Before retreating from the spotlight, Chris Cunningham, the elusive director behind the music videos for Aphex Twin and Björk injected sci-fi dystopia and body horror into some of the most unusual commercials of the late 1990s.

Today, Chris Cunningham is best described as reclusive. In the last decade he has released only a single public work, and accounts differ as to why he stepped back from the public eye. In the 1990s, however, he was everywhere, a pioneer across music, film, and advertising. When people think of the name Chris Cunningham, the famous (or infamous) videos he did for Björk, Autechre, Aphex Twin, and others immediately come to mind. Some videos won awards in some countries, those same videos were awarded bans in other countries, and still many continued to court his talent, so he is no stranger to controversy nor mainstream appeal.

Cunningham was a powerhouse. Before directing, he came up through special effects. Raised in Cambridge, he left home at 17 for London after years of building creatures and effects in his garage (he had already been a designer for Clive Barker’s Nightbreed and Hellraiser 2 at 16–17). At 19 he entered film professionally on Richard Stanley’s Hardware (1990), working on robotic effects. He later contributed creature work to David Fincher’s Alien 3 (1992), specializing in biomechanical alien fabrication under the pseudonym Chris Halls, a name he had already used while moonlighting as an illustrator for British comics.

Between 1990 and 1993, he produced cover art, pinups and interior illustrations for 2000 AD and Judge Dredd Megazine, including direct collaborations with Garth Ennis. He sculpted elements of Sylvester Stallone’s costume for Judge Dredd (1995), and was eventually headhunted by Stanley Kubrick with whom he worked for 18 months on the unmade version of A.I. which included designing its animatronic robot. Kubrick never completed the project before his death and Steven Spielberg eventually finished the project, but the experience shifted Cunningham’s focus. He realized he was becoming more interested in image-making than in servicing other directors’ visions.

“I had a burst of self-confidence,” he later said, describing how he approached Autechre in 1995 to direct what became Second Bad Vilbel (1996), his formal debut behind the camera. What followed was a concentrated run of music videos for Portishead, Madonna, Squarepusher, Afrika Bambaataa and others. A career run that has aged unusually well and remains difficult to separate from the visual identity of late-90s electronic music. But we’re not here for his music videos, that is a story that deserves a piece all of its own.

Today, the focus is elsewhere. During that same period, Cunningham was also building a parallel body of commercial work, often just as provocative, sometimes more constrained, and occasionally stranger than the music videos that made his name. In collaboration with major brands and agencies, he translated his interests in anatomy, science fiction, distortion and sound into the language of advertising. Here’s a survey of those commercials, moving from the relatively conventional to the genuinely unsettling.

Up And Down, Levi’s (2002)

Cunningham’s entry into advertising ran parallel to his early music video work. In 1996 he was approached by Kinsman & Co to direct a test commercial for the National Union of Students through London-based ad agency Mustoe Merriman Herring Levy, his first commercial commission. That piece never surfaced publicly, but it opened the door to his presence in the advertising world.

