The version of romanticism truly unique to the 21st century experience may have already come from a lesser-known Swedish artist whose paintings of virtual worlds explored beyond the boundaries of intended gameplay, namely the maps of Valve’s original Counter Strike, echoing a childlike wonder and desire for exploration even beyond the constraints of virtual space.

Many people who’ve played video games for the first time early in their lives often share a common experience of desiring to break out of the game’s intended linear path or play area. Sometimes it’s a half-closed door, never programmed to be opened by the player yet revealing another area of the world, other times it’s a landscape separated from the player by a chain-link fence or window, just visible enough to suggest it exists, but not reachable through traditional means.

To younger players unfamiliar with how video games are constructed, it may as well be an invitation to access a whole new part of the virtual world, and thus access more game to play, if only the boundary could be overcome. In certain cases, you might simply accidentally glitch out of bounds, with no intention of leaving the game area, and find yourself in those same places. In any case, your first encounter with a surreal, half-materialized world is a surreal experience, the sense you have reached some limbo state and the realization there is truly no world beyond the game. As adults, we’re aware of this reality, yet many still try to break out of bounds on purpose, either to see how the game and its moving parts were made or even to get through a speedrun, all the while retaining some sense of exploring the unknown, even from the comfort of being behind a screen.

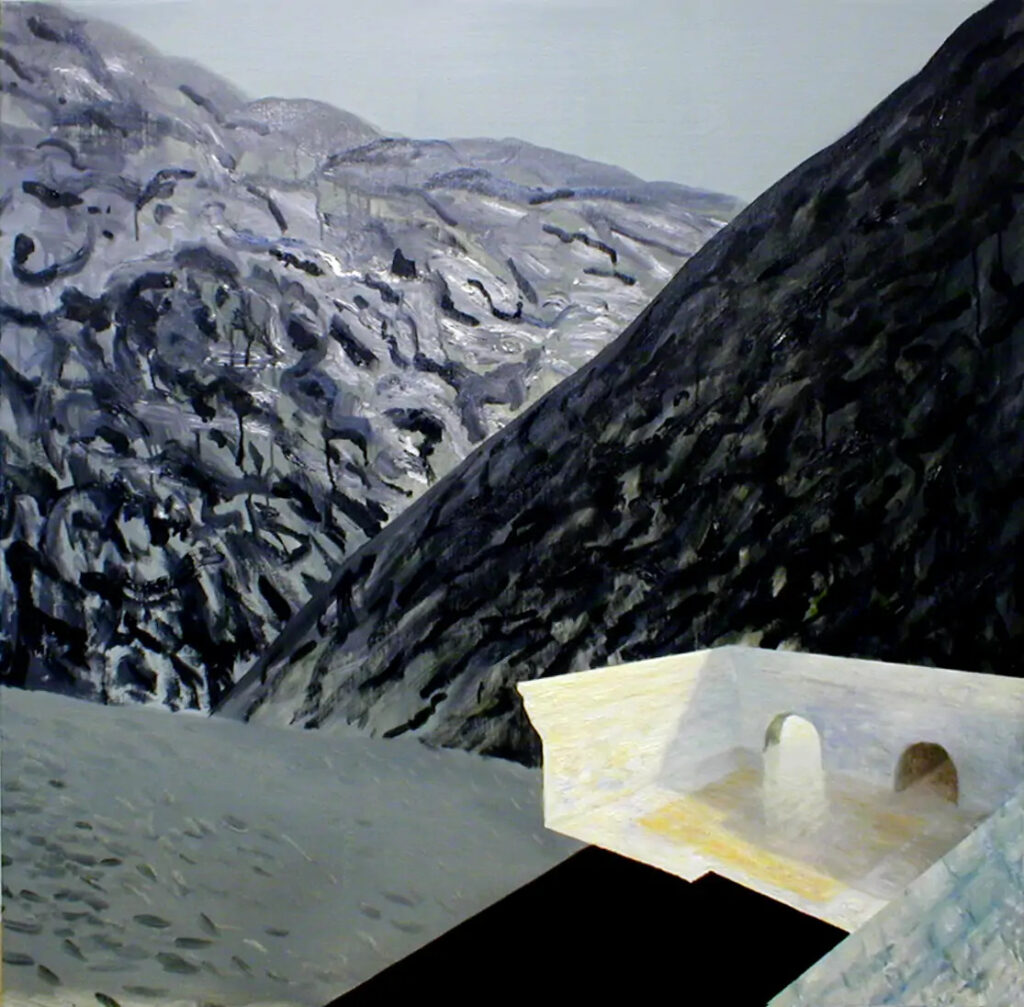

