Willingly spending two months in a Mexican prison and collaborating with the inmates, artist Scott Campbell built tattoo machines out of whatever was available, but they were never meant to last. In his project Things Get Better, they became a meditation on ingenuity, constraint, and survival.

Scott Campbell’s 2013 project Things Get Better is introduced on his website with a single, disarmingly plain sentence: “Two months, 17 Walkman motors, and whatever I could find inside the walls of a prison in Mexico.” It’s a simplification, but it also accurately gets across what actually happened to create one of the most ingenious projects inside contemporary tattoo culture of the last 20 years. What began as an act of curiosity, Campbell’s interest in prison tattoo culture, ultimately became a meditation on ingenuity, identity, and the way creativity behaves under extreme limitation.

As one of the world’s most high-profile tattoo artists, Campbell’s first celebrity client was Heath Ledger, and grew to include a star-studded roster of names including Robert Downey Jr, Marc Jacobs, Courtney Love, Howard Stern, and Sting, to name a few. However, his early career in San Francisco working at a tattoo shop run by a meth dealer while moonlighting as a copy editor for Lawrence Ferlinghetti at the famous City Lights bookstore tells us he was never a stranger to going low when he wanted to. In his own words, “I’ve tattooed murderous bikers who kill people for a living and Jennifer Aniston – and everything in between.”

Naturally, the choice to willingly spend roughly two months inside a prison in Mexico City, an environment defined by restriction, monotony, and a bit of corruption, seems like a natural creative choice. The goal? Get to know the general population and work with them to build tattoo machines with whatever is available, give them tattoos, and record the results.

Prison life, by design, is a place where individuality is largely stripped from the inmate; tattooing, in this context, takes on a gravity that is largely absent from the mainstream tattoo world. Tattoos are no longer accessories or status symbols, they are assertions of selfhood. Campbell understood this and wanted to see it for himself. “I didn’t really know why I was there … I just went there out of my own curiosity and ended up becoming friendly with a lot of the inmates and when they heard I was a tattooer, they all wanted to get tattooed so we started building these little Frankenstein tattooing machines out of whatever we could find.”

Campbell did not enter the prison as a formal artist-in-residence or with institutional backing. Mexican prison regulations, more flexible and more negotiable than those in the United States, made the project possible, though not straightforward. He could not bring professional tattoo equipment inside, so he did what incarcerated tattooers around the world have always done: he improvised. According to the artist, it took some creative workarounds to get everything into place. “I’d buy the warden a nice bottle of scotch and got his secretary some flowers and that made things a lot easier. I donated all these things to the prison, like VCRs and guitars, and once we got onto the other side we’d take them all apart and make them into machines.”

