A stolen white Porsche 911 in 1970s Yugoslavia turned an ordinary car thief into a legend. For several nights, an anonymous driver taunted police, electrified crowds, and briefly exposed the cracks in the socialist state’s tightly controlled order, leaving behind a story that still blurs the line between documented history and modern myth.

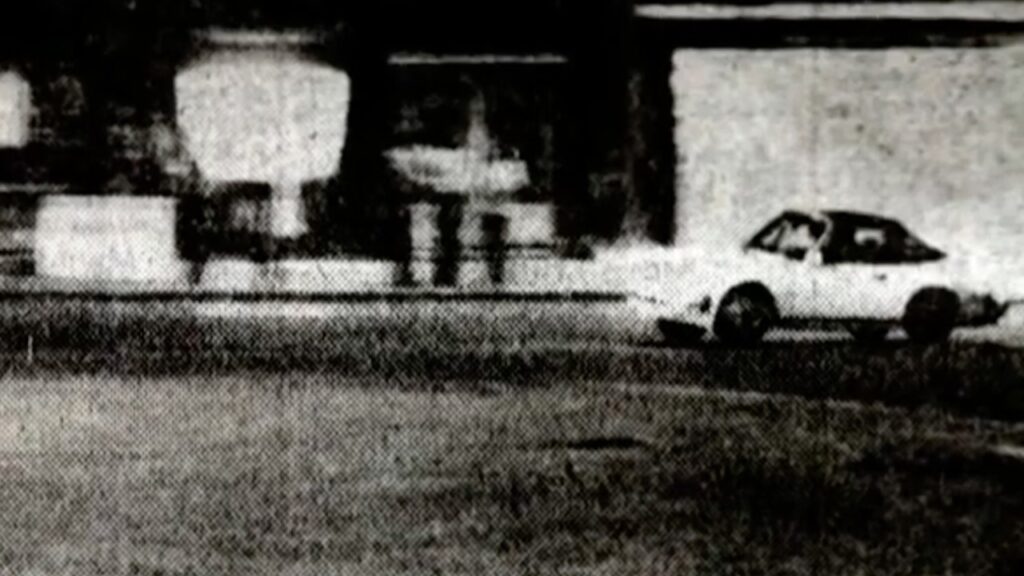

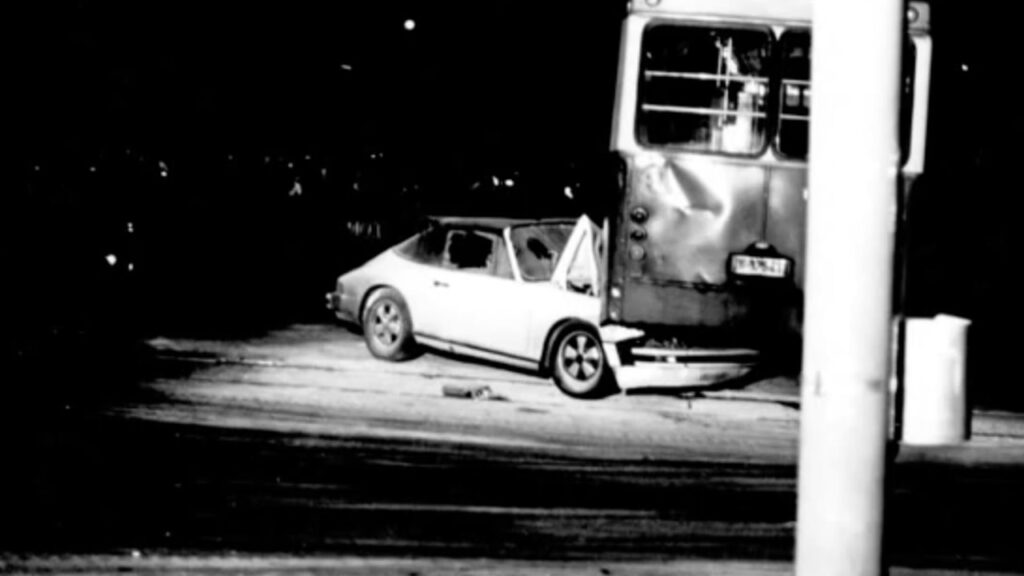

The black-and-white photograph of a vintage Porsche wedged grotesquely into the wheel well of a city bus looks, at first glance, like an ordinary traffic accident, tragic, perhaps, but unremarkable. In late-1970s Belgrade, however, that image marked the violent finale of one of the most enduring urban legends in Yugoslav history. What it captured was not just the wreckage of a stolen car, but the climax of the tale of a modern folk hero: the Belgrade Phantom.

