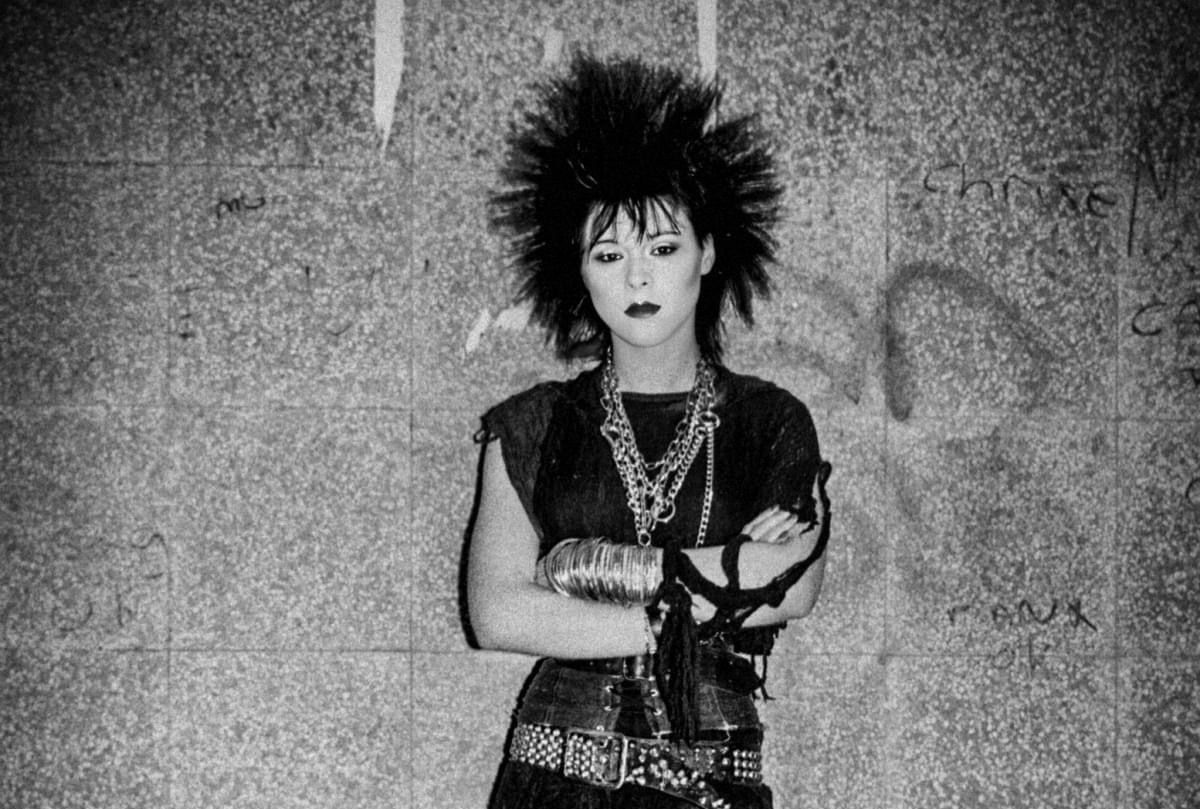

Beginning the 80s, Japanese photographer Shoichi Aoki has quietly built one of the most revealing visual records of London street style, capturing the city’s ravers, goths, artists, and club kids at a moment when fashion was still local, handmade, and deeply tied to subculture. Published in Japan’s Street Magazine, these photographs offered an unfiltered view of how youth identity was being constructed on London’s sidewalks long before social media.

