In 1974, Soviet authorities used bulldozers, arrests, and violence to destroy an unsanctioned outdoor art exhibition, only to ignite an international scandal and turn it into one of the most important moments in Russian art history.

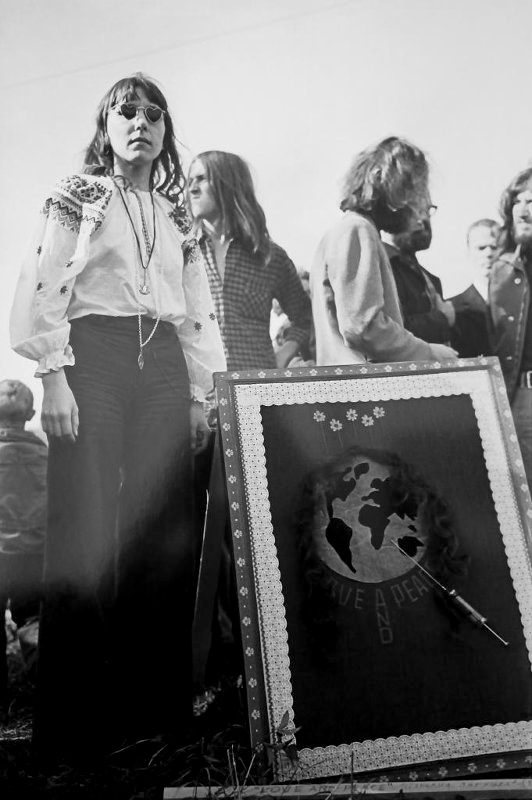

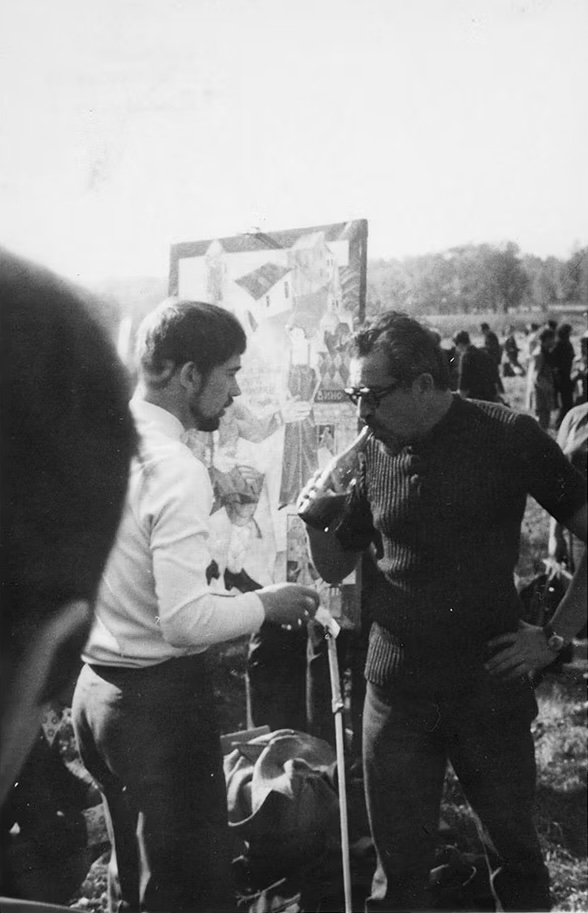

On a vacant lot near Moscow’s Belyaevo metro station, a group of nonconformist artists staged what would later become known as the so-called Bulldozer Exhibition, named not symbolically, but quite literally. The canvases were mounted on improvised stands made from scrap wood, and the audience, numbering only a few dozen, consisted mainly of fellow artists, friends, family members, and a small contingent of Western journalists. Though modest in scale, the event carried outsized symbolic weight, something even the Soviet government itself seemed to recognize. Within minutes of the event opening, police would intervene, destroy the works on display using bulldozers, arrest the organizers, and chase attendees and journalists away with firehoses, bringing the exhibition to an abrupt and violent end.

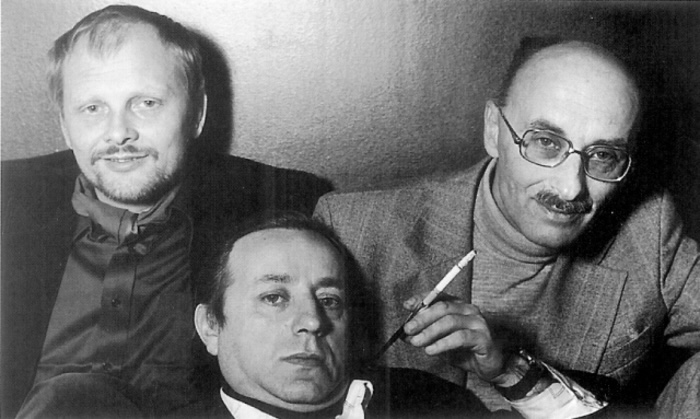

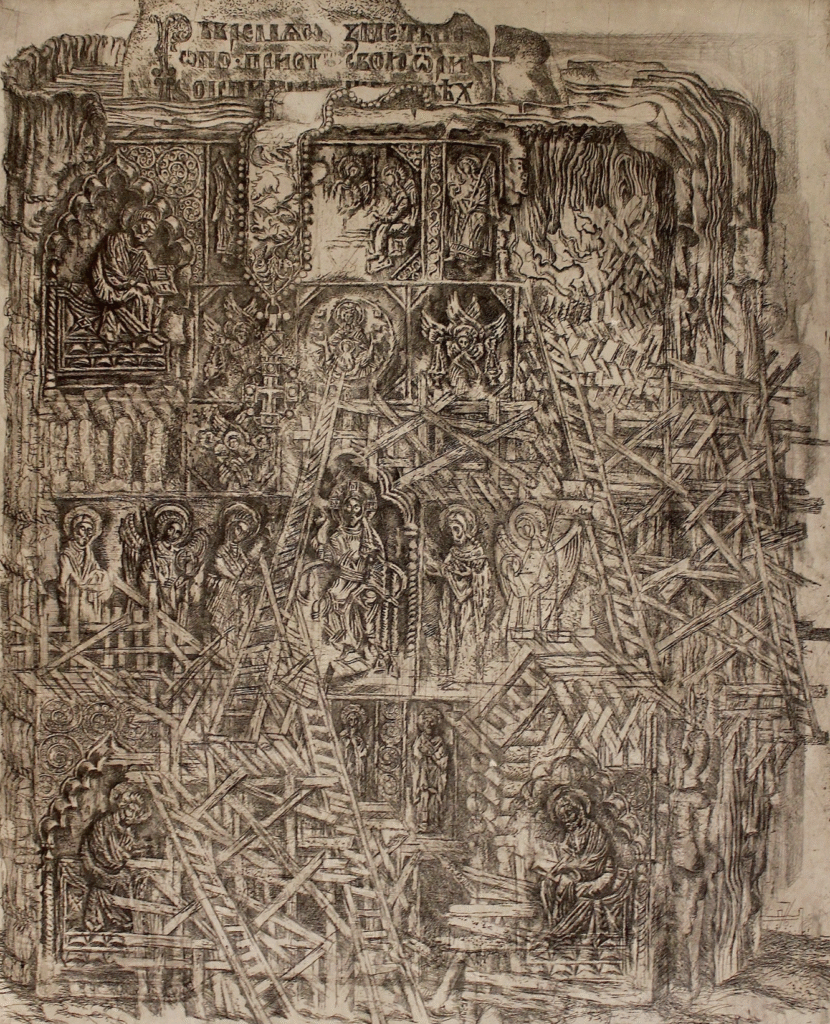

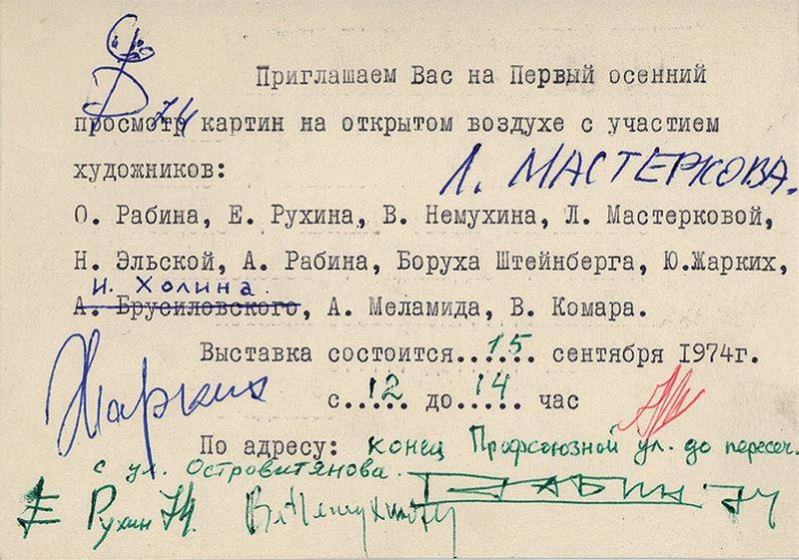

Before that infamous day became reality, it was merely an idea born in the apartment and basement studios of Moscow’s “nonconformist” artistic underground, so called because its artists were not members of any official artists’ organization and lacked state approval to exhibit publicly, usually due to the conceptual or abstract nature of their work. Initially masterminded by artists Oskar Rabin, Yuri Zharkikh, and art collector Aleksandr Glezer, the exhibition eventually came to include many more associated with the Soviet nonconformist scene, names that today the Russian and post-Soviet art world often regards as among the greatest unsung creative figures of the late twentieth century. In their own time, however, they were branded troublemakers and threats to the status quo.

What, then, led to such severe opposition from the government toward unofficial art, and why was even a single attempt at public visibility met with such a harsh response? The roots of this dynamic between state and artists trace back to the Stalin period, specifically April 23, 1932, when the decree titled On the Restructuring of Literary and Artistic Organizations was passed. This new order dissolved all independent artists’ groups (i.e. those not under state control), centralized artistic activity under the Union of Artists, and outlawed all styles except Socialist Realism, favored by Stalin himself.

The style marked a complete break from the previous decade of Soviet orthodoxy, which had relied heavily on abstract and constructivist aesthetics. Where art had once been conceptual and revolutionary, the new style became fully representational, devoid of abstraction, and encouraged subject matter glorifying historical achievements or the labor and life of the Soviet people. As art historian Anastasia Kopaneva notes, those outside the system were labeled “parasitic” and subjected to repression. Though an underground culture persisted, the need to publicly show work in order to be seen at all, made complete invisibility impossible, and confrontation with authority became inevitable.

The newly branded unofficial artists of the Soviet Union were largely confined to working and exhibiting within their own apartments, studios, and basements. These private spaces evolved into informal salons where small circles of friends and acquaintances gathered to view new work, drink late into the night, exchange ideas, recite poetry, perform music, and circulate illegal literature. In the absence of free speech and independent criticism, the kitchen table became both forum and lifeline. It was during one such evening in Oskar Rabin’s apartment, more than four decades after unofficial art had first been suppressed, that the idea emerged to finally bring underground art out of these enclosed interiors and into the open air.