The story is extraordinary precisely because it sits at the unstable boundary between fact and folklore. As the photos show, it is verifiably real, but has been obsessively retold, and endlessly distorted, an event so widely witnessed and repeated that no single, definitive version survives. If the vibe of films like Drive and Nightcrawler ever had a real-life equivalent, it would be this one.

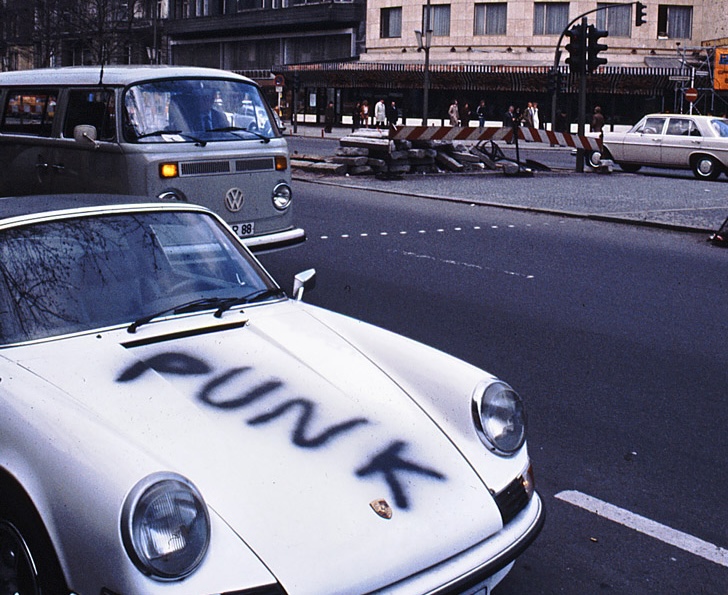

To walk through Slavija Square in Belgrade today is to encounter a city fully integrated into late capitalism: glass towers, relentless traffic, global brands. But in the late 20th century, the atmosphere was radically different. Yugoslavia, though more open than its Eastern Bloc neighbors, was still bound by socialist discipline, economic scarcity, and strict social expectations. Private cars were a rare breed as a means of personal transportation, to see one on the streets was already an uncommon sight, forget an exotic sports car.

Then, in 1979, a white Porsche 911 Targa began appearing on the streets after nightfall. Among the boxy Soviet Ladas and locally-made Zastava sedans crawling through Belgrade, the Porsche was a shock, an intrusion from another world. It careened through the city well above the speed limit, taunting any authorities it would come across before vanishing into the night. By day, it was nowhere to be found. Rumors spread rapidly: a foreign car, a phantom driver, a mysterious force that cannot be stopped by any man.

The car itself became the first source of myth. Some claimed it belonged to Goran Bregović, frontman of the legendary rock band Bijelo Dugme. Others insisted it had been stolen from the Danish Embassy. A more conspiratorial version suggested the owner was a criminal himself who dared not report the theft, lest he risk exposing his own ilicit sources of income, the only way one would expect to afford such a flashy car at the time.

The truth is more prosaic. The Porsche belonged to local Yugoslav tennis player Ivko Plečević, who had won it at a tournament in Berlin and left it parked in plain view in front of his home. Plečević, who was usually living in Austria as an instructor at a tennis school, happened to be staying in Belgrade for the summer. the night before he was due to leave back to his new home abroad, the theft occurred and he woke up to the sight of an empty parking space.

