Stories of Japanese audiophiles installing personal utility poles have become legend, but behind the myth is a shrinking, aging subculture chasing an ideal few can hear.

Japan has a reputation for turning personal interests into lifelong disciplines, pursued with a seriousness that borders on devotion. Audiophiles are no exception. Within this niche subculture, digital sound is dismissed as inherently tainted, while analog listening is treated as a kind of ritual, one that demands not just the right equipment, but the careful purification of electricity, architecture, and environment until nothing remains but sound itself.

Recently, I discovered Takeo Morita, an 82-year-old retired lawyer from Tokyo, known as the “rock grandpa” in his local community. In 2016, Morita made headlines abroad after a Wall Street Journal profile showed off his personal audio system that already exceeds what most listeners would consider extravagant: a $60,000 American-made amplifier, 1960s loudspeakers that came from a former movie theater in Germany, and a carefully assembled collection of top-tier components, including cables threaded with gold and silver.

Yet even this system failed him. “I found that I had long listened to music filled with noise. I could not stand it anymore,” he said. The source of the problem, in his view, was tainted electricity, interference caused by sharing a power supply with neighbors and household appliances.

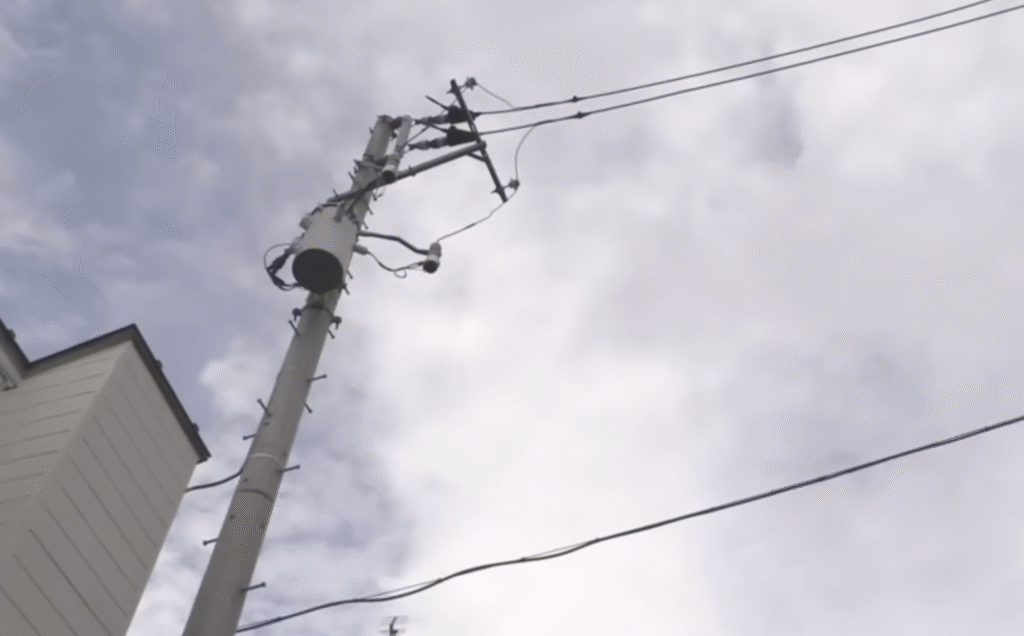

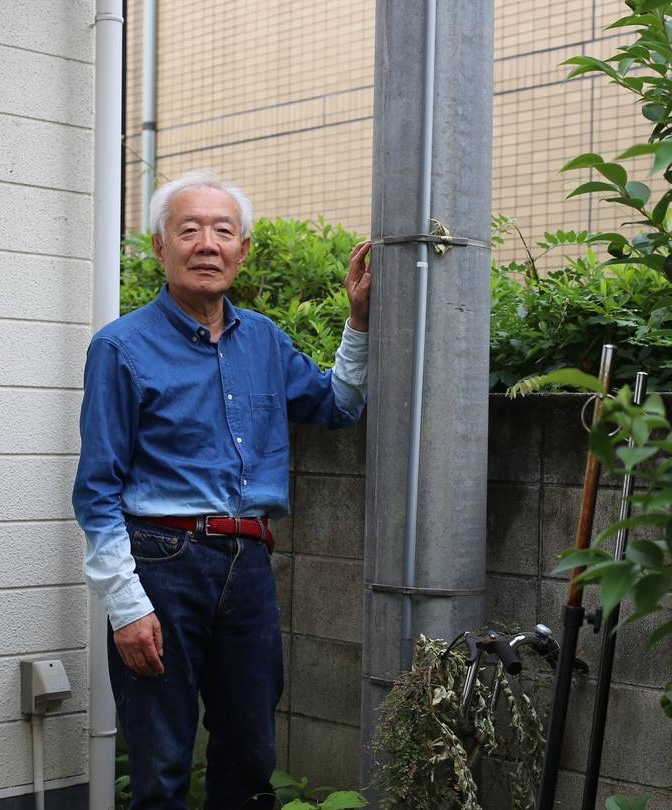

As anyone would do, Morita’s solution was to install a personal 40-foot utility pole in his yard at a cost of $10,000, connected directly to the power grid through a transformer to supply what he believes is the cleanest possible current. “Electricity is like blood,” he explained. “If it is tainted, the whole body will get sick. No matter how expensive the audio equipment is, it will be no good if the blood is bad.” The first song he played after installing the pole? Queen’s 1975 I’m In Love With My Car.

Others have reached similar conclusions independently. 62-year-old banker Yukio Yoshihara noticed that his expensive system sounded better late at night, when neighbors were asleep and electrical demand was low. After consulting electricians, he became convinced that his home’s power supply was polluted.