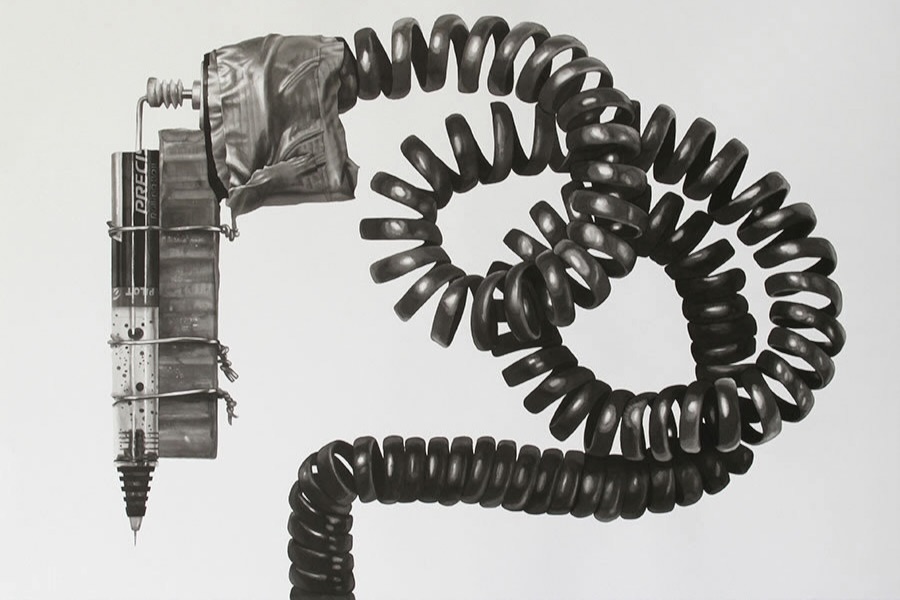

Years later, Up and Down, a Levi’s campaign for their line of women’s Superlow Stretch jeans, demonstrates how easily he moved into the advertising format while retaining elements of his visual language: tight edits, controlled movement, and an emphasis on physicality. It is not the most overtly “Cunningham” piece in his catalogue, in fact, it could almost pass as someone else’s work, but the concept is clean and direct. A single pair of Levi’s jeans is worn and removed by women of different backgrounds and styles to the sound of Basement Jaxx’s Do Your Thing, stressing universality and durability. The closing line, “Give your hips a hug,” is superimposed over a close-up of those same hips.

On the surface it is straightforward, even conservative by his standards. Yet something remains distinctly his. The women’s faces are never shown. Identity is secondary to the body. The framing carries a faint detachment: impersonal, slightly voyeuristic. Even at his most by-the-numbers, Cunningham gravitates toward abstraction and anonymity.

Flora by Gucci (2009)

Cunningham’s campaign for the perfume Flora stands apart from most of his commercial work, not only because it arrived in 2009, well after his late-90s peak, but because it appears, at first glance, almost anti-Cunningham. The palette is bright and saturated. The theme is floral, romantic, overtly feminine. There is no horror, no dystopic themes, no visible distortion.

Years before, he has spoken positively about the constraints of advertising: “I really love the discipline of directing commercials and being given a proper, rigid brief. Most directors find it restricting but I don’t want to do a director’s cut of 60 seconds and then an ad cut of 40 seconds. You shouldn’t feel the need to do that.”

The commercial stars Australian model Abbey Lee. She stands waist-deep in a vast field of white flowers, wearing a flowing floral-print dress, backlit by a low sun. Shot over four days in Latvia, the production constructed the setting using more than 20,000 artificial flowers. As the sequence unfolds, she appears to command the wind itself, the field rippling under her control as her dress and body transform into a butterfly-like abstraction of fabric and golden light, almost Rorschach in symmetry. The emphasis is on sensuality, but also on self-possession and strength.

Gucci had previously collaborated with David Lynch to launch Gucci by Gucci, and creative directors Patrizio di Marco, Frida Giannini and agency head Remo Ruini wanted an equally distinct vision for the new fragrance. Working with FilmMaster in Italy and Ridley Scott’s RSA Films in London, Cunningham oversaw the project from concept to execution.

Sound was central. Gucci chose to build the film around Donna Summer’s 1977 classic I Feel Love, retaining a 70s sensibility. With Cunningham’s established reputation for musical precision, they invited him not simply to sync the track but to re-record and produce a new arrangement. He traveled to Nashville to re-record vocals with Summer herself. The result was an ethereal rework of the original, with the vocals coming in faintly, slow and subtly suggesting to you that this, in fact, I Feel Love, as if the viewer is remembering a distant, cherished memory. Ruini later said the team was “blown away” when they first heard the new version matched to Cunningham’s imagery.

Despite his usual predilection for darker genres and his prior work in the electronica genre, Cunningham is no stranger to disco and funk sounds. He often combines the two worlds. A year prior to the Gucci campaign, he remixed Grace Jones’ Williams’ Blood and collaborated with her on a photoshoot, for him a rare venture into still photography. Speaking of that project, he described bringing in a trombone player to produce low, almost threatening horn tones inspired by personal favorite composer Edgard Varèse: “Varèse is more evil-sounding than the darkest dubstep bass.”

His approach to sound design, whether disco or industrial, is obsessive. In 2004 he took on a multi-year sabbatical from filmmaking to learn about music production and recording. For one project, he recorded the harmonics of trains near his home at night over the course of several years, attempting to replicate or integrate those tones into compositions. This later informed his later work on Gil Scott-Heron’s I’m New Here, including a remix and visual reinterpretation of “New York Is Killing Me,” where field recordings, subway imagery and electronic manipulation converge.