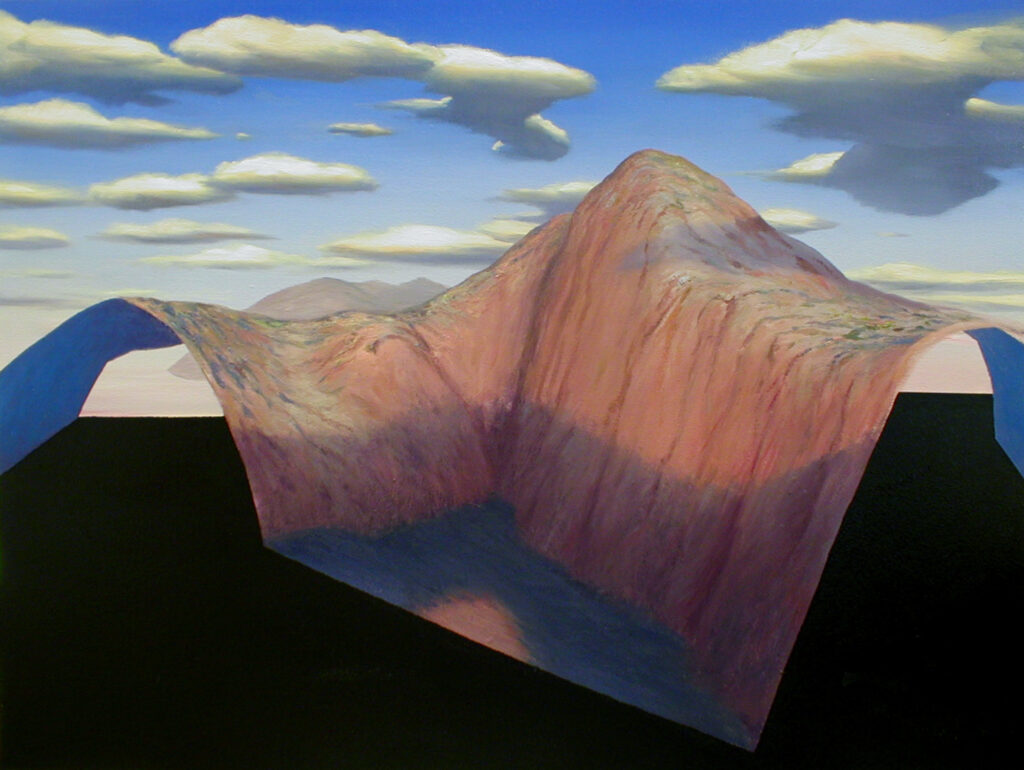

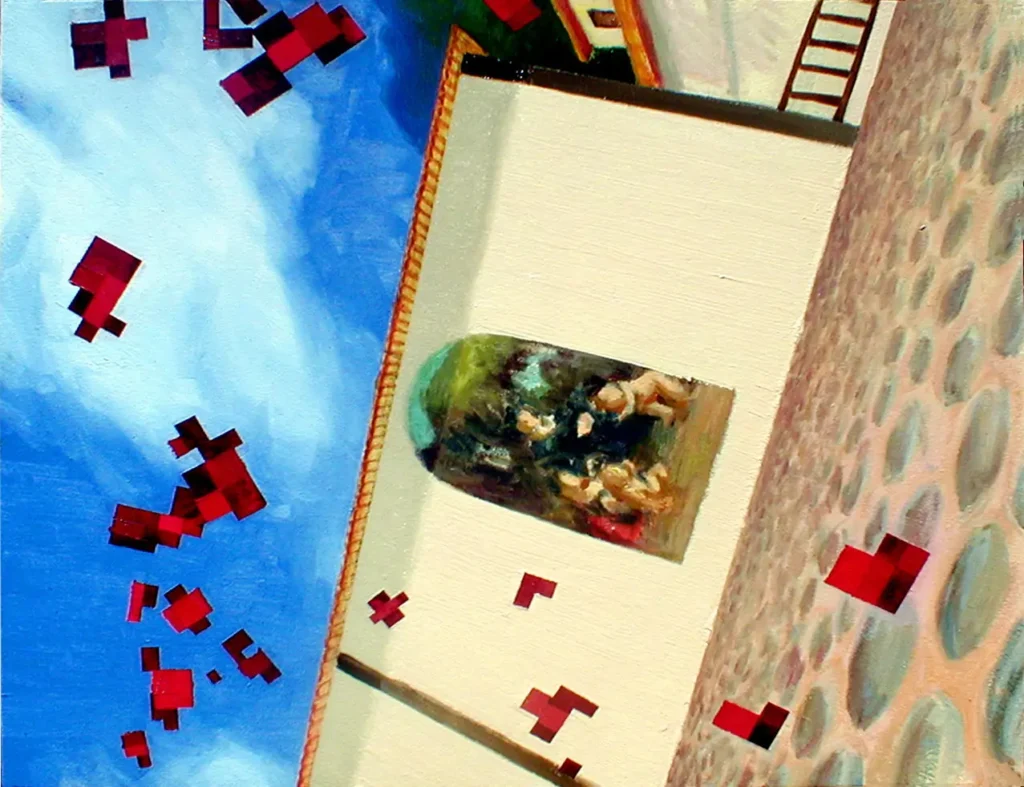

Swedish artist Kristoffer Zetterstrand’s early paintings, unofficially known as his noclip landscapes, are oil on fiberboard depictions of those same places you were never meant to reach. They are filled with vast skies, half-rendered landscapes, empty structures, distant horizons, and a strange, weightless stillness. The kind of quiet that exists only when you have slipped beyond the edge of a constructed world. these are not traditional landscapes in the plein-air sense, but images shaped by the act of exploration itself: drifting, hovering, moving through spaces that were built but never designed to be seen. If there was something resembling a social contract between you and the game being played, it’s been broken, and ahead lie no more promises of a cohesive experience.

