During the Cold War, access to music in the Soviet Union was tightly restricted by state censorship. Despite the risks, a covert community of music enthusiasts and bootleggers emerged, determined to defy censorship and share the sounds banned by the regime using an unlikely medium: discarded hospital X‑ray film.

Cheap and readily available, these X‑rays were repurposed into records, nicknamed “music on the bones” which were secretly copied, sold, and passed hand-to-hand on the black market. At one point, trading or even listening to these illicit recordings could carry severe consequences. In some cases, bootleggers were sentenced to years in prison. It was a time when the simple act of hearing the music you loved meant risking your freedom.

In the Soviet Union under Stalin, Western music was officially banned out of fear it would corrupt the minds of citizens. The government maintained tight control over music production. Vinyl was scarce, and the raw materials needed to press records, namely polyvinyl chloride and acetate, were heavily restricted. All legal records were pre-approved and came from state-run factories, which primarily produced patriotic anthems, classical compositions, and traditional folk songs intended for community dance halls, also funded and managed by the state. The atmosphere of what was called “working class leisure” was controlled, and only specific partner dances were encouraged. These were often slow and heavily choreographed, leading many younger generations to become increasingly bored with them.

Smuggled Sounds

Following WWII and the beginning of the Cold War, Western nations, particularly the U.S. and Britain, were actively broadcasting jazz and rock and roll into Soviet territory, offering a glimpse of the cultural landscape beyond the Iron Curtain for those fortunate enough to receive their radio transmissions. This is where many Soviet citizens first caught wind of the sensational waves happening in Western music at the time and wanted to hear more of it.

A curiosity needed to be fed, and records were being smuggled into the Soviet Union. While this black-market pipeline began in earnest after WWII, when Soviet soldiers brought back trophy Western records from former axis territories, there were several opportunities to bring in foreign music. Children of high-ranking diplomats had privileged access to foreign goods, which included music, and sometimes rented out their collections to friends while sailors, who had lucrative opportunities to travel to the rest of the world and pick up products which could not be bought back home, also played a key role in transporting music and other contraband back into the country. Additionally, professional smugglers known as fartsovschiki worked the margins, often striking deals to receive goods, including records, from foreign tourists, and turn around and sell them on the black market.

But there still wasn’t enough of it to go around, and supply was much higher than demand. The underground recordings “appeared because Western records that came to Russia through black marketeers were insanely expensive.” says Aleksandr Genis, a Russian-American writer and critic, “When I was a student, a record of, say, “Pink Floyd” cost a hundred rubles, my scholarship as a top-performing student was 45 rubles, and I also received 62 rubles a month working as a fireman. So the cost of one “Pink Floyd” record was equal to my monthly income, which I earned in a far from easy way. Of course, this was an incredible amount of money, few could afford it, hence the “music on the ribs” because it cost pennies. One homemade record cost about a ruble. The recordings were terrible, of very poor quality, but no one complained because there were no others and there was nothing to compare them with.”