The thief was a professional, already well known in the city’s criminal underground. What he did next transformed a routine car theft into legend. Instead of stripping or selling the Porsche, as he normally would, the thief took it for a test drive. He enjoyed it so much he decided to keep driving it. Night after night. Always after 10 p.m. For anywhere between six to ten to fifteen nights, depending on who is telling the story, he raced through the city, deliberately drawing police attention.

His routes became predictable: In most cases, the route would be from Revolucije Boulevard (today’s King Aleksandar Boulevard), then Beogradski (formerly Boris Kidrič Street), and finally Slavija Square, a favorite spot of his, whose circular layout and multiple exits made it ideal for escape, because at that point, without fail, he would have several police cars in hot pursuit. Witnesses claim it was the police themselves who coined the nickname “Phantom,” as the driver seemed to materialize from nowhere and disappear just as suddenly. He reportedly phoned local radio stations in advance, announcing where he would drive that night. When asked why he did it, he is said to have replied: “I know it’s a crime and that there will be consequences. But when I’m in the car, I don’t want to get out.”

The news spread like wildfire. As the story grew, romantic embellishments followed. Some stories claim the driver left a rose at Slavija Square each night for a woman named Vesna, and went on his nightly rides purely to attract her attention. No one could say who she was or whether she even existed. Residents of the city’s neighborhood of Bulbuder in the region of Zvezdara proudly insisted she not only exists but was one of theirs. Like most details of the Phantom’s life, Vesna probably hovers somewhere between reality and invention.

