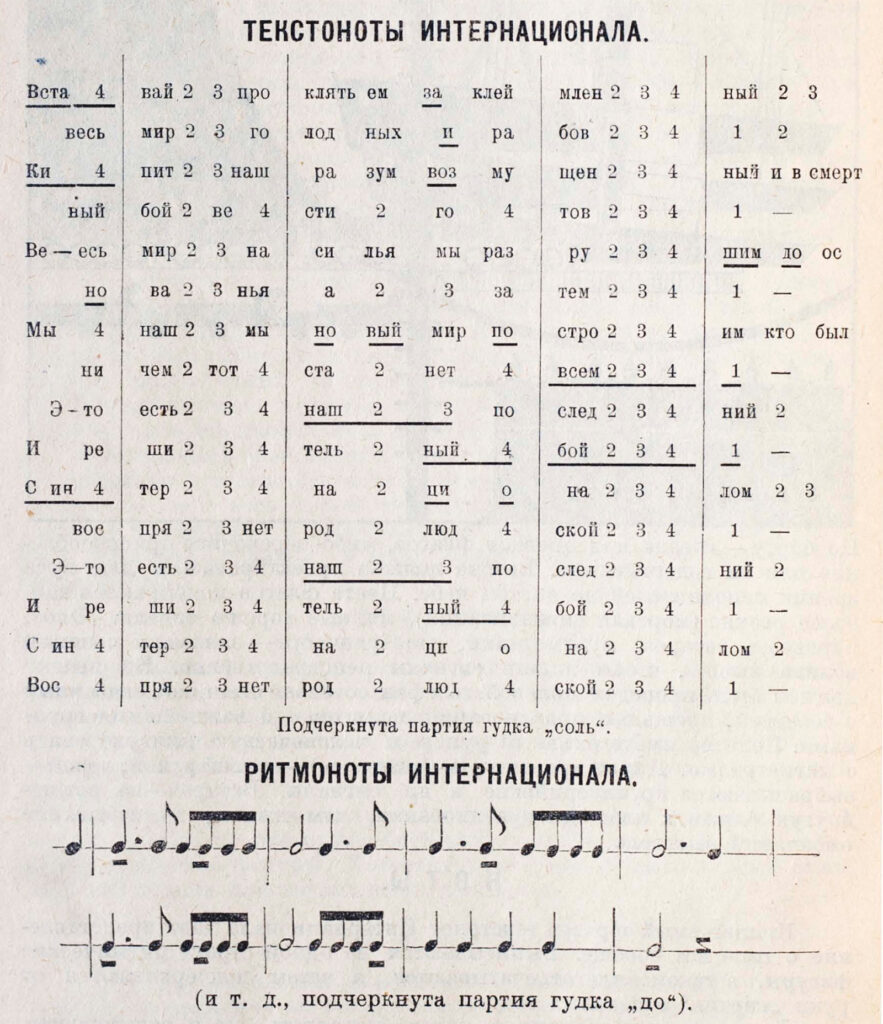

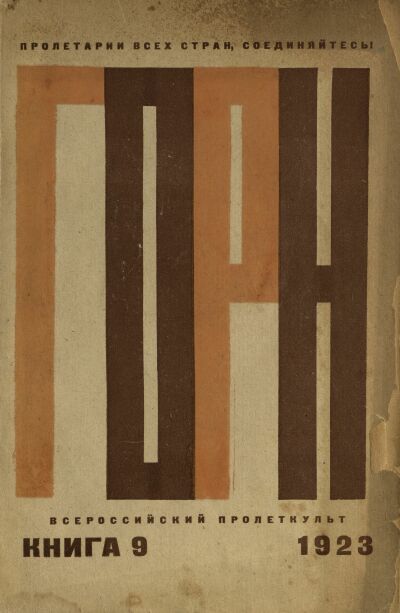

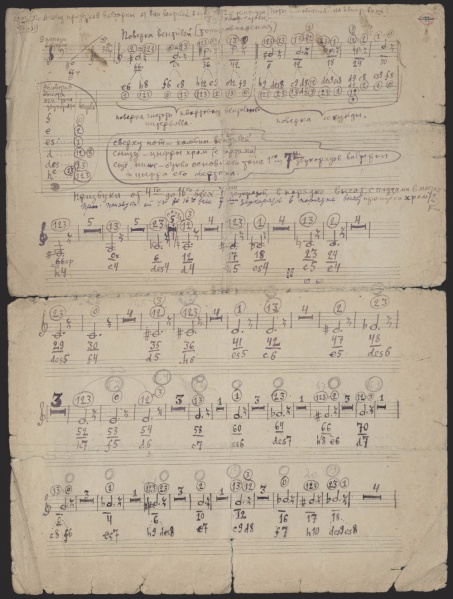

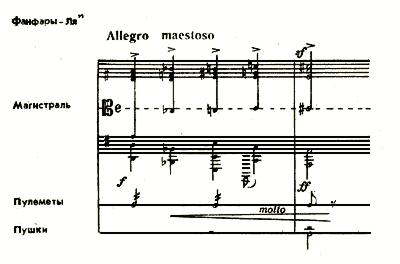

The composer himself later set down detailed instructions for the proper realization of the “Symphony of Horns.” These guidelines were published after the second staging, a year later, in “Gorn,” the journal of the All-Russian Proletkult. At the center of this unconventional orchestra stood the horn mainline, what Avraamov regarded as the essential melodic engine of the work. He insisted that the most effective configuration was mobile, specifically in the form of a locomotive car. The mainline consisted of several dozen cylindrical horns mounted along a single steam pipe. Pitch was adjusted by shortening the air column, and the total number of tones corresponded to the melody of the Internationale, which Avraamov quoted directly; additional pitches were added for harmonic support. At the same time, he left open the possibility that an expanded set of tones could allow performers a degree of creative latitude. In the 1923 article published in Gorn, Avraamov described the device in practical, almost engineering terms:

“The setup of the Magistral is very simple: 20 to 50 horns (usually cylindrical, as they are easier to adjust) are screwed onto a common pipe. The pipe is shaped according to the installation location: straight, semicircular, two- or three-legged—it makes no difference from a sound standpoint. It’s important that the steam supply be centered, and that drain cocks or valves be installed at the ends to drain water before playing—otherwise, water will be ejected through the horns’ valves, and the rhythmic precision of the performance will be lost.”

This steam-whistle organ, known as the Magistral, functioned as a mobile instrument through which Avraamov proposed to perform the symphony, incorporating locomotive whistles specially tuned according to his ultrachromatic pitch concepts. An electrified musical keyboard controlled electric valves that activated the whistles; this control interface was to be mounted in the locomotive driver’s cabin. In the early 1920s, factory sirens, ubiquitous and unmistakably modern, were considered a revolutionary replacement for “bourgeois” church bells and became central components in the construction of new sound machines.