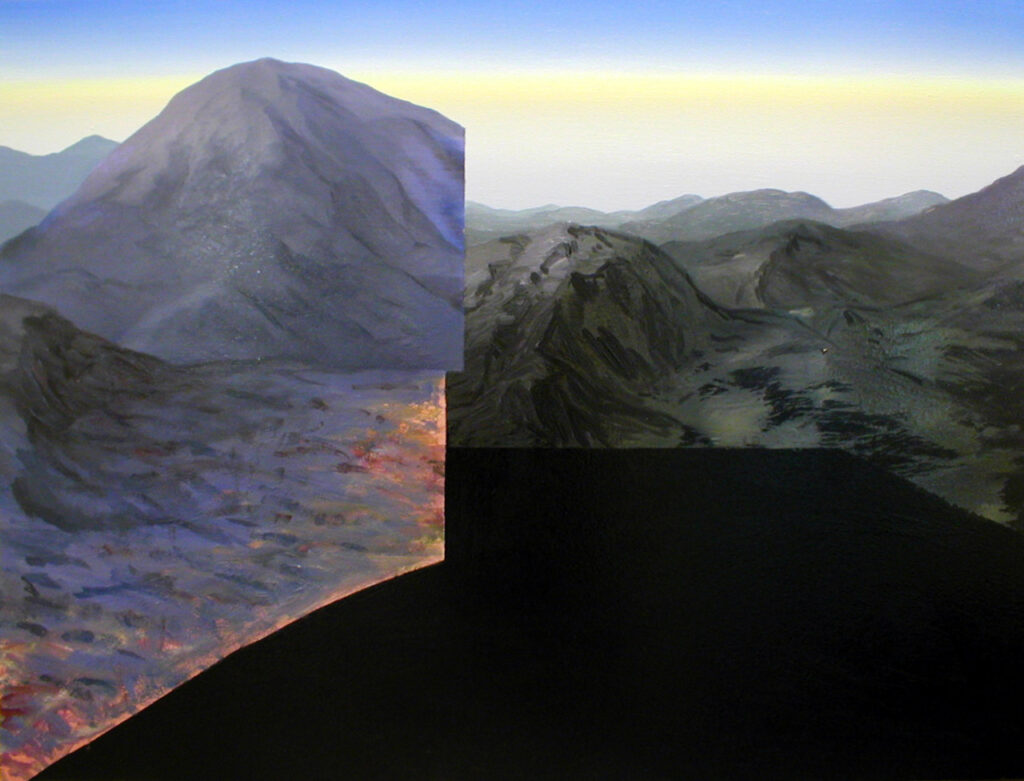

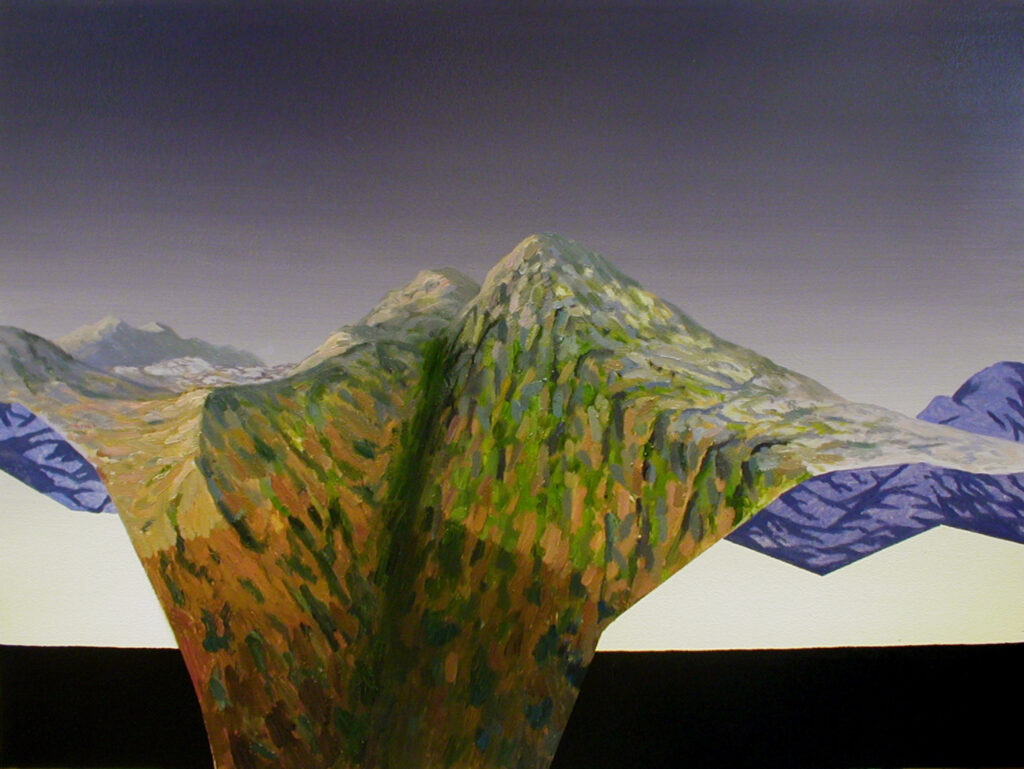

This sensation of being untethered inside a world is central to Zetterstrand’s early free-look paintings, a body of work painted at the beginning of his career in 2002 and made by freeing the camera inside 3D video game environments and capturing what lies beyond their intended boundaries, specifically the game most critical to the LAN party era of that time, Counter Strike 1.6. In these spaces, walls become thin skins, mountains reveal themselves as hollow geometry, and the horizon dissolves into light and texture. Zetterstrand translated these digital voids into oil paintings that resemble classical landscapes, yet quietly expose their artificial construction.