New Ways to Use X‑Rays

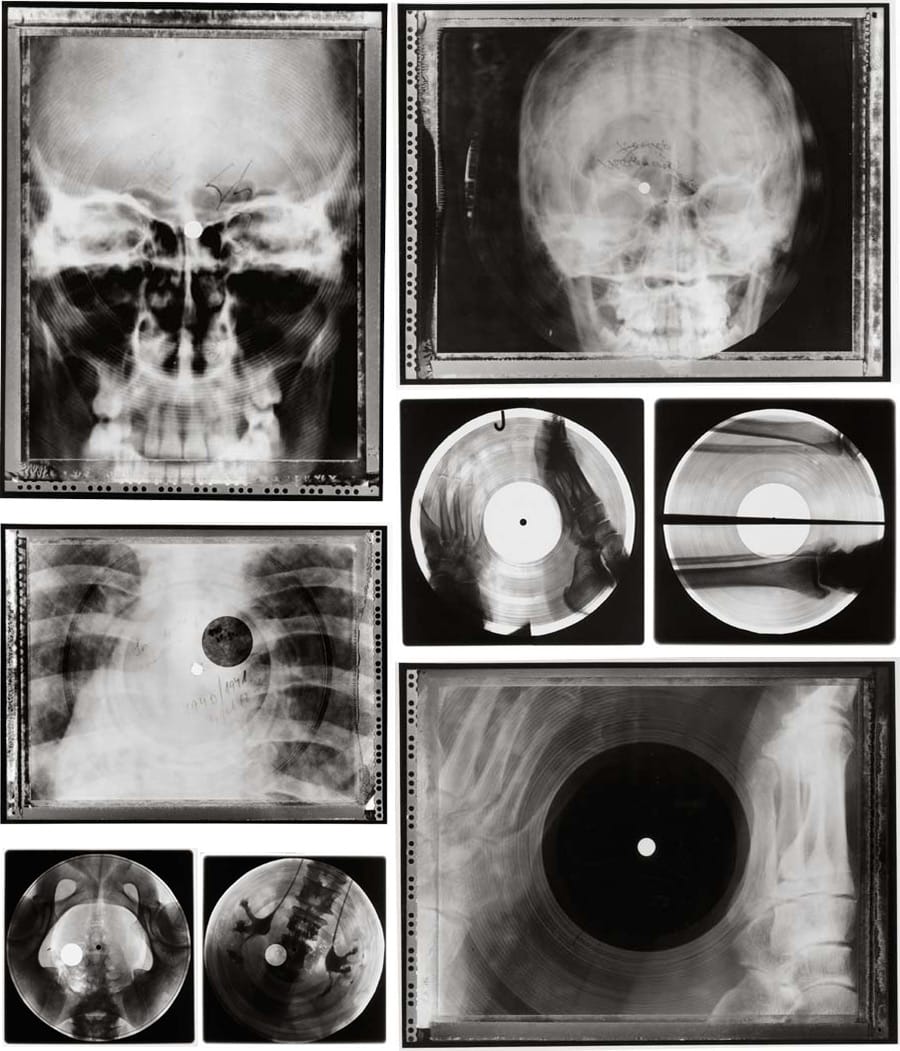

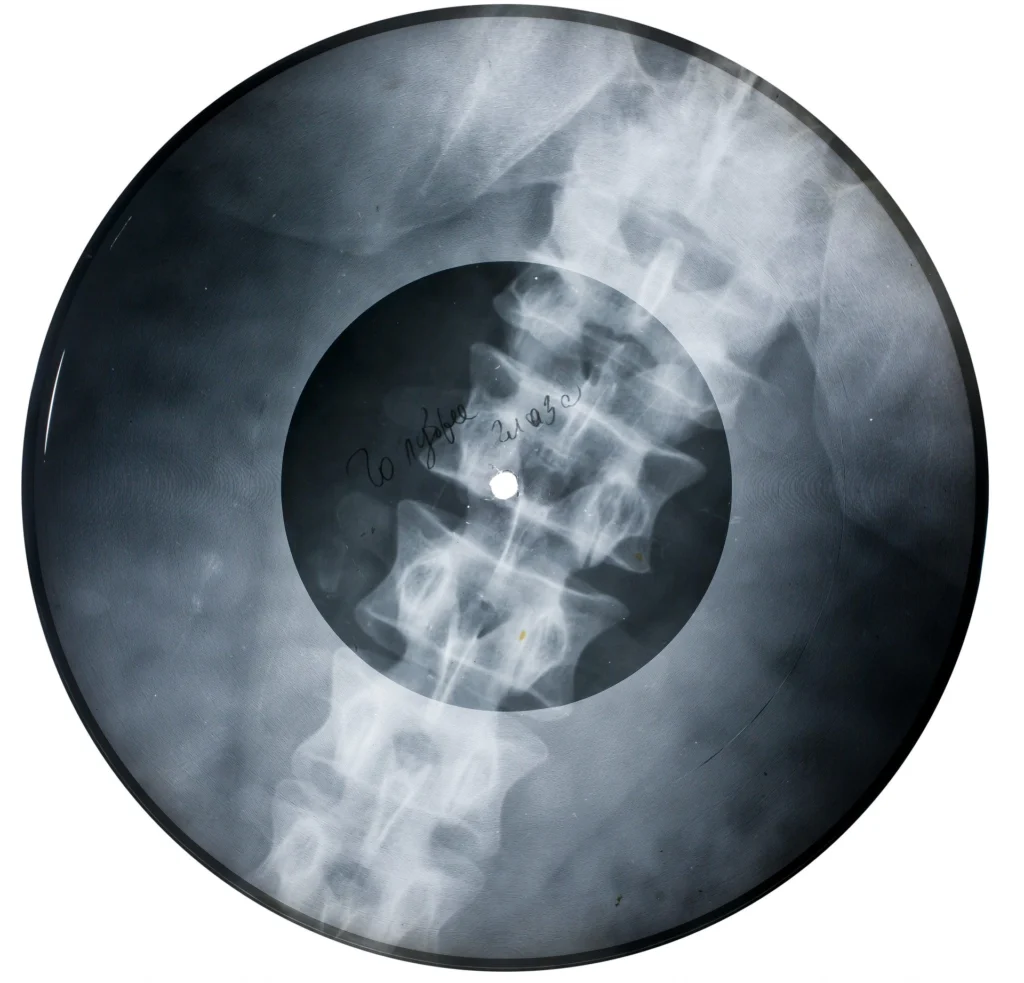

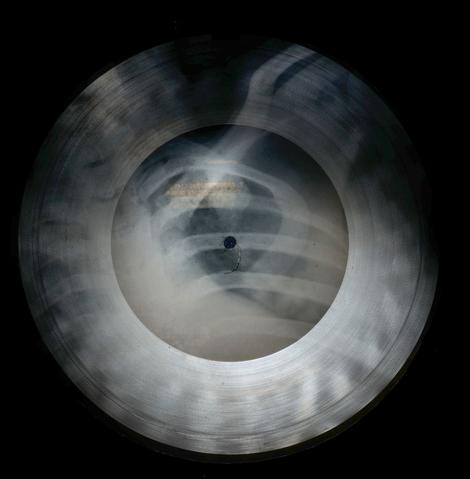

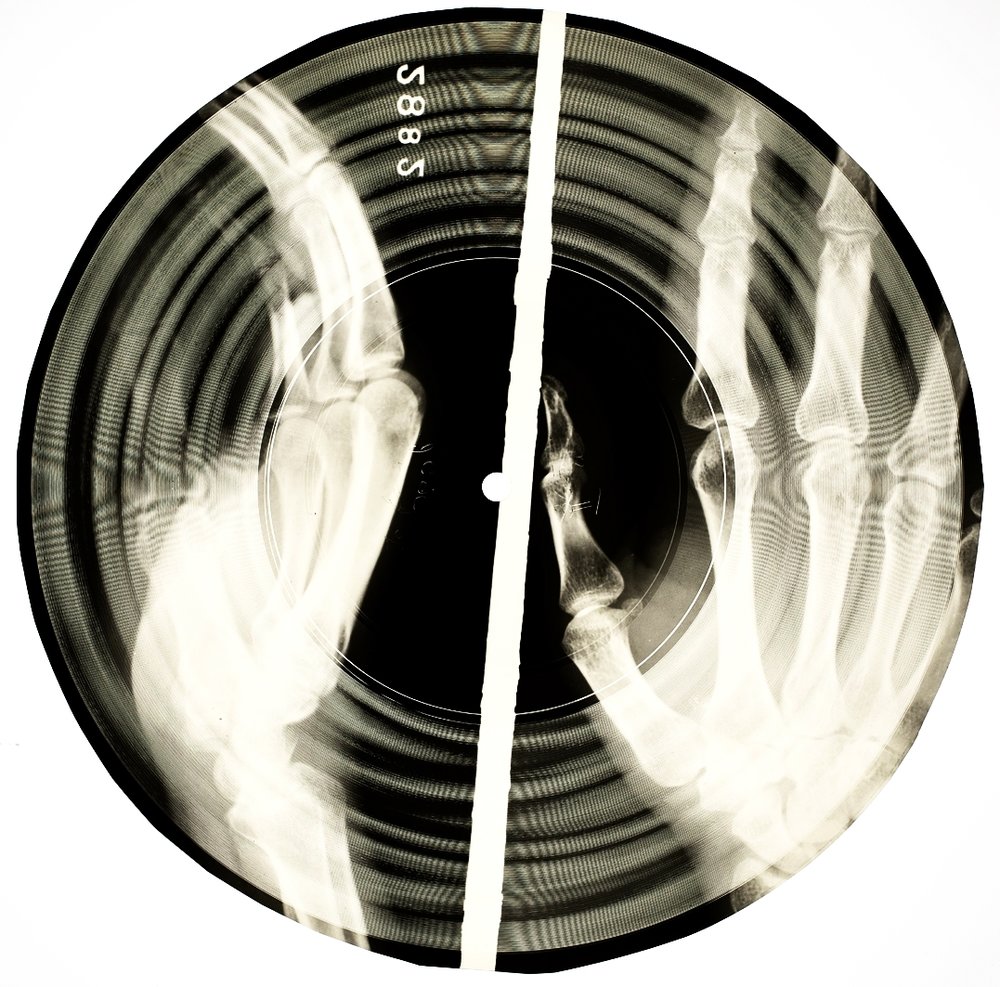

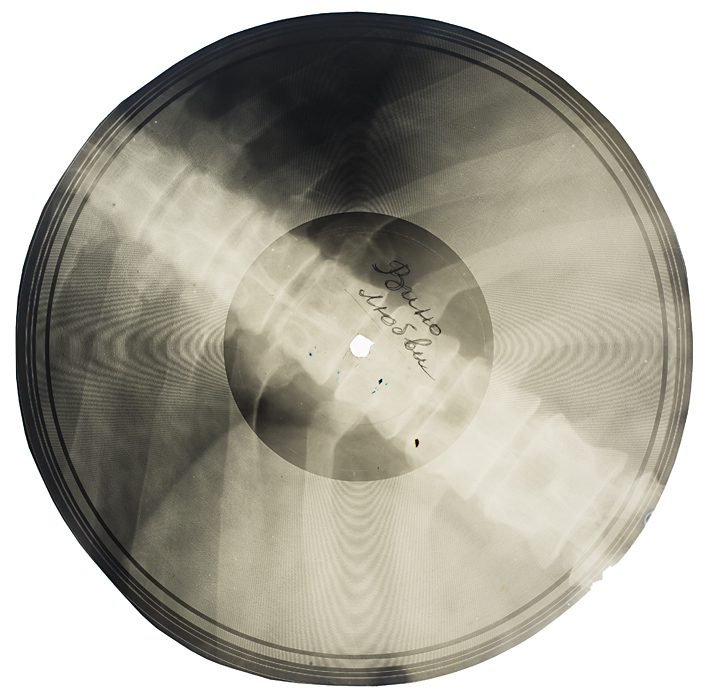

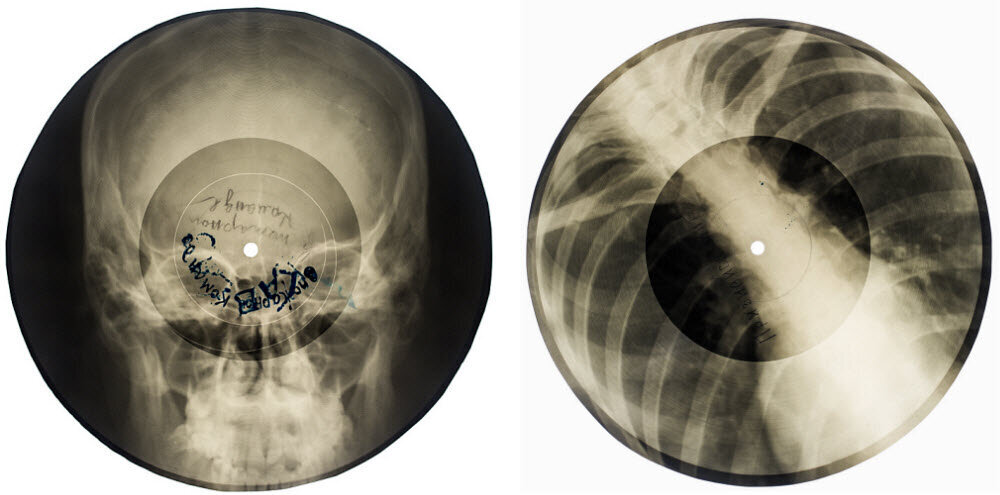

The solution to this scarcity of records and the eventual birth of their substitutes goes all the way back to the beginning of WWII, an era defined by extreme rationing and resource shortages. József Hajdú, an archivist and photographer, came across a curious discovery: X‑ray negatives that weren’t used for medical imaging, but had instead been cut and turned into makeshift audio recordings. It’s now understood that in the late 1930s, disc jockeys of the Hungarian airwaves began repurposing discarded radiographs to create 78 rpm records, as military demands had diverted conventional recording materials away from civilian use. Sound, whether in the form of music or public speeches, was etched onto thick X‑ray film using specialized equipment, which was then cut into roughly 23–25 cm discs (often with jagged edges), labeled, and given a central hole, sometimes just using the lit end of a cigarette.

This improvised method of recording eventually spread beyond Hungary. In Nazi Germany, wartime technical literature circulated among the military outlining how to use a recording lathe to cut records (ostensibly, in case of emergencies) from virtually any flexible, flat surface: aluminum sheets, street signs, plastic, and most effectively, X‑ray film. On the Eastern Front, specifically in Poland, Stanislav Filon, a soldier of the Red Army, encountered this technology, bringing a German-made Telefunken recording lathe to Leningrad (known today as St. Petersburg). With some tweaks, he began duplicating vinyl records onto imitation X‑ray material, laying the groundwork for a distinctly Eastern Bloc form of underground audio culture.