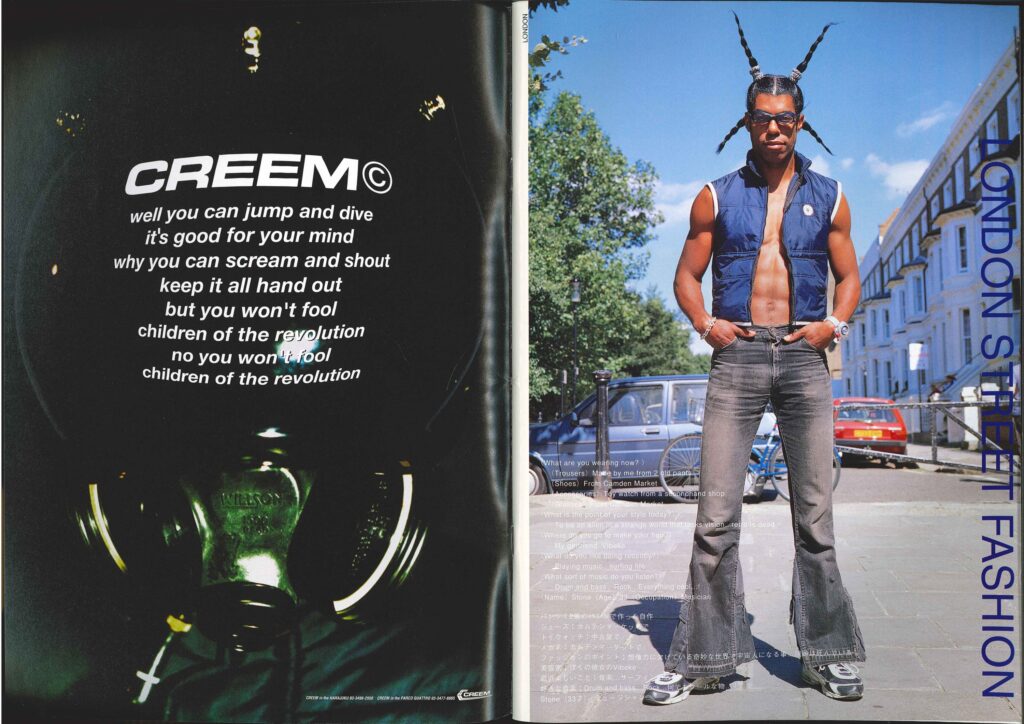

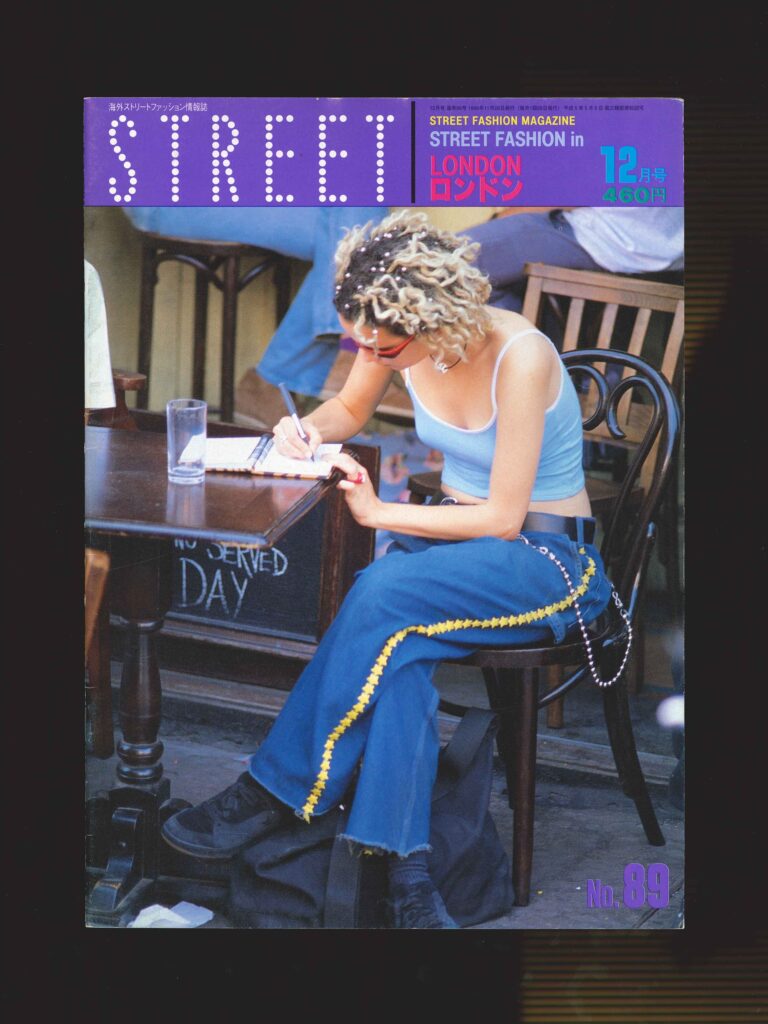

A decade before the internet made fashion globally accessible, the way most discovered what people in other cities around the world were wearing was to purchase fashion magazines such as Street. Founded in 1985 by Japanese photographer Shoichi Aoki, the magazine became a crucial window for Tokyo’s fashion-conscious crowds to view their equivalents abroad.