Seen in that context, Flora by Gucci is less a departure than a recalibration. The dystopic horror is gone, but Cunningham’s control over atmosphere, rhythm and transformation remained absolute. This would also not be his last appearance in the fashion world. As recently as 2021, Cunningham created the visuals and sound for Dior’s 2021 Spring/Summer collection.

Clip Clop, XFM (1998)

By the time he directed Clip Clop, Cunningham had been signed to RSA Films for music videos (since April the previous year) and was already moving between music and advertising. Around the same period he had directed work for Aphex Twin and Britpop band Jocasta, he was hired to handle Saatchi & Saatchi’s launch campaign for XFM. Though he continued making music videos through RSA’s Black Dog Films division, at the time he expressed interest in concentrating more heavily on commercials.

What concerned him was typecasting. Often, the music videos he directed leaned into a dark, slightly unsettling atmosphere, but Cunningham resisted the idea that this defined him. “People think my work is really sinister, but it’s because that was the required style. If people start categorising me, I’d be really fucked off and I’d probably give up directing,” he said at the time.

This commercial, on the other hand, is structurally simple and rather whimsical. Rapid cuts of everyday London: parks, pavements, dogs being walked, cars passing, footballs kicked against brick walls. The only twist is that all of the sounds have been replaced with anything but what the visuals are supposed to sound like, often to a cartoonish degree. Naturally, the line at the end reads: “Alternative sounds for London.”

The context is interesting. XFM had only recently transitioned from being a pirate radio station to licensed broadcaster, becoming legal roughly a year before the campaign aired. The ad functions as a reintroduction, positioning the station as part of the city’s everyday fabric while simultaneously reframing it. Familiar visuals, unfamiliar sound. An invitation to hear London differently.

Quiet, Telecom Italia (2000)

Like his encounter with Grace Jones, Cunningham’s work has never been confined to underground figures; he has frequently collaborated with major cultural names. For Telecom Italia, he directed a commercial featuring a young Leonardo DiCaprio at the height of his post-Titanic visibility.

The film is restrained and contemplative. DiCaprio lays down in a vast field, immersed in a quiet, almost meditative pause. Close-ups of insects climbing blades of grass punctuate the sequence. Boards of Canada, another IDM act often mentioned in the same conversations as Aphex Twin and Autechre, provides the soundtrack, characteristically warm, analog, slightly melancholic. The calm is briefly interrupted when he checks an incoming message on a Palm Pilot, a then-contemporary symbol of portable connectivity, the message asks him when he will return, presumably to the hustle and bustle of interconnected city life. Leaving it unanswered, he puts the device aside and returns to his stillness. The closing line reads: “Technology is important, but so is everything else.” As the text fades, a faint number-station tone lingers.

Unlike much of Cunningham’s reputation-defining work, there is nothing overtly disturbing here. The mood is pensive, hopeful, and airy rather than confrontational. The technology is present, but peripheral. It suggests wistful balance rather than domination, a theme that would reappear years later in the Flora by Gucci campaign, where pleasant atmosphere and restraint carried the message.

It’s worth noting that the music used in the commercial is unreleased material from Boards of Canada. Cunningham has long been friends with the members of Boards of Canada, and in advance of the project they personally provided Cunningham with about 90 minutes’ worth of music, of which they estimate only 20 seconds was actually used. Despite their participation, they expressed a particular contempt for DiCaprio and his involvement in the project. “He utters one word. God knows what he got paid. We wanted to record ‘Leonardo Dicaprio is a wanker’ and put it in the advert music backwards.” the group stated in a 2000 Jockey Slut interview.

Sport Is Free, ITV (1997)

Cunningham’s earliest work that made it to the air, Sport Is Free leans fully into dystopia, a compact piece of world-building that seems to anticipate the atmosphere of Cuarón’s Children of Men and feels, in hindsight, uncomfortably close to the gated, subscription-driven future of media consumption where ownership is nonexistent. A man approaches a counter and feeds coins into a slot. Behind reinforced glass, an attendant directs him to a private viewing booth. Through a narrow slit he can see a distant television broadcasting a sports match. As he watches, the slit begins to close. He inserts more coins to keep it open. The act of viewing becomes transactional, claustrophobic, almost illicit, less like public broadcasting and more like the discrete porno theaters of old, before the dawn of home video.