Sirens were conceived as a distinct instrumental group within the work. Their pitches could sound independently, cluster into chords, or glide in parallel and contrary motion, producing shifting harmonic masses rather than fixed tonal relationships. Their behavior contained an element of contingency, dependent on performer skill and timing. With sufficiently adept operators, he suggested, sirens might eventually assume harmonic or melodic roles, but this remained a speculative frontier: humanity was only beginning to grasp the principles governing their “specific harmony and melody.”

From Avraamov’s own descriptions, a clear hierarchy of sound sources emerges. The principal instruments were the Magistral and the individual whistles of factories, naval vessels, and other locomotives. The Magistral, together with mass choir and brass band, carried the melodic material. Artillery batteries and machine guns supplied rhythm. Bells were included in this latter category: “Bell tolling—alarm, funeral, and jubilant—is used in the appropriate episodes, without regard for the harmonic concept,” Avraamov wrote.

Distributed groups of stationary whistles from oil fields, factories, docks, depots, and steam plants were tuned into “compact harmonies” and deployed to create vast spatial sound images. Cannon salvos signaled their entrances, and the timing of these signals had to account for acoustic distance: the sound of the signal gun and the response of the whistles needed to align at the celebration square. During the performance of the Internationale, distant whistle groups remained silent because the cannon was repurposed as a bass drum. Machine-gun fire simulated drum rolls and executed complex rhythmic figures, while blank volleys and rapid bursts provided dramatic sonic punctuation. Yet Avraamov did not totally abandon traditional expressive means: in addition to bells, choral singing remained integral to the work’s massed sonic texture.

Automobiles were also incorporated into the sonic plan. If enough vehicles with tunable horns were available, the composer envisioned forming an independent timbre-harmonic group from them. More often, however, cars were treated as sources of noise texture, alongside the low passes of seaplanes and other aircraft, whose engines contributed broad, droning layers to the urban sound field, in his words to “generate stunning effects that create a stunning emotional impact.” Yet these elements were valued as much for their visceral force as for any musical precision.