The Audio Letter Underground

In late 1946, Filon opened a modest shop on Nevsky Prospect in Leningrad, today known as St. Petersburg. The sign above the door simply read “Audio Letters,” piquing the curiosity of passersby. Inside, customers discovered a novel service: they could record a personal message onto a small plastic disc and have it mailed anywhere in the Soviet Union.

Of course, the business soon began to sell more than the opportunity to send the 40s equivalent of voice memos. But in order to surreptitiously create pirated music In the postwar Soviet Union, you needed the raw material, and acquiring vinyl blanks was nearly impossible, regardless of demand or financial means. Filon found a creative workaround in Leningrad’s hospitals: used X‑rays.

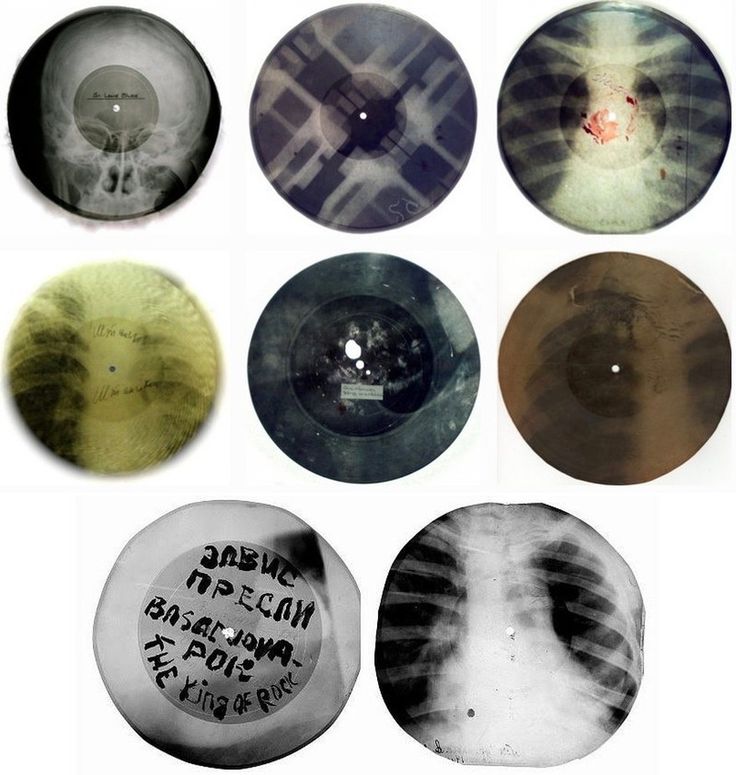

In the Soviet Union, hospitals were required to dispose of X‑rays within a year due to the material used to create them at the time being highly flammable, making them a relatively easy and inexpensive material to obtain. Radiology departments, eager to offload what they considered dangerous waste, gladly handed over stacks of old film to the polite young man who came asking. Soon, Filon was copying Western music onto these radiographs, often bearing ghostly imprints of ribs and skulls, and selling them for five to fifteen rubles each, with custom orders costing more. His studio operated late into the night, producing unauthorized recordings almost as fast as the orders came in.