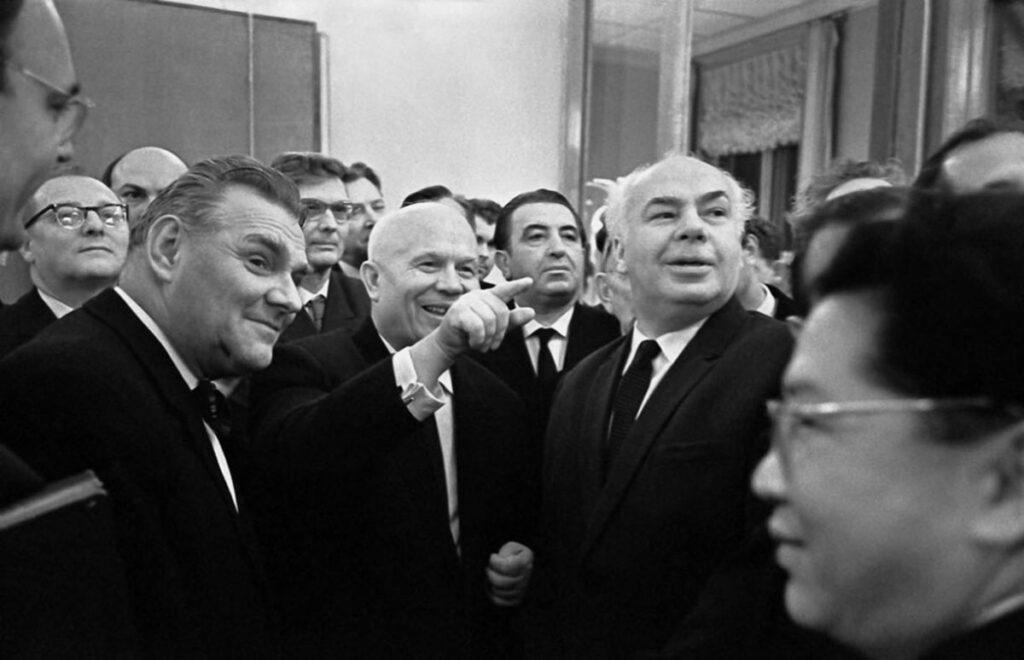

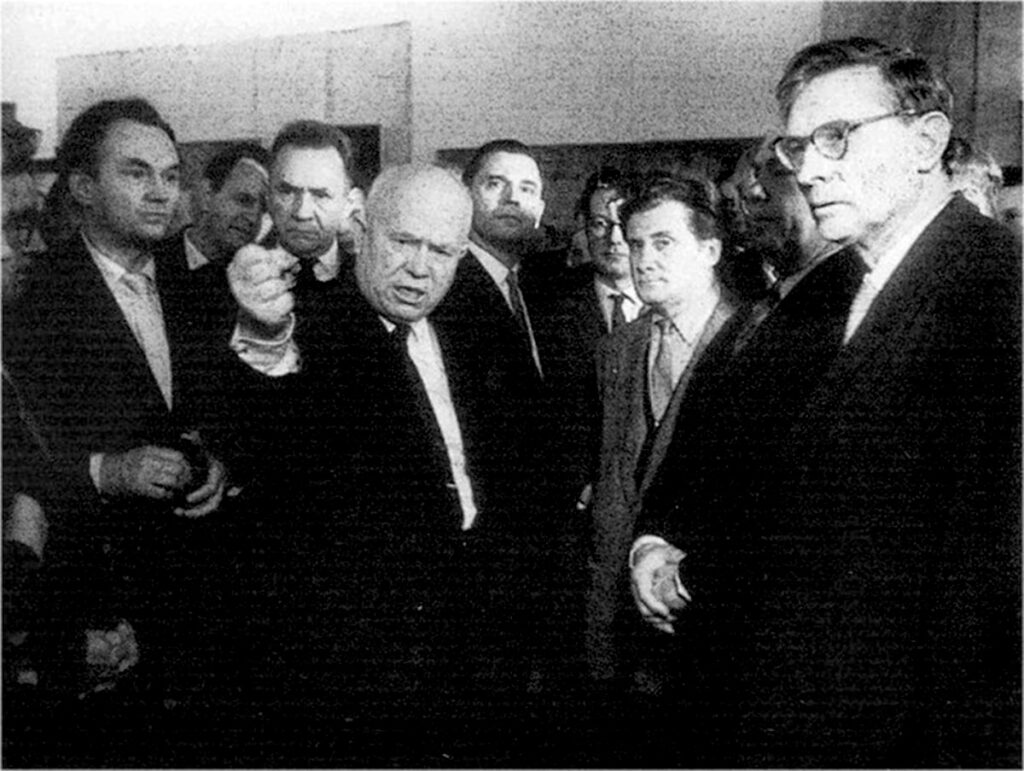

Several years earlier, during the early period of the Khrushchev “thaw,” state control over culture had briefly loosened. Artists working outside the strict confines of Socialist Realism cautiously began appearing in semi-public venues. This fragile tolerance collapsed in December 1962, when avant-garde artists exhibited work at Moscow’s Manege exhibition hall. That day, thirteen artists presented sixty works at the Manege at the special request of the Department of Culture of the Central Committee of the CPSU, marking the thirtieth anniversary of the Union of Artists.

Nikita Khrushchev visited the hall personally to inspect the exhibition, opening with characteristic irony: “Well, where are these sinners and righteous people of yours? Show them to me!” According to organizer Eliy Bielyutin, Khrushchev initially appeared quite calm, examining the works dismissively. Accompanying him was Mikhail Suslov, Secretary of Ideology, who dismissed the works as mere “daubs” depicting “freaks,” while Vladimir Serov, Secretary of the Union of Artists, cast doubt on whether the prices assigned to the works were justified, despite himself serving on the Union’s purchasing committee and helping determine those prices. “Is this painting? Just look at it, Nikita Sergeyevich, how smeared it is! Is it truly worth so much money?” he remarked.

Khrushchev and his entourage proceeded through the exhibition, the leader moving erratically from painting to painting, becoming steadily more unsettled until his attention settled on a portrait of a girl by Aleksey Rossal-Voronov. “What’s this? Why is one eye missing? She’s some kind of morphine addict!” he exclaimed. “Who gave them permission to paint like that? Send everyone to the logging camp, let them earn back the money the state spent on them! It’s a disgrace.”

Having lost his temper, he continued through the exhibition, branding other works “shit” or some analogous label and suggesting their creators be exiled beyond Moscow Oblast. Upon reaching Lucian Gribkov’s abstract work 1917, dedicated to the October Revolution, he demanded, “What a disgrace this is! What freaks! Where is the artist?” Gribkov stepped forward. “Do you remember your father?” Khrushchev asked. “Very poorly,” Gribkov replied. “Why?” “He was arrested in 1937 and I was very young.” After a pause, Khrushchev continued, “Well, fine, that’s not important, but how could you depict the revolution like that? What kind of thing is this? What, you can’t draw? Even my grandson draws better than you.”

He then confronted another painting, Leonid Mechnikov’s abstract depiction of Golgotha. Raising his voice again, Khrushchev shouted, “What is this? Are you men or goddamned faggots? How can you paint like this? Do you have any conscience? Who is the author?” Mechnikov, a retired navy captain, stepped forward calmly. Khrushchev again asked whether he knew his father, a question he was keen on posing to each artist. Mechnikov answered that he did. “And you respect him?” Khrushchev asked. “Of course.” Khrushchev then asked how his father could tolerate such painting. “He actually likes it,” Mechnikov replied, a response that reportedly left Khrushchev momentarily disarmed, his point deflated. Enraged, he literally spat on the painting and proceeded further.

After further attempts by artists to defend their work, the final straw came when Khrushchev approached Nikolai Krylov’s depiction of the Spassky Gate of the Kremlin. Bielyutin, exhausted after two sleepless days preparing the exhibition, attempted to explain the work’s deeper value, but it proved too little when Khrushchev’s attention shifted and caught Serov’s disapproving expression. Finally, Khrushchev burst out: “What are you talking about? What kind of Kremlin is this? This is a mockery. Where are the battlements on the walls, why can’t you see them? It’s too general and unclear. Look, Belyutin, I’m telling you this as Chairman of the Council of Ministers: the Soviet people don’t need any of this. You understand? I’m telling you this!”

Feeling uneasy, he turned again to Serov, now seemingly aware of his attempts to dissuade him from appreciating any of the art, “But you, Serov, can’t paint well either. I remember visiting the Dresden Gallery, they showed us paintings where the hands were painted so well you couldn’t see brushstrokes even with a magnifying glass. And you can’t do that either!”

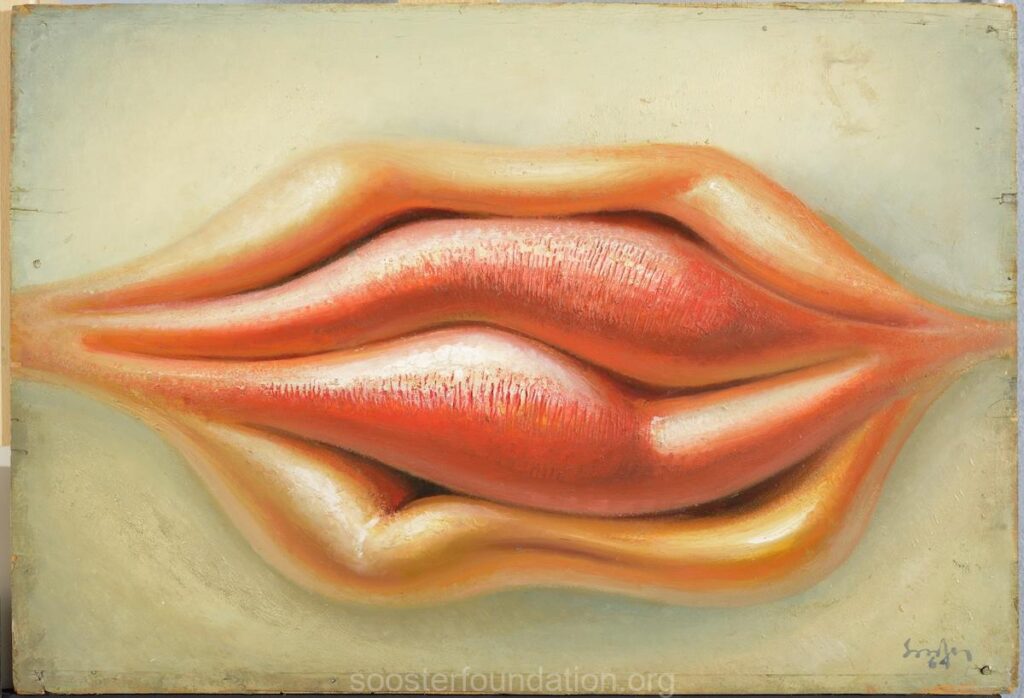

Another incident involved Estonian artist Ülo Sooster. Upon seeing Sooster’s painting of a landscape, Khrushchev asked him to explain what it depicted. “A lunar landscape,” Sooster answered. “And what, you’ve been there, asshole?” Khrushchev shouted. “That’s how I imagine it,” Sooster replied. Khrushchev continued raging: “I’ll send you to the West, formalist—no, I’ll deport you—no, I’ll send you to a camp!” To this, Sooster calmly responded, “I’ve already been there,” referring to the seven years he had spent in the Gulag after being deported along with many other Estonians by Stalin following World War II, an ordeal that cut short his studies at the Tartu Art College.

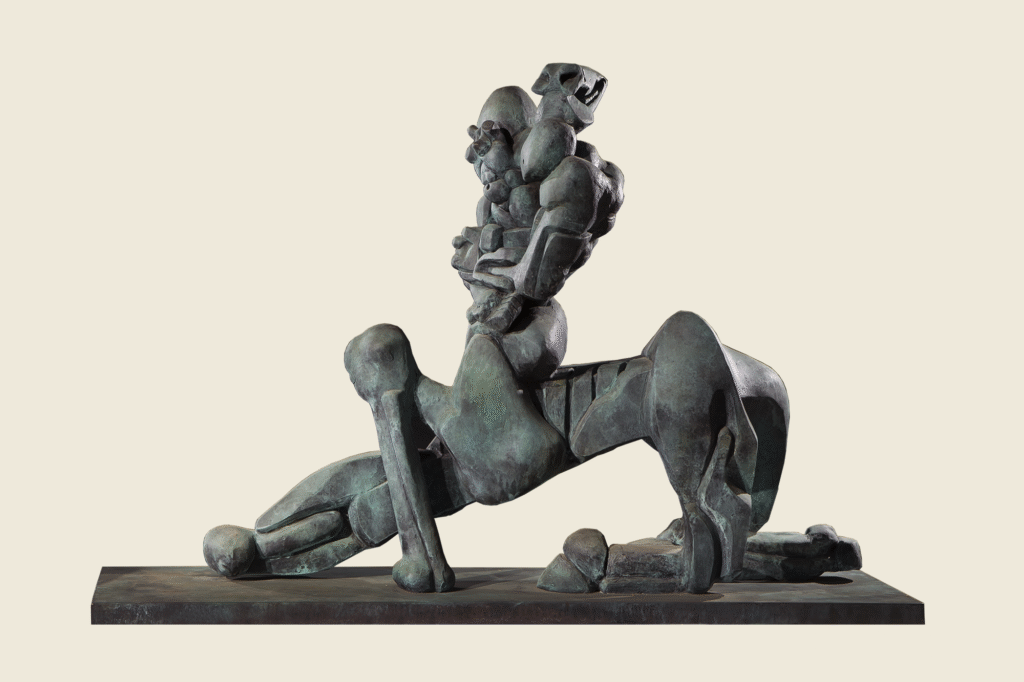

Another verbal exchange took place with the sculptor Ernst Neizvestny, whom Khrushchev accused of being homosexual. Neizvestny responded, “No, just give me a girl and I will show you,” a reply that, reportedly, Khrushchev found amusing.

After further arguments, including one between Suslov and Bielyutin over the accuracy of an artist’s depiction of a cement factory and its surroundings in the city of Volsk, Khrushchev and his entourage finally left the hall. As he descended the stairs, red-faced and waving his hands, he was heard declaring, “Ban it! Ban it all! Stop this disgrace! I order it! I say it! And keep an eye on everything! We must root out all supporters of this on the radio, television, and in the press!” His overall impression seemed to be that those involved in such art were a disgrace to their families, morally suspect, mentally unstable, or all of the above.

The exhibition was immediately closed, and the works were seized, with artists recovering them only many months later. Soon afterward, the same artists were reevaluated by the Moscow Union of Artists. Many lost their membership and, with it, their employment. Bielyutin was stripped of his teaching license and his right to publish scholarly work, leaving him without a job. Two days after the exhibition, police and plainclothes officers, likely KGB agents, visited his mother’s apartment, asking her to inform them where her son was employed and to present proof of employment to the housing office, a not-so-subtle signal that he should seek a new line of work.

These developments made it clear that any attempt to bring unofficial art into public view carried serious risk, a lesson that would resonate in the years leading up to the Bulldozer Exhibition. Still, Oskar Rabin and Aleksandr Glezer remained undeterred, determined to create opportunities for artists like themselves to exhibit beyond the confines of private apartments and basements.