The origin of these works is unexpectedly intimate and strangely metaphysical. In 2002, while playing Counter-Strike, Zetterstrand was killed mid-round and suddenly found himself drifting outside the world of the level, suspended in what he later described as a kind of virtual near-death experience, in the game’s free-look Mode, a spectator state triggered after death, while the player awaits a respawn. In this mode, the player is no longer bound by gravity, walls, or objectives, but can fly freely through the map, observing living players, through mountains, and out beyond the edges of the constructed environment.

Past the final surfaces of the level there is nothing at all: no sky, no terrain, only flat blackness where the graphics engine has nothing left to render. Zetterstrand became fascinated by this split reality, in which the inhabited world of 3D geometry exists beside a void that is just as real to the machine. He then set to combine his formal training as a traditional painter at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm and these experiences, attempting to depict the moment where space dissolves into nothingness, treating the black fields not as emptiness but as the visible edge of a hidden system. In this strange afterlife of the game, the “dead” players are granted a godlike perspective, able to see both inside and outside the world at once, quietly observing its logic while waiting to be reborn or for the round to end. Ultimately, this led to the first gallery show of his career.

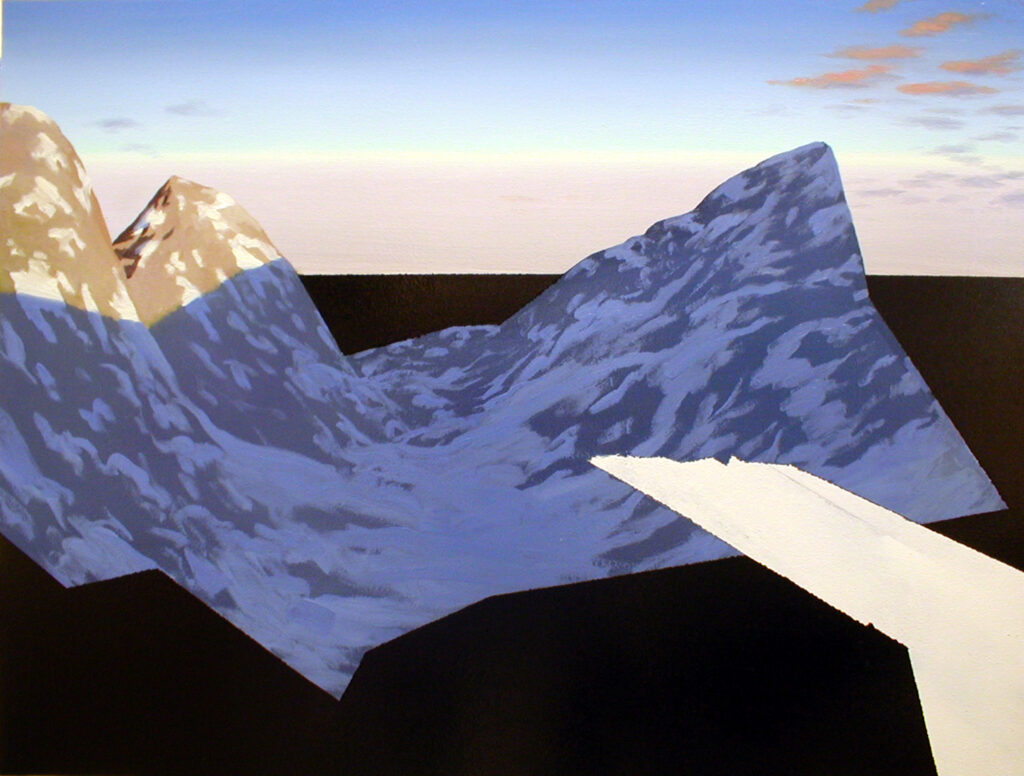

The next year, he followed up with another series of paintings and show, known as the Terragen series, this time depicting scenes from the eponymous 3D landscape generator program, often used by game developers and modders to create pre-rendered skybox backgrounds for Counter Strike and other games on Valve’s goldsrc engine. The landscapes are now completely devoid of gameplay, instead choosing to depict glitched and unfinished landscapes, mysterious hanging in a seemingly all-pervasive atmosphere.

The emotional charge of these works has deep roots in Romanticism, in particular Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. The famous painting places the viewer on the edge of an immense and unknowable world, suspended between presence and disappearance. Zetterstrand himself acknowledges this influence in a later painting featuring the famous subject of Friedrich’s painting, now standing on the mountain peak of a 2.5D diorama, seemingly from an old DOS game. When he was eventually hired by Mojang to include a series of his paintings for the game, Zetterstrand chose this painting in particular as well as some from his Noclip series as some of the options for players to hang in their homes inside the game, a full circle reference of how the virtual becomes reality and back again.