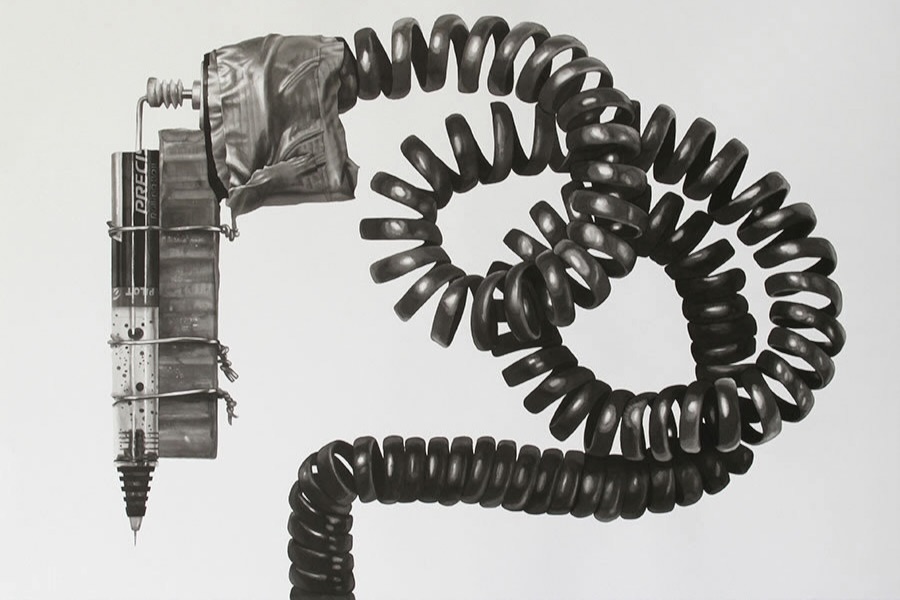

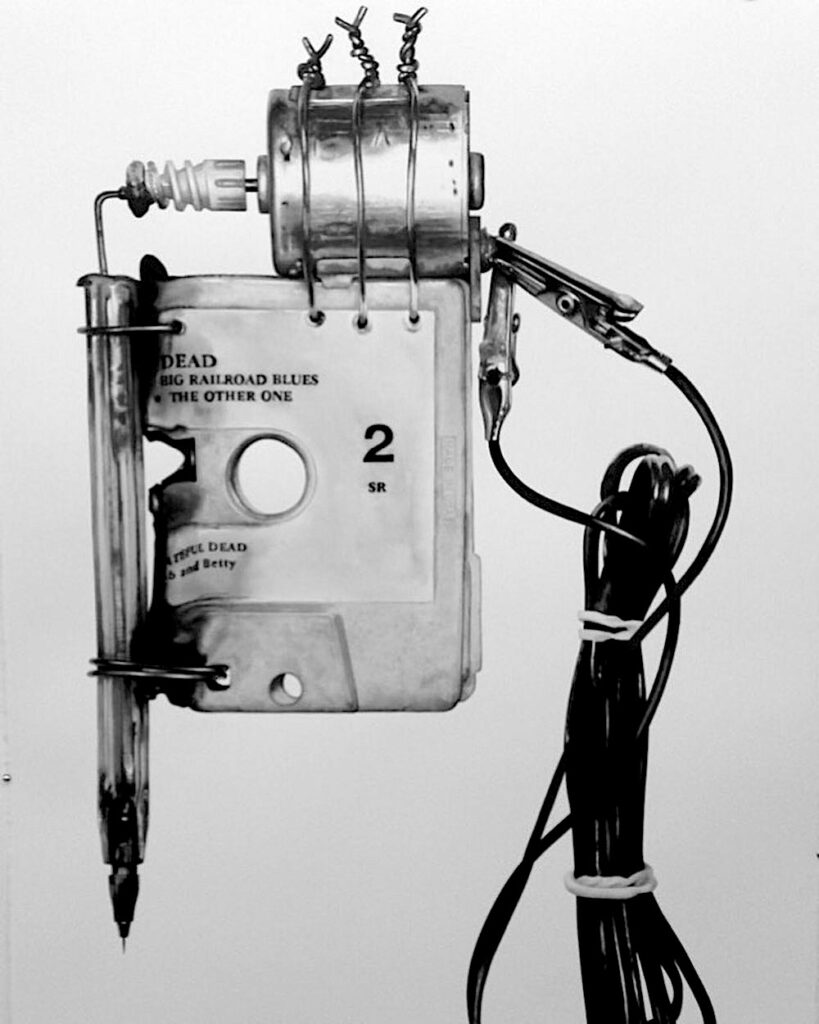

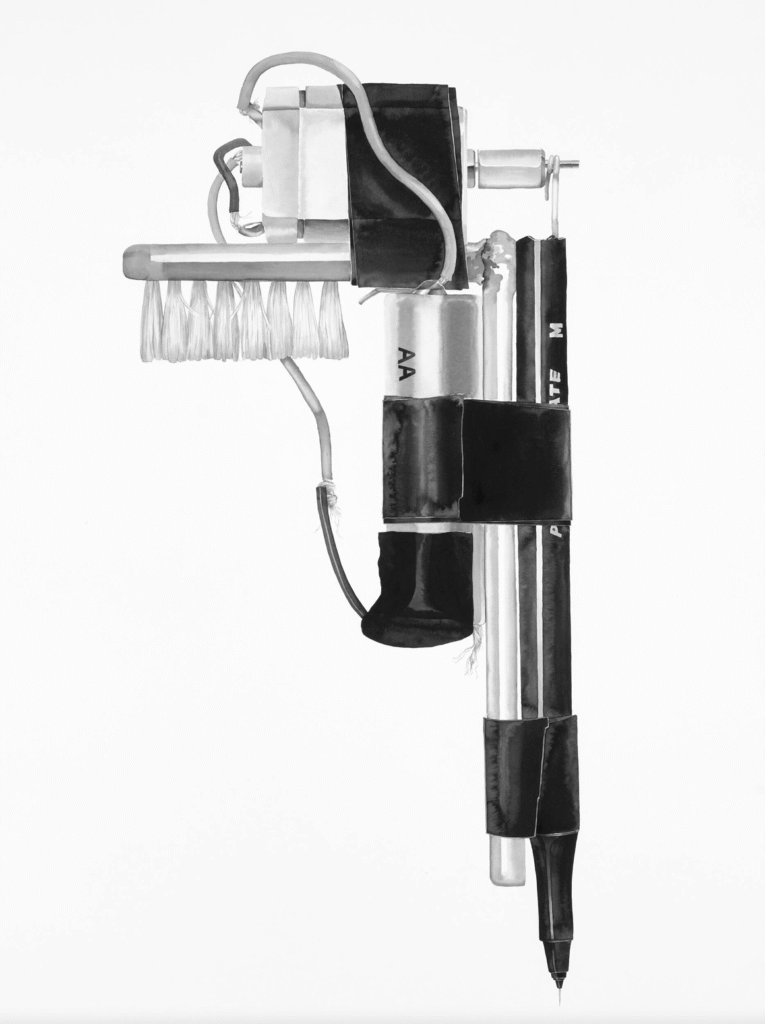

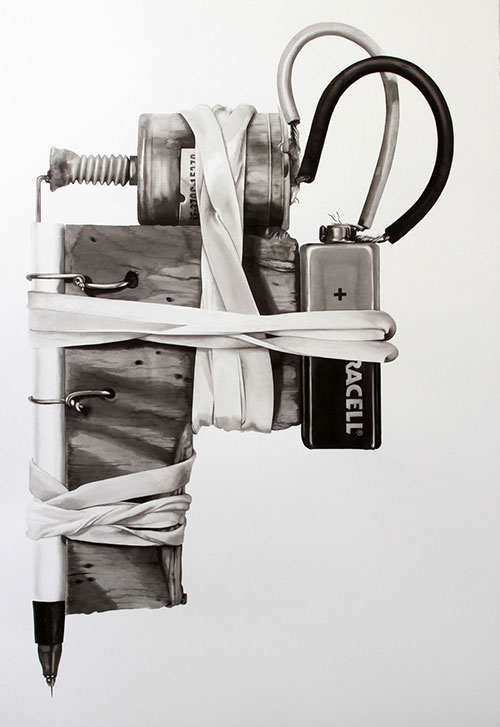

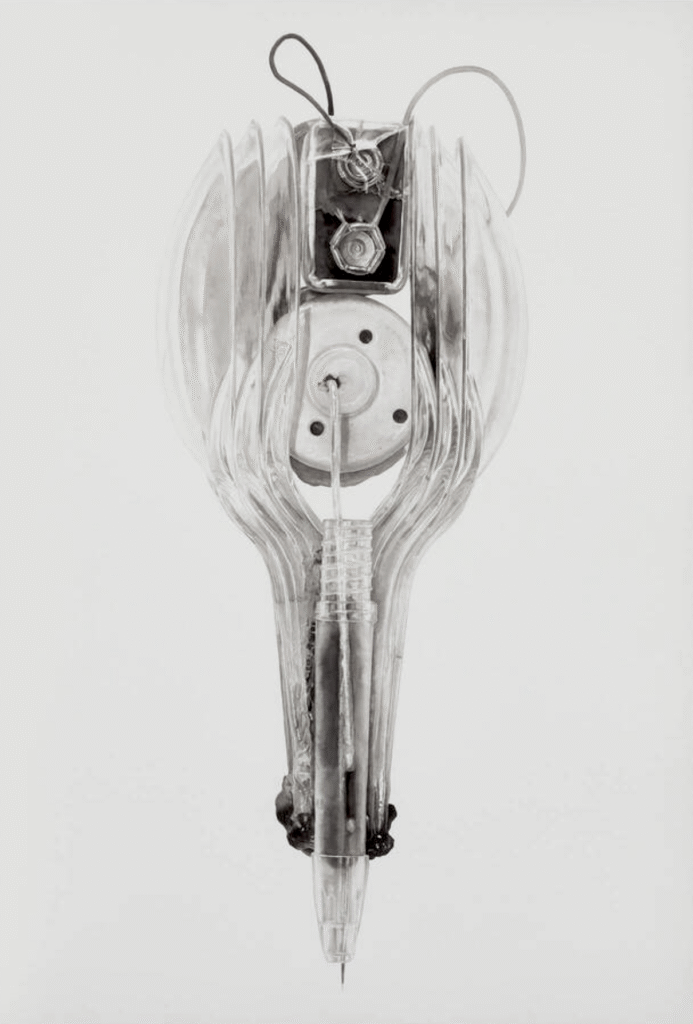

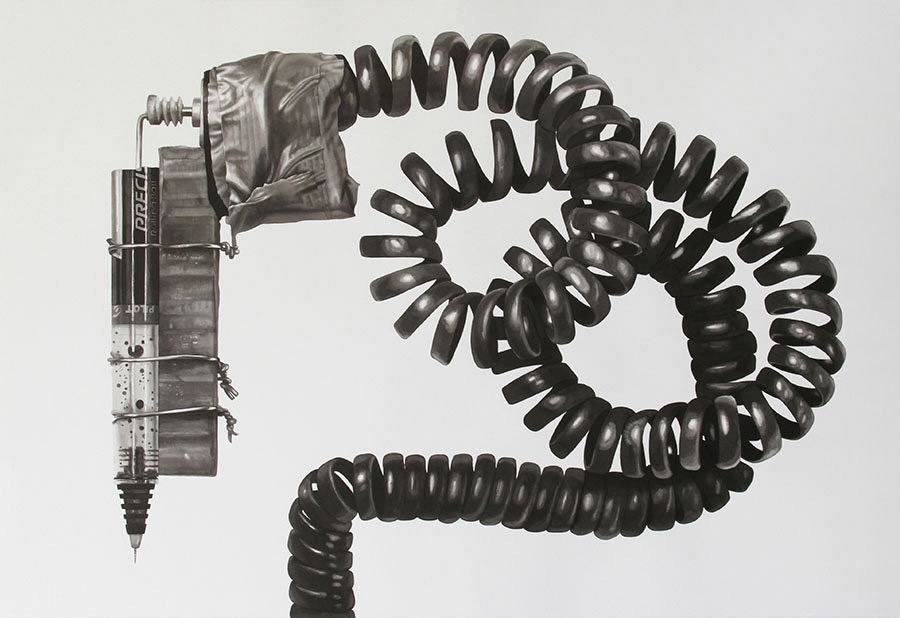

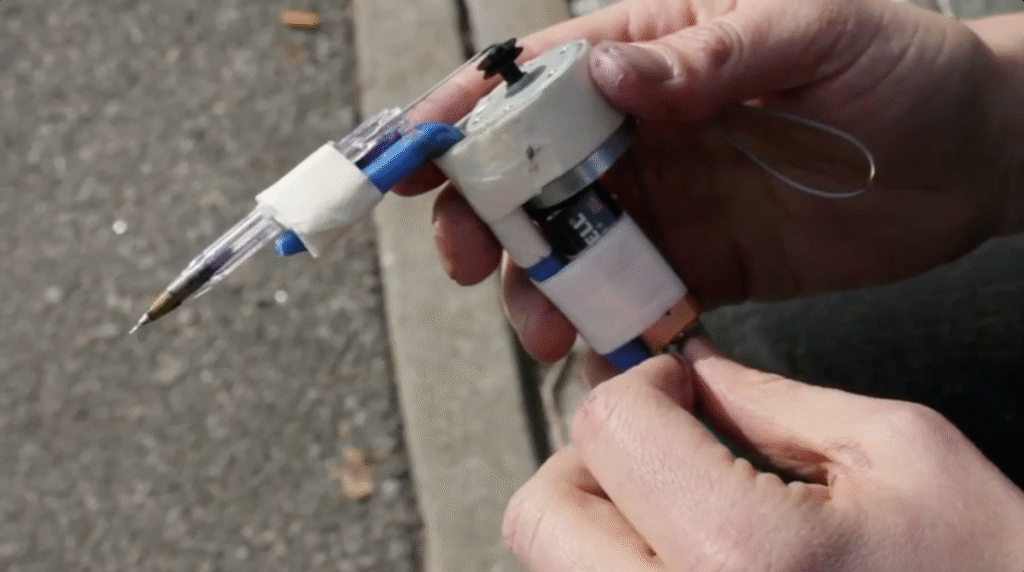

The guards having turned a blind eye, Campbell got together with the inmates and built functioning tattoo machines from whatever materials were available or could be quietly introduced as donations, sometimes scavenging second-hand stores and salvage yards for any electronics he could find. Electric motors were scavenged from Walkmans and electric razors; needles were fashioned from guitar strings and safety pins; grips emerged from toothbrushes, plastic utensils, lighters, and even a melted half of a Grateful Dead cassette tape, with everything often held together with nothing but packing tape and a prayer.