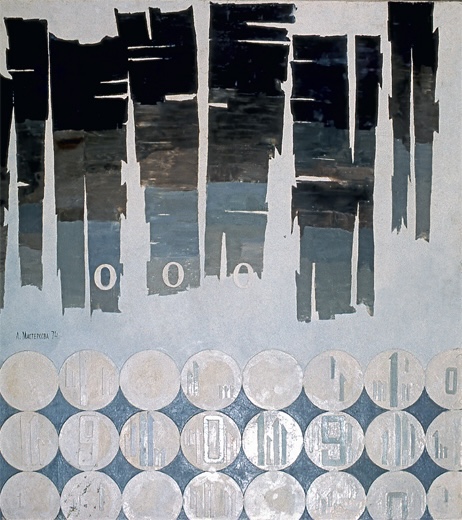

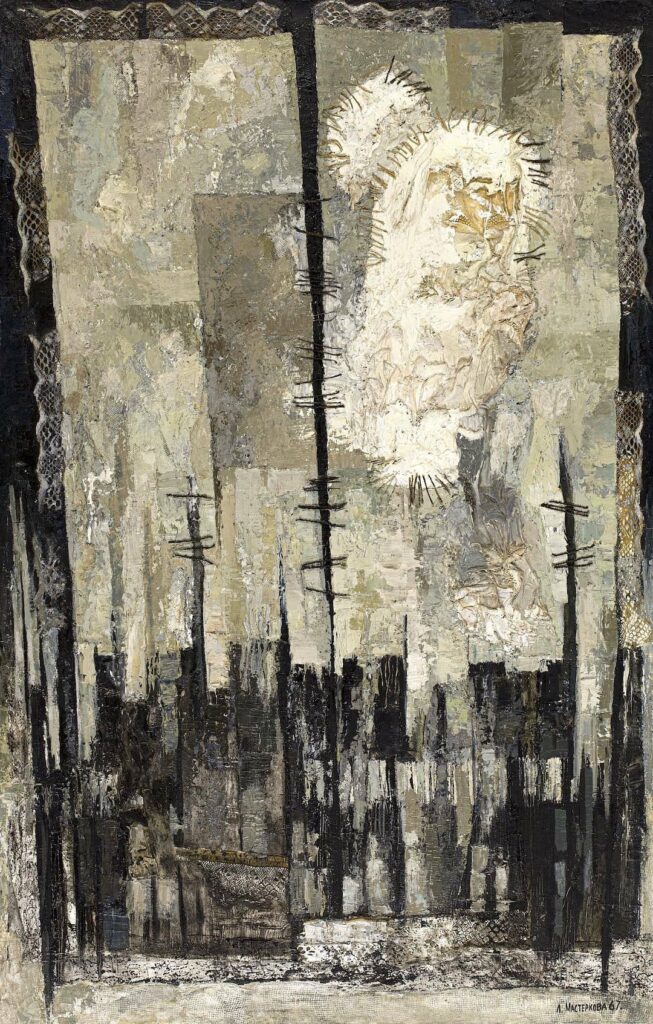

Years before the outdoor exhibition that would achieve worldwide notoriety, their first attempt came on January 22, 1967, when Rabin, Glezer, and about a dozen other artists organized an exhibition at a community center at the eastern edge of Moscow. Featuring works by Vladimir Nemukhin, Lidiya Masterkova, Dmitriy Plavinsky, Anatoliy Zverev, Nikolai Vechtomov, Valentin Vorobyov, and others, as well as Rabin himself. The event attracted distinguished guests such as poets Boris Slutsky and Yevgeny Yevtushenko. The belief was that the Soviet state, now with Brezhnev at the helm, may react less harshly to the gathering. Nevertheless, authorities from the city committee shut the exhibition down after barely two hours, declaring it ideologically unacceptable, even though roughly two thousand visitors had already managed to see the works.

On March 10, 1969, another exhibition featuring many of the same artists took place in the conference hall of the Institute of International Economics and International Relations. Earlier that very day, authorities had already closed an exhibition of works by Nemukhin and Rabin organized by Glezer in Tbilisi.

By 1969, the Moscow City Committee of the Communist Party had apparently had enough. Feeling that it was facing off against a hydra, the Committee ruled that all exhibitions now required approval from the Moscow Union of Artists. The cultural climate toward informal artists had worsened considerably in the seven years since Khrushchev’s Manege visit.

In response, unofficial artists increasingly searched for ways to show their work outside state-controlled institutions. Apartment exhibitions or concerts, so-called kvartirniki, had become common, but these remained private, semi-secret events limited to small circles, and still liable to be shut down by the authorities if any neighbors were to complain. That was exactly the case when an apartment art exhibition held by artists Vitaly Komar and Aleksandr Melamid was shut down by police and all attendees were subjected to a humiliating interrogation. “So, what did you think of the Jewish pictures?” one of the police sergeants was noted asking the attendees with a chuckle, referring to the ethnic background of the artists. “If you come across us again, you’ll lose your job!”

As a result of these frustrating incidents, idea gradually emerged: if official halls were closed to them, and so were private homes, why not exhibit outdoors, in open public space? Rabin, widely regarded as the de facto leader of Moscow’s nonconformist artists, formally proposed the alternative: an informal outdoor exhibition for artists unaffiliated with official creative unions. For artists systematically excluded from institutional spaces, this was less an act of provocation than one of necessity. Additionally, both he and Glezer wanted to use this exhibition to reach a broader audience, not just those few in the know. Still, several more years would pass before the plan could finally be put into action.

At the same time, Moscow was rapidly expanding, with large new residential districts appearing on the city’s outskirts. These areas often contained undeveloped plots and vacant lots, spaces technically public yet lacking clear oversight. Such locations seemed ideal: accessible enough for visitors, but far enough from the city center to avoid immediate intervention. Plans for an outdoor exhibition slowly took shape, though organizers remained aware that authorities could intervene at any moment.

The original choice of a vacant lot as the exhibition site is often attributed to fellow artist Vitaly Komar. “I remember we were sitting at Rabin’s after the police broke up our apartment exhibition, and I told Oskar that I had read in some magazine, I think it was the magazine ‘Poland,’ that Polish artists regularly hold exhibitions in parks,” he recalls. The idea offered both a practical solution to the absence of sanctioned venues and a symbolic challenge to the system that excluded them.

