A new auction unearths classic works from Raymond Pettibon, frequent Black Flag collaborator and the foremost artist of the Southern California hardcore punk scene of the 80s.

In 1982, Black Flag sang the words “I was a hippie, I was a burnout, I was a dropout, I was out of my head, I was a surfer, I had a skateboard, I was so heavy man, I lived on the strand, I was so wasted” If that doesn’t illustrate a vivid picture of the SoCal hardcore punk scene, nothing does—except maybe the actual illustrations.

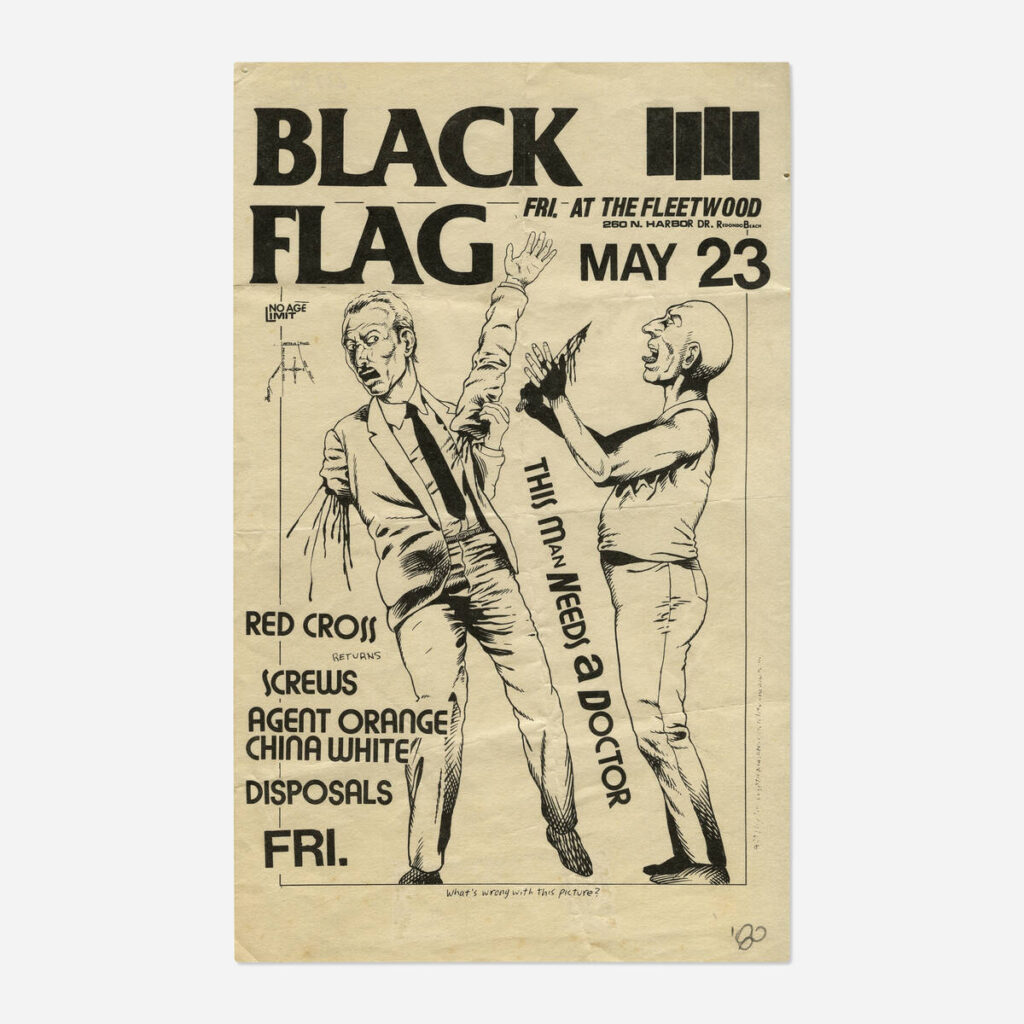

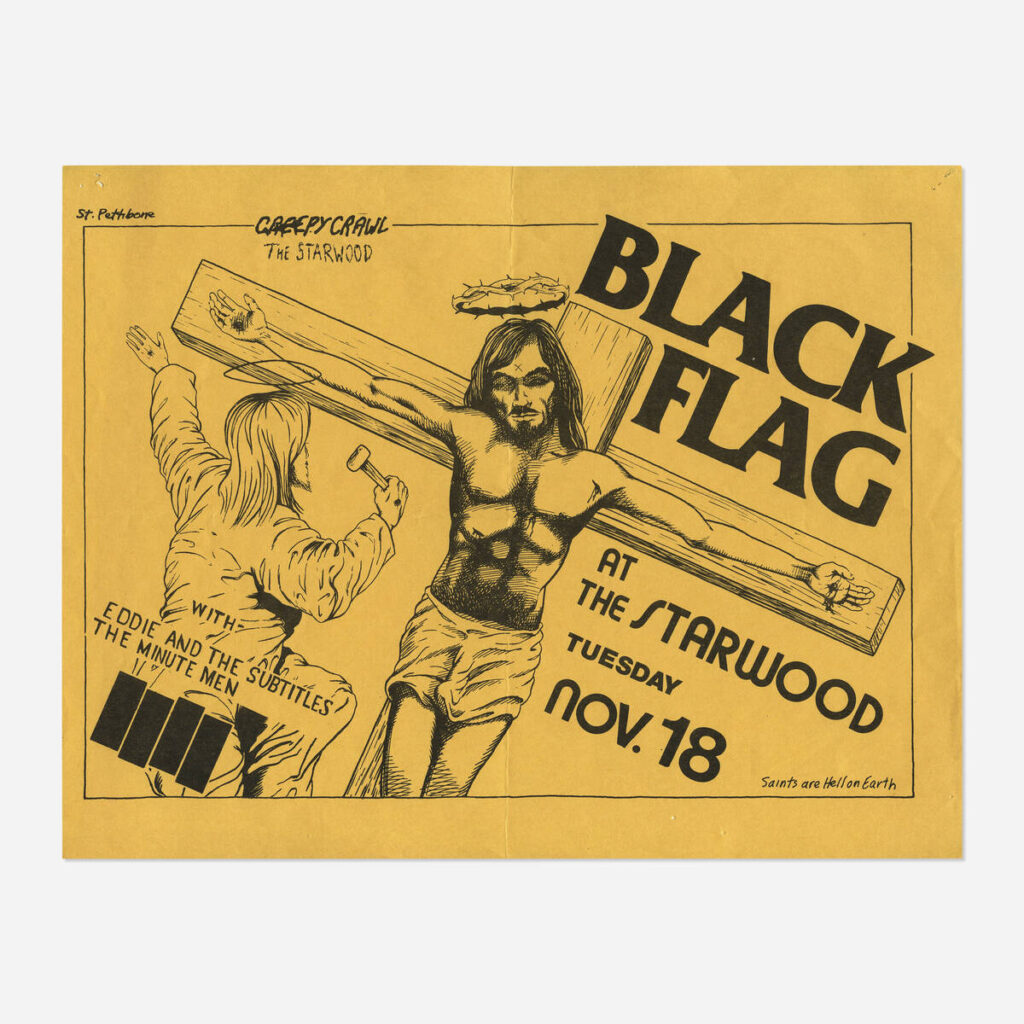