Golden Dog Rises

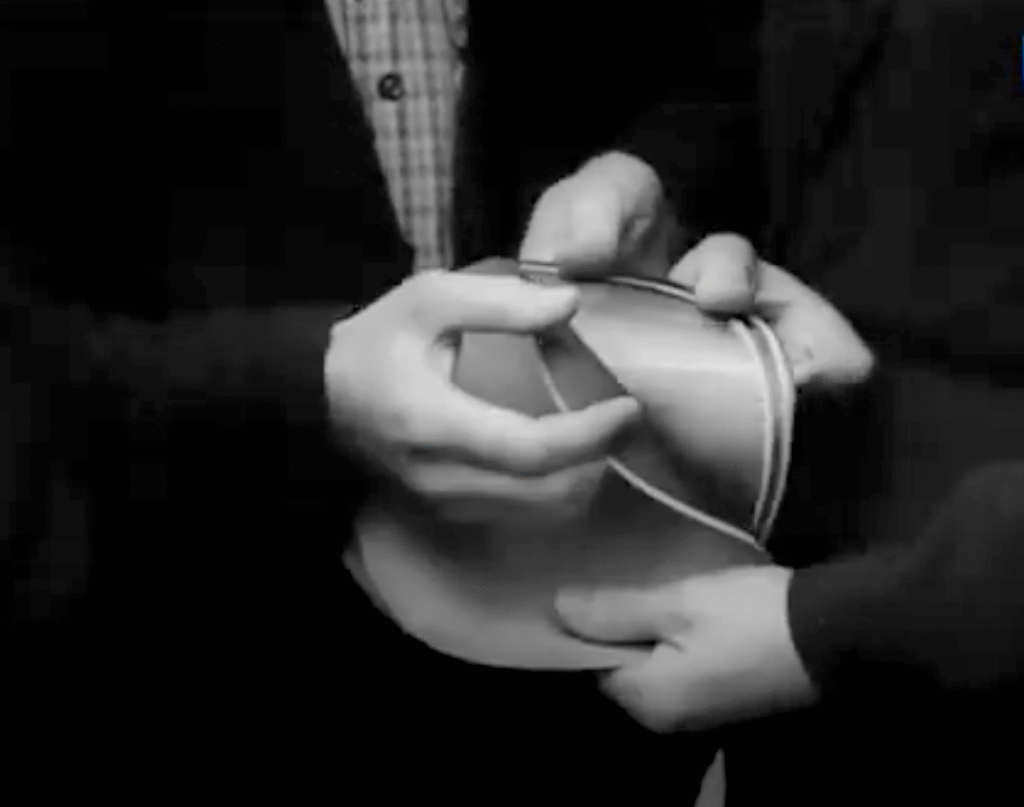

Filon’s success didn’t go unnoticed. In early 1947, two 19-year-olds, Ruslan Bogoslovsky and Boris Taigin, frequented the shop. Fascinated by the music but unable to afford Filon’s “bone records,” they decided to take matters into their own hands. After covertly studying key components of Filon’s machine while standing in his shop, they began building their own version. With materials in short supply, they scoured flea markets and salvaged parts from drills, gramophones, and other discarded devices, eventually assembling a homemade recording lathe. Their impromptu solution marked the beginning of a broader DIY movement in Soviet underground audio culture.

Boris Taigin and Ruslan Bogoslovsky named their newly-formed underground label the Golden Dog Gang, a nod to Nipper, the iconic HMV dog, and even designed a logo for their illicit records to mark them apart from Filon’s shop records. Working in the cellars of Leningrad, this group of dissident music lovers produced handmade recordings in the thousands. The makeshift discs, whether they came from Golden Dog or Filon’s shop, were only good for a small handful of plays each before quickly degraded the fragile material, as the steel needles of the gramophones they were played on would quickly tear up the material. The records were inherently disposable, and if someone truly loved a particular song, he or she would have had to make the extra effort to find another recording, if it was even still available.

Competitors and Consequences

As demand grew, so did the amount of competitor operations. Groups from around the city, as well as Golden Dog, built additional lathes and expanded their clientele throughout the late 1940s. But near the end of 1950, authorities took notice and launched a crackdown operation on every known illegal recording studio in Leningrad. Equipment and materials were seized, while the individuals involved in production were arrested and sent to prison. Taigin lost it all, managing to hide only a single Golden Dog record, a personal one-off piece featuring a photo of a nude woman on the back, in his parents’ apartment, everything else was confiscated.

Bogoslovsky received a three-year prison sentence, Taigin was sentenced to five years, followed by another five in Siberian exile. He later said he was shocked by the crackdown, never believing the authorities would care enough to arrest them. Both men were sent to the gulag and remained imprisoned until Stalin’s death in 1953.

Upon their early release following the death of Stalin, they returned to the work they loved, now crafting more elaborate and carefully designed discs. Bogoslovsky reportedly paid hospital orderlies (now aware of the value of their material) and dug through medical dumpsters to secure discarded X‑ray film. Over the course of two decades, he produced over a million bootleg records, capturing everything from Western pop like The Beach Boys to classical compositions, all on ghostly, translucent images of Soviet anatomy.

Cultural Currency

Whether or not inspired directly by the Golden Dog Gang, the technique of pressing music onto X‑ray film rapidly spread among music-obsessed youth across nearly every major Soviet city. The underground industry behind these records became semi-officially known as roentgenizdat, or roentgen-publishing (in the Russian language, X‑rays are referred to by the name of their discoverer, Wilhelm Roentgen). By now, each record typically cost about as much as a quarter of a bottle of vodka, which meant that even people with a modest income were able to access the recordings for themselves. Soft enough to engrave yet sturdy enough to preserve grooves, X‑rays offered a crude but functional alternative to vinyl.

The music did not just include Western tango, jazz, and rock n’ roll but also music made by overseas Russians (branded “traitors” by the government) and even impromptu recordings by local musicians deemed unfit for mass audiences. Sometimes, radio amateurs got involved and took direct recordings from the international airwaves and pressed them onto the X‑rays. Bone records were sold discreetly on street corners and at flea markets. Dealers loitered in public areas not unlike where soft drugs might be sold today. For those in the know, more private transactions could be arranged in apartments through trusted contacts.

While sound quality was far below that of official pressings, these discs allowed for three minutes or so of forbidden music per side, enough for many to risk it. As recording technology advanced and electric turntables became available, the lifespan of a bone record improved, some could now be played 30 to 40 times. By the late 1950s, millions of these ghostly, translucent records were in circulation, often described as the “common currency of the Soviet bloc.” and just as with samizdat and other DIY-based subcultures in the Soviet Union, an informal ecosystem of sharing and distributing the recordings began to take shape, with music lovers and their trusted friends often gathering to listen to the music in private kitchens (a new innovation, as apartment buildings from the Stalin period and earlier were communal and roommates seldom trusted each other), many of them running record-pressing operations almost anywhere they could operate in peace, from garages in the city to garden sheds in the countryside.