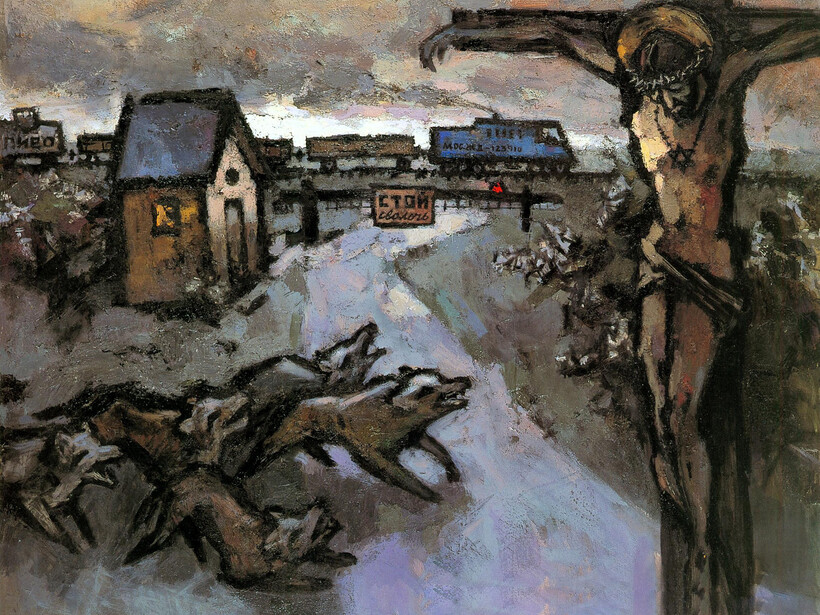

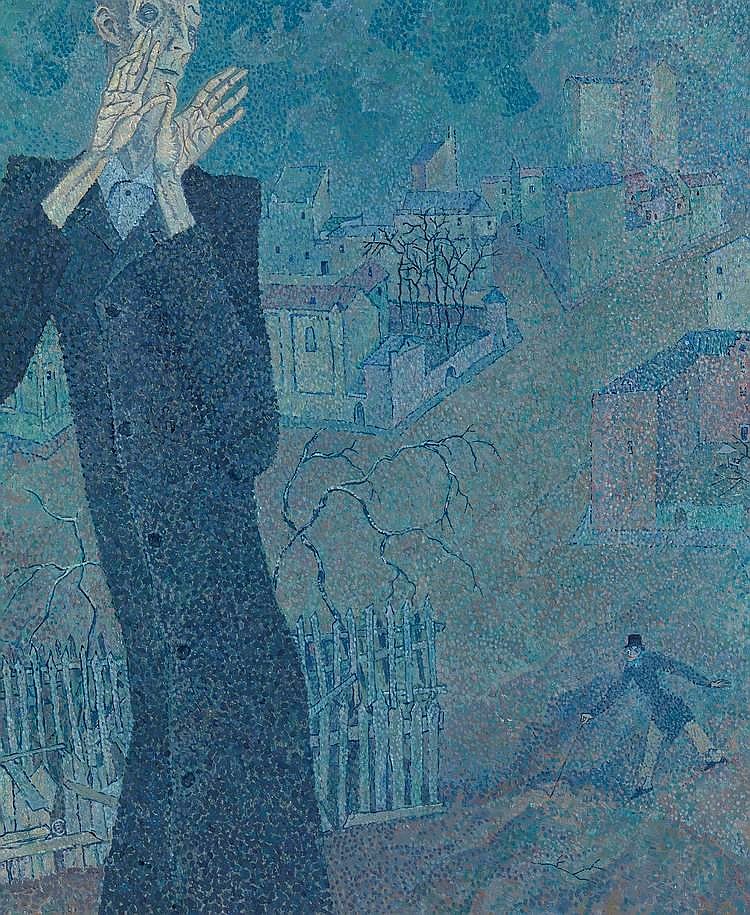

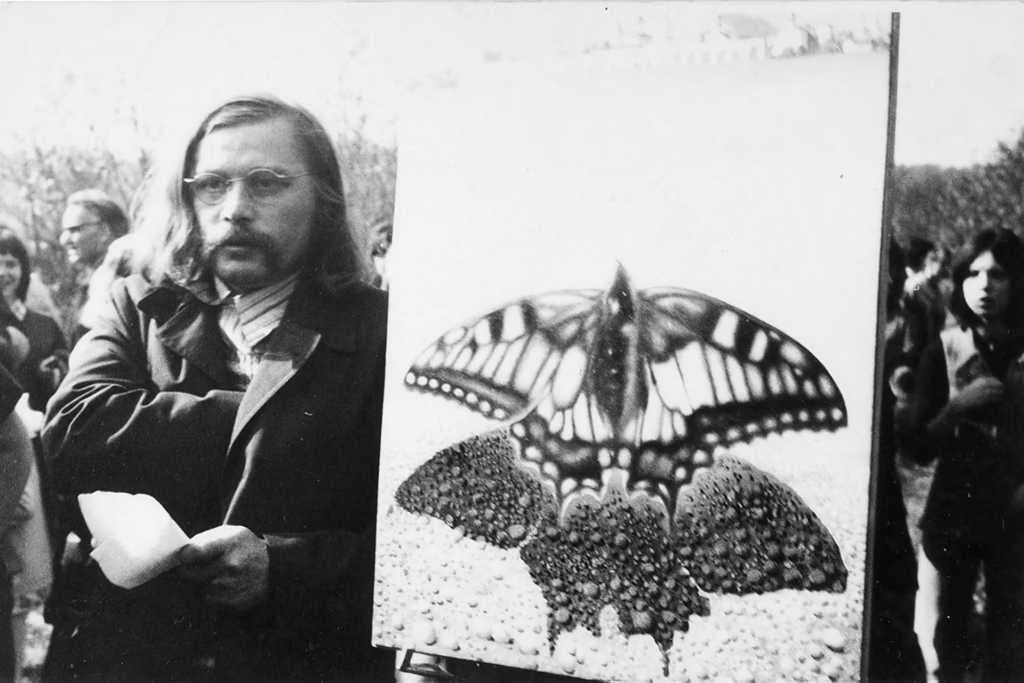

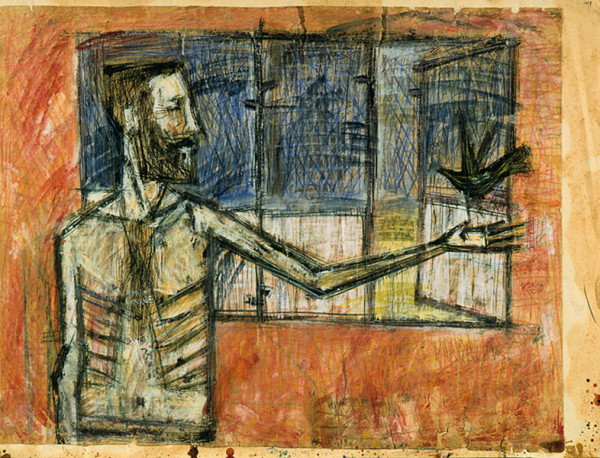

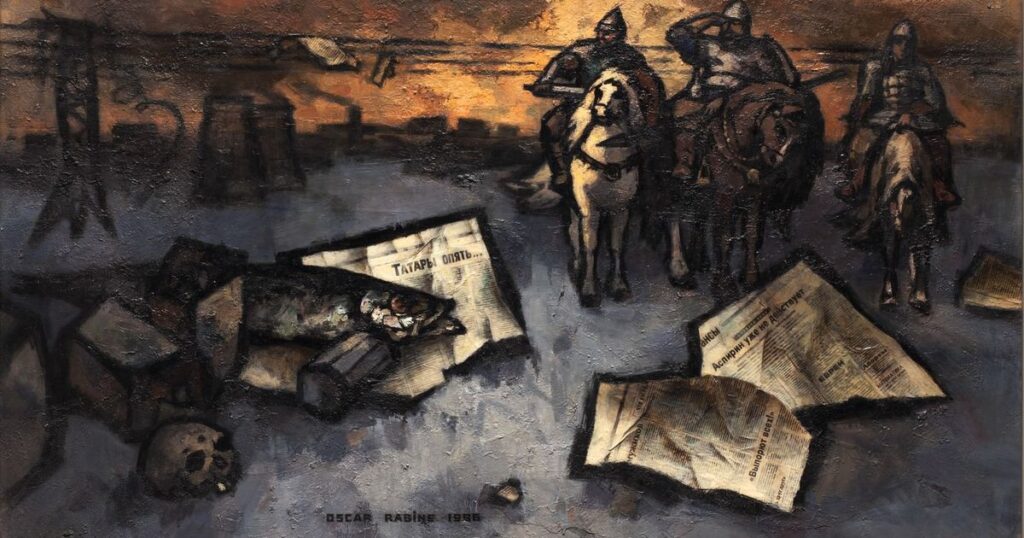

Rabin himself was known for bleak still lifes and landscapes rendered in an expressionistic manner, with many of his most recognizable works depicting the peripheral districts of Moscow, often villages and military barracks.

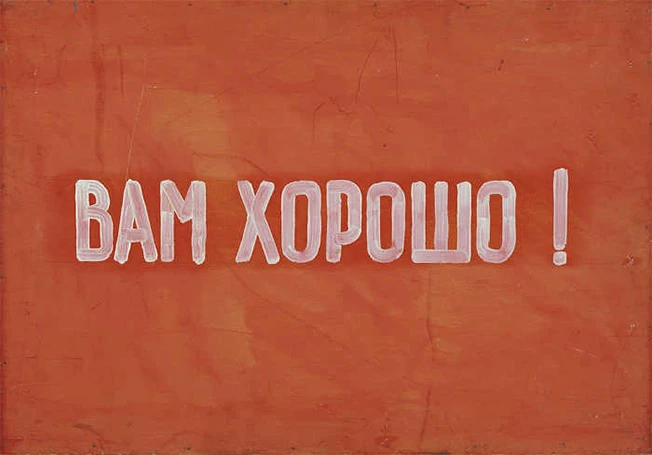

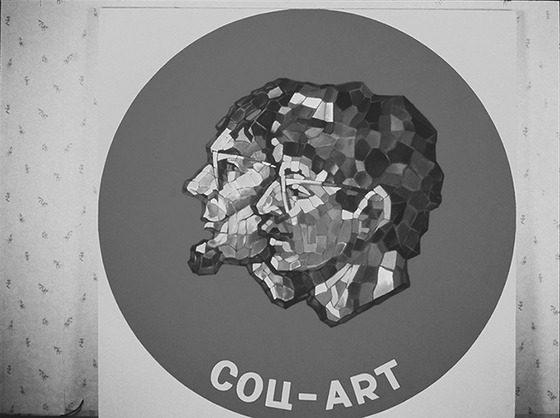

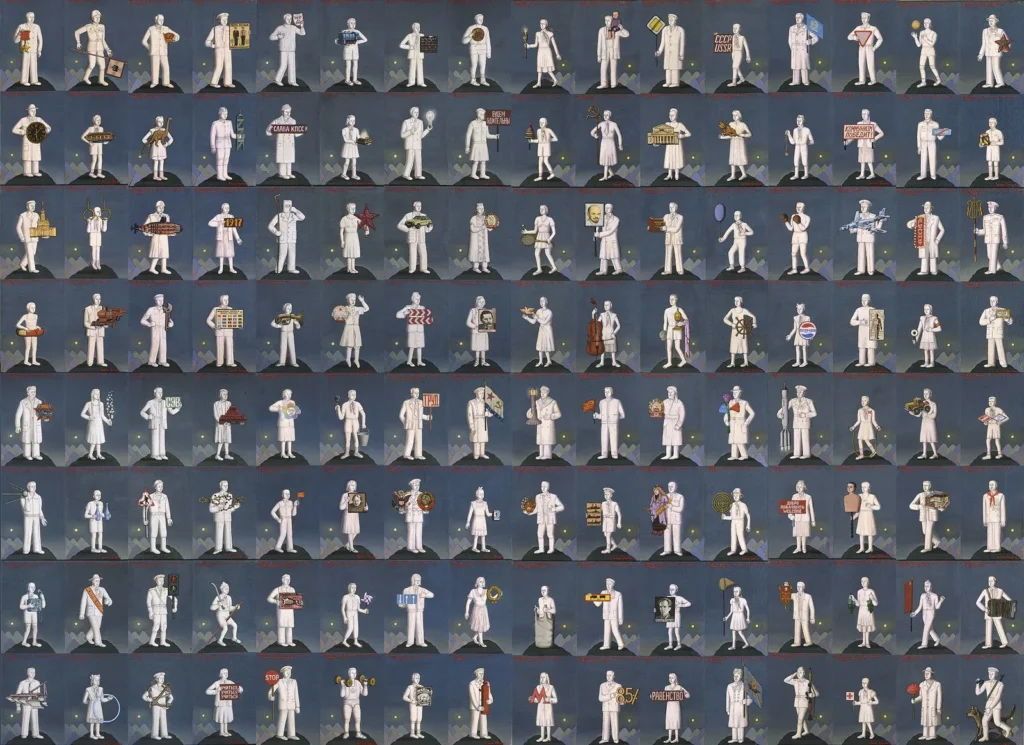

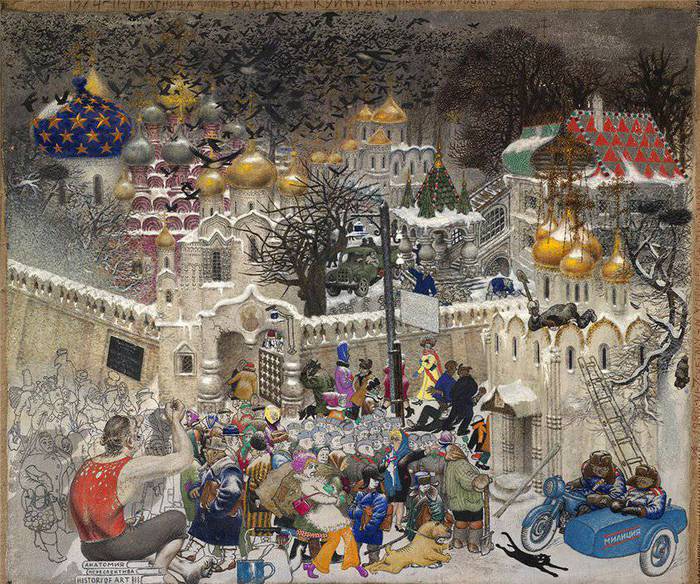

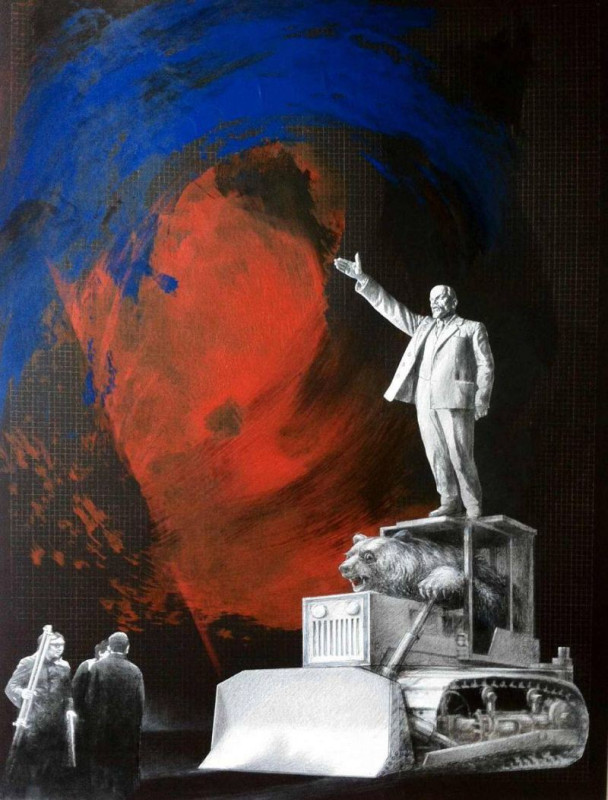

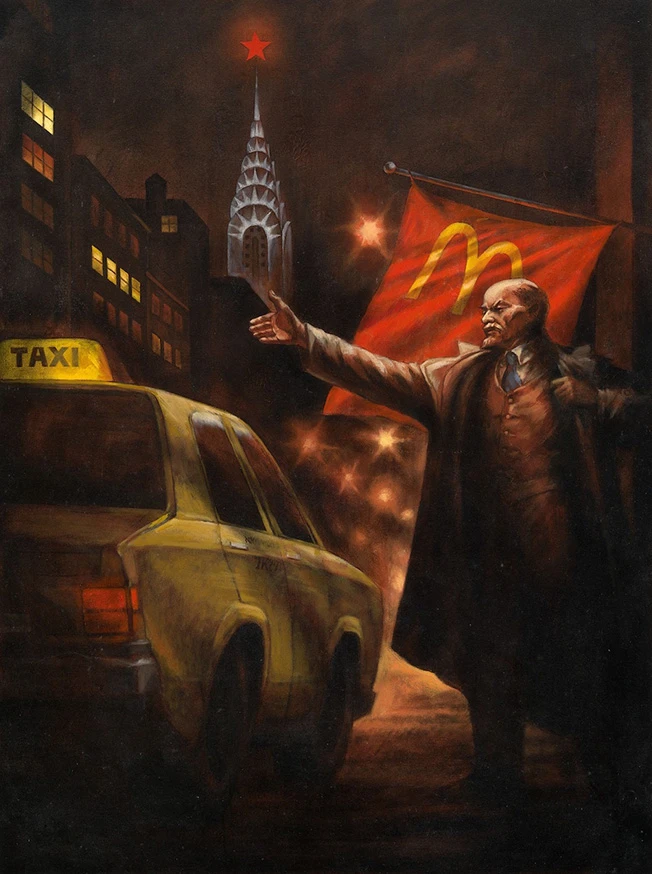

By contrast, Vitaly Komar worked in partnership with Alexander Melamid, the pair approaching dissent through irony and parody. They mocked the visual language of monumental Soviet art, its stock imagery, and its cult of leadership. In this sense, their work paralleled that of American Pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Ed Ruscha, who similarly dismantled symbols of power, albeit those of capitalism rather than the socialist state.

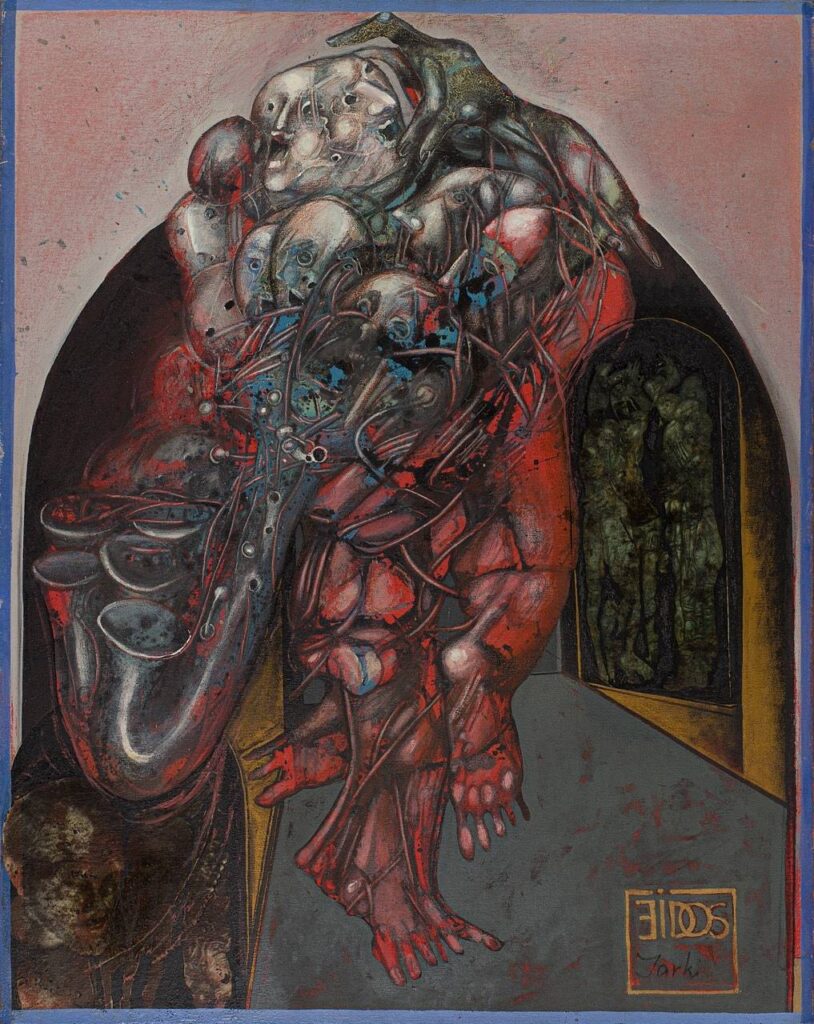

Initially, the organizers intended to approach the established and prominent names of the underground art scene, including those respected few who were present at the Manege Exhibition in 1962. Ernst Neizvestny, Lev Kropivnitskiy, Ilya Kabakov, Lev Nussberg, and others, considered the older generation of artists, were approached. All declined, shying away from what they saw as a reckless proposal from a group of young adventurers. Even younger artists Oleg Tselkov and Boris Sveshnikov, already legends in in their own right, turned down the invite.