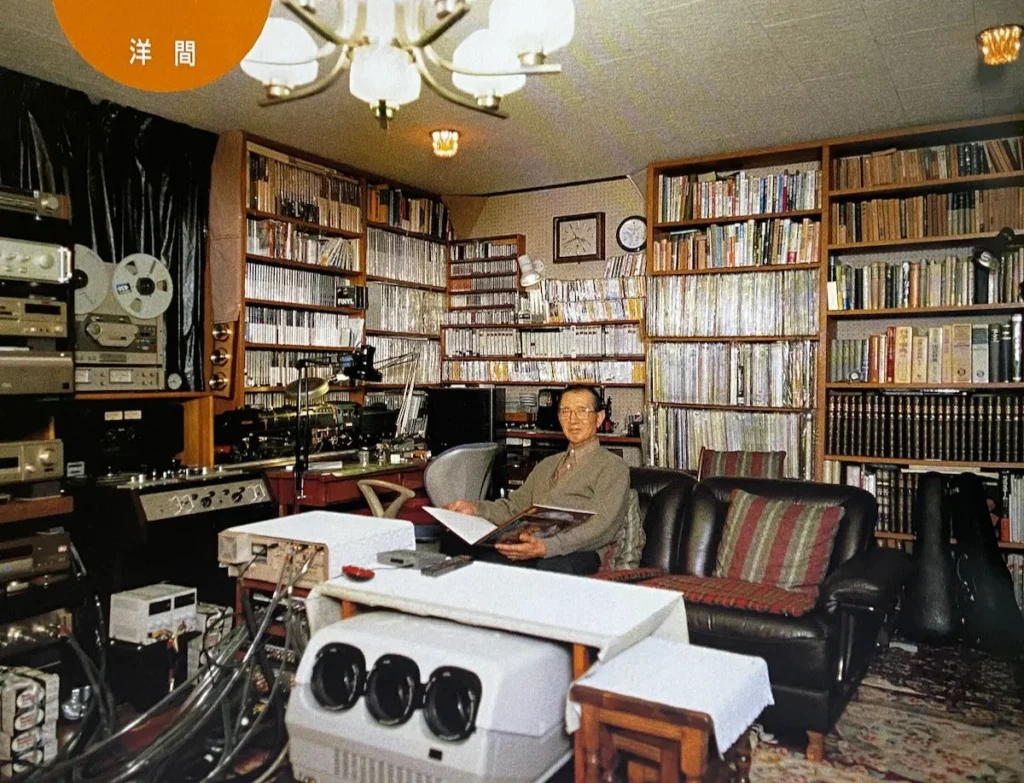

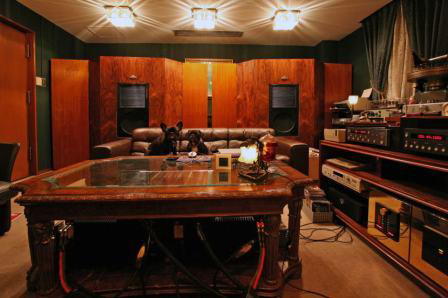

He, too, spent $40,000 on a custom installation that included new wiring and a circuit-breaker panel. He then claimed that his favorite classical music sounded “fresh and vivid, like they were playing in front of my eyes.” His wife, Reiko, reportedly heard no difference. “It’s completely beyond my understanding,” she said. “But if I take it away from him, he will lose the motivation to live.” This is in addition to assembling his own custom speakers, installing a noiseless air conditioner, and studying static and electromagnetic waves to better determine their effects on semiconductor performance, an ongoing obsession reportedly totaling roughly $351,000 over a 40-year span.

Meanwhile, Atsushi Hamasaki downgraded to a 250 sq ft apartment, avoided purchasing new clothes in 15 years, and the space taken up by his audio system meant he needed to move his couch to open his refrigerator, all in the pursuit of the perfect sound at home. Yoshihara, for his part, created his space with the hope of making it accessible for others to come and experience superior sound for themselves, reportedly hosting monthly listening sessions for a range of visitors that included composers and writers, “My happiness is for others to be happy,” he said.

Cases like Morita’s, Hamasaki’s, and Yoshihara’s are often circulated as proof of the lengths Japanese audiophiles are willing to go, and I decided to listen in to the culture of Japan’s extreme audiophiles as well as I could from a distance and attempt to understand this phenomenon a bit better.

The company that installed Morita’s pole reportedly erected roughly 40 other private utility poles across Japan in the span of ten years. But that was in 2016, and its unlikely that the number would have even doubled in the time since. In a metropolitan area the size of Tokyo with a population of 14 million, this suggests not a mass movement but a tiny, highly committed subset of listeners. All the more interesting to investigate.

To be sure, there is, notably, no definitive proof that private utility poles or surplus electricity produce measurable improvements in sound quality. Even within audiophile circles, these interventions sit at the far edge of plausibility. Online, reactions oscillate between admiration and parody.

One r/audiophile commenter dismissed Morita entirely: “He’s an amateur. From the video, and the way he breathes, I can tell his apartment is awash with normal air. I ensure my sound waves propagate through my own personal, untainted air which I have my audio scientist create from base elements and feed into my listening room through carefully selected tubes.” Though obviously satire, the comment reflects a shared logic taken to absurd conclusions, and it is a logic by no means limited to power supply.