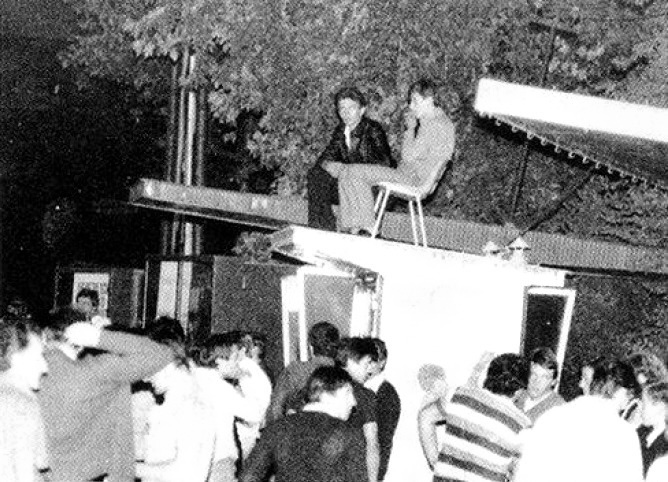

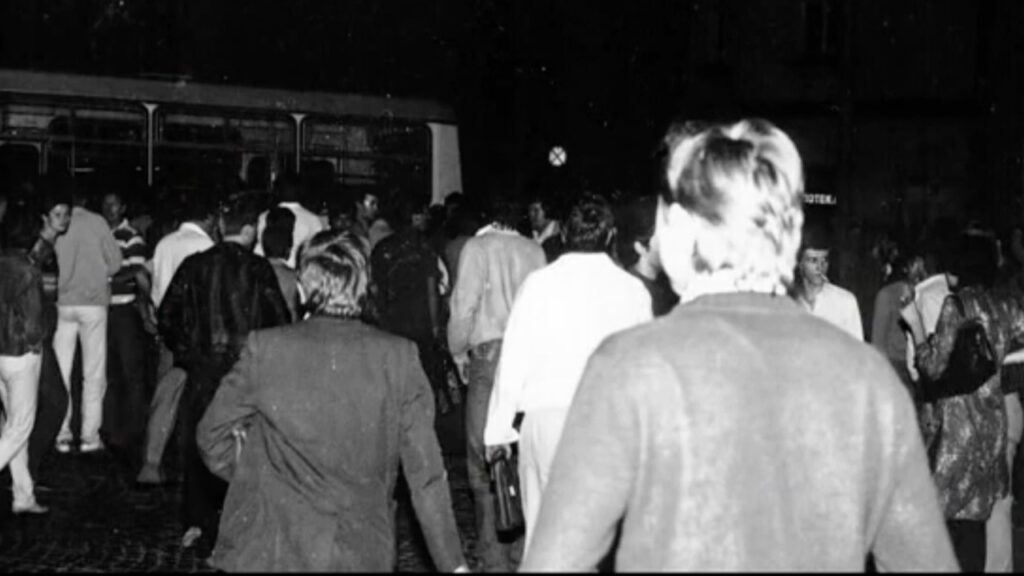

What is certain is that the public embraced him. People began gathering at Slavija Square at midnight with folding chairs, radios, snacks, and thermoses, listening closely for the driver’s call-ins to the radio stations and waiting for the nightly spectacle to unfold. Crowds reportedly swelled into the thousands, sme climbing onto roofs to get a better view. Sure enough, their patience would pay off, and the mysterious driver would treat his new audience to the sight of an exotic car dashing across the roundabout, taking three laps around before leaving at any one of the roundabout’s many exits, always just out of reach of the authorities.

In a tightly controlled society, the Phantom’s defiance was intoxicating. He was outrunning the police, and humiliating the entire system while he was at it. It was never proven that the driver’s actions were meant to be a protest against said system, but the adoring public took it as such anyway.

Belgrade’s police were hopelessly outmatched. Their Zastava 101s and Fiat 1300s faded into the Porsche’s rearview mirror. Desperate, the police allegedly attempted to stop the driver through other means, namely by issuing heavy fines against the Porsche. But without the identity of the driver, those threats were not worth the paper they were printed on.

The police were exhausted. Despite the growing crowds and media attention, no one still knew who was actually behind the wheel, or at least no one would come forward to volunteer that information. Various journalists attempted to capture the driver with their cameras, but in an era before widely available good quality film, high-speed photography, or automated traffic cameras, the Phantom remained faceless.