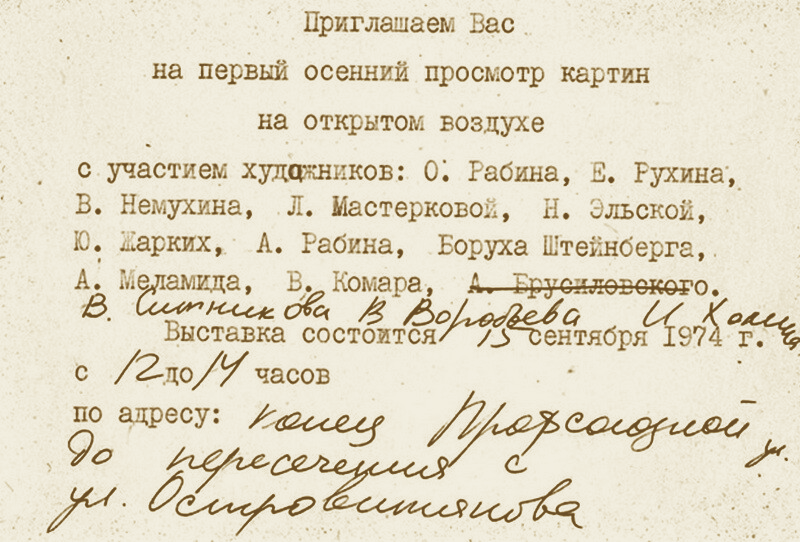

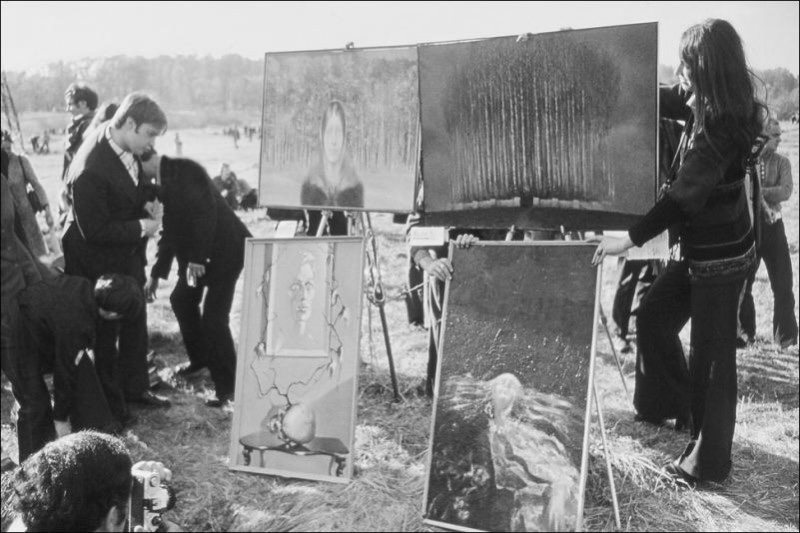

By 1974, additional artists, now from the younger generations, lent their support to the idea, and the group came to include Evgeniy Rukhin, Vladimir Nemukhin, Lyudmila Masterkova, Nadezhda Elskaya, Yuri Zharkikh, Valentin Vorobyov, and others. A vacant field was located in Belyayevo, a residential suburb on the outskirts of Moscow. The site was chosen carefully: distant enough from KGB offices to delay an immediate response, yet close enough to a metro station for visitors to reach it easily. Without access to galleries or proper equipment, the artists assembled makeshift display stands from whatever wood they could find. The final date of the exhibition was set to be September 15, 1974, a Sunday.

That same year, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR decreed that the internationally renowned dissident writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn be stripped of his Soviet citizenship and deported to the West, effective immediately. In response, Oskar Rabin grimly remarked, “Now their hands are free to go after us.”

Seeking to remain within a narrow legal gray zone, the organizers notified the Moscow City Council two weeks in advance of their intention to hold an open air exhibition and asked to be informed of any objections. At the authorities’ request, works were submitted for inspection by Communist Party officials and the organizers were summoned. Awaiting a final answer, the organizers gathered at the Rabin family home and anxiously awaited a response from the Council’s official courier.

Valentin Vorobyov described the scene: “In the small apartment, painted a brown, barrack-like color, there hung a carved icon with a smoky oil lamp. The corpulent Nemukhin dozed on the tattered sofa, occasionally opening his eyelids. [Oskar Rabin] stood vigil by the telephone, his shaved head bowed. The underground’s newcomers–Elskaya, Tupitsyn, Komar, and Melamid—puffed incessantly on stinking cigarettes and rushed down the narrow corridor in a crowd when the doorbell rang.”

Finally, a response came. A City Council representative reportedly told them the lot was available and that the exhibition would be neither officially supported nor explicitly prohibited, though they were urged not to proceed. The artists recognized the ambiguity as a prelude to possible provocation, yet remained undeterred.

As September 15, 1974 approached, the list of participants shifted repeatedly. Some artists withdrew shortly before the exhibition out of fear of reprisals, including Vasily Sitnikov, Boris (Borukh) Shteinberg, and Anatoly Brusilovsky, the latter replaced by poet Igor Kholin. The consequences were real: many feared conviction for anti Soviet activity, loss of livelihood, or even confinement in psychiatric hospitals for indefinite periods, a common practice for those deemed dissidents or threats to the state.

Roughly twenty-four artists ultimately arrived, fully aware the event might be shut down by any means necessary. Preparations took on the character of a covert operation. Paintings were gathered the night before at the apartment of mathematician and fellow traveler Viktor Tupitsyn, located near the exhibition site. Despite living on the outskirts, Tupitsyn welcomed the opportunity to help make the exhibition possible near his home: “We chose such an unattractive location as a vacant lot for a simple reason: displaying paintings on a square, street, or embankment could easily be considered a violation of public order under Soviet law.”

By contrast, a vacant lot seemed to offer at least a fragile legal buffer, which some hoped would avoid drawing state attention. Some artists stayed overnight at Tupitsyn’s home. If anything suspicious occurred at the site, they planned to alert another group traveling separately by metro. They saw only idle construction equipment, seemingly nothing out of the ordinary.

However, the authorities were much more aware than many assumed. The day before the event, Brusilovsky, who previously declined to participate and himself still a member of the Union of Artists in good standing, phoned the group, relaying a simple message to any other Union members thinking of participating: “Comrade Dudnik [head of the Moscow Union of Artists] does not recommend his members exhibit on the vacant lot.”

On the morning of the exhibition, believing the coast was clear, participants and visitors traveled to Belyayevo in small groups by metro, agreeing not to intervene if anyone was detained en route so that at least some would reach the site. Rabin himself was briefly detained on suspicion of stealing a watch, followed by his friend and collector Aleksandr Glezer, who tried to intervene and was detained as well. Both were soon released, the incident officially dismissed as a mistake, with police claiming the real thieves had just been apprehended.

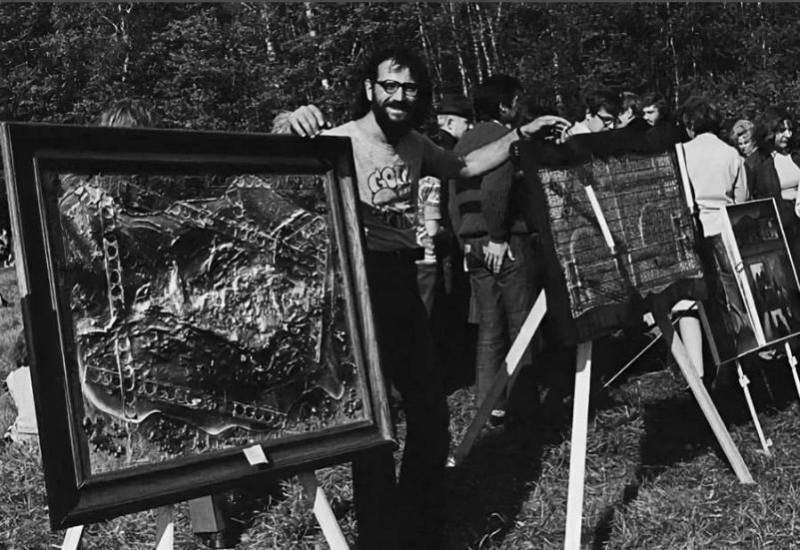

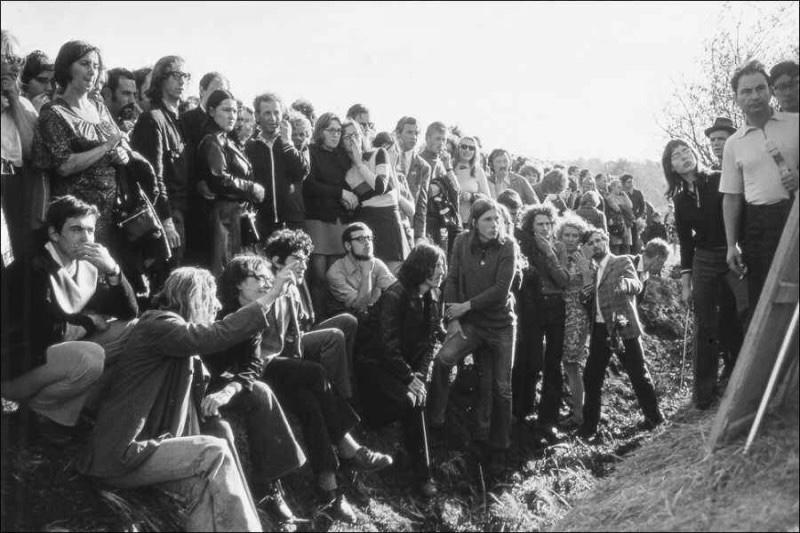

The weather remained overcast, and the previous night’s rain added logistical difficulties. Nevertheless, by noon a substantial crowd appeared, ready and willing to wade through the mud to reach the exhibition. Roughly two dozen artists, some traveling from Leningrad, Pskov, and Vladimir, came to show their work. Several had already exhibited internationally in New York, San Francisco, London, Paris, and Rome, yet within the Soviet Union they still remained barred from formal exhibitions and denied membership in the Union of Artists.

Alongside friends and relatives were correspondents from Western media and members of the diplomatic corps who had gotten wind of the event in advance, purposely invited by Glezer as an additional cover for the safety of the exhibition’s participants. Diplomats in attendance included those from the United States, Western Europe, Asia, and Latin America.