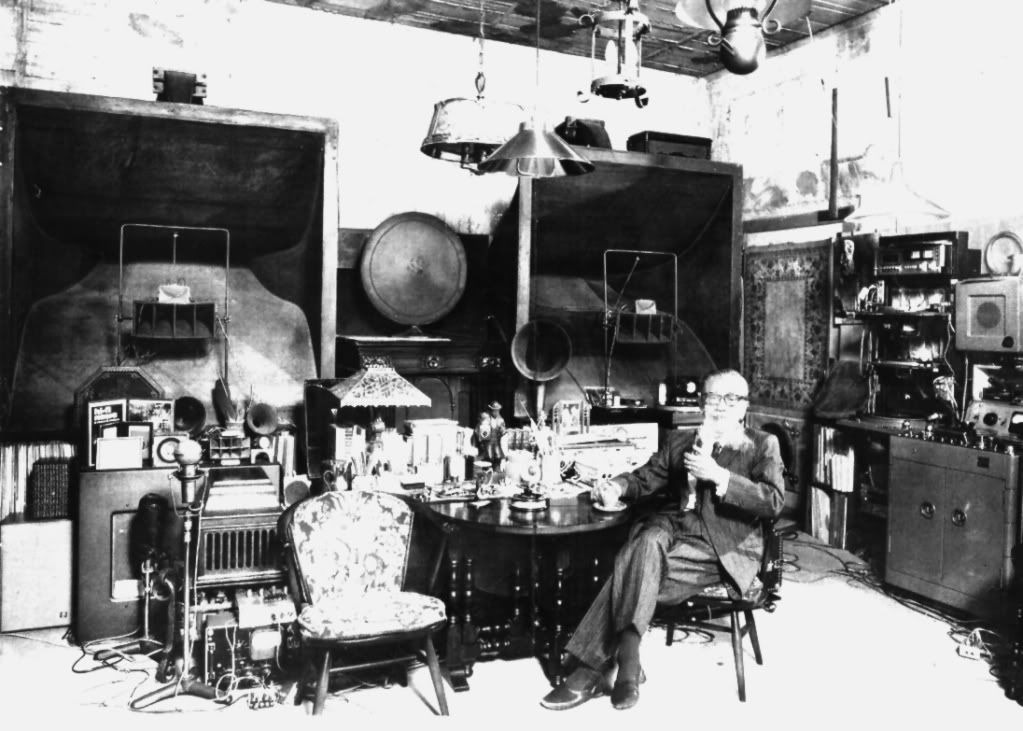

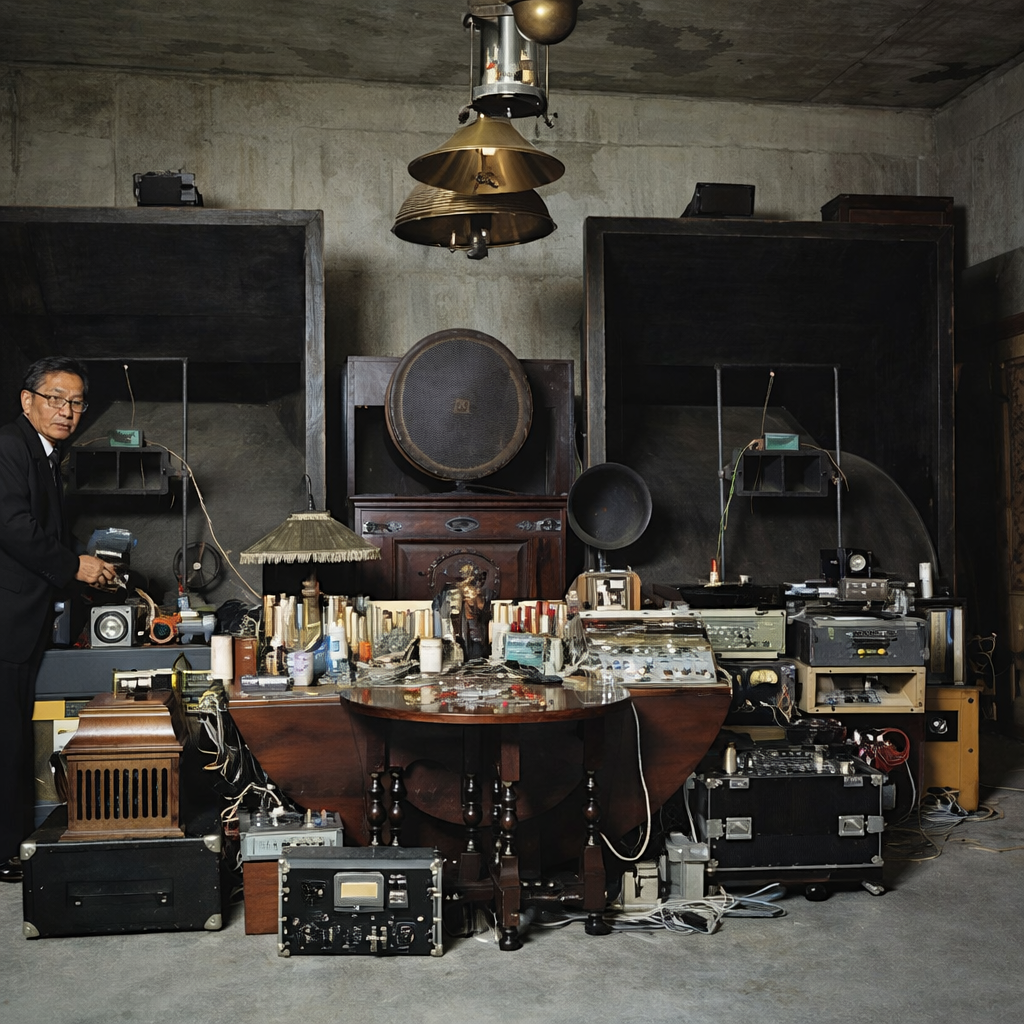

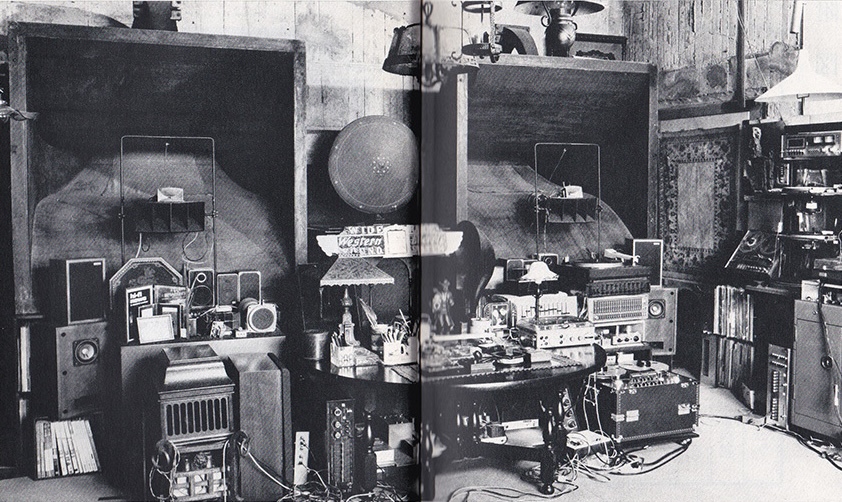

Turns out their approach to listening has a long legacy in Japan. One of the earliest documented examples of this movement was Kei Ikeda (1912–2001), an early audiophile who inherited a small fortune and put it towards his hobby, later becoming an engineer for JVC, pioneering stereo sound before it was widely adopted by the Japanese public.