The premise is simple but effective: sport as rationed spectacle, accessible only through controlled, monetized apertures. Cunningham builds an entire social structure in under a minute. The viewer instinctually remembers how happy he is to be in a world where sports are not confined to small rooms with slots and that ITV exists for free viewing at home. That instinct for constructing enclosed systems runs throughout Cunningham’s work, as if he was always treating every project like practice for a much bigger yet to appear on the horizon.

This was all but confirmed confirmed by the man himself. Cunningham’s long-stated ambition has been to direct a feature film himself. He once spent four years developing a short film he ultimately abandoned without screening to anyone, a zombie movie, according to collaborator Aphex Twin. In another case he expressed a desire to direct an action film. Most prominently, he spent three years in discussions to adapt William Gibson’s foundational cyberpunk novel Neuromancer, before stepping away (to everyone’s disappointment), concluding he could not make it fully his own. “You can become so obsessive that you become almost inactive,” he said. “You could spend years on a film and then not have the final say.”

In a 1999 interview with Spike Magazine, William Gibson described Cunningham as his “100 per cent personal choice” to direct Neuromancer. Gibson recalled being told that Cunningham was wary of Hollywood and reluctant to engage with the studio system. “Someone else told us that Neuromancer had been his Wind in the Willows, that he’d read it when he was a kid,” Gibson said. They eventually met in London shortly after Cunningham completed his video for Björk. Gibson remembered sitting beside “this dead sex little Björk robot, except it was wearing Aphex Twin’s head” while they talked, a fitting image for a director whose commercial work often feels like fragments of larger, unrealized worlds.

At one stage, development funding was secured through Warp Films for his first feature, with Cunningham committed to the company for “all future full-length film projects.” However, this still amounted to no meaningful progress and he later left Warp to establish his own production company, CC Co., in order to maintain independence. To date, his only completed narrative film remains Rubber Johnny (2005), a short body-horror piece starring Cunningham himself, scored by Aphex Twin and distributed by Warp.

Fetish, NUS (1998)

Another film-like production, Fetish plays like a short film disguised as a public service announcement. Charlotte, a young woman, moves through a world of self-invention and transgression: tattoos, piercings, shaved heads, body modification, the pursuit of sensation as identity. Cunningham frames her not as caricature but as someone methodically chasing the next threshold and giving her earnest thoughts about it as if being interviewed in a documentary.

The tension builds as she prepares for what appears to be another extreme procedure. She lies back on an operating table. The clinical lighting, the close-ups, the anticipatory stillness, everything suggests something invasive. Then comes the turn: she isn’t undergoing a modification at all. She’s donating blood.

It’s a sharp subversion of expectations, particularly in the late 1990s, when alternative culture was edging into the mainstream but still carried a charge of taboo. Cunningham exploits the viewer’s assumptions about “fetish” and bodily extremity, only to redirect them toward civic responsibility. The sponsor, the National Union of Students, the same organization that had previously brought in Cunningham to create his first test commercial, positions blood donation not as obligation, but as another form of meaningful intensity.

Cunningham has often said that his interest in commercials ran parallel to his love of cinema. According to him, he learned how to produce short films “by watching commercials with the sound down for a year until I figured out how they were put together.”

When he speaks about film, it’s with the enthusiasm of someone shaped by it early. By his own admission, he was obsessed with Alien, Blade Runner, The Bionic Man, and The Elephant Man as a child to the point that he could have told you who the gaffer was on those productions. That obsessive attention to atmosphere, texture, and world-building, even in under a minute, is what gives Fetish its weight beyond the twist.

Photo Messaging, Orange (2003)

Cunningham’s commercial for the now-defunct telecom provider Orange is one of his most overtly digital works: a slick, effects-heavy meditation on mobile phone photography at a moment when camera phones and sending messages in the form of images were still a novelty. The narrator provides a short lesson on photography. The advice is decidedly formal: make sure poses are dignified, nobody is moving, and everyone is ready and facing the camera. Yet quite the opposite unfolds in the film: people and animals are frozen mid-motion, suspended in three-dimensional space. A dog hangs in mid-leap, an impromptu football match preserved in motion blur as the players wear suits and ties, dancers at a party caught mid-stride, people are laughing and talking to each other, looking anywhere but the camera. It feels like a Francis Bacon painting or a Muybridge experiment updated for the early 2000s, as if the focus was the movements more than the people producing them.