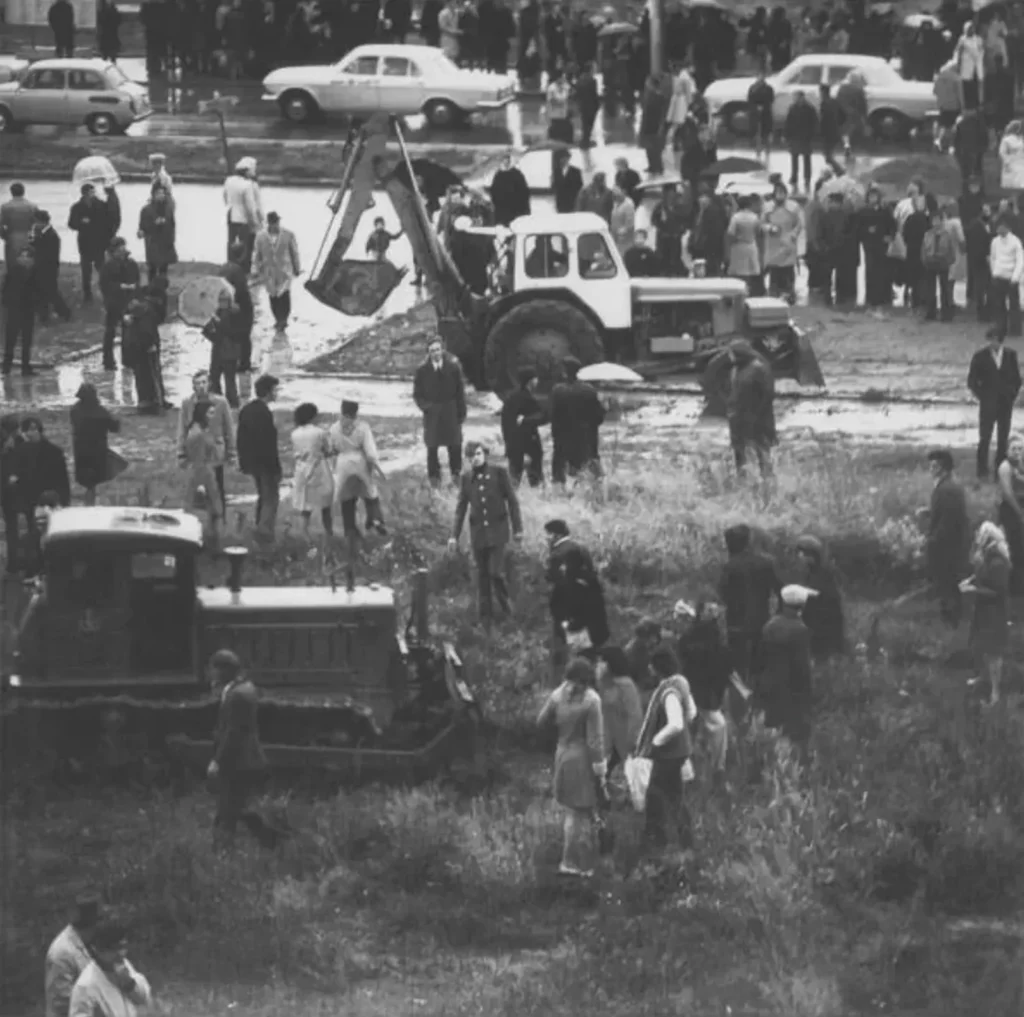

The exhibition was intended to last only two hours, but moments after it began, plainclothes civilians approached, identifying themselves as landscapers. They announced a tree planting operation was scheduled for that exact time and place, requiring cleanup of the entire field, and accused the artists of interfering with their work. Behind the men were the very same heavy machinery and trucks loaded with saplings seen the night before, with bulldozers brought in order to “level the ground”.

Valentin Vorobyov later recalled the scene before them: “It rained all night, and our vacant lot had turned into a muddy puddle. A blackened fire smoldered on a hill. A pair of dump trucks with green saplings onboard, a flimsy dredger, and the dark silhouette of a bulldozer were visible in the thick fog. Surrounding the heavy equipment, bristling with shovels, pitchforks, and rakes, stood a formidable enemy–the excavators and planters of great power. There was nowhere to retreat. Behind us, the lucrative diplomatic corps and the coveted television were gathering, and in front stood the armed Russian people. My neighbors on the right flank, Komar and Melamid, and I, with our paintings at the ready, advanced on the enemy.”

The gathered men also displayed a large red banner reading “Everyone to the Saturday Cleanup!” even though it was Sunday. According to them, this was a planned community cleanup day. Some believe the banner very well might have belonged to such an event until the authorities took full control of it to use as a cover for their intervention, explaining the mismatched days.

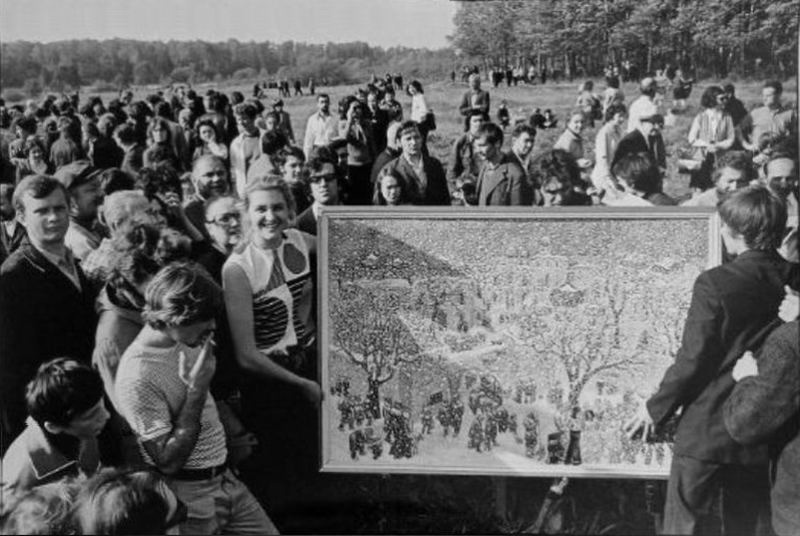

What followed was similarly described by Aleksandr Glezer as “a surreal spectacle.” Some artists had not even uncovered their canvases when tensions escalated and physical confrontation began. Artists and visitors alike were assaulted, paintings ripped from hands and trampled, with what was left of the canvases being thrown into dump trucks that immediately drove away. Like tanks advancing on enemy combatants, three bulldozers moved slowly across the lot to crush whatever art remained as spectators and press watched in disbelief from across the street. At this point, Glezer and some other artists pushed through the crowds to try to retrieve the paintings before they were crushed.

Oskar Rabin reached the paintings and attempted to pick them up and display them to the crowd, but this did not deter the bulldozer operators, who swiftly drove over several of the artworks. Attempting to halt their advance, Rabin used his own body to shield the paintings, only to be caught and dragged several feet while hanging from a bulldozer blade, bending his legs to avoid them being crushed. His 22-year-old son Aleksandr, also an artist, ran to his aid. By this point, one of several uniformed policemen, who stood by the sidelines without reacting, finally stepped in and ordered the bulldozer to stop, at which point the father and son were thrown into a police car and driven away.

Meanwhile, others attempted to save their works as the so called vigilantes charged the crowd with pitchforks and shovels, attacking any artists they could catch, including Yevgeny Rukhin and Valentin Vorobyov. Another artist, Nadezhda Elskaya, attempted to climb a large pipe to display her paintings from above but was pulled down by the attacking men and also arrested. “They arrested the participants of the exhibition before my eyes,” recalled Viktor Tupitsyn. “When Yuri Zharkikh was taken away, I grabbed his painting and started showing it to the audience. Clutching it to my chest, I caught myself thinking I was doing it out of solidarity, even though aesthetically I had nothing in common with Zharkikh.”

Vorobyov recalls the destruction of the art: “One ferocious warrior rammed a shovel into my defenseless painting and threw it in disgust into the mud, like St. George the Victorious throwing a snake under the floorboards … Floundering in a vile puddle, I saw out of the corner of my eye Masterkova’s magnificent painting hurled into the back of a dump truck, where it was immediately trampled like a pile of manure. The enemy broke up a large plywood panel by Komar and Melamid depicting the dog Laika and Solzhenitsyn into firewood and treacherously tossed it into the fire.”

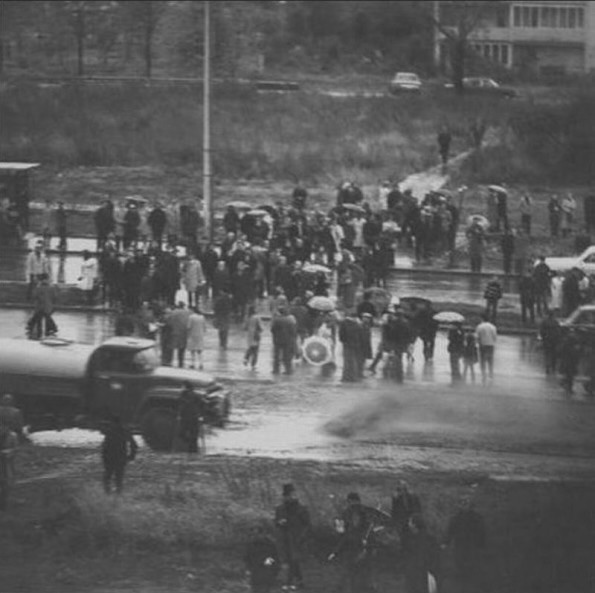

Many spectators for trying to prevent the artists from being assaulted, were themselves harshly beaten and detained as well. Diplomats and foreign correspondents, some prepared to purchase uncensored Soviet art, were treated with particular brutality. As one witness later recalled, while artists were accustomed to arbitrary treatment by authorities, the assault on foreign journalists crossed a visible line.

Water tankers normally used for street cleaning, now fitted with high pressure hoses, were brought in to disperse the remaining crowd and destroy surviving artworks by blasting them with cold, dirty water. Throughout the event there was a steady downpour of rain, which meant the street cleaners were truly only there for one reason. One truck even drove over a curb and attempted to chase down a group of people. At that moment, New York Times correspondent Christopher Wren attempted to photograph the scene. The attackers now directed their attention to the journalists, smashing Wren’s camera into his face while others held him down and beat him, breaking his arms.

Two more American correspondents, Lynne Olson of the Associated Press and Michael Parks of the Baltimore Sun, who attempted to shout at the men to stop the violence, were both struck in the stomach as well. ABC journalist Russell Jones was also manhandled but escaped more serious injury. Several uniformed policemen, witnessing the violence, still made no attempt to intervene. As a result, the journalists bore the brunt of the direct violence and needed medical treatment. Wren later required dental treatment in Finland after a tooth was chipped when his camera was smashed into his face. One of the few surviving rolls of film were taken by Vladimir Sychev, who passed his on to a friend before he was taken away by authorities.

After the remaining crowd either fled or was arrested, the attackers got into their trucks and swiftly drove away, having burned at least three paintings in their bonfire in what appeared to be a final gesture of domination. Confiscated works that escaped this fate were driven away to an unknown location, with only a select few successfully rescued by their creators. Notably, the dump trucks used to haul away the artwork were loaded with the same soil and saplings ostensibly intended for planting that day, the very issue over which the initial dispute had begun.

“No one expected such a brutal reprisal,” recalled artist Sergei Borodachev, who managed to save one painting. Though modest in scale, the exhibition was treated by authorities as a serious threat. They mobilized an overwhelming force that included bulldozers, as many as 20, according to Borodachev, several water cannons and dump trucks, and hundreds of both off-duty and uniformed police. Officially, those involved were interchangeably described as “landscapers” “civilians” or “vigilantes”, supposedly acting out of spontaneous outrage at an affront to proletarian values. It was never denied, however, that this was an operation that was directed by the KGB.

One of the figures overseeing the operation presenting himself as an official from the executive committee of Moscow’s southwestern district, claimed the exhibition was being dismantled because local workers had volunteered their Sunday to transform the vacant lot into a “park of culture.” and extend the forest through the planting of trees. When pressed by New York Times reporter Christopher Wren, he gave his name as “Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov”, the Russian equivalent of Joe John Johnson. The explanation rang hollow. If a cleanup day had truly been planned in Belyaevo, notices would have appeared in nearby courtyards, organizers would have been mobilized, and large numbers of local residents assembled. The only evidence of any cleanup day, was a letter published in a newspaper calling for a community cleanup for the day before. Moreover, such cleanup days were not held during the rainy autumn season, even if tree planting sometimes was.

All in all, eyewitnesses later emphasized how quickly the events unfolded. From the moment the canvases were unpacked to the complete destruction of the exhibition, only about twenty minutes passed. During that brief span, it is estimated that between 300 and 700 people were present, with the most confident press accounts placing attendance at around 500. Vitaly Komar, later described the scene as a turning point in his life:

“When I saw the bulldozers, my last illusions about the rule of law in the Soviet Union vanished. As if in a dream, I watched the civilians destroying our works, beating and arresting those who resisted them. I was petrified. But when they pushed me into the autumn mud and began to tear my ‘Double Self-Portrait with Melamid as Lenin and Stalin’ from my hands, the fear vanished. They had already defaced several works of our Sots Art, but this ‘Self-Portrait’ was especially close to me. At that moment, when one of them stepped on the hardboard and was about to break it, I imagined myself not as Lenin or Stalin, but as Tolstoy or Gandhi. I raised my head and quietly, with a confidential intonation, said: ‘What are you talking about? This is a masterpiece!’ ”

Our eyes met, and some inexplicably “different” connection arose between us. Perhaps the word “masterpiece” recalled something long forgotten? I don’t know, but he didn’t destroy this work; he simply tossed it into the back of a truck. A minute later, still lying in the mud, I watched the garbage truck disappear into history and smiled. Maybe this was my “finest hour”? Maybe every artist secretly dreams of their work being destroyed by the viewer?”

According to Oskar Rabin, the most active participants were taken to the police station. Rabin himself and Vladimir Nemukhin were fined 20 rubles, a sum that is roughly equivalent to $178 today, in addition to being detained. Younger participants, including Aleksandr Rabin, Nadezhda Elskaya, and photographer Vladimir Sychev, were simply sentenced to fifteen days’ detention on the same charges.