The presence of heavy weaponry, startling to later observers, had practical logic. “Because of the large area of distribution of the factory sirens,” he explained in the article, “it is necessary to have at least one heavy gun for signalling purposes with the capacity to shoot live cartridges. (Shrapnel is not suitable for this – bursting off in the air is most dangerous and gives a second explosion sound, which can confuse the performers.)”. Field artillery doubled as a “large drum,” and experienced machine gunners, shooting live belt-fed ammunition, “not only simulate a drumbeat, but also beat out complex rhythmic figures. A gun shooting with blank cartridges as well as gunfire with frequent packs are good for vivid scene sounds.””

Coordination of such a dispersed orchestra required a purpose-built conducting tower erected at an elevated site near the performance center. Avraamov specified that “the simplest device is a pair of telegraph poles joined at the ends with a ‘Swedish mast.’ At the top is a platform with a barrier,” with sockets for signal poles or a rope mechanism for hoisting flags. The structure had to provide a clear line of sight under open sky, while marine-style signal flags, chosen for maximum visibility, carried visual cues to the fleet, locomotives, artillery batteries, machine-gun crews, and motor vehicles positioned so they could see the signals directly. A field telephone station linked the tower to the battery, celebration area, firing range, and key performer groups; a powerful megaphone and direct human relays provided redundancy. Conducting duties were divided physically: “Conducting (metric) is done with the right hand; artillery and other signals are fired with the left,” and the batteries were placed closer to the celebration zone than the tower to prevent delays in firing.

From this tower, Avraamov conducted an environment rather than an ensemble, integrating steam, steel, combustion, and human voices into a unified acoustic ritual. What appeared chaotic was in fact a rigorously engineered system designed to reorganize the industrial soundscape into collective music, an auditory architecture intended to replace the fragmented noise of modern industry with a coordinated sonic emblem of revolutionary society.

Avraamov even anticipated the need for rehearsal and replication. The work could be practiced indoors using small single-tone instruments such as harmoniums, clay whistles, children’s tin whistles, standing in for industrial horns. The surviving materials provided to performers of the Symphony reveal how radically the work departed from conventional notation. Instead of staff notation, Avraamov used the text of Internationale and other songs included in the work with syllables underlined to indicate timing and duration. These “text notes” coordinated sonic events across the dispersed ensemble, translating a revolutionary anthem into a temporal grid for industrial sound.

The concept was never intended as a singular spectacle confined to one city. As Avraamov urged, “We want every city with a dozen steam boilers to organize a worthy ‘accompaniment’ to the October celebrations … and we provide here instructions for organizing a ‘Symphony of Sirens’ adapted to various local conditions. After a successful experiment [in Baku], this is no longer difficult: all that is needed is initiative and energy” The work was thus conceived as modular and reproducible, capable of being scaled and reinterpreted according to local industrial resources and urban acoustics.

It may seem surprising that Arseny Avraamov, a drifting, restless figure more bohemian engineer than disciplined party functionary, at times disgraced or sidelined elsewhere in the Soviet Union, was granted the resources and official permission necessary to realize a project on the scale of the Symphony of Sirens. His technical accomplishments and reputation as an innovator certainly lent credibility, yet the broader climate of the early post-Revolutionary years was equally decisive. The period was marked by a volatile openness to experimentation, especially where art intersected with industry, labor, and mass mobilization. The revolutionary project aimed at total social integration: the unification of workers, factories, communication systems, and civic space into a single collective organism. Within such a framework, the idea of using an entire city as a musical instrument did not appear absurd but symbolically precise. Moreover, the conceptual foundations of the symphony were not Avraamov’s alone; writers, theorists, and cultural organizers had already articulated parallel visions of industrial sound as a collective artistic medium.

Even while stationed far from the principal centers of Soviet avant-garde activity, he followed developments closely, absorbing ideas circulating through Proletkult networks, futurist theory, and the emerging aesthetics of industrial modernity. These encounters sharpened a vision that had been forming for years: a sonic event constructed not from orchestral instruments but from the sound infrastructure of modern life. In this period of distance and observation, the concept that would become the Symphony of Sirens first cohered into a practical form.