Silencing the Swing

Several structural and cultural shifts helped solidify roentgenizdat as a widespread underground practice. One major factor was the Soviet regime’s escalating crackdown on jazz after WWII. Once a key element of allied unity in the face of the axis powers, official newspapers like Pravda and Izvestiia began publishing articles condemning jazz concerts, echoing the views of Andrei Zhdanov, the architect of post-war cultural policy. The Zhdanov Doctrine denounced anything outside of worker-centric mass songs or folk-inspired socialist compositions as an “ideological diversion,” labeling foreign and lowbrow art forms as subversive threats, sometimes going even further and targeting the country’s most prominent classical composers.

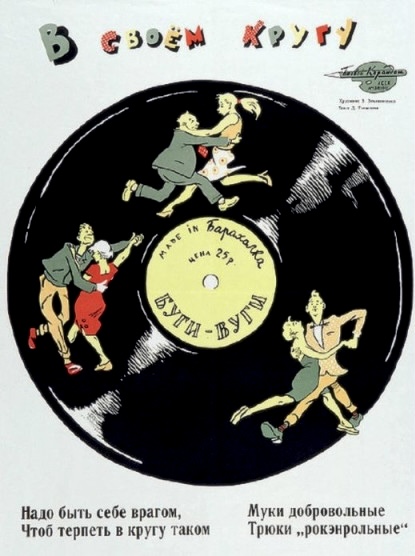

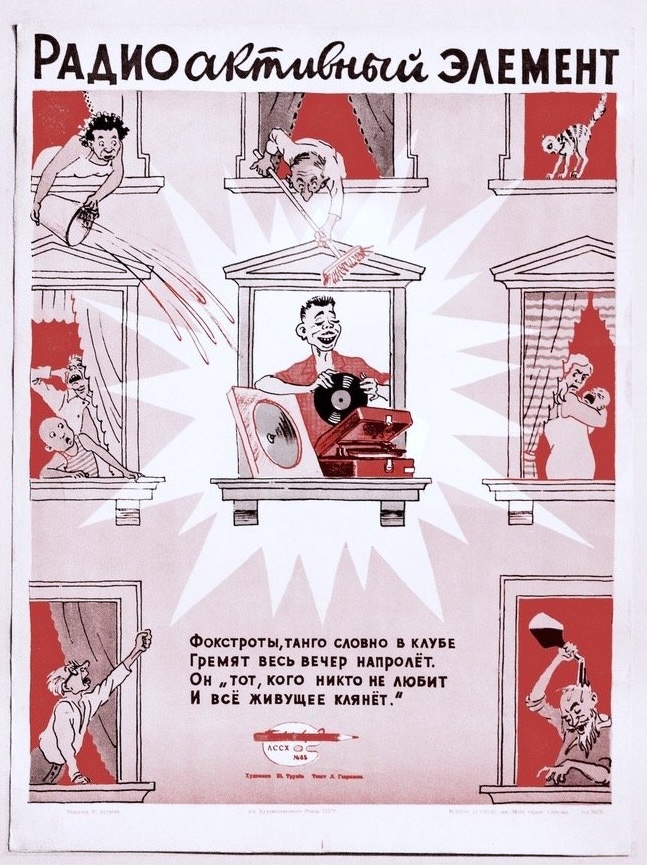

Jazz music, in particular, was seen as a foreign threat to be eradicated. Entire dance styles and rhythms such as swing, foxtrot, and tango were forbidden or strongly discouraged in community dance halls while the musicians that encouraged those dances with there music were scrutinized. Though not all musicians working in the genre were explicitly imprisoned or executed, many faced repression through censorship, surveillance, performance bans, or forced shifts in style and genre to align with the principles of socialist music. By decade’s end, several popular jazz performers such as Alexander Tsfasman and Leonid Utyosov were the targets of anti-jazz campaigns and endured repeated attempts at censorship, while others, such as Eddie Rosner, were given prison sentences.