The Terragen and Free-Look vistas both create a similar psychological space, but with the human figure removed. The viewer becomes the wanderer, floating through a digital sublime that is both awe-inspiring and strangely empty. Where Friedrich’s mountains evoke the power of nature, Zetterstrand’s skies and floating structures suggest the scale of systems: virtual, architectural, and technological. Systems that now shape how we experience space.

At the same time, his paintings seemingly engage with the modernist tradition of distorting reality in order to understand it. In the early 20th century, Cubism and its related movements fractured perspective into overlapping viewpoints, an attempt to see one subject from multiple angles at once; Italian Futurism tried to capture speed, motion, and our disorientation from experiencing these extremes inside a static image. Zetterstrand applies these impulses to synthetic worlds. His landscapes often contain contradictory lighting, impossible depth, and geometry that collapses under scrutiny. What looks like a calm horizon reveals itself as a fragile construction, a highly linear set of hallways suspended in the air in front of a skybox, itself hanging above a black void.

Unlike traditional landscape painters who sought to document the external world, Zetterstrand paints the experience of moving through constructed environments, an early pioneer of the many genres that take heavy inspiration from childhoods and lifetimes spent in virtual spaces, whether they’re video games or social media, predating the work of contemporary artists highly sought-after in the art world such as Gao Hang. His scenes feel less like locations and more like moments of disorientation: the pause before a horizon loads, the silence after crossing a boundary, the eerie calm of standing inside a space that was never meant to be inhabited.

What makes his work especially resonant is how quietly it bridges centuries of visual culture. The Romantic search for the sublime, the modernist urge to fracture perception, and the digital age’s obsession with simulated worlds all coexist on his canvases. Zetterstrand uses technology the way painters once used optical devices and photographic references, as a way to see differently, and to reveal structures beneath appearances. A modern-day camera obscura for the age of rendered graphics.

It may seem unremarkable to paint landscapes in a video game, a pre-rendered space will always be inferior to its real-life analogue, yet there is a depiction of an experience unique to modern times that many have had, and its presentation not as pixels on a screen but as oil on a canvass grants that experience a kind of legitimacy: it affirms this common experience many have in experiencing the medium and moreover it is the latest iteration of a much older human impulse to transgress the boundaries of the given.

In one interview, Zetterstrand reflects on the inclusion of some of these paintings in Minecraft and their reception by players: “One thing I’ve heard from fans is that the paintings, in their weirdness, hint at something mysterious – a bigger world, something beyond, It’s quite interesting, because a basic idea in games is that you don’t want to break the immersion.”