More than a technical exploration, the project took on a social element. The machines were built collaboratively. More importantly, each machine was made for a single individual and then discarded. This was partly practical, minimizing the risk of cross-contamination in an environment without proper sterilization, but it also imbued each object with a singular, almost ceremonial character, tailored to every individual receiving a tattoo. These were temporary instruments to facilitate an exchange, existing only long enough to leave a mark on one body.

Campbell began to notice something unexpected: the machines themselves were compelling objects. Jury-rigged and fragile, held together by rubber and tension, they reflected a kind of forced inventiveness that felt both brutal and elegant. He referred to them as “Frankenguns,” a term that captures their stitched-together quality as well as their uneasy vitality. They were machines built under pressure, but also artifacts of care, skill, and communal problem-solving.

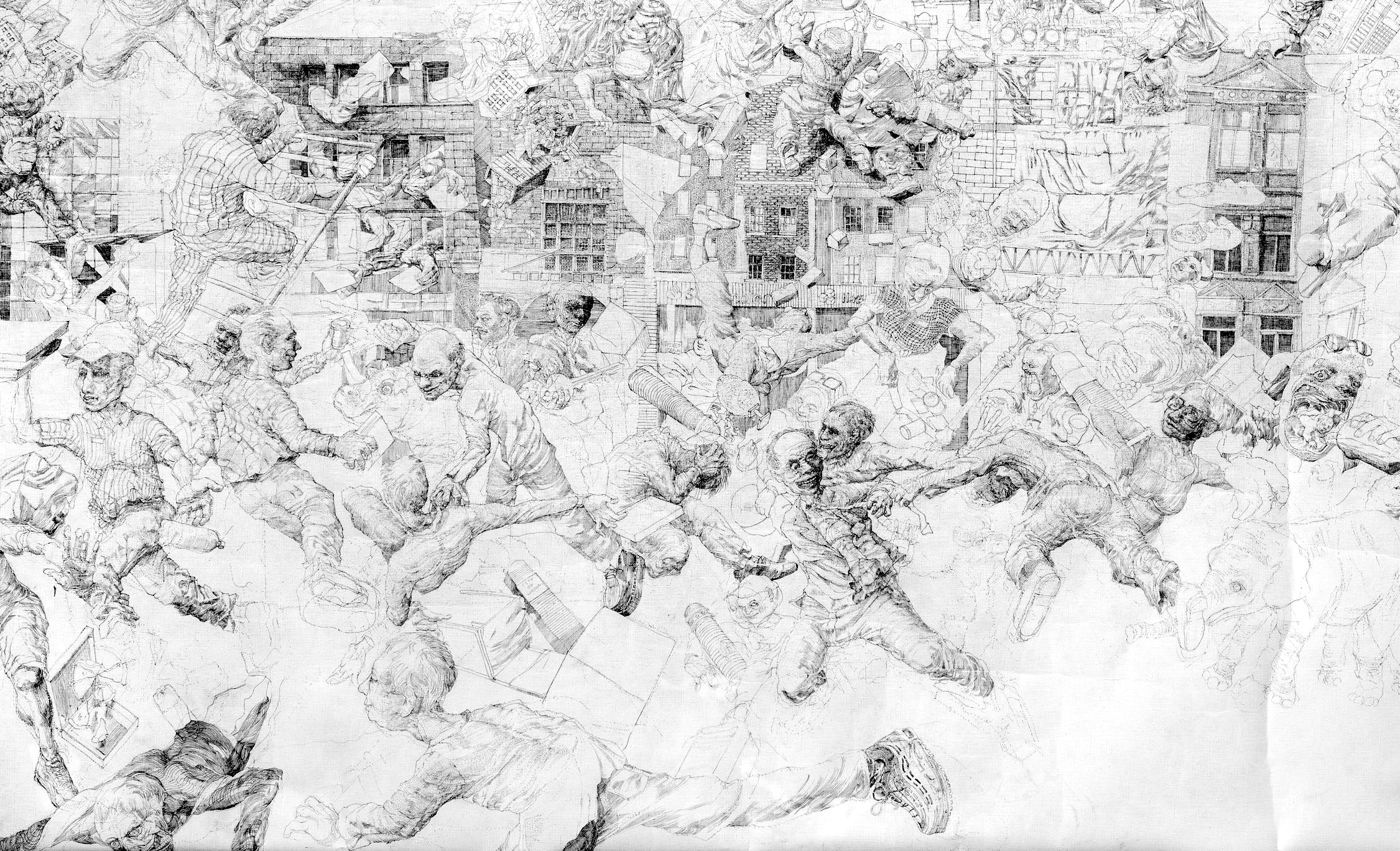

After leaving the prison, Campbell returned to these objects, not physically, but conceptually. The result was Things Get Better, a series of large-scale watercolor and black ink paintings depicting the improvised tattoo machines in isolation. Removed from the prison environment and the bodies they once marked, the machines become something else entirely: studies in structure, balance, and adaptation.