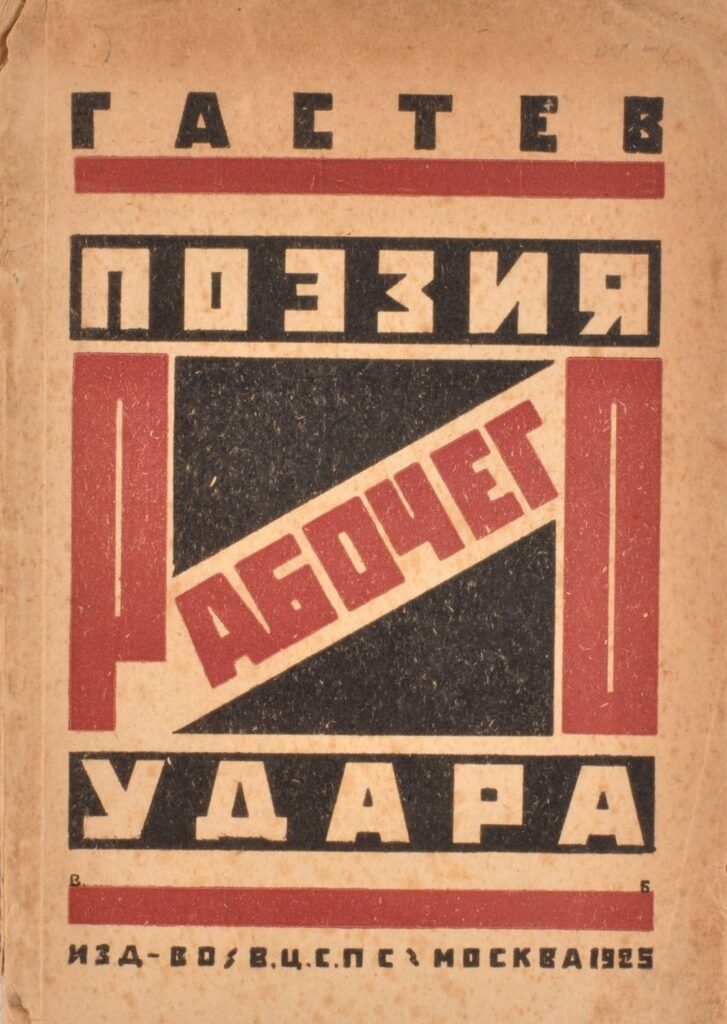

One influence stands beyond dispute. Throughout his manifestos and programmatic writings, Avraamov repeatedly invoked the poet Aleksei Gastev as both inspiration and proof of concept. In his article A New Era of Music, he reproduced in full “Order 06” from Gastev’s A Packet of Orders, the concluding cycle of Gastev’s Poetry of the Worker’s Strike, published only a year before the Symphony of Sirens premiered in Baku.

Avraamov explicitly acknowledged that he imagined the music of the new century under the influence of Gastev’s poetry, reproducing the following text:

“Asia — all on the note D.

America — a chord higher.

Africa — B‑flat.

The Radio Conductor.

Cyclone cello — solo.

Forty towers — with a bow.

Orchestra along the equator.

Symphony along the parallel 7.

Choruses along the meridian 6.

Electric strings to the center of the earth.

Sustain the globe of the earth in music

for the four seasons.

Sound in orbit for four months pianissimo.

Make four minutes of vulcano-fortissimo.

Cut off for a week.

Burst into vulcano-fortissimo crescendo.

Maintain on vulcano for six months.

Start from scratch.

Collapse the orchestra.”

The work reads as a brief set of instructions (not unlike Avraamov’s) for a symphony performed on a planetary scale, seemingly only a few steps higher in order of magnitude following the Symphony of Sirens. Another text by Gastev, “Manifestation” (published in 1918 in the Proletkult journal The Future), reveals even more clearly the conceptual roots of Avraamov’s later sonic spectacles. The passages read less like metaphor than an operational score for industrial sound:

“Orchestras! Orchestras!” they shout from the towers.

Two hundred hand-picked strongmen—boilers—locomotives step forward, tune the chorus of horns, the chorus strikes instantly, and the sound salvos rush ahead of the division.

Music intended for cities, departments, states…

The trumpets stretch out.

Their sullen pride grows.

The fiery stations rage.

The giant searchlights flare up instantly.

Then they go out.

The horns cease.

Signal silence…

Only two minutes. Minutes, like an era.

— An explosion of light and music.

And a hurricane of work begins.

The musical boilers thunder “Green Shoots.”

— A thousand-pipe locomotive—our greetings!

— Pipes, smoke. Your foul labor is not wasted. Smoke.