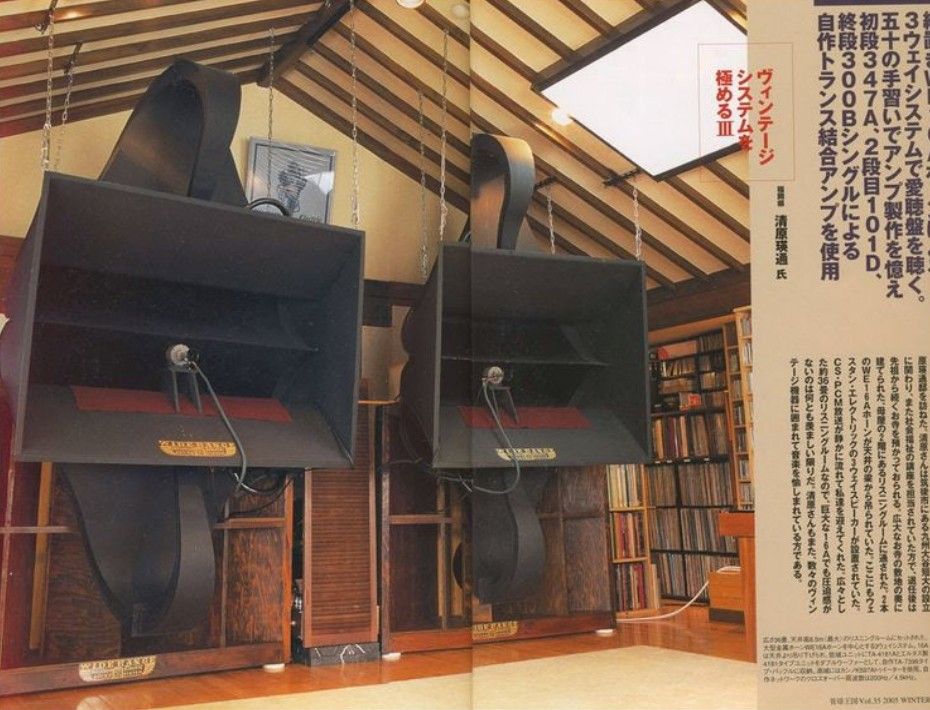

As early as the 1930s, his hi-fi setups used American technology from companies such as Western Electric, housed in a custom-built concrete auditorium where the architecture itself became part of the acoustic setup, a sight to see for anyone who might have met him and almost certainly laying down the expectations for today’s Japanese audiophiles. Even today, however, Ikeda’s approach represents an outlier rather than a norm, although his mindset is quite understandable to many other people in Japan.

This is because the philosophical roots of this subculture lie deeper than individual eccentricity. Japan developed a listening culture shaped by scarcity and concentration that really blossomed after the end of World War II. Jazz kissa, or hi-fi listening bars, emerged in the years following the war, when imported records were prohibitively expensive and rare. Whereas other countries with such scarcity resorted to making cheap copies and listening using whatever means were available, listeners in Japan turned their hobby into a communal event, ensuring the best possible sound, even if it meant it needed to be shared.

For many people, these cafés were the only places to hear music from abroad, and since so many people would be gathered in one room, the emphasis was on silent, attentive listening, so as not to ruin the experience for anyone else. Sound was not background; it was the event.