Executed primarily in black ink and watercolor, the paintings avoid drama or embellishment. This restraint is crucial. Campbell chose watercolor precisely because of its unforgiving nature: once a stroke is laid down, it cannot be erased or disguised. The medium mirrors the conditions of both prison tattooing and incarceration itself, there is no undo function, no clean slate.

Visually, the machines begin to resemble architectural fragments or skeletal systems. Wires loop like tendons; motors sit like hearts; bindings read as ligaments holding the entire organism together. Some works feel almost diagrammatic, while others verge on surrealism. Scale plays a role here as well: enlarged to six by eight feet in some cases, the machines lose their original hand-held intimacy and take on a monumental presence. What was once improvised and disposable becomes imposing and permanent.

This transformation from tool to symbol, is central to the project. Campbell is not romanticizing prison life, nor is he glorifying hardship. Instead, he isolates a specific phenomenon: how constraint sharpens invention. “The machines really became beautiful symbols of the ingenuity and humanity that you find in a place that’s that oppressive.” In the absence of proper materials, creativity becomes intensely pragmatic. Solutions must work, not merely look good. A tattoo machine that fails mid-line is not a conceptual experiment, it is a problem that must be solved immediately. “There has been more than one occasion where people have come in for studio visits and they’ve walked out with a bleeding arm or ankle.” Imperfection is a recurring theme throughout the project. Tattoos made with improvised machines bleed. Lines wobble. Healing is unpredictable. Campbell does not deny this; he embraces it. “Perfect isn’t always the point,” he has said.

This emphasis on problem-solving places Things Get Better in conversation with design, engineering, and even architecture as much as with tattooing or fine art. Campbell has spoken about how, over time, he began to approach the machines themselves as works of art, arranging materials for visual rhythm as much as for function. “ ‘They were reflective of making things out of such limited resources, and I wanted to give them more of a presence and power. Soon I was building the machines with a painting mind. I would make these constructions as compositions, incorporating different materials or repeated parts to create a motif.”

The project also marked a conscious rejection of the contemporary tattoo industry’s growing slickness. By 2013, tattooing had become thoroughly mainstream: televised competitions, celebrity tattoo artists, branded studios, and social media-friendly aesthetics dominated the field. Campbell, who founded the Brooklyn studio Saved Tattoo, was deeply embedded in that world. Things Get Better emerged, by his own admission, as a corrective. “I was looking for a way to fall in love with tattooing again,” he said. Prison tattoo culture, with its risks, imperfections, and stakes, offered that renewal.

Exhibited at OHWOW Gallery (now known as Moran Moran) in Los Angeles, the series was presented not as documentary evidence but as a cohesive body of fine art. There are no bodies in the paintings, no prison interiors, no overt narrative cues. Instead, viewers are left to infer the conditions that produced these objects. This distance is deliberate. By stripping away context, Campbell allows the machines to function as universal symbols of adaptation, objects that are not from any one particular part of the world, but instead could belong to any environment where resources are scarce and ingenuity is mandatory. He even proved this point in a video with Casey Neistat, where he created a tattoo gun from parts he found or bought while walking around New York, well worth watching.

The title Things Get Better is often read ironically, but it resists easy cynicism. It does not promise progress or redemption; it states a simple, almost stubborn belief in human adaptability. In places where systems fail or resources disappear, people still make things work. They still build, mark, communicate, and assert their identities.

Ultimately, this project sits at an unusual intersection of tattoo culture, conceptual art, and social observation. It neither sensationalizes prison life nor sanitizes it. Instead, it isolates a single, telling phenomenon: the transformation of discarded materials into meaningful tools, and then into art. By elevating improvised tattoo machines into painted studies, Scott Campbell reframes “doing more with less” or constraint itself as a generative force, one capable of producing not only survival, but beauty, structure, and quiet resilience.

In doing so, the project asks an uncomfortable but necessary question: what does creativity look like when comfort, abundance, and polish are removed? The answer is stripped down, improvised, imperfect, and profoundly human.