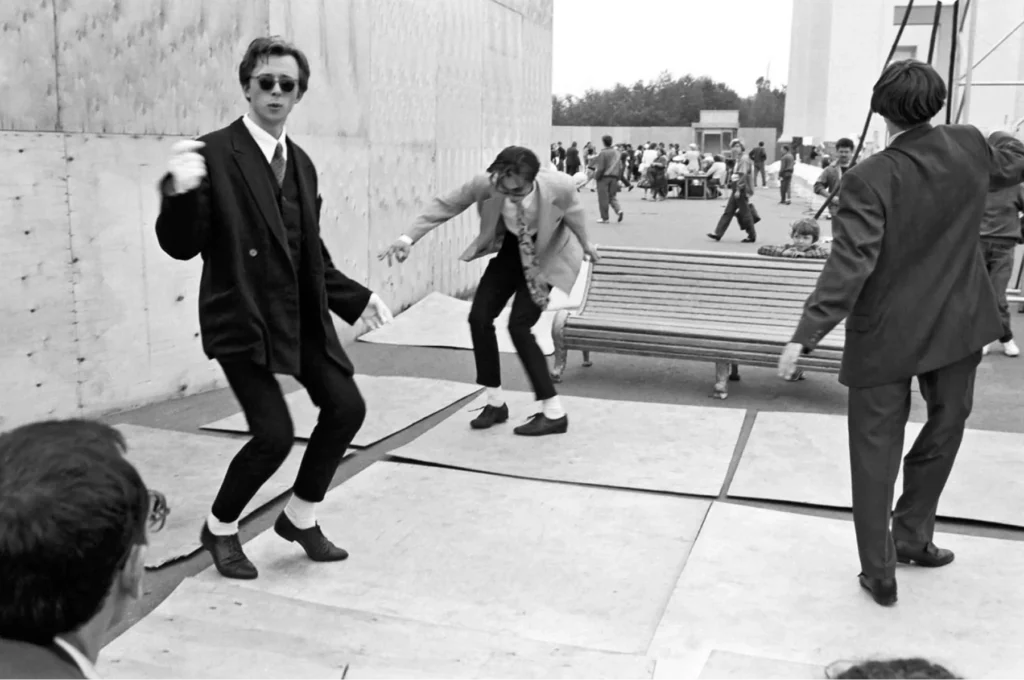

Sharply Dressed Deviancy

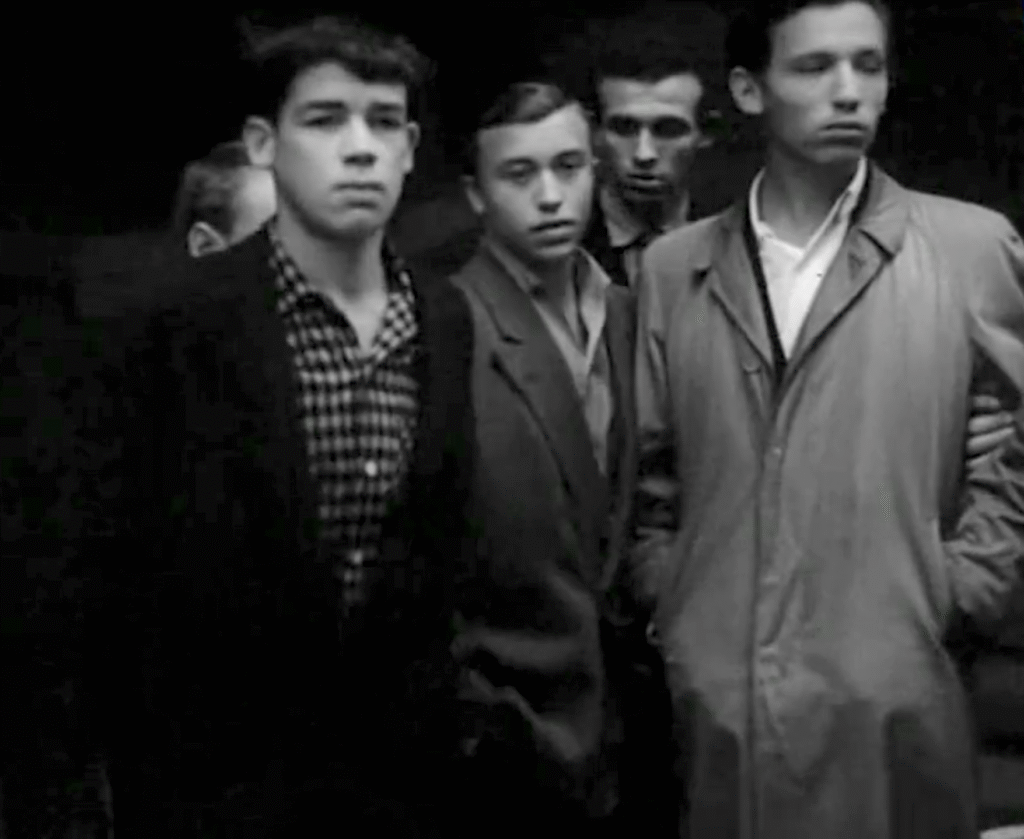

This cultural suppression resulted in the birth of a broader youth counterculture that went beyond dance halls. In 1948, the satirical magazine Krokodil introduced the term stilyagi, best translated as “hipsters”, a pejorative for flamboyantly dressed, Western-influenced Soviet youth. Mocked for their love of jazz, rock, and flashy American-style clothing, stilyagi were portrayed as social deviants. An article from Krokodil in 1949 ridiculed their fashion as a deliberate rejection of “normal people,” while the state newspaper Pravda accused them of being social parasites, street hooligans, and members of the organized crime underworld.

Their style drew from a mix of influences, from 1940s Hollywood musicals like Sun Valley Serenade (one of the few American films to be approved during WWII, instantly becoming a cult hit, seen as a window into Western life) to early rock’n’roll. The style of the time usually included crepe-soled shoes, slicked-back hair, slim trousers, and brightly-colored suits, shirts, or neckties cut from curtain fabric, visually echoing the ethos of England’s Teddy Boys or France’s interwar Zazous. Most of the clothes, if not all, were made by hand or by the stilyagi commissioning back-alley tailors and cobblers willing to go beyond the norm, as official department stores did not sell anything beyond a specific style of standardized (and approved) pieces of mass-produced clothing.

Forbidden Rhythms, Hidden Risks

Naturally, the bone records became an integral part of this underground subculture. The stilyagi prized them not just for the music they carried, but for what they represented: access to another piece of the forbidden culture they idolized. For this reason. they were often the subject of propaganda films and other media, sometimes catching them in the act of trading records and treating it with the same severity as one would an ilict drug deal.

Beyond the regular hit piece in the press, the risk of belonging to this informal scene was always present. Some members would be precluded from education or work opportunities on account of their appearance while others were subject to violence from the state or passersby. On some occasions, it was said that particularly zealous members of the Soviet youth organization, the Komsomol, would patrol the streets, scissors in hand, hoping to forcibly cut the long hair of any stilyaga they came across. One individual, Farafanov, was attacked on a bus for wearing a Western-style coat, his appearance alone enough to provoke violence, owing to the perception being that being able to afford such exotic clothes meant you were involved in some sort of criminal enterprise.

Even merely listening to the underground records came with its fair share of surprises. According to Artemy Troitsky in his book Back in the USSR: The True Story of Rock in Russia, he was aware of an instance in which a bone record listener, eager to listen to his latest purchase, was treated to a few seconds of American music, after which the music abruptly cut, followed by a voice in Russian mocking and insulting the listener for attempting to listen to the latest sounds, then silence. Whether this was a practical joke played by the record dealers or planted by the authorities to scare away listeners was never established.

DIY Behind Bars

But it was not just the fans of Western music that found an interest in roentgenizdat. As many stilyagi and underground music recorders were arrested and sent to the gulag, they came into contact with hardened criminals and an already existing musical subculture. The other side of Soviet music during this period was not what the state approved, but what people longed to create, perform, and hear. Songs that reflected their own lives rather than the official party line.

Within prisons across the Soviet Union, especially the gulags, informal cultures flourished. Dialects were created to allow inmates to speak to each other without being intercepted, literature was being written and passed around, and informal music scenes flourished. These took the form of singer-songwriter (known as authors’ songs) and blatnyak, gritty songs about criminal life. Despite being condemned by the authorities as vulgar, morally corrosive, and counter-revolutionary, the music was incredibly popular, although it was a genre that was disseminated orally, and no recordings existed–yet.

In the tightly controlled Soviet cultural system, you couldn’t simply record or perform music independently. Unless you were accepted into the Union of Composers, you had no legal means of producing music, doubly so if you were incarcerated. And in a state where all art was expected to serve the socialist cause, songs about crime, sex, or street life had no place anywhere. Yet these outlaw ballads, born from native musical traditions, remained wildly popular behind bars and barbed wire. Prisons and gulag camps became self-contained cultural microcosms. Inmates memorized songs and carried them with them upon release, eager to preserve what they had heard.

While Western music, transmitted through X‑ray bootlegs, offered a taste of the outside world, this criminal folklore rooted listeners in a more local, pre-Soviet cultural memory, music tied to lived experience rather than ideological narrative. By the 1950s, roentgenizdat wasn’t just about foreign music; it had become a carrier for suppressed folk traditions. Now, the X‑ray record scene truly was inextricably linked to the criminal underworld, no longer merely a sensational smear tactic in the state press. Having learned about the new possibilities of sharing music, the criminals wanted in on the action.

Straight From the Underground

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the gulag system was dramatically scaled back. Between 1953 and 1960, the inmate population dropped from roughly 2.5 million to 550,000, and a wave of former prisoners re-entered Soviet cities. Their reappearance sparked widespread concern, some of it justified, much of it moral panic, about rising criminality. Bone music became part of that anxiety. One young man, imprisoned in the early 1950s for drunkenly fighting with police, first heard about bone records in the camps.

Upon release, he sought out Bogoslovsky in Leningrad and began working for him, eventually earning enough to commission his own lathe and start bootlegging independently. By then, the trade had become more structured, more commercially-oriented, and more dangerous. It was now not unheard of that armed gangs would ambush black-market deals to steal valuable records to sell elsewhere.