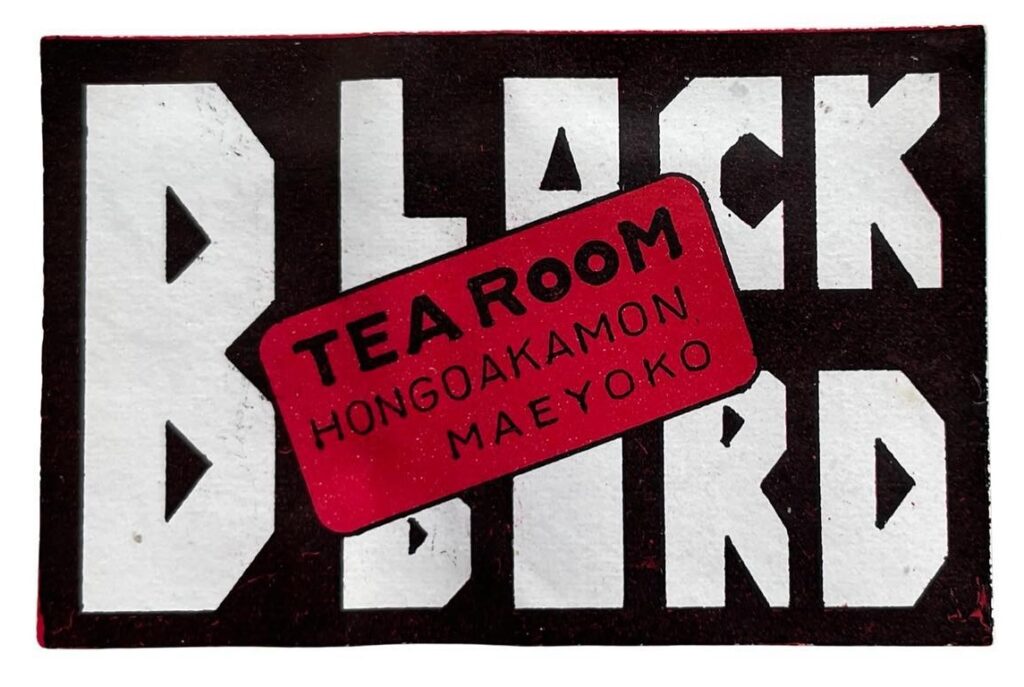

Jazz kissas, a purely Japanese invention, actually began as early as the late 1920s with the opening of places like Shibuya’s Café Lion (continually run since 1926) as well as the Blackbird Tea Room, which opened in 1929 near the University of Tokyo, attracting listeners inspired by American jazz arriving on cruise ships in ports such as Yokohama and eager to hear more. Jazz was banned during World War II, only to return even stronger after the war when U.S. servicemen brought records from the States.

For a time, the kissas were the center of Japan’s very serious listening culture. Dug, a famous jazz listening bar in Tokyo’s Shinjuku District, was known to play albums while its listeners sat motionless, heads bowed, as if attending a monastic ritual, with lights dimmed and windows taped up to ensure maximum focus. Many remarked that the patrons seemed as if they were all deep asleep, including the police, who showed up to investigate why so many people were gathered in a suspiciously dark room.

Many of the surviving bars continue this atmosphere, often strictly forbidding any speaking or phone use inside the premises. With the widespread availability of home audio tech and growing consumer market, the kissas began to decline during the 60s and 70s as audiophiles took their hobby to the comfort of their own homes.

Today, the opposite has happened, as a shrinking economy has made such products unaffordable to Japan’s younger generations and have once again led to a boost in communal listening, even exporting the kissa format abroad to places such as Hong Kong and New York.

While traditionally focused on jazz, Brazilian, orchestral, and funk genres, the kissa has evolved over the decades. Modern Tokyo’s dense ecosystem of small listening bars and genre-specific clubs, from hip hop to drone to post-punk, extends this tradition and aligns with sociologist Ray Oldenburg’s idea of “The Third Place,” spaces that are neither home nor work but culturally essential, an idea that is enjoying a renewed focus today. The audiophiles that would take the time to get the right equipment and install their own power sources are themselves on the decline now, as they are almost exclusively retirees who have the time and money to afford these luxuries.

The Japanese audiophile market is highly varied in its aims and preferences, but most participants stop well short of installing personal power grids. The same applies to the preference of historical (some would say antique) equipment, although its still enough to make waves across the world.

Among enthusiast discussions, many have noted that Japanese collectors have driven up prices specifically for 1930s Western Electric amplifiers, old cinema horn speakers the size of refrigerators, and vacuum tubes originally designed for telephone exchanges, believing that pre-war industrial components possess a lost integrity or “soul.” This is a cultural preference nearly a century in the making, but its a language not well understood by the uninitiated.

With all this mind, what emerges is not a portrait of Japanese music consumers as a whole, but of a distinct subculture that is highly visible, deeply committed, numerically tiny, and getting older by the day. 40–80 utility poles in a country of over 120 million people do not indicate a mass movement, but they do indicate one particular strategy of a wider group for whom the pursuit of perfect sound justifies extraordinary measures. Whether these listeners are pioneers pushing the limits of perception, or simply practitioners of a beautifully elaborate faith, depends largely on what one believes sound is capable of carrying.