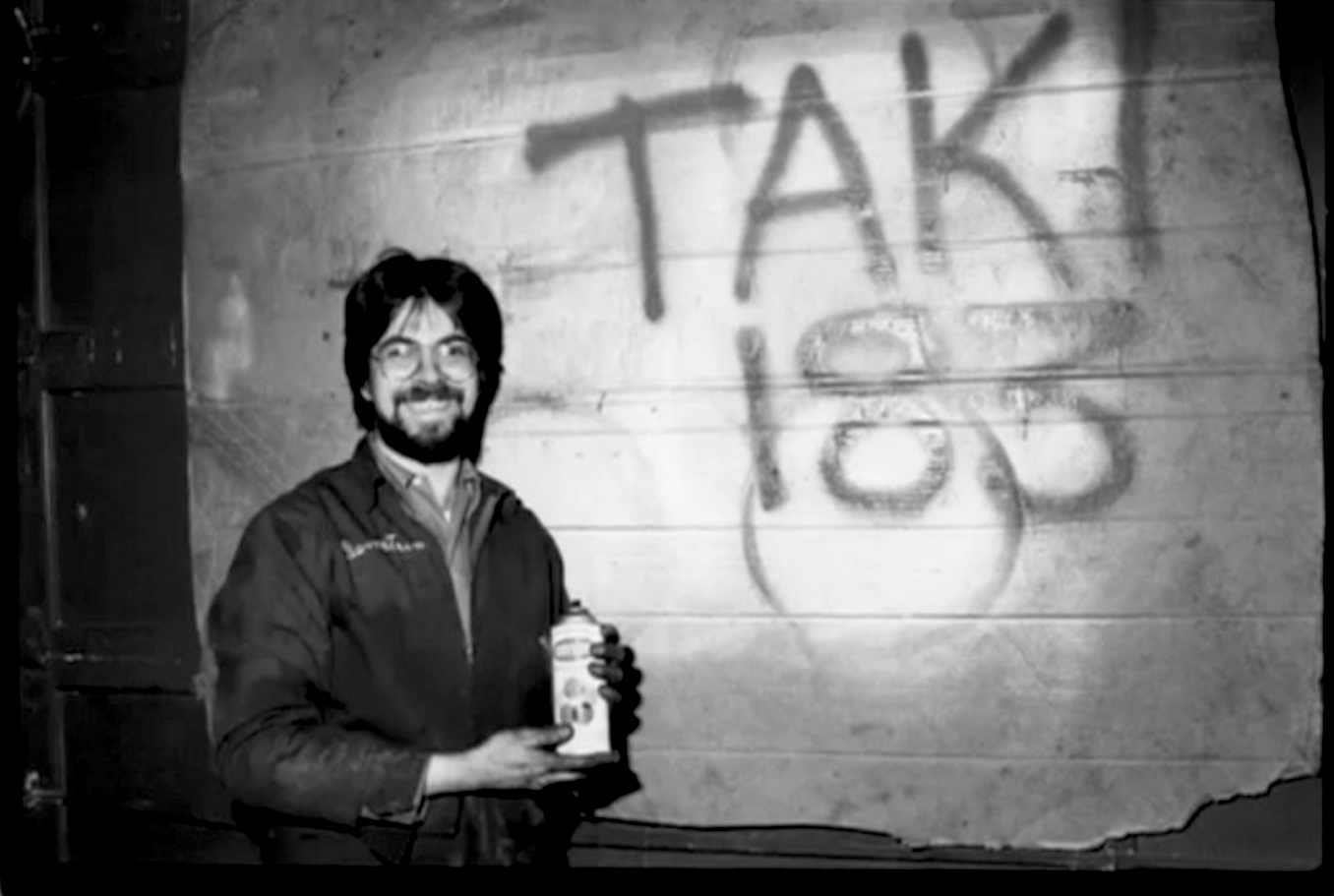

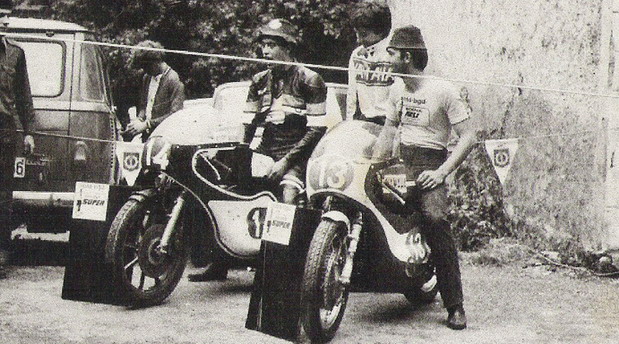

The first and only clear glimpse came only through the persistence of Ilija Bogdanović, a Jat Airways flight steward who took up photography as a hobby on the side. Armed with a serious camera and high-sensitivity film he had recently purchased after a flight to New York, Bogdanović correctly identified Slavija Square as the best vantage point and assembled an improvised support team. He enlisted the help of Vuk Tomanović, a professional Yugoslav motorcycle champion (and participant in the Yugoslav Grand Prix that same year) who was on standby, ready to chase the Phantom, should the need arise. Additionally, Bogdanović would ride with a taxi-driver friend who would listen in to the radio in his car for updates.

For several nights he managed only blurred shots of the speeding Porsche, until finally, from just a few meters away, he captured the driver’s face. On his way home to develop the film, Bogdanović hesitated, despite having the evidence he sought. Publishing the photograph would almost certainly lead to the driver’s arrest, and he wanted no part in that responsibility. In the end, he kept the image to himself and chose not to present it to the authorities. The Phantom had been seen, but not betrayed. Unfortunately, this did little to prevent the catastrophe that would soon occur.

The Phantom’s nightly escapades were no longer treated as a spectacle but as a growing embarrassment. The news had supposedly reached Josip Broz Tito, the iron-fisted leader of Yugoslavia of the time, who was away in Cuba for the Non-Aligned Movement summit in Havana. His return to Yugoslavia imminent, high-ranking government officials began to put pressure on the police chiefs.

The authorities, fearing Tito’s wrath, were desperate to catch the driver. An order was issued, some say directly from Tito himself, to apprehend the driver dead or alive. One of the police force’s best detectives, reputed to be a skilled driver, attempted to intercept the driver using a Ford Granada Mk II, yet he was still unable to keep pace and the Phantom escaped yet again. During the day, they attempted to search the city, expecting to find the car parked somewhere, to no avail.

Eventually, the police hatched a plan. If they could not catch up to him, they would slow him down. They considered shooting the car’s wheels, only to back off, fearing that they might hurt bystanders from the collateral damage of the bullets or the car losing control. Instead, they came up with a more passive strategy.