The mismatch is intentionally ironic. Here, imperfections are aestheticized and the phone becomes less a communication device and more a tool for capturing, even arresting, reality. The visual concept aligns neatly with the brand’s pitch: “muck about”. Do whatever, even if it doesn’t look perfect, and break with old conventions by using the new medium of cell phone photo messaging.

The moment’s hyperreality is further emphasized by its soundtrack: Add N to (X)’s Barry 7’s Contraption, a deceptively ambient piece that grows to involve synthetic and defiantly experimental elements as it builds. It’s an unusual choice for a mainstream telecom advertisement, but entirely consistent with Cunningham’s instincts. He has always gravitated toward electronic texture and mechanical rhythm, even when working within commercial constraints.

In interviews, Cunningham has credited his father and stepfather with laying the foundations of his musical education, the former introducing him to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon and Tomita’s Snowflakes Are Dancing at the age of 7 and the latter showing him the synthesizer-driven soundscapes of Vangelis and Tangerine Dream while they were living in the village of Lakenheath. The village sat beside a U.S. Air Force base populated almost entirely by American personnel, and through his proximity to the servicemen there he encountered hip hop which also provided an early influence on his taste. According to him, the collision of cinematic electronica and imported rap culture formed his earliest musical background.

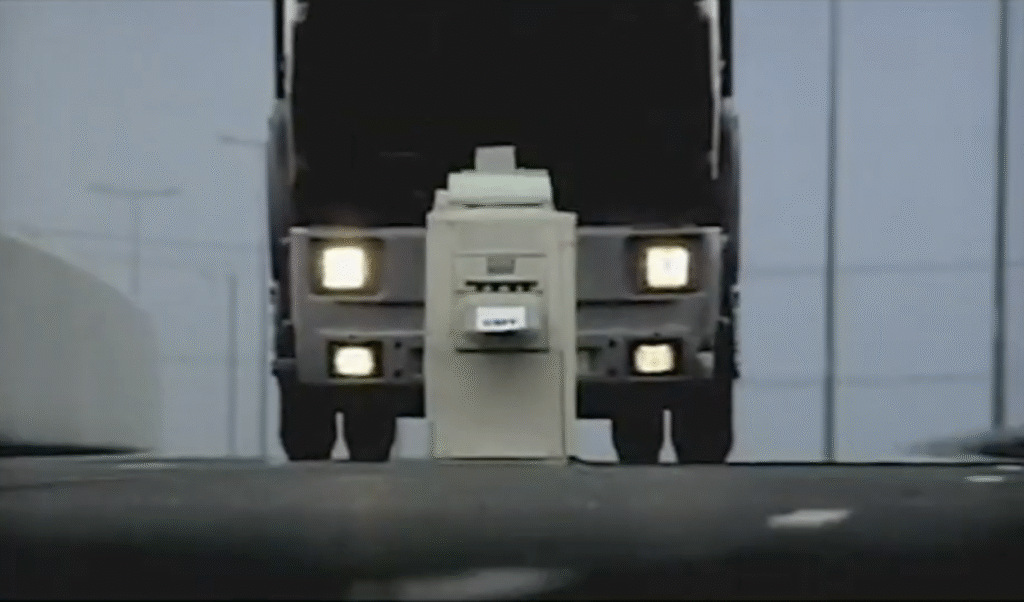

Photocopier, Levi’s (1998, Unaired)

There is something characteristically Cunningham about the fact that one of his most aggressive commercials was never aired. Produced for Levi’s in 1998 and ultimately shelved, the film only surfaced years later as part of a DVD compilation of his work.

The premise is stark and unnarrated: a photocopier churns out endless sheets of paper in a sterile interior. The papers have only one word on them: “copy”. The mechanical repetition builds into a kind of quiet hysteria. Then, without warning, the machine is obliterated by a colossal freight truck, which tears through the space and scatters paper across the road in a blizzard of debris. The violence is abrupt, industrial, almost gleeful, the small, domestic machine crushed by something infrastructural and unstoppable. Not one pair of denim is seen throughout the entire commercial. The message is clear: originality only.