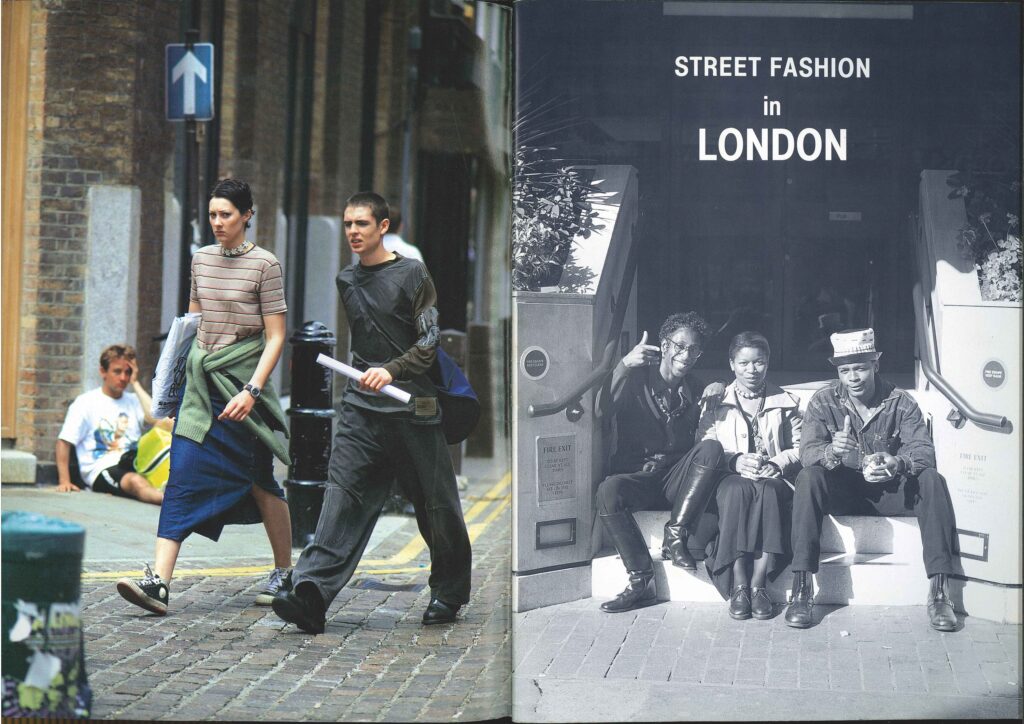

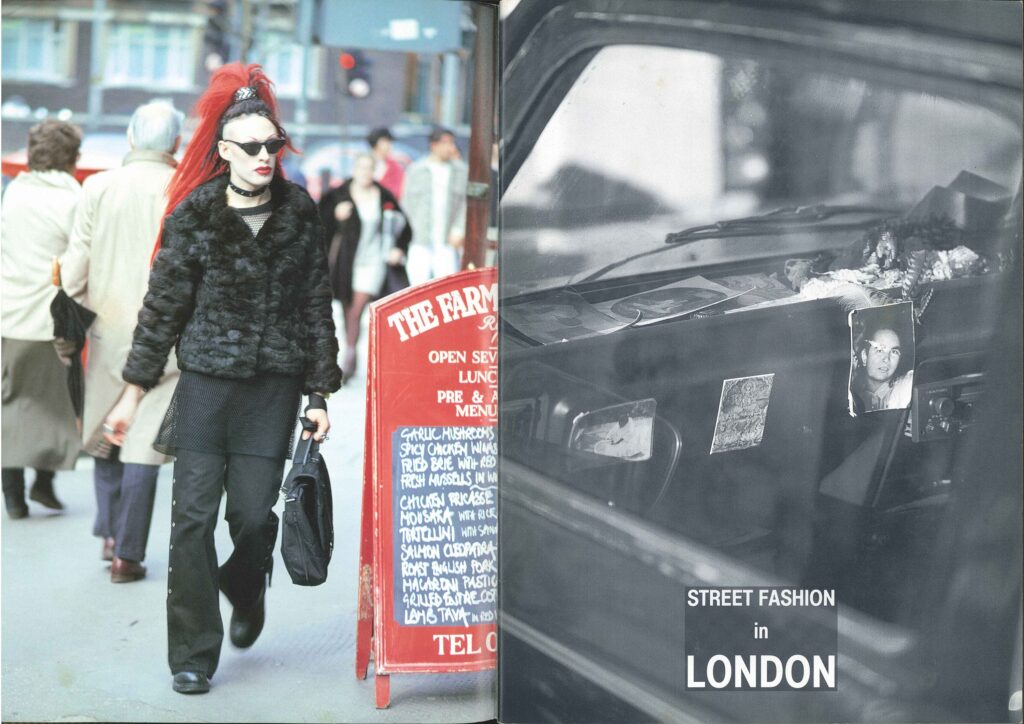

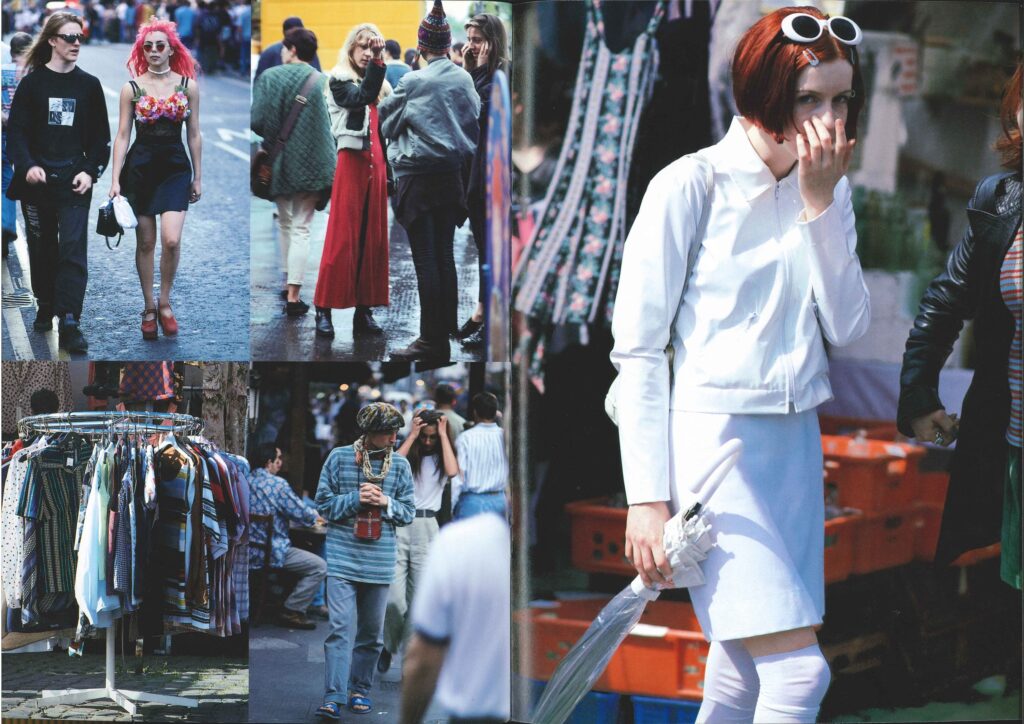

Since then, Aoki has traveled regularly to the UK, US, and Europe, particularly staying in London, photographing interesting people on the street in Soho, Camden, and around the city, with no certain regard for age or background, presenting their outfits with the same direct, documentary approach he used when he got his start documenting fashion in Tokyo’s Harajuku district. Rather than treating London fashion as something dictated by designers or runways, Street Magazine framed it as a living, self-authored culture, allowing younger Japanese readers to see how personal identity was being constructed in real time on another continent, a direct precursor to the way personal fashion is globally presented and shared on social media today.