On the other hand, this led to more opportunities for unofficial musicians, who were now able to reach wider audiences. Musicians who existed outside the state system, like Arkady Severny, barred from the Composers’ Union, rose to underground fame by first having recordings of his blatnyak songs shared on X‑ray film. In a few decades’ time, Severny would go on to perform for Brezhnev, a sign of how deeply embedded these sounds had become in Soviet culture.

Others, like Severny’s friend and producer Rudolf Fuchs, lived a far more precarious life. Fuchs sold his own blood to hospitals weekly just to fund his first recording lathe, and spent years cutting forbidden songs onto salvaged X‑rays to be sold in alleyways by street dealers. For him and many others, bootlegging was not just a trade, it was an act of cultural rebellion, and he was one of 20–25 people doing so in a city at any given time. By the early 1960s, the trade became increasingly open, with bootleggers brazenly positioning themselves outside the entrances to official record shops, offering passersby an alternative to state-approved music.

Bone Records for the Cultured and Curious

Beyond nonconformists and criminals, the bone record phenomenon also served listeners who were older, more sophisticated, and interested in culture from other parts of the world beyond the West. Some older listeners of these underground records were keen on listening to the music of their prime years, which often meant the pre-revolutionary era of Tsarist Russia, or just after the revolution. Emigré performers such as Pyotr Leshchenko, banned from entering the Soviet Union either due to exile or because their music, often performed in gypsy or cabaret styles that were popular with the White Russian exiles abroad during the 20s and 30s.

Similarly, bootleg recordings of classical and opera music from foreign countries made their way into the black market. Perhaps even more surprisingly, songs from Bollywood were available, specifically ones from Raj Kapoor’s films, owing to the popularity of Indian cinema in the Soviet Union during a period of cultural exchange and collaboration between the two countries; as a result, many fans wanted to listen to the music from their favorite films at home. There were seemingly as many reasons to seek out bone records as there were people seeking them out.

Western Encounters with Bone Records

For many years, roentgenizdat remained virtually unknown outside of the USSR. One rare exception was Richard Judy, an American exchange student who studied in Moscow from 1958 to 1959. During his stay, he managed to collect 18 X‑ray records, all containing forbidden jazz tracks. At the time, jazz itself was considered subversive by the Soviet regime. His collection, donated only as recently as 2021, became one of the earliest documented Western encounters with this underground medium.

Another indirect witness was possibly even Elvis Presley himself. Rudolf Fuchs was said to have once received a signed photograph of Elvis after convincing a friend in the navy to mail a letter to his fan club while abroad. The latter then invited Fuchs to Graceland in 1977, providing an airline ticket which the Soviet government surprisingly approved, almost a total impossibility at the time. Fuchs recalled being nearly laughed out of the visa building, the officials hardly believing that the real Elvis would write someone such as him. As a result of his trip to Graceland, Fuchs claims to own an engraved gold watch gifted to him by the King himself.

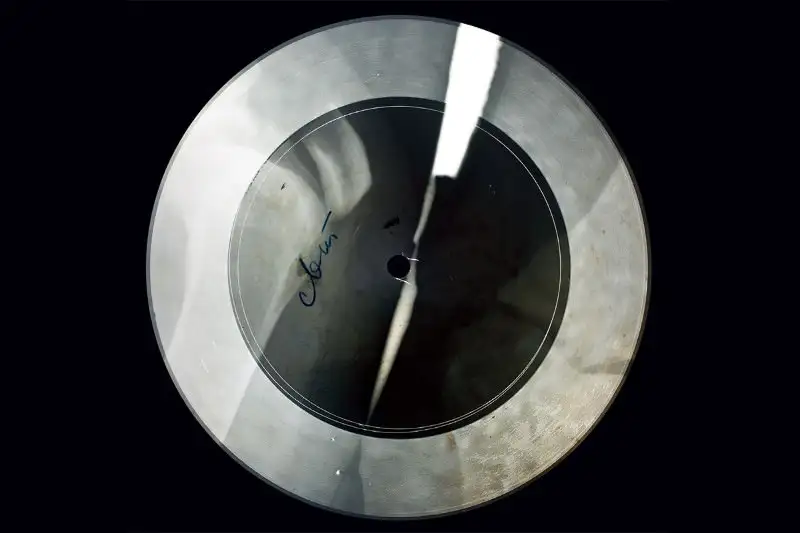

A New Market

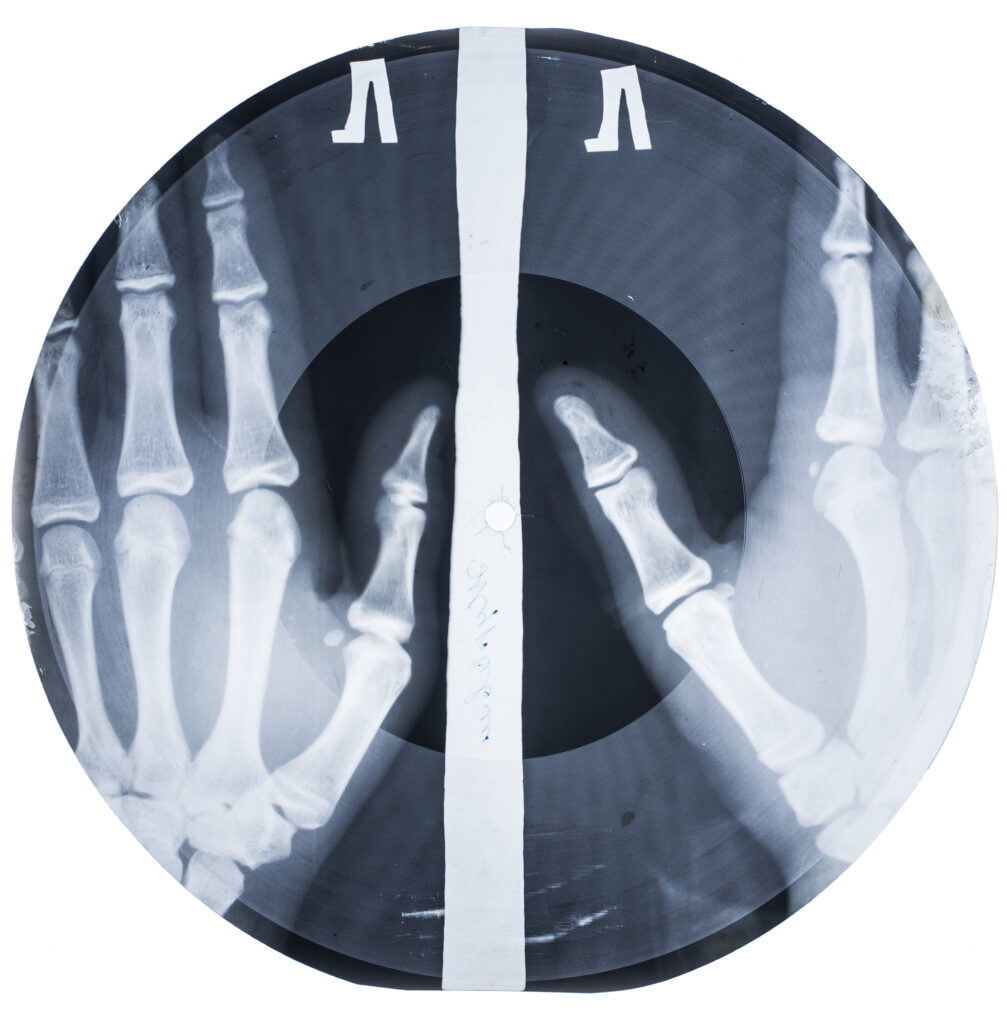

Despite these exchanges, the bone record phenomenon has only been studied extensively for a little over a decade now. “The most common image you’ll find on these records is the rib cage and sternum,” explains Stephen Coates, a British musician and researcher of the bone records. “Older Russians often referred to them as music on the bones or music on the ribs.” The nickname is literal. Many X‑ray records bore ghostly chest scans, a result of mass tuberculosis screenings required across the Soviet Union throughout the 1940s and ’50s and still common in former Soviet countries today.