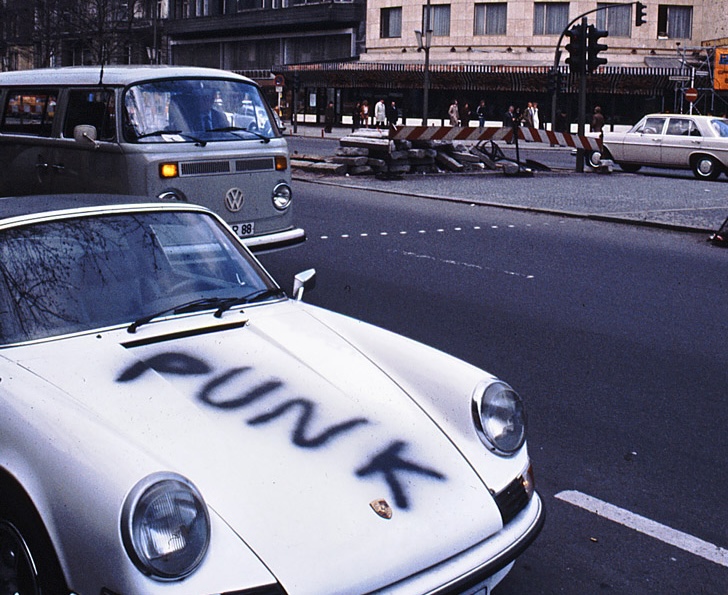

Even though it may have been seen as too original, ironically enough, it is an image that taps directly into Cunningham’s long-standing fascination with machinery and menace, as robotic bodies and industrial atmospheres captivated him from an early age. That early fixation on the mechanical and the uncanny would crystallize into an aesthetic that fuses visual impact with emotional intensity. In retrospect, the destroyed photocopier feels less like a product metaphor and more like an eruption of that sensibility into the advertising space. It’s a shame the piece never aired.

A few years later, Levi’s would, of course, bring him back to direct a far more restrained commercial, the comparatively tamer, denim-focused piece discussed earlier, suggesting that even brands drawn to Cunningham’s edge sometimes preferred it slightly blunted.

Instruments + Engine, Nissan (1999–2000)

In a way no American commercial would ever be allowed to do, Cunningham acquaints the viewer very intimately with the human body, and uses them as the focus of a car commercial. Where other car commercials would sell you convenience or a certain aspirational lifestyle, there is no car visible in the commercial until the very end. for most of it, there are instead pale naked bodies that are in varying states of distress or performing miraculous feats of physical ability.

The commercial’s narrator is coldly clinical “In your lifetime, you’ll spend around six years in a car. You’ll be insulted by other drivers over 400 times. You’ll spend seven months in traffic jams. Almost 40% of you will develop back trouble. More than 30% of you will fall asleep at the wheel, and you’ll encounter thousands of road bumps.” At last, the car appears, and the narrator then turns holistically optimistic, “The performance of a car is not the only thing that matters. It’s the driver’s performance that counts. If you feel good, you perform better. That’s why we’ve designed everything around your body. Around you.” The end.

The second commercial of the series is a silent demonstration of physical action to represent the features of a car. A man long jumps into muddy water while a text mentions the car’s brake assist system. A muscular man’s torso is contorting in almost inhuman ways, set to mechanical sound effects, the text emphasizes perfect control. The camera pans up from the ground, as a naked man rises, his back turned to the camera, and splays his arms out, the text emphasizes perfectly positioned instruments so your eyes spend more time on road, the words directly superimposed over the man’s buttocks, leaving the viewer no choice but to witness them if he were planning on reading the text.

“I’ve definitely got a total obsession with anatomy, but it’s very specific.” Cunningham admits. Here, the body is not glamorized; it is examined, stressed, pushed toward its limits, and most importantly, likened to a machine. The effect is intimate and faintly unsettling, closer to a medical study or a sci-fi experiment than a showroom pitch. The avoidance of presenting the body as the object of desire or aspiration is an idea that ran through Cunningham’s other work at the time. The subversion of hip hop’s sexualization of the female form is a major theme in his video for Aphex Twin’s Windowlicker, in which the video’s extras all have their faces replaced with prosthetic masks bearing the face of Richard D James, or Aphex Twin. Interestingly enough, the most grotesque mask of all directly inspired a set of drawings by H.R. Giger, also titled Windowlicker. In a roundabout way, Cunningham managed to inspire one of his own earliest sources of inspiration.

For this commercial, sound is just as central. The score once again came in the form of more unreleased music from Boards of Canada, except this time much less peaceful and more alien and dissonant, a left-field choice for a multinational car brand, but consistent with Cunningham’s long-standing attachment to the importance of soundscapes. His listening history runs wide: Bartók, Debussy, Varèse, Ligeti, Pavement, Kraftwerk, early Depeche Mode, mid-period Pink Floyd, DAF, and the numerous film scores he heard from his formative years.