Viktor Tupitsyn described the scene: “Leaving the vacant lot, I was amazed at the skill of my captors. Thin and short, they toyed with me like badminton until they forced me into a car, a Moskvich or a Zaporozhets, with two other officers. On the way to the police station, they forced me between the front and back seats and began beating me with a peculiar gusto. Since the car was small, my opponents mostly interfered with each other. The blows came simultaneously, from all sides, and their effectiveness left much to be desired. At the police station, the participants and organizers of the exhibition were placed in a common room. They interrogated us one by one, but only formally—date of birth, home address, place of work, and so on. Each was fined for disturbing the peace and released that evening.”

Many witnesses were detained as well, eventually being let go without being charged with any crimes. Aleksei Tyapushkin, a decorated World War II veteran, member of the official Union of Artists, and non-participating spectator of the events, was among those detained. When he inquired as to the fate of the confiscated paintings, he was informed that they were all burned. One of the policemen receiving the detainees at the station, later identified as a lieutenant of the militia Avdeyenko, reportedly said “You should all be shot! Only you’re not worth the bullets.”

Interestingly, one final detail further underscores the orchestrated nature of the operation. Viktor Tupitsyn, who was also briefly detained, reported seeing an internal order at the police station instructing all department employees to report to the vacant lot the following day in civilian clothes. He also observed individuals entering the station in plain clothes and later returning to their offices in uniform.

In the aftermath, many logically asked whom the artists gathered in a muddy vacant lot on the outskirts of Moscow were truly threatening. The most likely answer lay in the Soviet government’s fear that the public would sympathize with and identify themselves with any group outside of the control of the state, artists or otherwise.

Shortly after the exhibition, Viktor and Margarita Tupitsyn were picked up by a black Volga and taken to a place where they were showed a propaganda film about the exhibition. After the screening, they were asked to “write a retraction for the newspaper and declare that this whole mess was the work of hooligans and outcasts, and that the authorities had behaved correctly and tolerantly.” Viktor declined, offering no cooperation.

The authorities subsequently set in motion a counter narrative aimed at suppressing any sympathy for the victims of the operation. Five days after the incident, a carefully staged letter appeared in the arts newspaper Sovetskaya Kultura (Soviet Culture), ostensibly written by four local participants in a Voskresnik, or voluntary civic cleanup day. The signatories, identified as V. Fedoseyev, a lathe operator and “communist labor shock worker,” E. Svistunov, a radio fitter with the same designation, V. Polovinka, head of the local road and improvement department and a district council member, and B. Timashev, an electrician, complained that their efforts to beautify the neighborhood had been disrupted.

The letter described the arrival of the artists in deliberately disingenuous and pejorative terms: “Imagine our bewilderment, and then our indignation, when, around midday, at the intersection of Profsoyuznaya and Ostrovityanova Streets, cars suddenly began stopping one after another, from which some cheeky, sloppily dressed people began pulling out very strange colored canvases, both framed and unframed, with the intention of exhibiting these paintings right there, in the open air, right where people were working at that hour. With their arrival, the work rhythm of the voskresnik was disrupted. At the quiet intersection, a crush, noise, and hubbub began; uninvited guests behaved provocatively, snatched shovels and rakes from people working, pushed them, trying to chase them away from the lawns, tore down a poster calling for participation in the clean-up day, obstructed traffic, cursed and swore.”

The letter continues by morally condemning the artists and denigrating the quality of their work: “We, residents of Cheryomushki, who witnessed this outrage, categorically protest against such ‘artistic’ actions and demand that the laws of our country and public order in the capital be respected by both so-called free artists, who apparently have no understanding of true art, and their foreign friends and patrons.” The message was clear: the violence in Belyaevo was to be reframed not as repression but as a justified defense of civic order and cultural norms.

Clearly, the reality situation was very different, but since all press was state controlled, no artist had the opportunity to formally respond with their side of the story. Yet since the violence of that day extended even to diplomats and journalists in attendance, that is people who still had a voice, it made an international incident almost inevitable. Very little visual documentation of the event survived, due to the fact the authorities went out of their way to ensure cameras were confiscated and film torn out and deliberately exposed to light.

Nevertheless, a handful of images reached the international press. The following day, still recovering from his injuries, Wren wired his article “Russian Disrupt Modern Art Show” back to the New York Times and it was published the same day. Alongside other coverage and formal complaints filed by press organizations regarding the treatment of their journalists, the report triggered a major scandal abroad.

As art historian and exhibition participant Margarita Masterkova-Tupitsyna later observed, foreign involvement proved decisive. According to her, the intense international press coverage made it impossible for the authorities to dismiss the artists as marginal figures producing meaningless amateur work, where once they were easily collectively written off as alcoholics or mentally unstable individuals. From the late 1950s onward, unofficial Soviet art had benefited from consistent interest and protection from diplomats and Western journalists, and this time was no exception. Their presence forced Soviet leaders to respond cautiously and limited how far repression could go. Without such external attention, it is suspected unofficial art might not have survived, let alone developed, during those years.

Art historian Yekaterina Andreyeva suggests that the security services realized they had gone too far, compelling a Soviet state mindful of its global standing to engage in damage control in the months and even years that followed. Art critic Sasha Obukhova has expressed a similar view, linking this overreach to the subsequent, and otherwise unlikely, softening of official attitudes toward nonconformist artists. Western journalists were united in condemning the authorities’ actions and pressed senior officials to respond publicly and reconsider their approach to suppressing unofficial art.

In the immediate hours and days after the exhibition, overwhelming media and political attention quickly altered the outcome. Elskaya was released the evening of her arrest, while Oskar and Aleksandr Rabin along with Sychev served only three days of their sentences following a hunger strike and significant international outcry. None of the arrested artists were ultimately required to pay their fines.

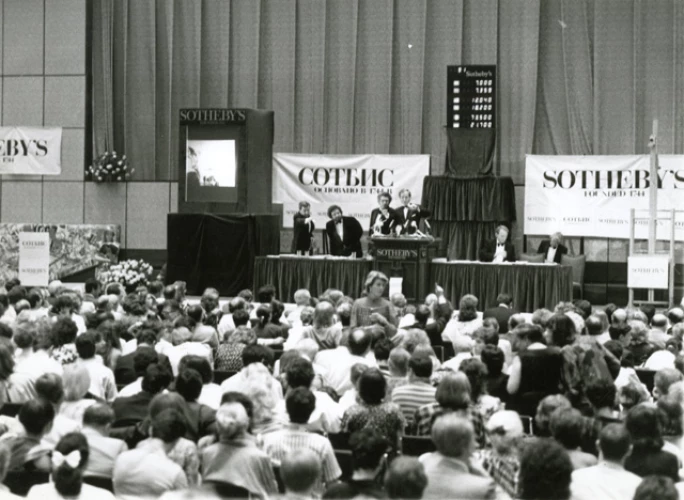

More than a decade later, at the end of perestroika, Western fascination with unofficial Soviet art reached its peak. Interest extended beyond journalists and diplomats to critics, collectors, curators, and gallery owners. Artists once ignored, or tolerated at best, by the Moscow Union of Artists suddenly saw their status transformed through exhibitions and sales abroad. High profile events, such as Sotheby’s first Moscow auction on July 7, 1988, conferred a form of informal protection and legitimacy, as the artists themselves had predicted would happen during the Bulldozer Exhibition.

Without the forceful international reaction, the event might have faded into obscurity. Understanding this in advance, the organizers deliberately invited every foreign correspondent and diplomat they knew, and nearly all attended, regularly holding informal press conference in his home over the years. The result was one of the most extensively documented events in the history of Russian contemporary art. The New York Times ran Wren’s story on its front page and literally overnight, the nonconformist artists found themselves known far beyond the vacant lot where their exhibition had been destroyed.

On September 16, two of the exhibition’s key organizers, Oskar Rabin and Aleksandr Glezer, published an open letter announcing that unofficial artists would return to the same vacant lot within two weeks for a second exhibition. This escalation carried real risk: undeterred by state pressure, the artists again faced the possibility of their works being destroyed by “vigilantes,” bulldozers, pressure hoses, or bonfires. Yet repeating the spectacle grew increasingly costly for the authorities, who risked another international scandal, especially since the artists were not technically breaking any law and showed no intention of stopping their activities.

As Andrei Alexandrov-Agentov, then head of the Communist Party’s Central Auditing Commission, later admitted the original crackdown only amplified the artists’ visibility: “This action caused a lot of unnecessary noise. It was the only thing that gave the ‘abstractionists’ the international attention they desired. If the artists had been given a room for the exhibition, accompanied by a few articles about their meaningless works of art, and given the public the opportunity to form their own opinion, everything would have resolved itself. However, by bringing in the police, using bulldozers and fire hoses, the Moscow City Council turned not only the ‘bourgeois’ press but also Western communist parties against the USSR.”

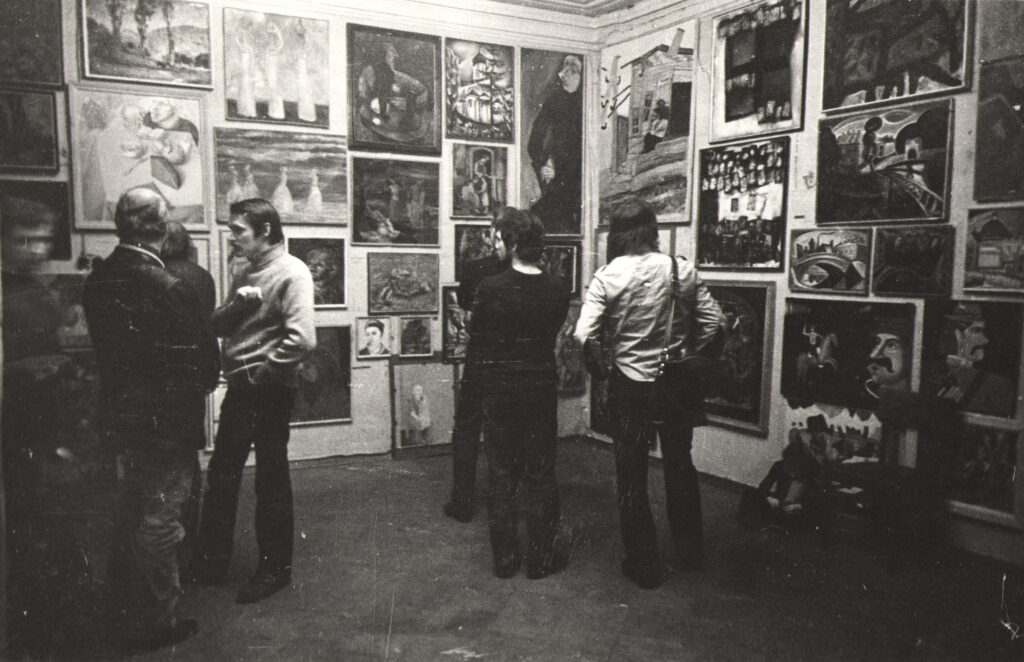

After three days of scandal across Soviet and international media, and negotiations involving the organizers, the KGB, and the Moscow City Council, permission was granted for the exhibition to take place in Izmailovsky Park. The decision came as a somewhat of a welcome surprise, as there was no guarantee that the artists would succeed in any capacity, with Glezer fearing the worst for himself most of all. “You’re artists, and they won’t do anything to you, but I’m a collector, and they’ll put me in jail,” he stated on multiple occasions. Held on September 29, it became the first of many informal exhibitions there and eventually evolved into the permanent Vernissage in Izmailovsky Park.

Even then, concessions were hard won. Officials attempted to fracture the community by proposing limits, first restricting participation to Muscovite artists and later suggesting separate exhibitions for Moscow and Leningrad artists. They also attempted to shift the date to September 28, subtly undermining the original plan. Despite these maneuvers, the exhibition proceeded, marking a turning point for unofficial art in the Soviet Union.

Over four hours, roughly forty artists, nearly twice the number involved in the original Belyayevo exhibition, presented around 250 works to a crowd estimated at anywhere from several thousand to as many as fifteen or twenty thousand spectators. The scale of attendance transformed the event into a quiet yet unmistakable assertion of endurance, widely interpreted as a moral victory over the state’s earlier use of force. It was not only the artists who prevailed but also a broader Russian intelligentsia that, after decades of suppression, publicly aligned itself with the nonconformists in defiance of recent repression.

Participants later recalled the exhibition as both celebratory and compromised. Artist and participant Boris Zhutkov observed that the overall quality of the work shown in Izmailovo was lower than at Belyayevo, largely because many of the strongest works had already been destroyed during the bulldozer attack. Even so, those four hours in the park came to be remembered as “the Half-Day of Freedom,” a brief opening in an otherwise closed cultural landscape.

The authorities themselves quickly recognized the damage caused by the initial crackdown. Upon learning of the Belyayevo incident, Yuri Andropov reportedly reacted with fury, condemning the destruction: “What idiot, what cretin would commit such vandalism?” It was likely due to this outburst that the state ultimately shifted course, granting permission for the Izmailovsky Park exhibition as well as later organizing an additional large-scale nonconformist show at the Beekeeping Pavilion at VDNKh, an implicit admission that the bulldozers had been a costly miscalculation.