— Boilers, continue your anthem.

— Composers’ Workshop! — A symphony to the cannons immediately!

Boilers, thunder “Victory!”

Thunder “Victory,” but quietly transition to “Alarming.”

— Boilers, “Victory!”

Pipes, march!

Ceremonial!

Smoke to the heavens! Hands, wave your black hands across the earth.

Factories, dance in a circle!

Strike the oil tanks,

Strike with steam hammers!

Demonstrators, take a rest.”

From Gastev’s poem Manifestation, he borrowed the slogan “Music intended for cities, departments, states.” Gastev is also credited with introducing the word symphony into the context of industrial modernity; as early as 1919 he called for the creation of “a symphony of workers’ strikes and the clatter and roar of machinery.”

Gastev’s grand, utopian poetic universe, constructed from the hyperbolic musicality of industrial civilization, aligned closely with Avraamov’s own thinking. Both men shared an unusual synthesis of technical rationalism and propagandistic fervor, treating art not simply as aesthetic expression but as a tool for reorganizing perception, labor, and collective life. Their works often functioned as blueprints as much as artistic statements, combining engineering logic, political urgency, and visionary spectacle.

Here the industrial city becomes orchestra, instrument, and performer. Sirens, boilers, locomotives, searchlights, smoke, and human labor merge into a coordinated sonic and visual mass event—the precise logic Avraamov would later attempt to engineer. What Gastev articulated poetically, Avraamov sought to render operational. Such ideas were widespread in the revolutionary cultural atmosphere. In 1918, poet Boris Kushner’s manifesto The Revolution of Materials, published in the Proletkult journal Our Way (which also printed several of Avraamov’s articles), declared:

“The music of the future will have to be performed for vast public gatherings. Perhaps for entire cities at once … Where there is a need for sounds that can be heard in the conditions of urban life—on the streets, in workshops, at public festivals attended by thousands—there one must resort to special apparatus… There is no risk in predicting that modern musical instruments … will not long remain in the practice of socialist music.”

Such statements demonstrate that Avraamov’s project was not an isolated eccentricity but part of a broader reimagining of sound, space, and collective experience. The earliest proletarian holidays had already revealed how radically the function of music was changing in public life. Within this climate, permission for the symphony became both politically symbolic and culturally logical. By 1922–23, while preparing and refining the work in Baku, Avraamov taught at the Communist Party High School and worked as a cultural organizer at military courses for the Central Committee of the Azerbaijani Communist Youth Union in Armavir. These institutional roles placed him at the intersection of propaganda, education, and mass spectacle, precisely the terrain on which the Symphony of Sirens would unfold.

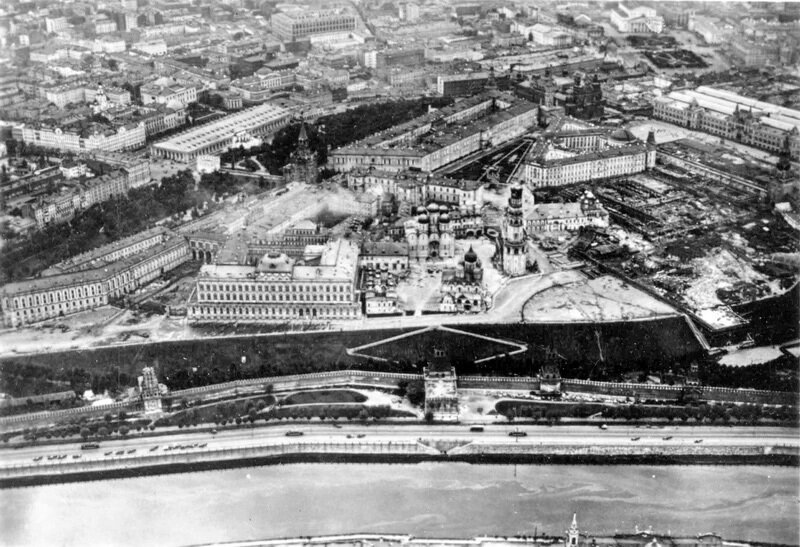

On the morning of the fifth anniversary of the October Revolution, November 7, 1922, the port of Baku was mobilized with the precision of a military operation. Orders specified that by 7:00 a.m. every vessel belonging to the Gokasp (State Caspian Shipping Company), Voenflot (Military Fleet), and Uzbekokaspiy (Caspian Sea Security Directorate) fleets, including small steam launches, assemble at the railway pier to receive musicians and instructions before taking position near the customs piers. The destroyer Dostoiny, equipped with its set of steam whistles, was stationed ahead of the formation opposite the signal tower, with smaller vessels arrayed nearby. By 9:00 a.m. the fleet was to be fully deployed. At the same hour, all available locomotives, shunting engines, local service trains, armored trains, and even those out of repair, were ordered to the pier, transforming the harbor and rail yard into a unified acoustic apparatus.