Stephen Coates, also a writer, producer, and broadcaster trained at the Royal College of Art, stumbled upon this forgotten phenomenon in 2012 while performing in Russia as The Real Tuesday Weld. At a flea market in St. Petersburg, he came across a translucent, skeletal disc that intrigued him. Back in the UK, he placed the single-sided faux-flexi-disc on his turntable and was stunned to hear a lively tune which turned out to be a surprisingly good quality bootleg of Bill Haley’s 1954 hit “Rock Around the Clock”, pressed onto an image of two bony hands.

That surreal experience launched what would become the X‑Ray Audio Project, a years-long mission to uncover and preserve the story of Soviet bootleggers who risked imprisonment to share forbidden music and piece together the history of the trade, as well as collect and preserve any X‑ray records found along the way. The project has since grown into a comprehensive archive encompassing oral histories, exhibitions, live events, two books, and several documentaries.

Preserving the Skeletal Underground

In the process, Coates encountered and recorded the experience and know-how of many of the unspoken heroes of the Soviet Union’s cultural underground, meeting such figures as the late Nikolai Vasin, once known locally in his hometown of St. Petersburg as “the Beatles guy” because of his obsessive interest in the band (a phenomenon we’ve covered elsewhere). Vasin first heard the Beatles on, naturally, a bone record and devoted much of his life to them, even going so far as to claim Lennon faked his death moved to northern Italy in 1980, secretly recording many albums since. When asked if he had heard them himself, he claimed the albums “sounded like John Lennon, albeit with a slight Japanese tinge.”

Beyond his meetings with musicians and the fans who kept their music alive, Coates maintains and works with a network of museum directors, academics, writers, and more who believe in the project. The foremost among these collaborators, Paul Heartfield, is a photographer whose portraiture career spans international musicians and bands to members of the British Houses of Commons and Lords. Beyond just being the man responsible for visually documenting the bone records, Heartfield co-founded The Bureau of Lost Culture with Coates, a wider project aiming to research and share the various unsung countercultural and underground movements of the past, with their findings discussed on a semi-regular podcast.

Together, the two also run Bone Music, a touring exhibition sharing their knowledge of X‑ray records with museums and cultural institutions across the world such as Moscow’s Garage Museum of Contemporary Art and Tokyo’s Ba-tsu Art Gallery.

From Preservation to Performance

In the process, the exhibition has attracted live collaborations and performances from Massive Attack, Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth, Jonsi of Sigur Ros, and even Noam Chomsky. during these live shows, Coates and Heartfield not only tell the tale of this underground audio culture but also demonstrate the lost art, using a period-correct 1950s recording lathe to immediately cut music performed live directly onto X‑ray film, playing the performance the audience just heard back to them to demonstrate the medium’s fidelity.

Many of the recordings that made their way into the project’s archive have been digitized and can be listened to online, including a haunting rendition of Elvis Presley’s Heartbreak Hotel. Other selections include a recording of the Italian opera song “Tre Giorni Son Che Nina”, an anonymous criminal song about breaking into a safe, a Hindi-Urdu song from the 1951 Bollywood hit Awaara, as well as a classic by Ella Fitzgerald, but with sound quality degraded and warped, almost venturing into the territory of a sinister-sounding remix.

How Tape Killed the X‑Ray Star

The era of bone records almost officially drew to a close in 1964 with the establishment of the state-run record label Melodiya, which united all of the Soviet Union’s disparate vinyl factories and centralized the approval and production process of music even further. On the other hand, the government, now realizing it was in direct competition with a burgeoning underground music culture sought to get in on the action rather than make futile attempts to stamp it out.

To that end, the government began mass-producing reel-to-reel tape recorders, selling tens of millions of them over the next several decades. While it’s said that there are occasional bone records of later bands such as Nico and the Velvet Underground floating around, the ability of reel-to-reel to quickly and cheaply copy music in relatively dependable fidelity on one’s own meant that bone records (and their dealers) were now all but obsolete.

The New Sound of Dissent

Thus, Roentgenizdat gave way to Magnitizdat, and a new underground recording culture took the helm. And although there were often still penalties for owning unsanctioned recordings, the censorship was relaxed and the government instead sought to study what was popular and create what they believed would be socialist-friendly analogues to the current trends. The tape music culture also took the careers of various songwriters even further than even bone records could, as their music reached even newer heights, establishing musicians like Bulat Okudzhava, Vladimir Vysotsky, and Arkady Severny as household names and earning them oft-unspoken approval by the authorities, if not opportunities to officially perform their music outright.

By the 1970s, the Melodiya label began releasing jazz recordings as well as what they called Vocal-Instrumental Ensembles, a sort of pop or soft rock heavily influenced by psychedelic aesthetics and funk from abroad. This willingness to open up to new genres of music led to the creation of genres which are wholly unique to the Soviet experience, a sound tradition which persists even today, and is even being revived by some bands such as SOYUZ from Belarus. While Western media was already available to some degree among the other Eastern Bloc countries, by the mid-80s, the situation had changed so far to the point that Western music was available in stores in the Soviet Union proper, with very minor controls compared to the past. The first ever officially-sanctioned vinyl of The Beatles was released by Melodiya in 1986.

Bone Music’s Modern Afterlife

Today, the tradition of bone records is enjoying a similar revival, with Coates’ and Heartfield’s project going on for over a decade now and continuing to reach new audiences. Similarly, a Los Angeles-based record label, Blank City Records, has taken to pressing their own releases onto limited-edition vintage X‑rays, reinterpreting the spirit of bootlegging in a contemporary context.

In the era where practically any song is available to stream instantly, the idea that something so harmless and accessible was once very dangerous to own or seek can serve as a moment to reassess many of the things we take for granted, and while music isn’t a necessity in the strictest sense of the word, the idea that some individuals risked their freedom and sometimes even lives to get a chance to listen to the sounds of other cultures and share them with others is a point that many can admire. As one former bootlegger sentenced to prison remarked to Coates, “We didn’t do it for money. We did it for the adventure. We did it to get the music out to the people.”

Really intriguing. It was so cool, you know, using X‑Ray films for music as well as so sad that they didn’t have proper access to even music that time. We take music for granted, it is such a privilege.