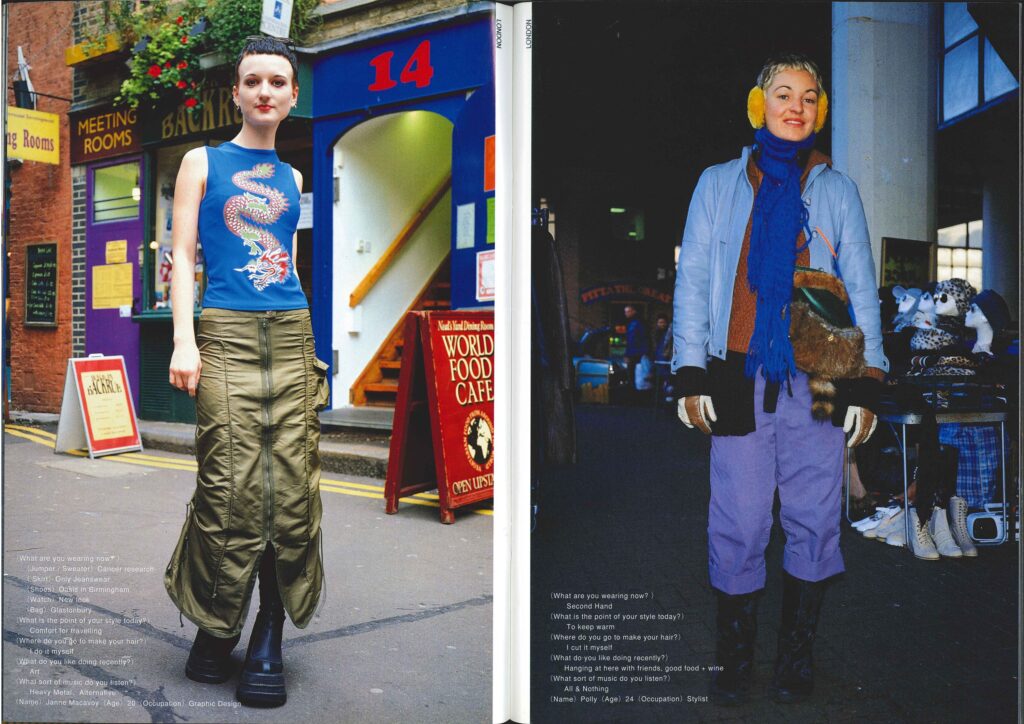

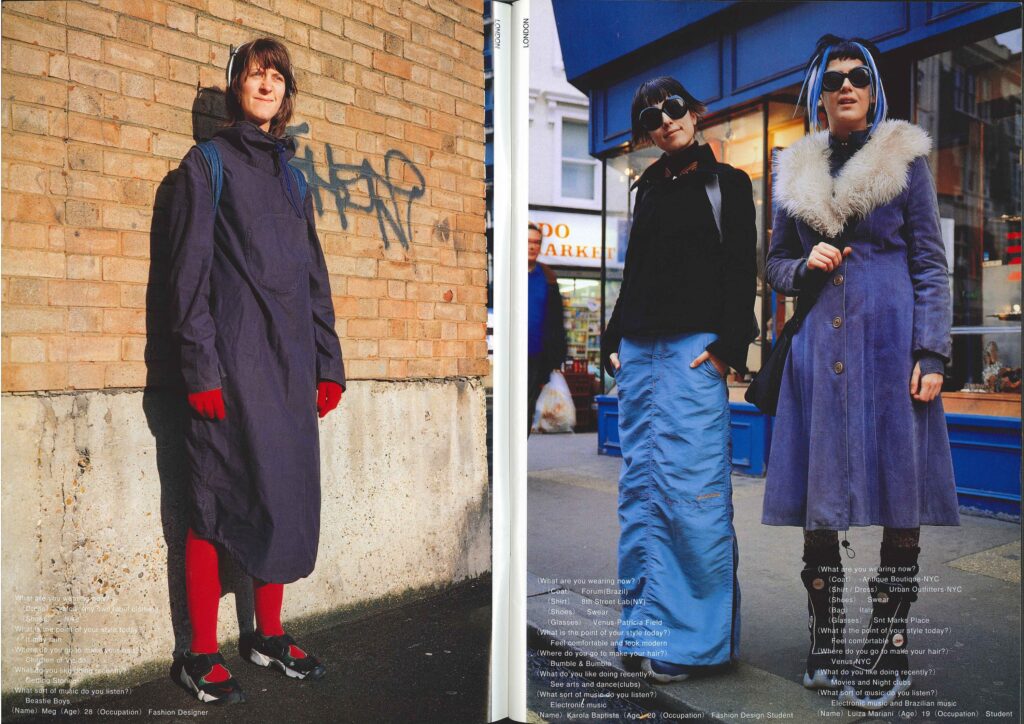

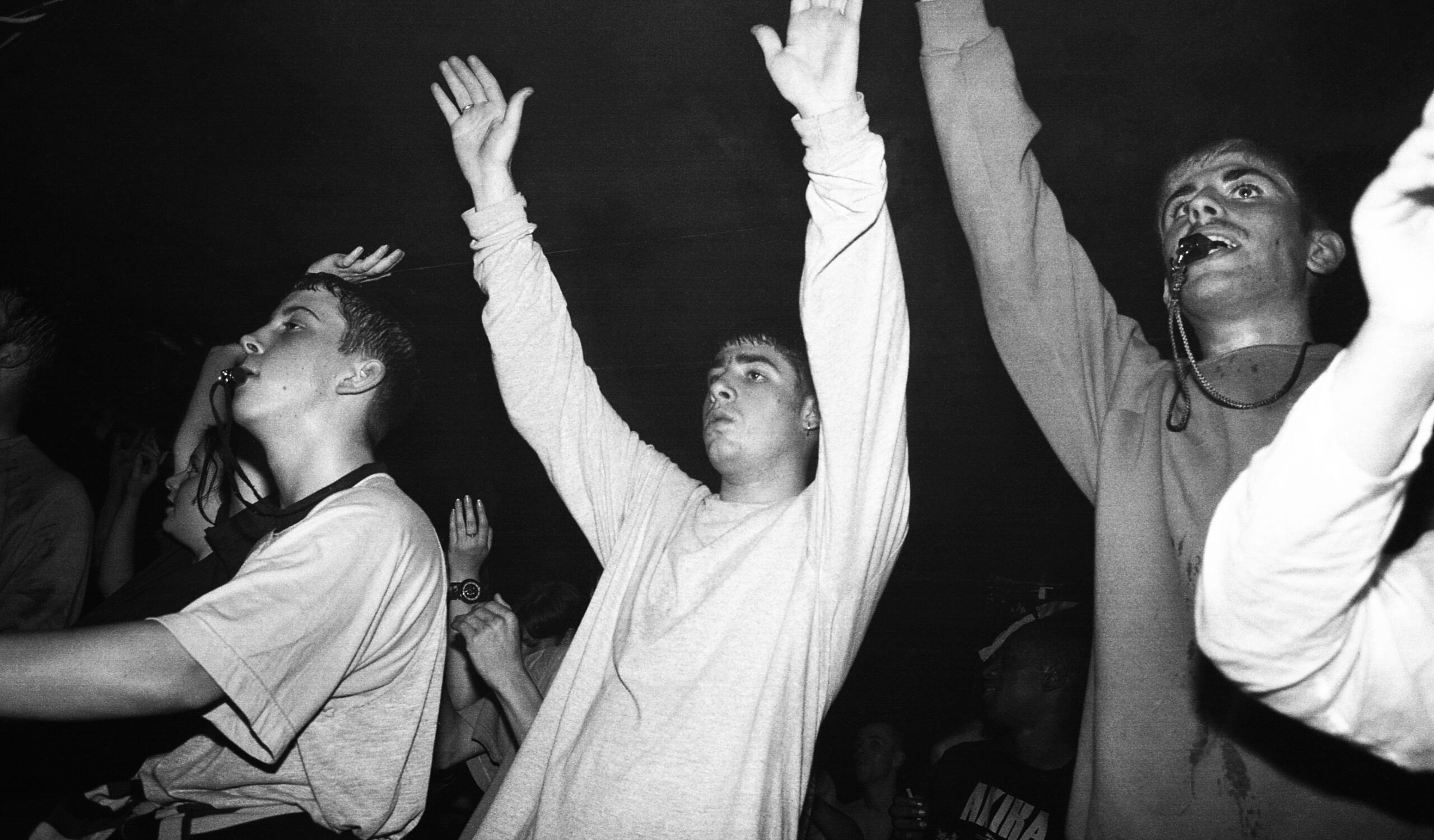

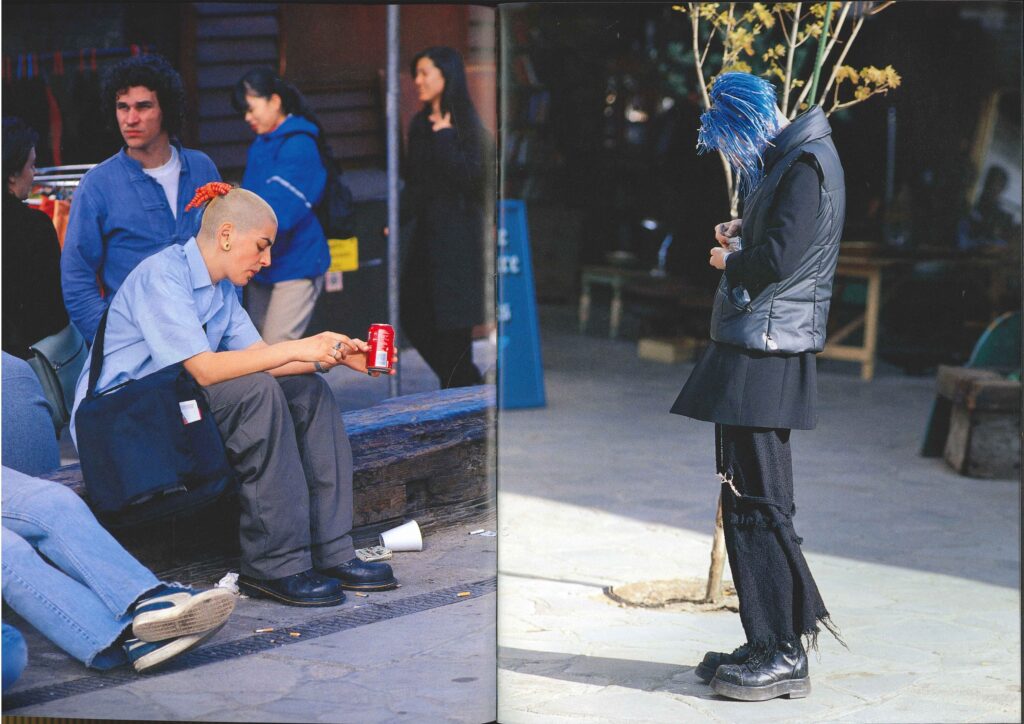

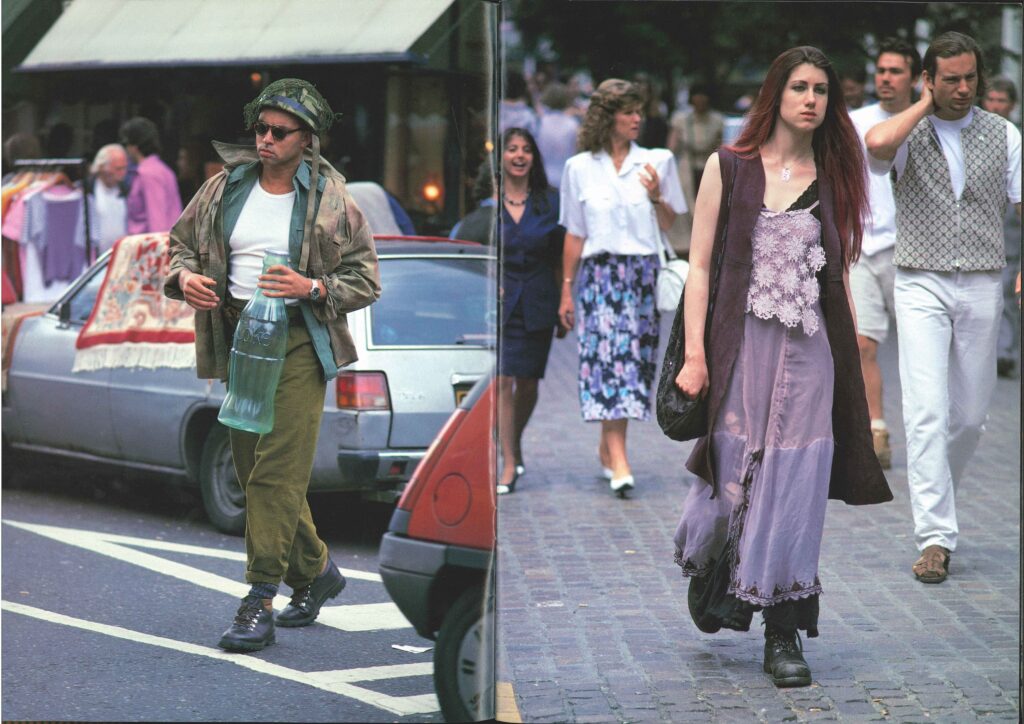

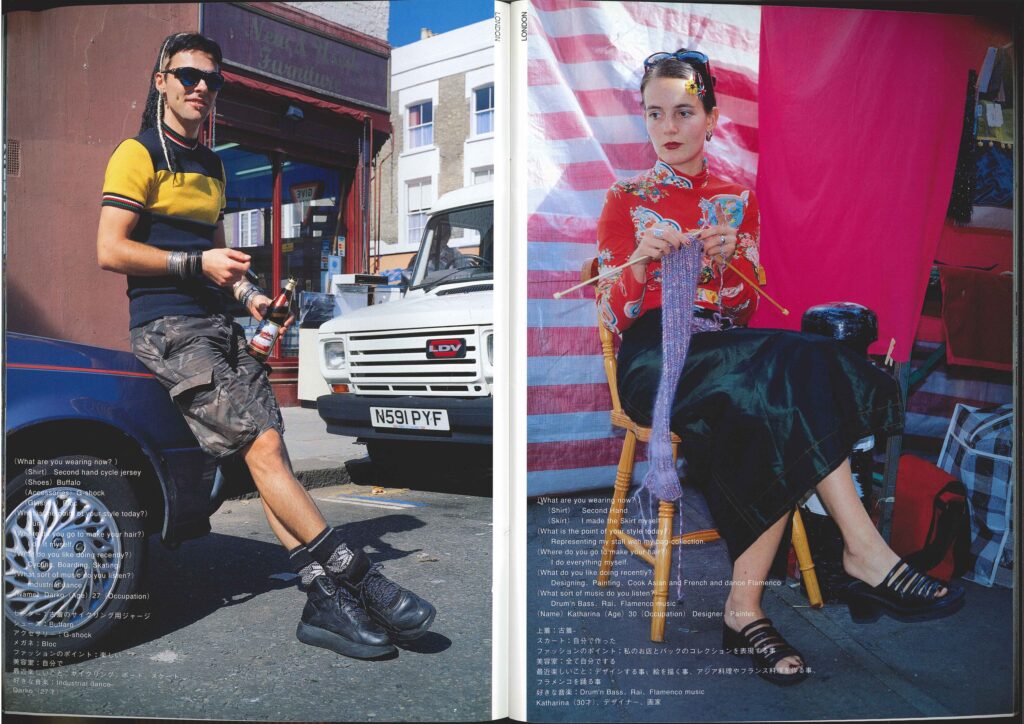

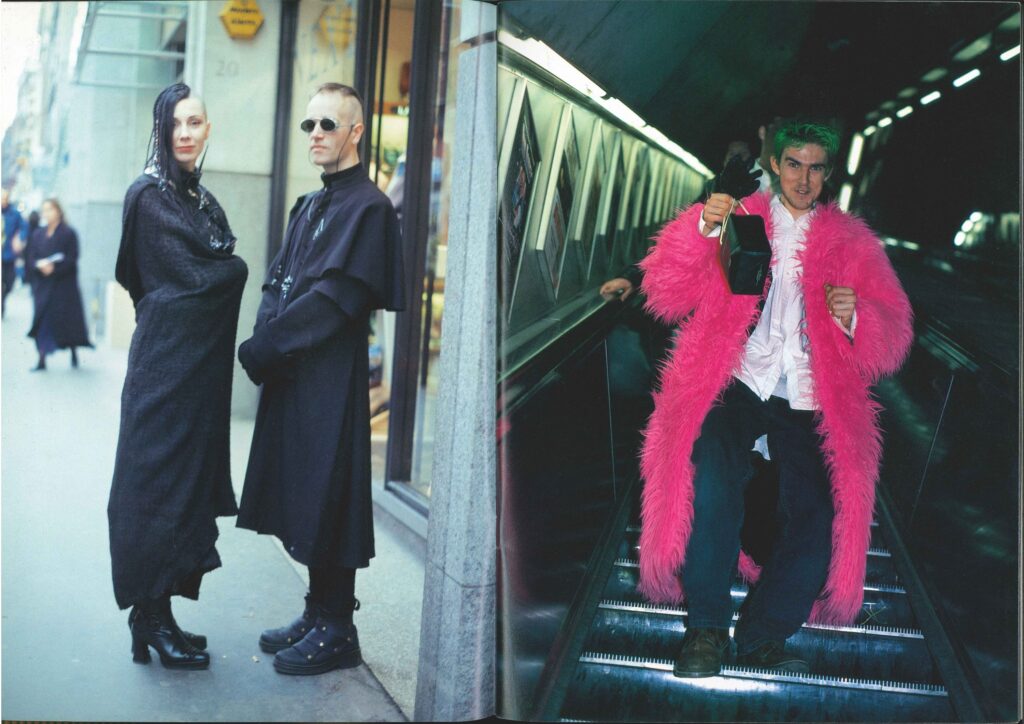

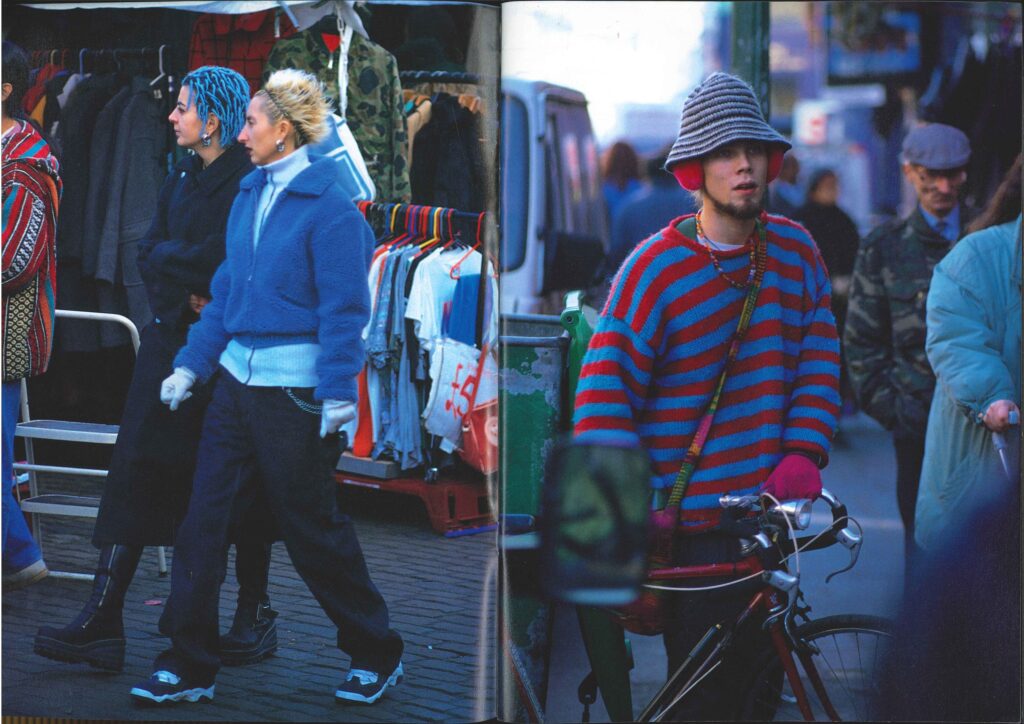

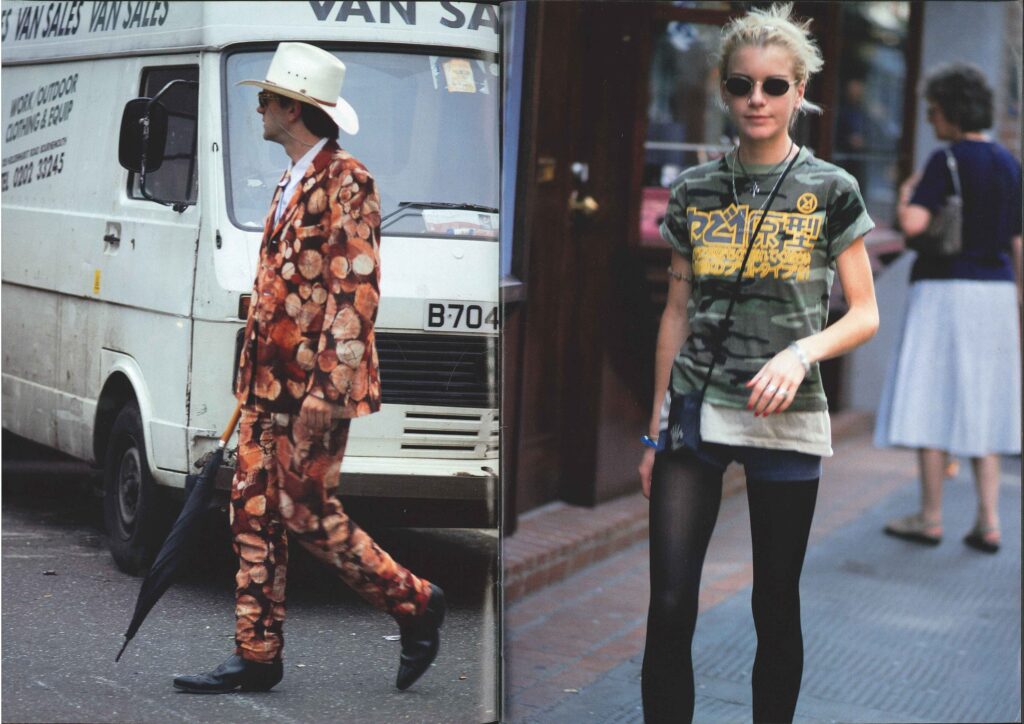

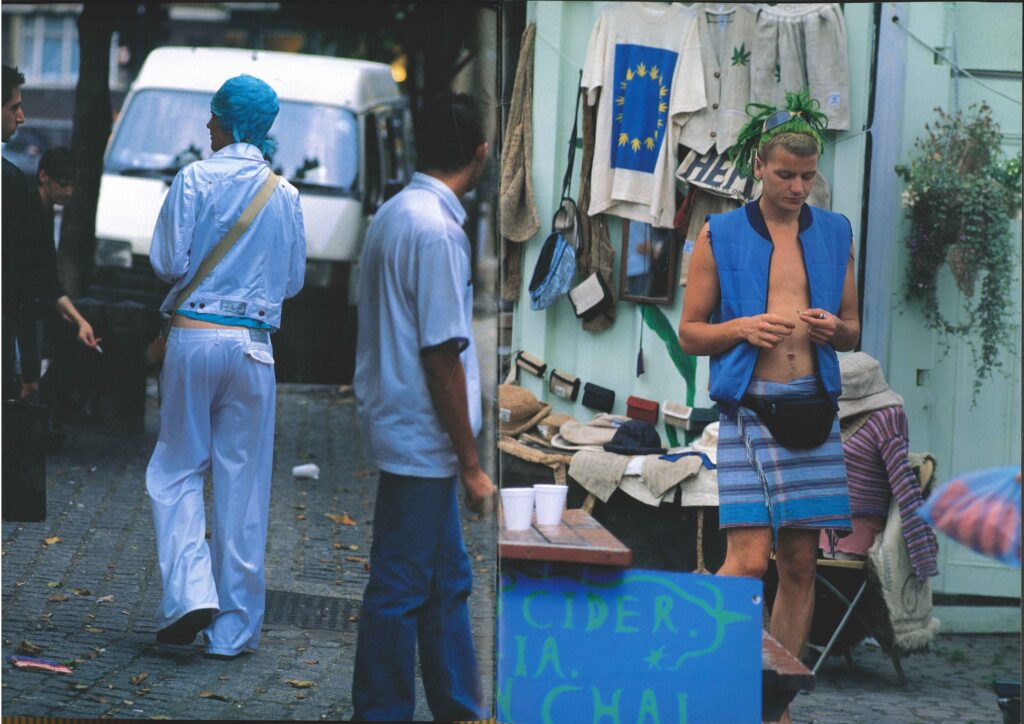

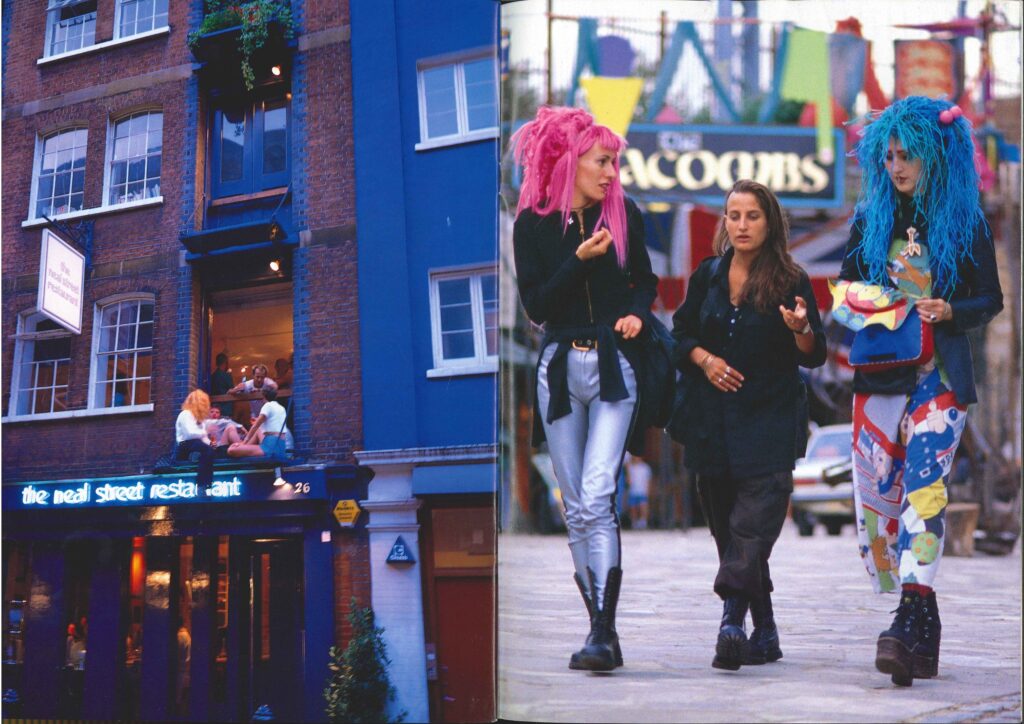

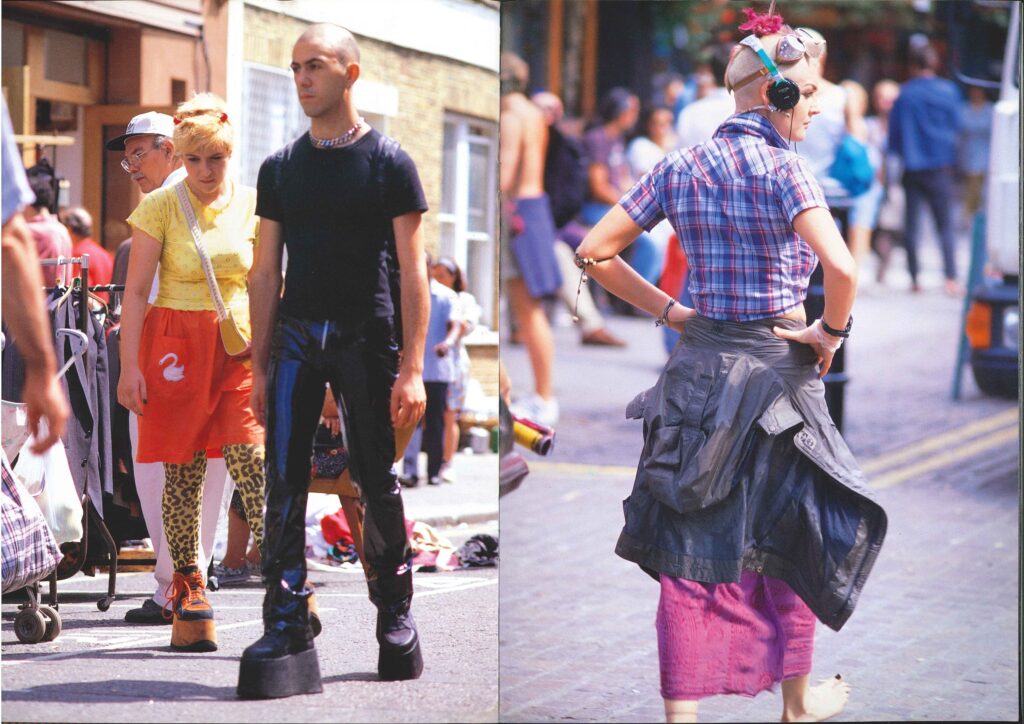

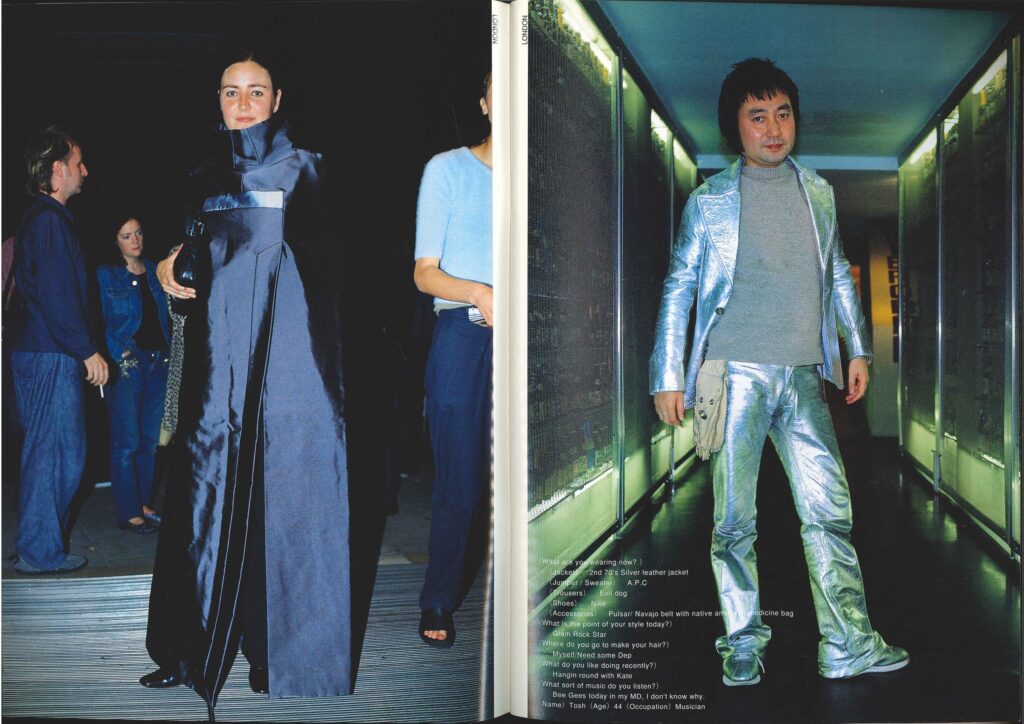

These photographs, shot and published in Street between 1993 and 2000, show the styles of the time, at once slightly legible to us and different in ways lost to the ebb and flow of trends, offering a more authentic view of the era than the nostalgically curated version usually seen when current trends reference the decade. In these portraits you can see styles we now call cyber Y2K, whimsigoth, and raver as they actually existed during their peak.

What makes Aoki’s London work especially compelling is that it captures a city in cultural flux. The mid-to-late 1990s were a moment when British youth culture was splintering and quickly evolving: Britpop was giving way to darker post-rave aesthetics, Camden was