Human forces arrived in parallel. Cadets from the 4th Armavir Courses, students of the Higher Party School, participants from military training programs, students of the Azerbaijan State Conservatory, and professional musicians were required to report no later than 8:30 a.m. By 10:00 a.m. infantry, artillery batteries, machine-gun units, armored vehicles, and motor transport took up their assigned positions in accordance with the garrison order, while airplanes and seaplanes stood ready. Signalmen were instructed to sound district, station, and dock horns by 10:30 a.m., and even the traditional midday cannon was cancelled to make way for the carefully scripted sonic sequence that would follow.

What unfolded was not merely a performance but a programmed “sound picture of alarm, the unfolding battle, and the victory of the International Army,” as outlined by Avraamov in the newspaper Bakinsky Rabochy (The Baku Worker). The scenario began with the “Alarm” After the first salute from the roadstead around noon, alarm horns sounded from the Zykh, Bely Gorod, Bibi-Heybat, and Bailov districts of the city. Subsequent cannon shots triggered successive layers: dock horns, factory sirens of the Chernogorod district, naval signals, and the movement of artillery cadets led by a brass band playing Varshavyanka. With the eighteenth cannon, city factories joined and seaplanes took off; by the twentieth, railway whistles and remaining locomotives entered while machine-gun units and infantry received signals directly from the conductor’s tower. The siren built to a maximum intensity before ending with the twenty-fifth cannon and an “all clear” signal.

The second part of the work, the “Battle” began with a triple chord of sirens announcing the transition. Seaplanes descended, the crowd at the pier shouted “Hurrah!”, and at a signal the Internationale sounded four times. During the second half-stanza, the combined brass band entered with La Marseillaise. On the melody’s first repetition the entire square joined in chorus, singing all three stanzas. Throughout this section, factory whistles and railway signals fell silent, allowing the revolutionary hymn to dominate the acoustic field.

Lastly came the “The Apotheosis of Victory.” A general solemn chord sounded across the city, accompanied by volleys and bell ringing for three minutes, followed by a ceremonial march. The “Internationale” was repeated twice more during the final procession, and after the third performance a final unified chord of sirens and horns sounded across Baku and its districts. At least, that was the intended operating procedure as outlined by Avraamov.

Execution of the event fell under the responsibility of military and port authorities as well as Azneft (State Association of Azerbaijan Oil Industry) and participating educational institutions. The scale guaranteed technical challenges, yet according to accounts cited by scholar Sergei Rumyantsev, the “orchestra” did indeed carry out its instructions and the anniversary celebration proceeded as planned. However, it was not executed perfectly. One description of the event appears in the memoirs of composer Lidiya Ivanova, daughter of Symbolist poet Vyacheslav Ivanov, published in 1992. Writing about her time in Baku, she described the scene: “At the solemn hour, a large group of people gathered to listen, but the symphony fell apart. A cannon was heard, then a whistle, a cannon, another whistle, and suddenly the cannon fell silent. The sirens also fell silent, then each began to emit its own sound at random, first singly, and then all together, roaring at the top of their lungs. It turned out that a ship had appeared on the horizon, and the authorities had forbidden the cannon to fire.”

The technical problems were hardly surprising given the unprecedented scale of the undertaking. Coordinating industrial sirens, artillery, ships, locomotives, aircraft, and massed performers across an industrial port city was a logistical experiment as much as an artistic one. Relying largely on Avraamov’s own publications, Rumyantsev’s optimistic assessment stands in tension with the total silence of the local press after the fact, a silence also noted by Russian avant-garde scholar Andrei Krusanov. For many later commentators, the absence of coverage suggests not triumph but confusion, indifference, or disappointment.