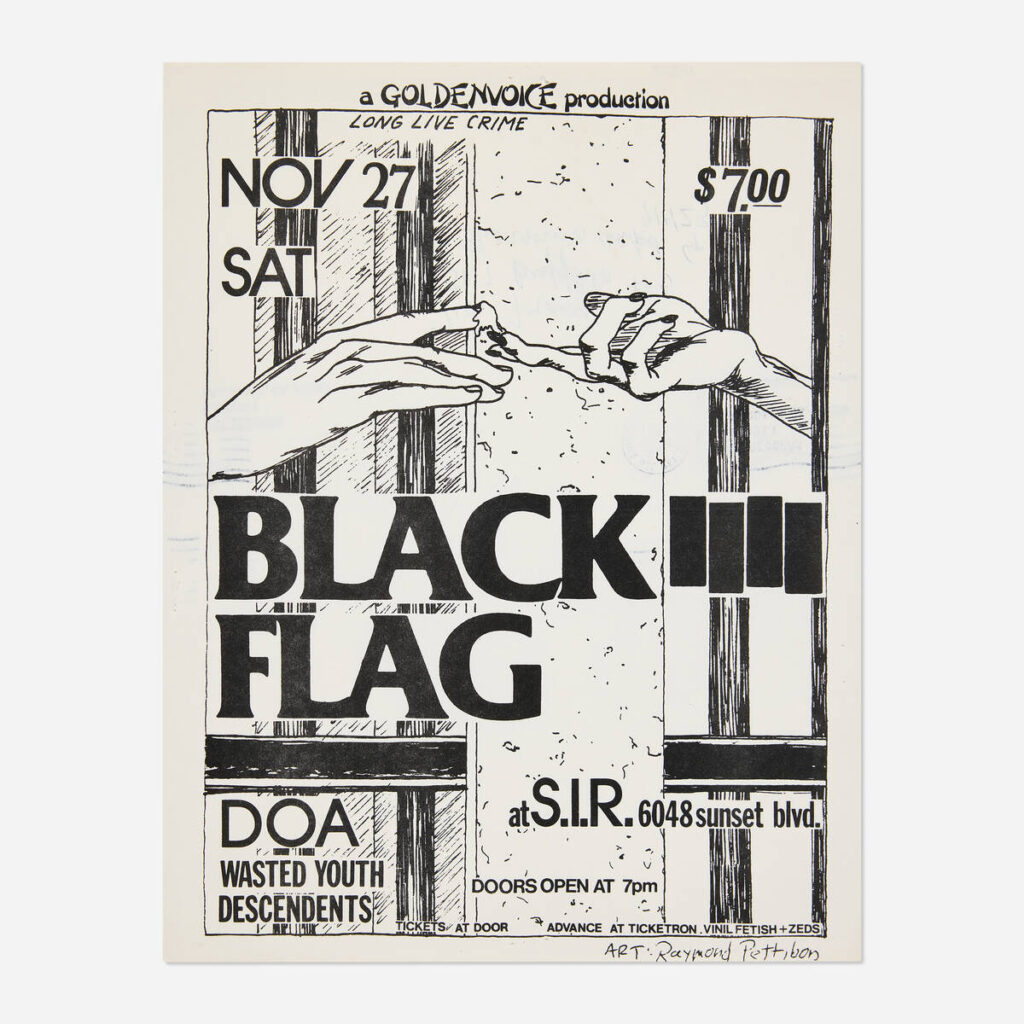

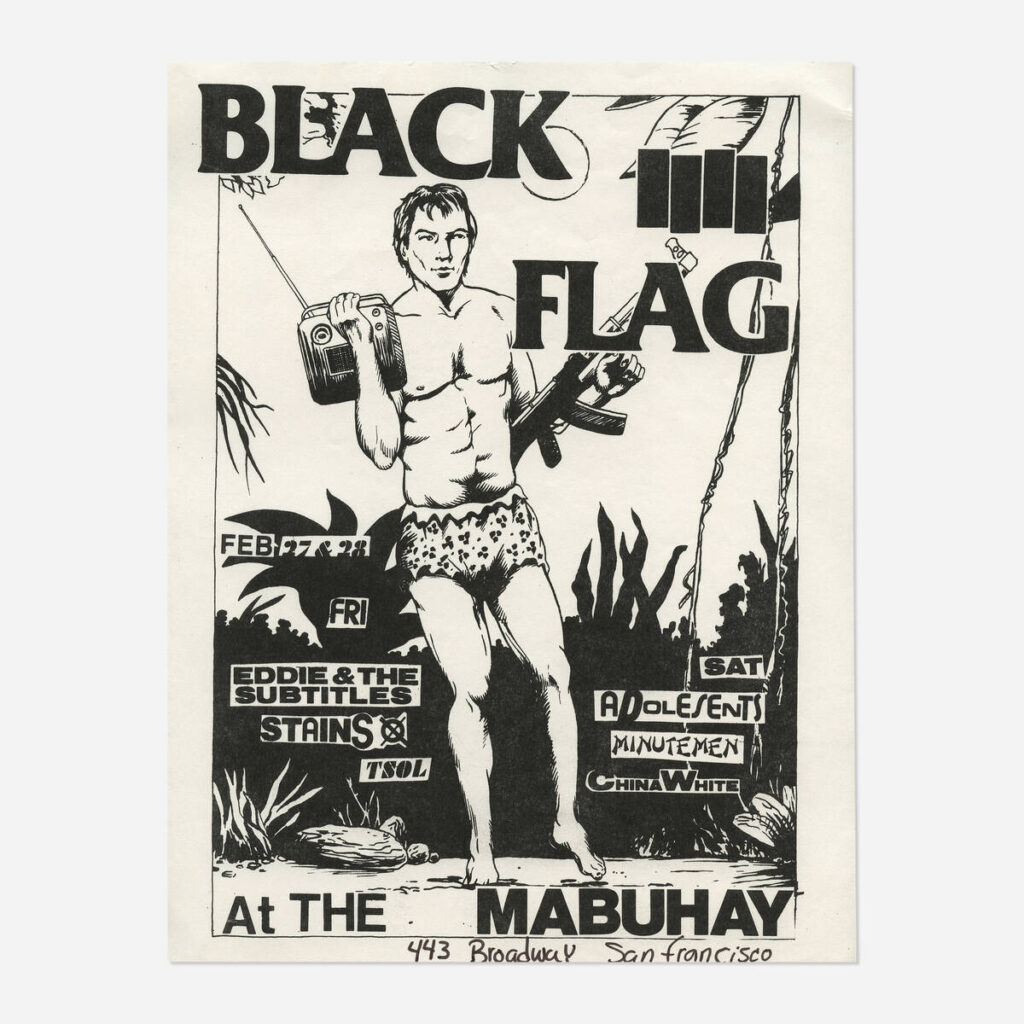

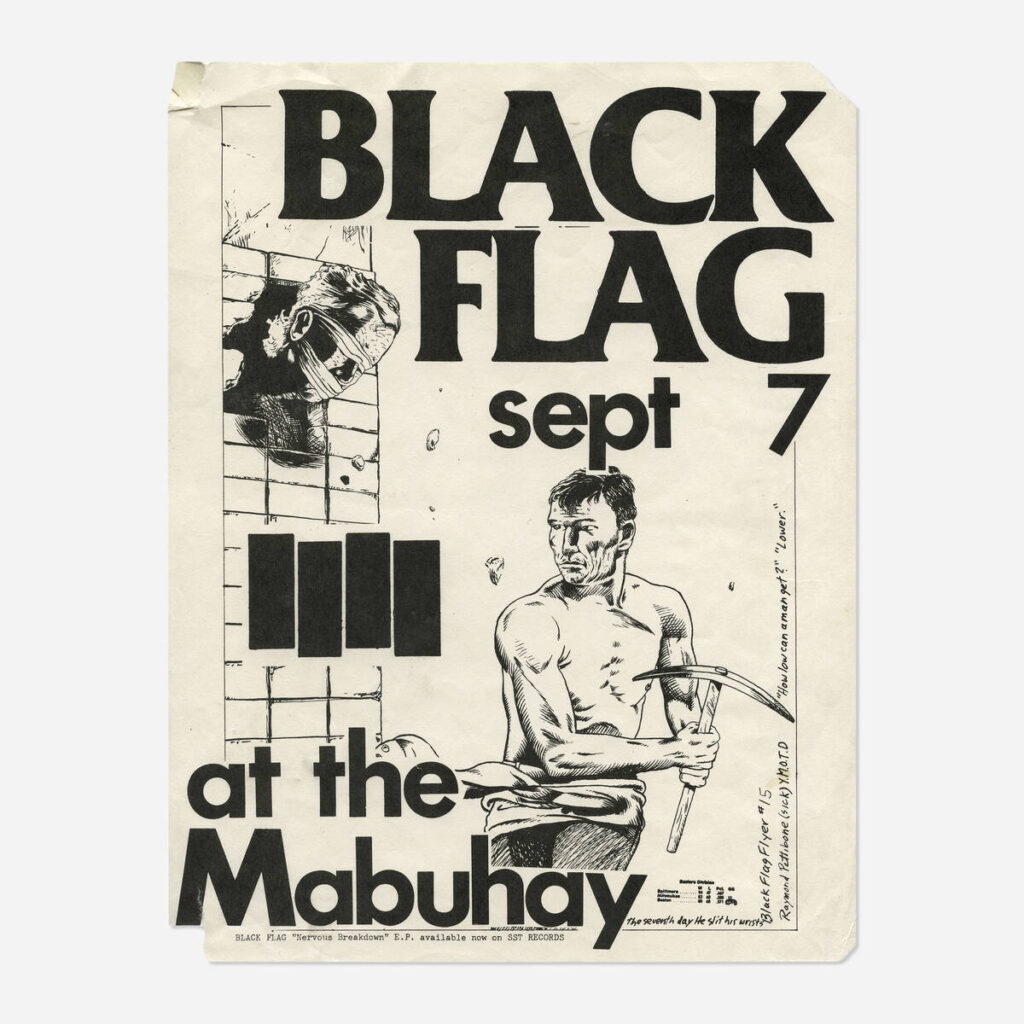