The foundational idea of entering another sensory plane defines the Nissan work. The commercials feel less like product demonstrations than controlled environments, built from texture and tone. He was seemingly given unusual creative freedom: the pacing is drawn out, the imagery confrontational, the audio immersive. Possibly the most avant-garde car commercials ever created.

Like no other commercial (except the next and final one on this list) does this work underscore Cunningham’s interest with the human body and body horror. The emphasis on flesh under pressure also anticipates what followed. Soon after, Cunningham produced Flex (2000), a 15-minute installation looping a naked man and woman suspended in darkness, shifting between tenderness, sex, and violence before dissolving into light. The continuity is clear. In his Nissan spots, Windowlicker, and Flex, the body is no decoration. It is the site of collision between vulnerability and force as well as organism and mechanism.

Mental Wealth, Playstation (1999)

While he was shaping the Nissan campaign, Cunningham delivered what would become one of the most talked-about PlayStation adverts ever made. Mental Wealth, in its efforts to sell a console, ended up unsettling an entire audience, and this was entirely by design. The spot became an international talking point, provoking confusion, fascination, even outrage. Again, that reaction was not accidental. At the time, Sony’s PlayStation marketing leaned heavily into the strange and confrontational, positioning gaming not as family entertainment but as a psychological frontier befitting a new medium of human expression, a paradigm shift just in time for the new millennium.

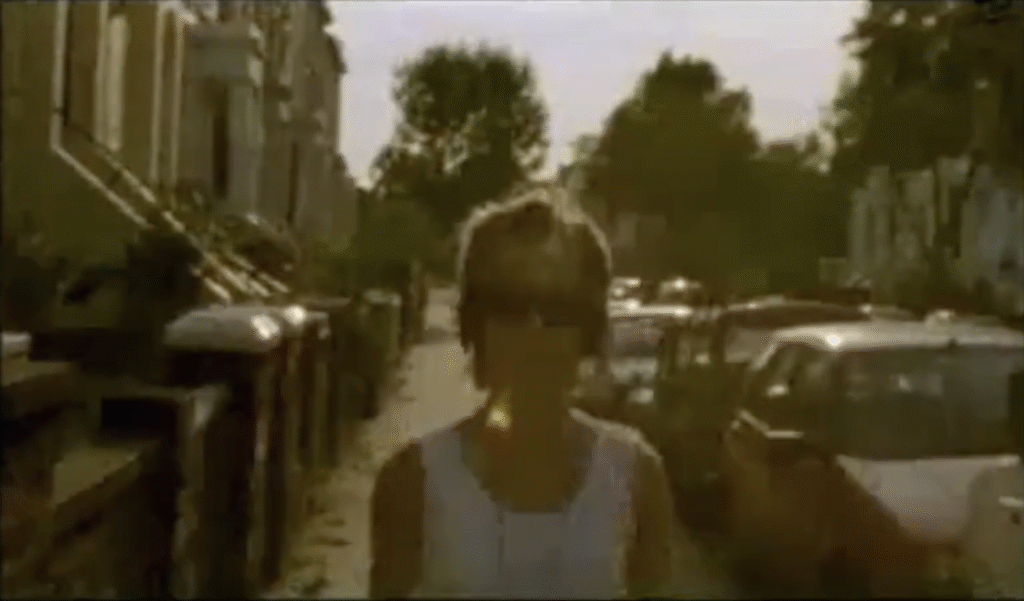

The commercial is disarmingly simple. A teenage girl, played by a 17-year-old child actress and dancer from Scotland, sits in a bare, almost institutional room. She speaks directly to camera about human potential, evolution, achievement. But her face is wrong. Digitally distorted, her features are grotesquely exaggerated: eyes too wide, mouth stretched, proportions skewed just enough to be deeply uncanny. The experience feels like finding lost media that was never meant to air, or as if test footage for some project was accidentally broadcast onto television instead of the finished product.

The dissonance is the point. The monologue frames gaming as the next stage of human development, a sharpening of reflexes, cognition, and imagination. The distorted face becomes a metaphor: not deformity, but mutation. Playstation as evolutionary leap. The individual so advanced so as to be incomprehensible when viewed from the past. ultimately, the girl suggests the viewer look within for a sense of achievement and to “land on your own moon”.