The difficulties were not only technical but due to a fundamental disconnect with the work’s intended audience. Avraamov’s premise rested on the belief that horns, cannon fire, and industrial sirens would be as legible and emotionally resonant to the proletarian public as revolutionary songs, brass bands, or church bells. In practice, audiences unaccustomed to avant-garde experimentation heard something very different: songs were obscured by mechanical roar, tonal relationships dissolved in open air, and the industrial sound mass registered less as music than as pure noise. Even had the coordination been flawless, the work would likely have encountered the same sociological barrier faced by Futurist and avant-garde art more broadly when addressed to mass audiences. Popular taste tends toward the familiar; just as with abstract visual art, noise-based and microtonal experiments were intelligible mainly to a small circle of avant-garde practitioners.

Despite contested reception, the performance represented the fullest realization of Avraamov’s urban symphonic concept to date. The collaborative force of all parties involved served to transform Baku into a testing ground for a new form of civic music. The experiment, whether viewed as triumph or failure, demonstrated the feasibility of organizing an entire city as an instrument and brought Avraamov renewed institutional respect, encouraging his return to the centers of Soviet power with proof that the industrial soundscape could be mobilized as revolutionary art. The work was now scheduled for another large-scale presentation in exactly a year, this time in Moscow.

In the background of this performance and its preparations, Avraamov’s personal life was just as unstable and improvisational as his artistic projects. While in Azerbaijan he adopted the surname Adamov and met a new partner, Eva. The period surrounding the Symphony of Sirens coincided with a new domestic chapter: he and Eva would have a son, also named Arseny, born nearly at the same time as the second performance of the Symphony of Sirens.

Eva was neither his first nor last wife. During an earlier posting in Kazan he had entered another marriage, and later in Rostov he became involved with a pianist named Revekka Zhiv, whom he later described as embodying the same essential image he would see in all of his wives to come. Contemporary accounts suggest that he possessed a strong personal magnetism: despite frequent conflicts with administrators and authorities, he attracted devoted friends and followers, particularly women. Over time he maintained multiple wives who reportedly coexisted without open conflict. He framed this arrangement as a deliberate social experiment, free of jealousy or possessiveness, and claimed it represented a reformed model of marriage consistent with his broader revolutionary utopian thinking.

Physically, he cultivated the image of unusual endurance and strength. A gymnast and capable rider from youth, he reportedly remained athletic well into middle age. In his late fifties he was said to still be able to perform full rotations on a horizontal bar, and while near sixty he gathered mushrooms in forests outside Moscow while moving on his hands. Naturally, he fathered numerous children. Although not all survived the war years, one son, Herman, later worked to preserve and promote his father’s legacy, ensuring many of his stories could be told now.

Not everyone who encountered him found him persuasive. Lidiya Ivanova, having also directly encountered him in Baku’s local circles of artists and musicians, described the man as thus: “A musician named Avraamov appeared in Baku. He was a lanky, red-haired enthusiast, seemingly starving. Everyone pitied him, fed him, and listened to his theories. One of the major civic holidays was approaching, and Avraamov conceived the idea of celebrating it with an unprecedented, grandiose, national symphony … Avraamov declared that, despite the failure, he had never felt greater than when he conducted a cannon with a 60-mile orchestra. Avraamov lived a little longer in Baku on the money he received for his symphony and, having borrowed as much as he could from acquaintances, disappeared from the city, abandoning his wife, whom he had already acquired during this time. His detractors said that he systematically traveled to different cities and then left them, leaving behind debts and a local wife.”

Accounts like Ivanova’s complicate the heroic image. They present a figure who inspired loyalty and curiosity but also frustration: a visionary organizer of sound and spectacle whose ambitions often exceeded the social, technical, and institutional structures available to sustain them.

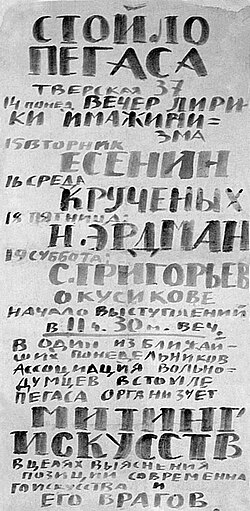

Avraamov returned to Moscow in September 1923 with a reputation that suggested triumph but a personal situation that suggested collapse. He arrived without stable housing or reliable income, drifting between temporary arrangements while attempting to convert notoriety into paid work, mostly continuing to write articles. Nights were often spent at the legendary Pegasus Stall, the poetry café run by Futurists and Imaginists, where sympathetic artists allowed him to eat and sleep on credit. In correspondence with Revekka, he described the arrangement with a particular humor:

“The only advance payment I received from publishers I have spent on an overcoat etc. It was necessary. I eat at the Pegasus Stall — the cafe of the Imaginists — gratis, on account of future blessings, lodging for the night in a separate room — in a word, I am sharing the stable with Pegasus.”