Looking back in a 2010 interview with Snob, Vitaly Komar described the second exhibition as an unexpected turning point not just for artists, but for the country as a whole: “It was amazing. It was the first sign of perestroika, I believe. Not thirteen or fourteen artists came, but many more. And the audience was legion. It was some kind of amazing celebration. A real fair. Even if it was a vanity fair. The artists were very proud that they had finally become an object of interest.”

In later years, the damage control continued throughout the entire system, with officials and former security officers offered competing, and often self-serving, accounts of the events surrounding the Bulldozer Exhibition. At a meeting with voters, Moscow City Duma deputy Alexander Semennikov, a former Foreign Intelligence Service officer, emphasized the supposedly benevolent role of the security services, stressing that the exhibition took place in his district and insisting it was dispersed by the police, not the KGB.

A more different appraisal came from retired FSB Major General Alexander Mikhailov, who at the time served in the 5th Service of the KGB’s Moscow Directorate. Mikhailov described the dispersal as an example of party incompetence and short-sightedness, claiming it was the security services that later helped secure the third exhibition at the Beekeeping Pavilion at VDNKh, where the artists “could exhibit whatever they deemed necessary.”

Despite earlier reports to the contrary, it was found that many works confiscated during the Bulldozer Exhibition were not destroyed, eventually being relinquished and recovered by their creators. Former party official Anatoly Chernyaev later claimed that the paintings were quietly returned to their owners through an intermediary, an “unidentified woman,” accompanied by her apologies.

Chernyaev further stated that overt repression eased in the aftermath and that he could not recall any further dispersals. A fourth, semi official “permanent” exhibition followed, allowing twenty nonconformist artists to show their work at the Moscow United Committee of Graphic Artists building on Malaya Gruzinskaya Street. Chernyaev himself later recalled visiting and being struck by the unexpected level of artistic freedom on display.

Yet just beneath the surface, state opposition to unofficial art had not disappeared. Having failed to suppress it through intimidation alone, including threats and violence, authorities turned to a familiar Soviet tactic: reputational harassment through the press. Two newspaper articles addressing the Izmailovsky Park exhibition proved particularly influential. The first article, published in Vechernyaya Moskva (Moscow in the Evening) and written by People’s Artist of the USSR Fyodor Reshetnikov, creator of the well-known painting ‘Low Marks Again’, sought to dismantle both the exhibition and the artists’ credibility.

Praising socialist realism as the sole legitimate artistic method in a screed running approximately two pages, Reshetnikov dismissed the works on display as derivative and obsolete: “Everything I saw at this show reminded me of what I’ve encountered repeatedly at international exhibitions of so-called “avant-garde” art. And such “works” weren’t a revelation to me, as I’d already encountered such experiments in my youth. This whole replacement of painting with all sorts of trash took place here in Moscow at the beginning of this century. So why drag this outdated junk into today’s world and then pass this surrogate off as art?”

A month later, an even longer critique appeared under the name N. Rybalchenko. Framed in a conversational tone meant to echo the voice of the “ordinary Soviet citizen,” the article accused the artists of being self-absorbed and out of touch: “Apparently, the lack of contact with real life, the inability to understand and express the real world of man, forces the participants of the exhibition to reach for all sorts of symbols, allegories, for all these “alphas” and “omegas,” for various kinds of “overthrows” and “oppositions.””

Transcriptions of dialogue allegedly overheard by the author at the exhibition were used to reinforce this position, giving the impression of popular consensus. Yet, as art historian Anna Florkovskaya later observed, the criticism remained comparatively restrained. It lacked the ferocity of press campaigns from the 1930s and 1940s or Khrushchev’s attack on the Manege exhibition in 1962. By the mid 1970s, official condemnation increasingly appeared as private opinion rather than direct ideological decree.

No public response followed Reshetnikov’s article. Only after Rybalchenko’s piece did Aleksandr Glezer submit a rebuttal, never published, correcting factual errors and attempting to defend the nonconformist community. Written hastily and with evident anger, the letter nevertheless articulated a crucial point. Glezer argued that accusations of hostility toward Russian culture were an act of blame-shifting:

“[Ryabchenko] writes of the malicious intent of the artists who participated in the Izmailovo exhibition, which was “dictated by a hostile attitude toward Russian culture.’ ” This is what’s called in Russian: “to pour out the contents of a sick head into a healthy one.” No, it’s not the artists who want to exhibit not only abroad, but also, first and foremost, in their own country, who are hostile to Russian culture. It’s those who, on September 15th, drove bulldozers at artists and paintings, those who physically destroyed Vsevolod Meyerhold, the great Russian writers Osip Mandelstam, Boris Kornilov, and Isaak Babel, those who, for five decades now, have been hiding paintings by great Russian artists—Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, and Marc Chagall—from the Russian people deep in the storerooms of state museums.” In this inversion, Glezer captured the deeper moral fault line exposed by the events of 1974.

Oskar Rabin later admitted: “The exhibition was prepared more as a political challenge to the repressive regime than as an artistic event. I knew we would have problems, that there would be arrests, beatings. For the last two days before the exhibition, we were terrified. I was terrified by the thought that anything could happen to me personally.” Naturally, Rabin was no one-time participant seeking glory and attention. His advocacy for unofficial art continued throughout his life.

More to the point, the latest exhibition at the Committee of Graphic Artists was no longer another concession but a decisive plan by party leadership to completely end the phenomenon of unofficial art. Just as Melodiya had created an official outlet for people interested in western music, making the underground scene irrelevant, the Committee was intended to do the same for informal art intelligentsia. Nonconformist artists were now heavily encouraged to join the new group, wherein they can be more easily controlled. Those who refused membership would now be charged with the crime of “parasitism”. Rabin was one of the individuals who resisted.

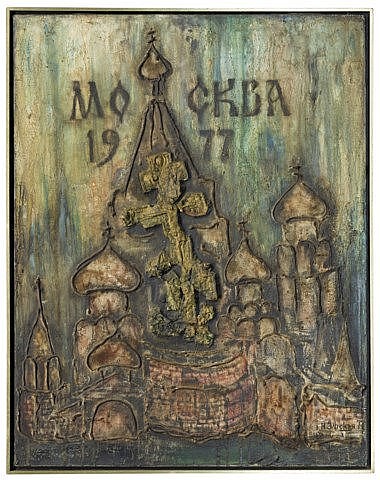

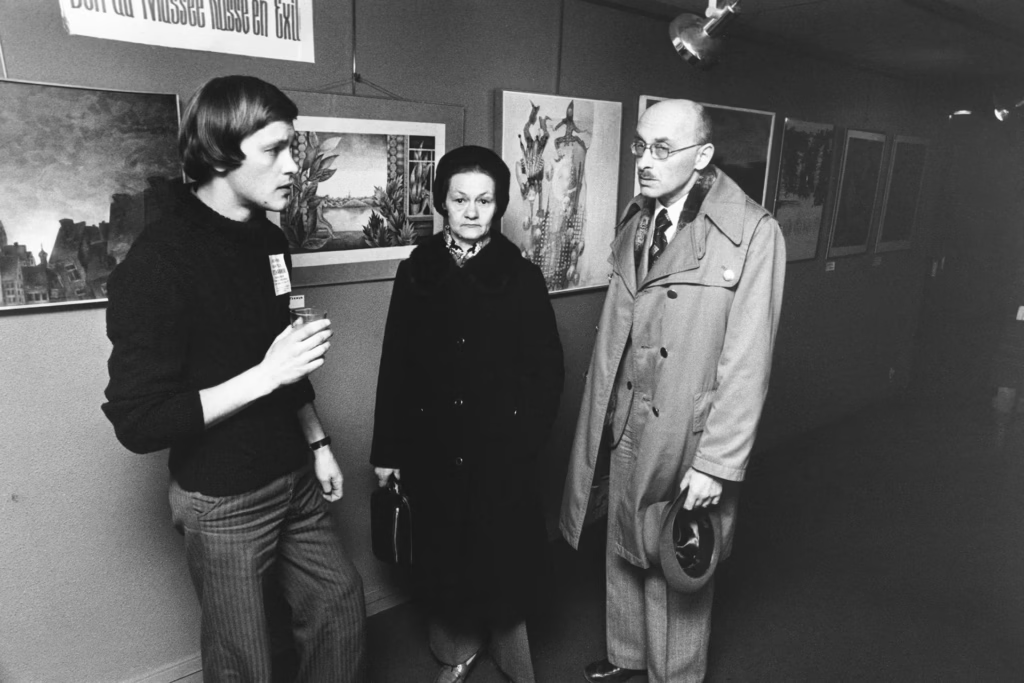

In 1977 he was charged with the very same crime and given an ultimatum: emigration or prosecution. After initially refusing and being briefly arrested, he later accepted departure under the guise of a family trip to Europe for tourism. Relocating with his family to Paris, the nonconformist art world had now lost its unofficial leader. Six months later, he was summoned to the Soviet embassy and informed that his citizenship had been revoked.

A year prior, the nonconformist art world suffered a separate blow with the death of Yevgeny Rukhin, another prominent member. Official reports attributed his death to carbon monoxide poisoning, though his wife believed it to be the result of a KGB operation, a suspicion shared quietly within the artistic community at the time.

Despite the easing of restrictions in the years to come, every artist continued to encounter difficulties in their own separate ways until the fall of the Soviet Union. Many, like Rabin, opted to emigrate abroad. Komar and Melamid, Viktor Tupitsyn, and Margarita Masterkova-Tupitsyn relocated to the United States while Vladimir Sychev and Aleksandr Glezer both eventually settled in France, all maintaining their ties to the Rabins. Those who stayed behind continued their work, despite being aware of the lingering risks of working outside of the system.

Still, the public perception of nonconformists artists had markedly changed as a result of their newfound exposure, and participation in the Bulldozer Exhibition was now seen as a badge of honor, easy to freely display. The nonconformist world even took a cynical turn, with some claiming to have displayed their works at the exhibition to further their careers, despite having declined the invitation or arrived late to the event, or not at all, as was the case with decliner Boris Shteinberg, who many still associated with the exhibition. The ensuing attention from the global art world also did little to minimize egos. As Vorobyov wryly states, “The next day, a nameless wasteland became a profitable business.”

Ultimately, the Bulldozer Exhibition stands as a major milestone in the history of Russian art, underscoring a fundamental truth: creative people not only need to produce work, but also to retain the right to show and circulate it, even when doing so carries real risks to their safety, livelihoods, and families.

Such struggles are far from confined to the Soviet past. In North Korea, artistic production remains tightly bound to state ideology, with official art still rooted in a Socialist Realist tradition that glorifies leadership, labor, and national unity. Independent artistic practice is effectively nonexistent in public life, and virtually no verified examples of unofficial or dissident art have emerged from within the country. Given the severe controls on expression and movement, it remains more likely than not that forms of underground or private creative resistance exist but remain unseen beyond the country’s borders. If so, their story, like that of Moscow’s nonconformist artists in 1974, may only come to light years or decades from now.

Elsewhere, challenges to creative freedom continue to surface in different forms. Across the United States, Europe, Asia, and once again in Russia, artists and cultural institutions regularly face political pressure, censorship disputes, or social and economic constraints that shape what can be shown and where. In this light, the events of 1974 continue to resonate, serving as a reminder that the struggle over artistic freedom is not confined to one place or era, but remains an ongoing global concern.

At the same time, the events have served as creative fuel for contemporary artists across many media. Moscow-based game developer, filmmaker, and interdisciplinary artist Mikhail Maksimov created an eponymous game inspired by the events. The objective is simple: drive the bulldozer through the forest and destroy as many paintings as possible within a set time limit. Artists themselves are also fair game, but take care not to run over foreign journalists, lest you ignite an international incident. The ironic reversal of roles highlights the absurdity of the event and forces participants to confront the logic of censorship from the seat of the censor himself.

As Oskar Rabin later reflected, the bulldozer became a blunt symbol of authoritarian power, as unmistakable in its message as the Soviet tanks that rolled into Prague in 1968. Two of his own works, a landscape and a still life, were destroyed, either flattened by machinery or burned during the crackdown. Yet the destruction failed in its ultimate aim. As many participants later observed, some of the works were lost forever, but the movement itself survived, adapted, and ultimately endured.

Half a century later, on the fiftieth anniversary of the exhibition, artists, historians, and supporters returned to the same vacant field where the original show had been crushed. Now a tradition from previous anniversaries, they brought a bulldozer of their own, not as an instrument of intimidation, but as an object stripped of its former menace, declaring a symbolic victory over it. The gathering functioned less as a reenactment than as a quiet act of remembrance, reclaiming a place once meant to erase them from public life.

The officials who ordered the crackdown, the operators who drove the machines, and the structures that once enforced cultural conformity had largely disappeared or directed their attention elsewhere. Meanwhile, the artists, and the art they fought to show, had entered museums, archives, and art history itself. What was once dismissed as dangerous or worthless had become part of the cultural record. In the end, the Bulldozer Exhibition was never only about paintings in a vacant lot. It was about who has the right to speak, to create, and to be seen.

The operators and organizers of the crackdown were nowhere to be found, yet the artists remained, and so did the bulldozer, now with no one left to drive it.