becoming a crossroads of cybergoth and neo-hippie styles, and Soho remained a magnet for club kids, fashion and art students, musicians, and outsiders. Aoki photographed all of it without hierarchy. A student in oversized polyester pants, a goth in metallic makeup, or a raver in oversized dyed dreadlocks were given the same neutral framing: full-length, centered, and usually unposed. This was not editorial fashion photography but visual anthropology, a method that made Street feel closer to a sociological record than a glossy magazine.

Aoki’s approach was deceptively simple. He worked with a straightforward 35mm camera, natural light, and a consistent street-level vantage point. There was no styling, no retouching, and no attempt to smooth over awkwardness, sometimes even fully blurry photos were published, or photos that didn’t even feature people at all, sometimes Aoki opted to shoot a scarerow in rags on the side of the street or old teapots on display at a boot sale. The result was an archive of culture and clothes as they were actually worn: orange or pink-dyed hair, reflective fabrics, wrinkled vinyl, messenger bags, brightly contrasting color clothes, and DIY modifications that rarely survive in the mind of the mass consciousness when it comes to looking back at the decade. This is one of the reasons Aoki’s London photographs have become so valuable today. They preserve not just trends, but the texture of everyday experimentation, and the last holdouts of regional culture, before algorithms made everything available to everyone, for better or worse.

In Japan, Street Magazine had already established itself as a cult publication by the early 1990s. It was one of the first magazines anywhere in the world to treat ordinary people on the street as legitimate fashion subjects. Aoki’s original Harajuku coverage helped launch the idea that subcultures, rather than designers, were driving fashion forward. When he applied this same lens to London, it created a veritable cross-cultural feedback loop: British youth could unknowingly influence Japanese style, while Japanese readers were seeing a parallel underground evolve thousands of miles away. In this sense, Aoki’s work anticipated the globalized fashion ecosystem of Instagram, Tumblr, and TikTok by decades.

The London images also reveal how much of what feels “current” in fashion is actually recycled from that period. Cyber-inspired eyewear, tribal tattoos, chaotic charity-shop layering, platform boots, mesh tops, and rave silhouettes