Naturally, the trap was set at Slavija Square. Fire trucks were deployed to drench the streets with water, turning the asphalt slick. Two Ikarbus city buses were positioned to block the road. The onlookers were powerless to prevent the trap as they had no means of communicating with the mysterious driver. As expected, the Phantom entered the roundabout, and immediately lost control on the wet ground and crashed head-on into the wheel well of one of the buses. Despite the driver’s best efforts, no amount of skilled driving could avoid two buses blocking the width of the road.

As the gathered crowd immediately ran to check on the driver, witnesses claim they deliberately stepped in to shield him from the police. The driver himself, evidently unscathed, squeezed out of the door of the car and vanished into the crowd. Estimates of the crowd range wildly, from a few thousand to as many as 10,000. Once again, the myth eclipses documentation. What is certain is that night, the Phantom once again, evaded capture. The chase was over, but the story wasn’t.

Two days later, the police received an anonymous phone call. It is suspected the identity of the caller was someone familiar to the Phantom, likely someone who was a member of the same car theft ring, or some other accomplice whose motive was to jealously remove a high-profile competitor. The individual likely recognized him in the crowd during the night of the crash and made the call. In the end, the Belgrade Phantom was caught.

The man behind the wheel was revealed to be 29-year-old Vlada Vasiljević, nicknamed Vasa Opel, due to his particular preference of stealing German Opel cars, as well as Vasa Ključ (“Vasa the Key”), supposedly famed for his ability to get into virtually any car. He was well known in the Belgrade criminal underworld and had a peculiar habit: stealing vehicles simply to drive them at extreme speeds at night, then returning them undamaged, sometimes with a full tank of fuel.

He was sentenced by the District Court to two and a half years in Belgrade’s Centralni Zatvor (“Central Prison”) for the theft of two cars and for endangering traffic safety. There, he behaved impeccably, and was well respected by the other prisoners, his reputation having preceded him. Following a visit from his sister, he escaped out of a window. To add one final humiliation towards the police, he would voluntarily return days later, claiming he needed to take one more night drive so the police wouldn’t think they’d won. For that, he received 30 days in solitary confinement. Serving out the rest of his sentence in peace, he was released in 1982.

Shortly after returning to freedom, at age 32, Vlada died in a highway car accident near Požarevac, along with a friend named Vidra. He was a passenger in a white Lada, also possibly stolen, driven by the friend when it collided with a truck ahead of them, after it had unexpectedly braked. The Lada was then sandwiched between it and another truck that also failed to slow down in time. Vidra died immediately on impact, while Vlada passed away in the hospital a few days later. Accounts of the aftermath differ wildly.

One conspiracy claims the police tampered with the brakes as retribution for the embarrassment inflicted on them, another claims the police paid Vlada a visit in the hospital to finish the job, and still others say the entire accident was a setup by the cops, or even staged by Vlada himself so he could escape the public eye and retreat back into obscurity.

Though reports of the event point to things like the alleged circumstances of Vlada’s hospitalization – that only one doctor attended to his injuries (despite their severity) and the fact his relatives were forbidden from visiting him – no theory of murder has ever been conclusively proven. What remains certain is this: a man stole a Porsche, drove it through Belgrade for days, humiliated the authorities, captured the imagination of an entire city, and crashed spectacularly. The rest is legend.

Legendary enough that in 2009, the story was immortalized in The Belgrade Phantom, a film directed by Serbian-American Jovan B. Todorović. But long before cinema claimed him, the Phantom had already become something rarer: a modern myth born from speed, spectacle, and a fleeting taste of freedom in repressive times.

The infamous car itself (or what remained of it) was eventually returned to its owner. Plečević, despite by then being well aware of the car’s legendary status, did not opt to repair the damage and instead sold it to a collector, its further fate left unknown.

Whether Vlada Vasiljević was a folk hero making a stand against an oppressive government or simply a gifted car thief is ultimately beside the point. For a brief moment, in a city starved of defiance, he made thousands believe that the system could be outrun.