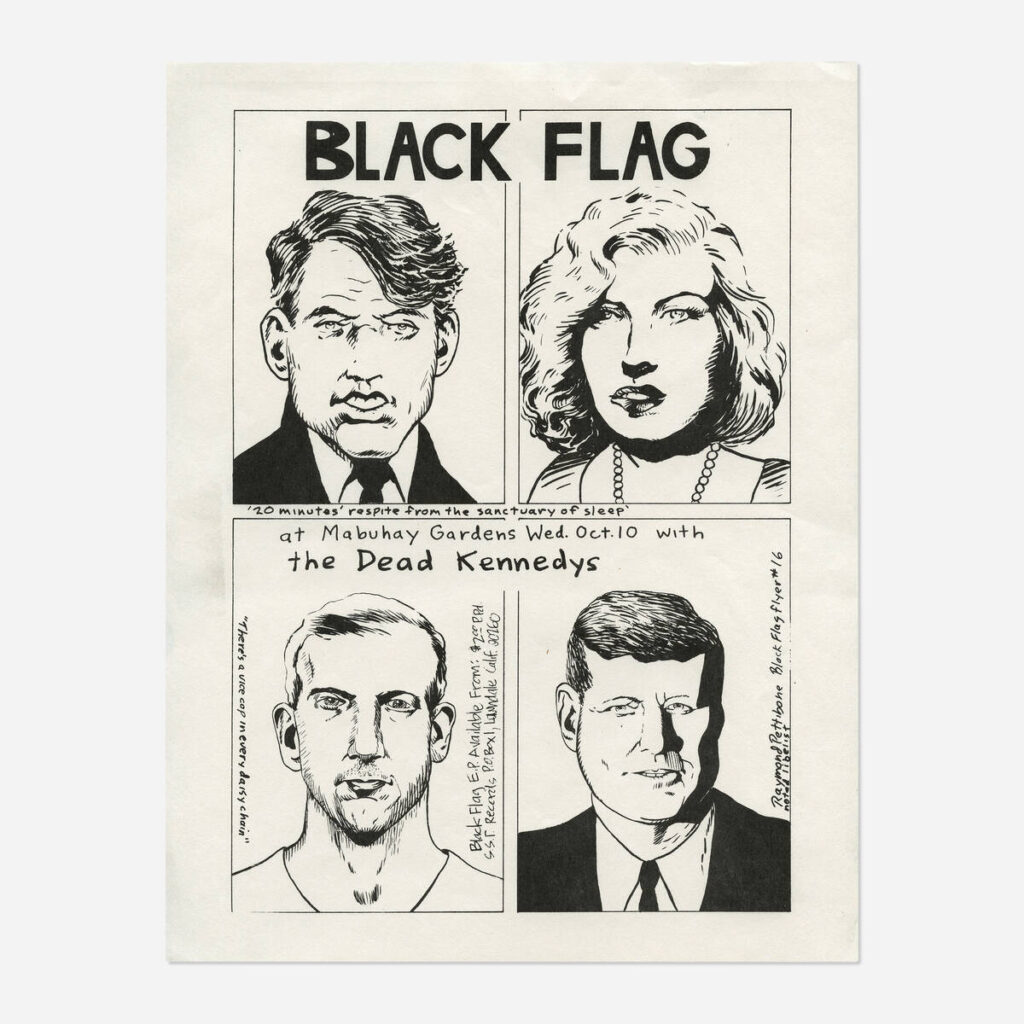

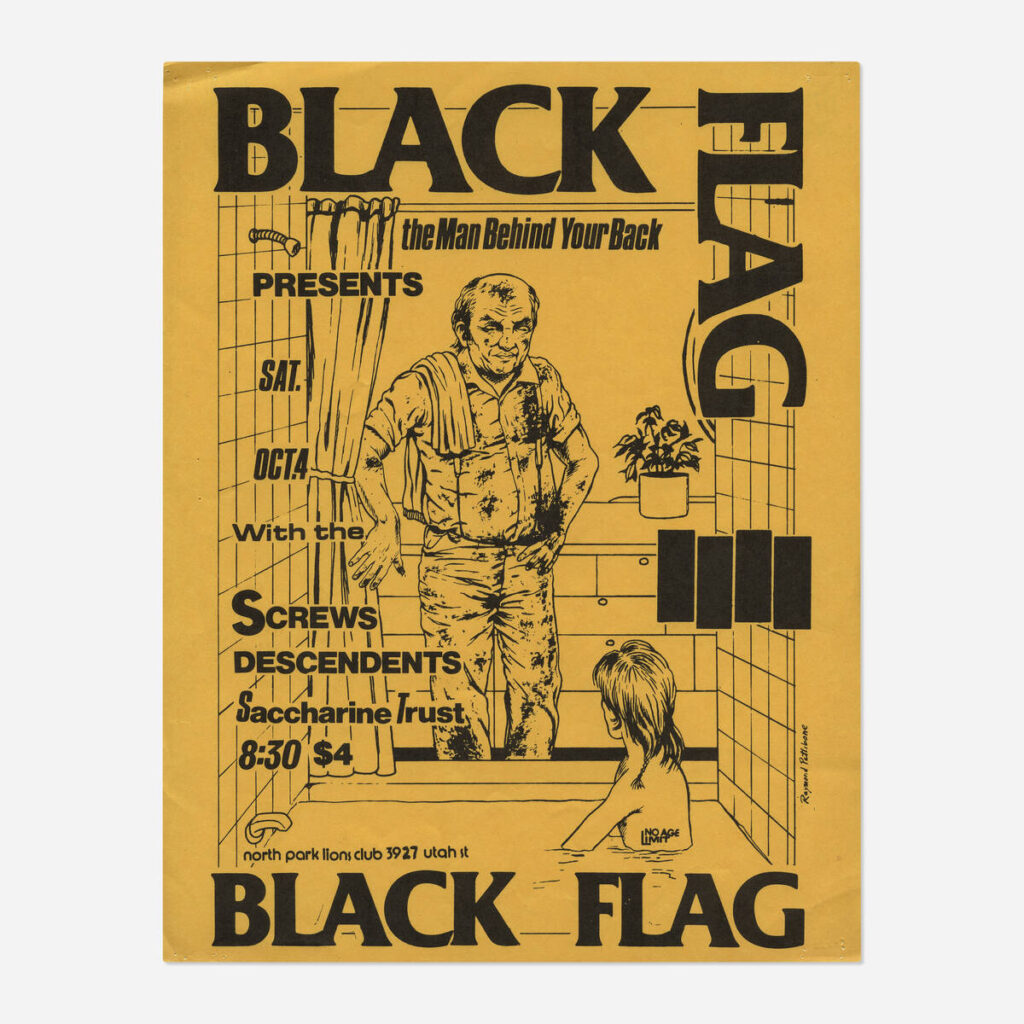

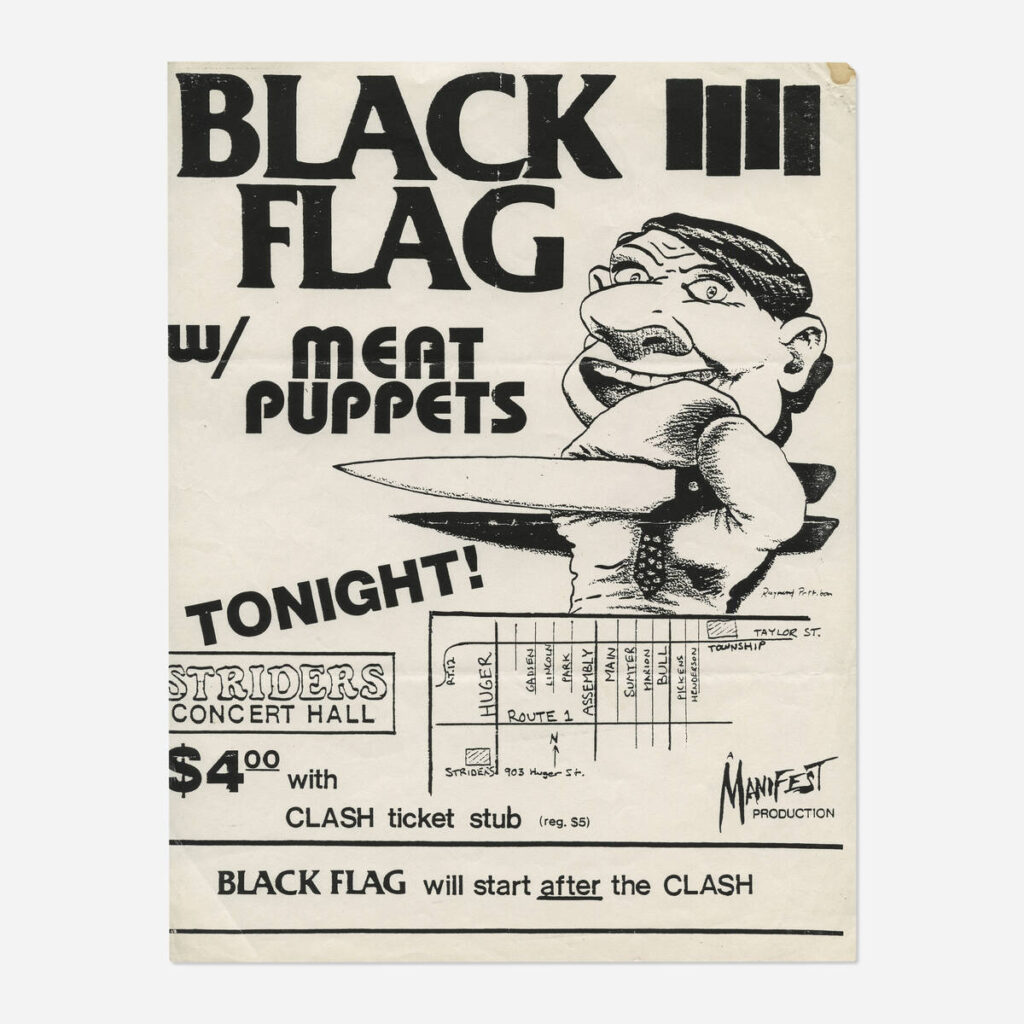