that dominate contemporary trend cycles all appear in Aoki’s 1990s photographs in their original, less familiar forms. What is striking is how unbranded these looks often were. Before the advent of streetwear, logos were secondary to silhouette, color, and personal styling, reinforcing the idea that identity was the real engine of street fashion.

Beyond Street, Shoichi Aoki is perhaps best known internationally for FRUiTS, the magazine he launched in 1997, which focused almost exclusively on Harajuku style. FRUiTS became a global phenomenon, shaping how the world understood Japanese youth culture and inspiring designers, stylists, and photographers across Europe and the United States. Yet the London work in Street shows another side of Aoki’s career: a roving documentarian of global subculture, quietly assembling one of the most important youth culture archives of the late twentieth century, often compared to the continent-hopping work of Joji Hashiguchi, another Tokyo photographer.

Aoki has often said that he does not judge what he photographs, he simply records it. That philosophy is what gives his London street photography its lasting power. These images are not trying to flatter, sell, or mythologize their subjects. They let people exist as they were, in a moment when style was still largely built offline, through clubs, record shops, flea markets, and scenes that were local before they were global.

Today, as fashion cycles accelerate and the internet collapses geographic boundaries, Aoki’s London photographs from 1993 to 2000 feel almost radical in their slowness and specificity. They show a time when discovering how people dressed in another city required curiosity, physical travel, and a printed magazine passed from hand to hand. In preserving that world, Shoichi Aoki did more than document street fashion, capturing the last era before style became global.

Four decades on, Aoki’s magazines continue to exist today, albeit with a much more irregular output, its niche long having been filled by instagram and other social media feeds, although this is not to say Aoki’s photography has slowed down by any means, as he has taken to the same platform to present his work directly to its fans. However, those curious to study the styles of old and become inspired by the people of that only country which cannot be traveled to, the past, may do so by finding surviving old print copies for sale, or by purchasing digitally scanned compilations of the magazines from Aoki himself at his website.