The contrast between visionary ambition and material precarity was stark. Even as he depended on the goodwill of avant-garde circles to survive, he was preparing a second large-scale realization of his siren symphony.

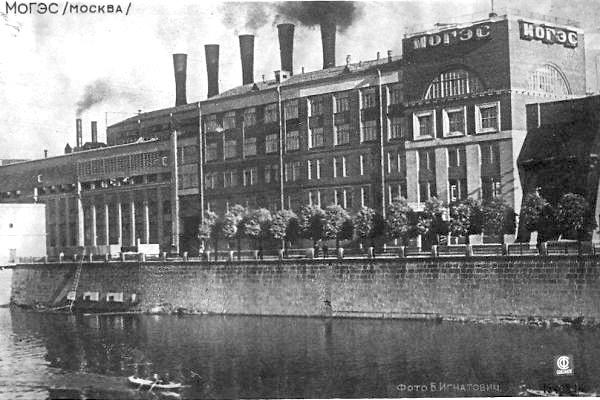

The Moscow version of his masterwork, often referred to as “Symphony in A”, was to be mounted within months following his arrival in the yard of the MOGES (Moscow Association of State Power Plants) Central Thermal Power Station for celebrations marking the sixth anniversary of the Revolution. Conditions proved far less favorable than in Baku although the Moscow version carried personal symbolism. In its title and opening fanfares, Avraamov encoded the names of two women central to his life, his wife Olga and his lover Revekka. Writing to Revekka, he framed the tonal center itself as intimate symbolism:

“Things have settled down at the ‘Sirens’: funds have been allocated for the ‘personnel’ of the organizers and performers—there are no more obstacles. Now, once I’ve found a place for my son, I’ll get to work with all my energy. Olga will work with me … Your symphony’s theme—its tonality—is that both the children and I have always called it ‘A’ … let it be A, the final chord of the theme—the tonic of the entire symphony…”

He had met Revekka in August 1923 during a short stay in Rostov. She came for private piano lessons and found him in an absurd but revealing situation: he owned only one suit, which was being washed and ironed, and he received her naked while waiting for it to dry. By the next lesson he was convinced he was in love; soon afterward he concluded he would have to choose between marriage and flight. True to habit, he chose the latter. By the time he had resurfaced in Moscow a month later, he began sending passionate letters promising great works of art in her name, bearing grandiose and contrived titles such as “Revtractate (Revolutionary Tractate) on Novmuzer. ‘Without Ancestors,’ USSR, 6th year of the first century.” Ever the true believer, he saw the start of the revolution as year zero, even going so far as to rename the months.

During this same period he wrote prolifically (mostly out of economic necessity), contributed to Pravda and Izvestia, and reportedly planned an avant-garde periodical with Leon Trotsky titled Hotel for Travelers to the Beautiful. He received invitations to teach at the Moscow Conservatory and pursued new theoretical writings while continuing to organize the coming performance of his Symphony. Yet the material facts remained unchanged: he still slept in the Pegasus Stall because he had nowhere else to live.

By this point his personal life was as layered as his artistic schemes. The Moscow horns symbolized not only revolutionary spectacle but his emotional entanglements: Revekka in Rostov; Olga working beside him; and another wife from Kazan who suddenly reappeared in Moscow from his past. The composer who sought to unite cities into a single acoustic organism was, in private life, orchestrating a similarly improbable harmony, balancing overlapping relationships, utopian manifestos, irregular jobs, and grand artistic promises while drifting through the capital without a fixed address.

As the anniversary approached, newspapers promoted the event as a “concert of factory whistles” and a “series of numbers on revolutionary themes,” phrases that both attracted attention and quietly misrepresented what listeners were about to encounter. By midday on November 7, crowds poured toward the Moskva River, filling the embankments and clustering along the Bolshoy Moskvoretsky Bridge and Bolshoy Ustinsky Bridge. Artillery pieces lined the riverbanks. Steam locomotives, factory sirens, cannons, and whistles were coordinated across the city, while spectators searched for vantage points from which they could grasp the scale of the promised spectacle. Avraamov himself climbed to the roof of a four-story building so he could be seen from both sides of the river. From this improvised podium he once more raised his colored flags to signal the beginning of the performance.