The aftermath was as strange as the advert itself, the commercial was the subject of massive discussion and coverage in the press. The actress, Fiona Maclaine, later described how tabloids secured exclusive rights to reveal her true appearance. “I think it was The Sun who had the rights to the story, the unveiling of what I actually looked like.” She said in an interview, “They told me not to let anyone take a picture of my face so that their exclusive wouldn’t be blown. Then one day I woke up and there were paparazzi outside my house! Not loads, only two or three, but I was living in this little flat with my mum at the time and was quite unlike anything that went on around there. I remember wrapping my face in a scarf and running to the car when I had to leave. And then The Sun revealed my real face. I think I got interviewed by BBC News too. And then I got recognised a fair bit. Even now, twenty-years later people seem to find me on the internet and send me emails saying, “hey, are you the girl from the old PlayStation advert?””

She has also reflected that the commercial’s impact was partly a product of its era. In 1999, audiences were less fragmented (less online, perhaps?) and strange images had room to linger. “But at the time, I certainly hadn’t seen that kind of technology of manipulating someone’s face before. People genuinely thought that’s what I looked like. It felt so new.” Viewers genuinely questioned what they were seeing. Even she didn’t know exactly how her face would be altered until the commercial aired. For Fiona, it was her first major acting role, one that led to further work and, as a footnote, a complimentary PlayStation which she admits she barely used but did get some enjoyment out of.

What Mental Wealth demonstrates more clearly than almost any of Cunningham’s commercials is his interest in the body as mutable surface. Technology doesn’t sit beside humanity; it reshapes it. It also perfectly shone a spotlight many had with regards to technology at the turn of the century and what dangers, if any, its rapid advance might have posed to humanity at the time. It also highlighted a prevalent anxiety about the reliability of the image, one that faces renewed attention now, in the age of generative artificial intelligence.

Conclusion

For all the innovation he brought to commercials and music videos, Cunningham has long expressed ambivalence about the industries that made his name. He has since left the advertising world behind, later offering a stark reassessment of the industry: “Making commercials is the dustbin of film-making. It sucks you dry.”

It’s a striking remark from a director whose advertising work consistently stretched the limits of the form. Yet the contradiction feels honest, and it has much to do with his approach to maintaining the purity of his creative vision. Much of his career has been defined by resistance, seemingly testing how much atmosphere, subversion, or abstraction a commercial can bear before it ceases to function as one.

Yet it’s also that unwavering commitment to artistic integrity that has earned Cunningham respect from his collaborators. Despite failing to bring Neuromancer to the big screen, the novel’s author praised Cunningham’s refusal to cede creative authority. “I find it inspiring that Mr. Cunningham had the strength not to compromise his vision for a project. The temptation is that even if the film were to turn out trite, the exposure would have given him instant house-hold name recognition and a big pay-day.”

Twelve years after the Nissan campaign and three years after his last traditional commercial, Cunningham returned to collaborating with a car company, this time Audi, in a format that edged far closer to installation art than advertising. The idea had been forming as early as 2002: a project that fused his interdisciplinary instincts with the mechanical obsessions of his childhood. It took nearly a decade to secure the funding to realize it.

Presented at Audi City in London’s Piccadilly, Jaqapparatus 1 centered around an exposed engine encircled by two industrial robots. In a dark, smoke-filled space, they moved in choreographed bursts, firing light and lasers to a metallic, industrial soundscape produced by Cunningham himself. The result felt less like a showroom attraction than a ritual staged by machines. True to his recurring impulse toward world-building, Cunningham originally imagined a central character – “sort of like a foreman,” he explained to Interview. “He’s not in this version because I didn’t have time to get him worked out. This installation is almost like a background of his universe.”

He described the piece as something developed intermittently over many years, with the implication that it would continue evolving. By this point, conventional film structures no longer seemed able to contain the kind of work he wanted to pursue. Jaqapparatus 1 made that clear: it was neither advertisement nor cinema, but a hybrid: machine, sound, and spectacle fused into a single controlled environment. If the feature film project of his dreams continued to remain elusive, commercials and music videos were no longer sufficient substitutes.

Taken together, from the most confrontational commercials to projects like Jaqapparatus 1, the through-line becomes apparent. Cunningham’s real preoccupation has never been the product itself, but the construction of total environments: spaces where sound, light, machinery, and the human body collide, operating beyond the usual constraints of runtime, messaging, or market logic.