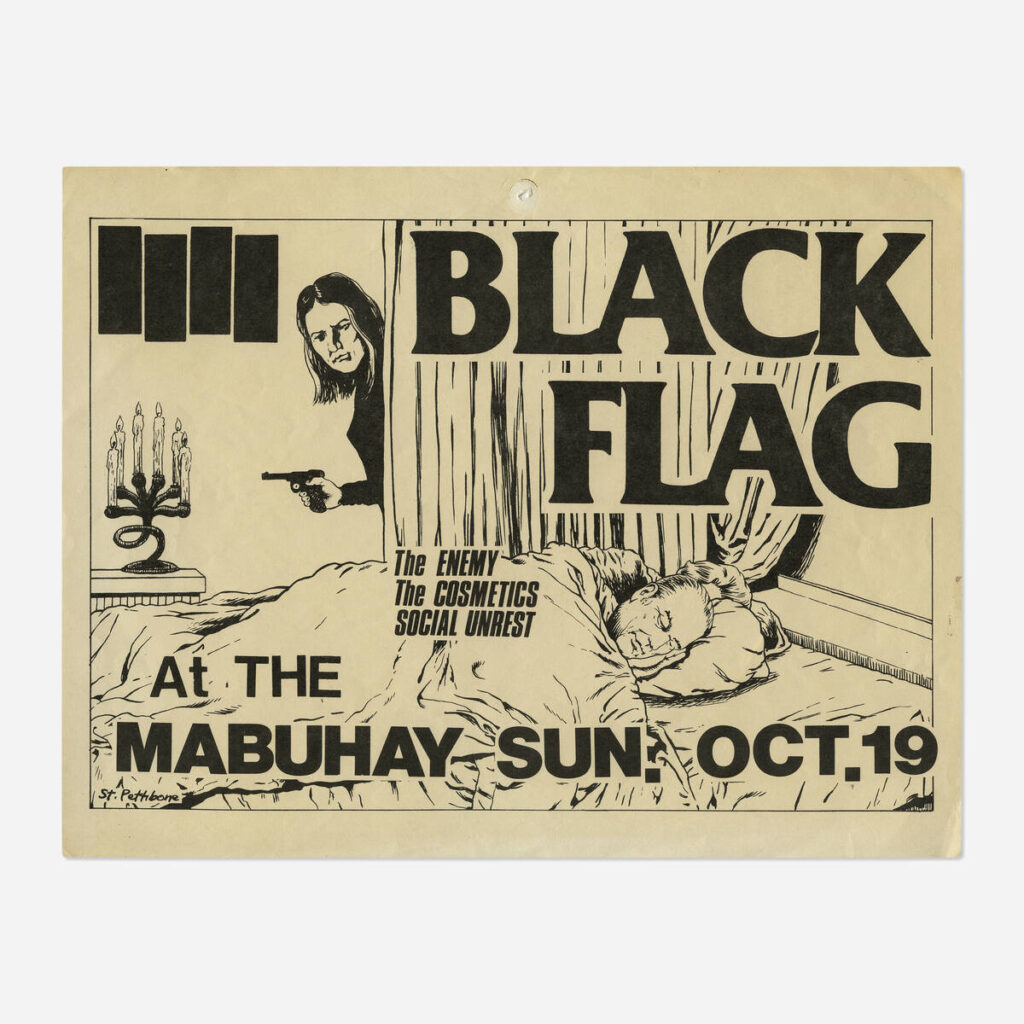

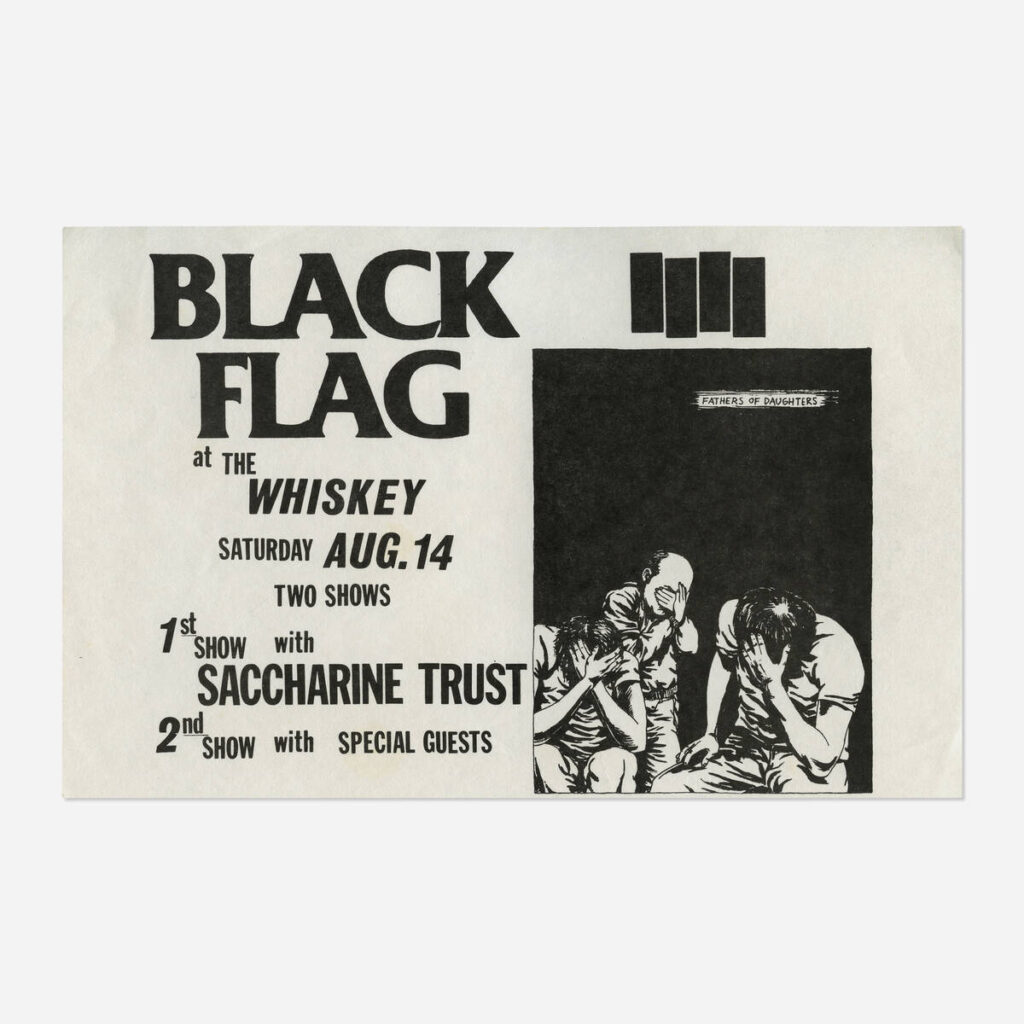

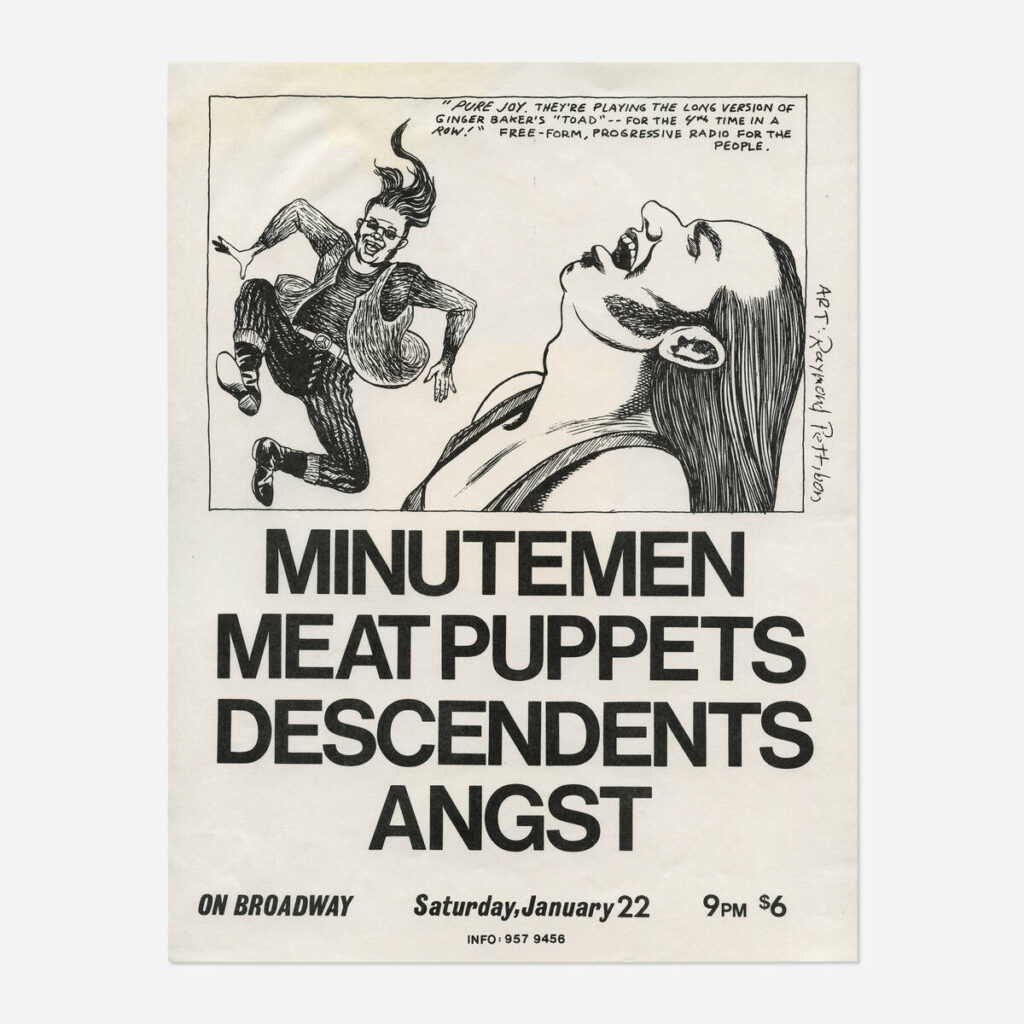

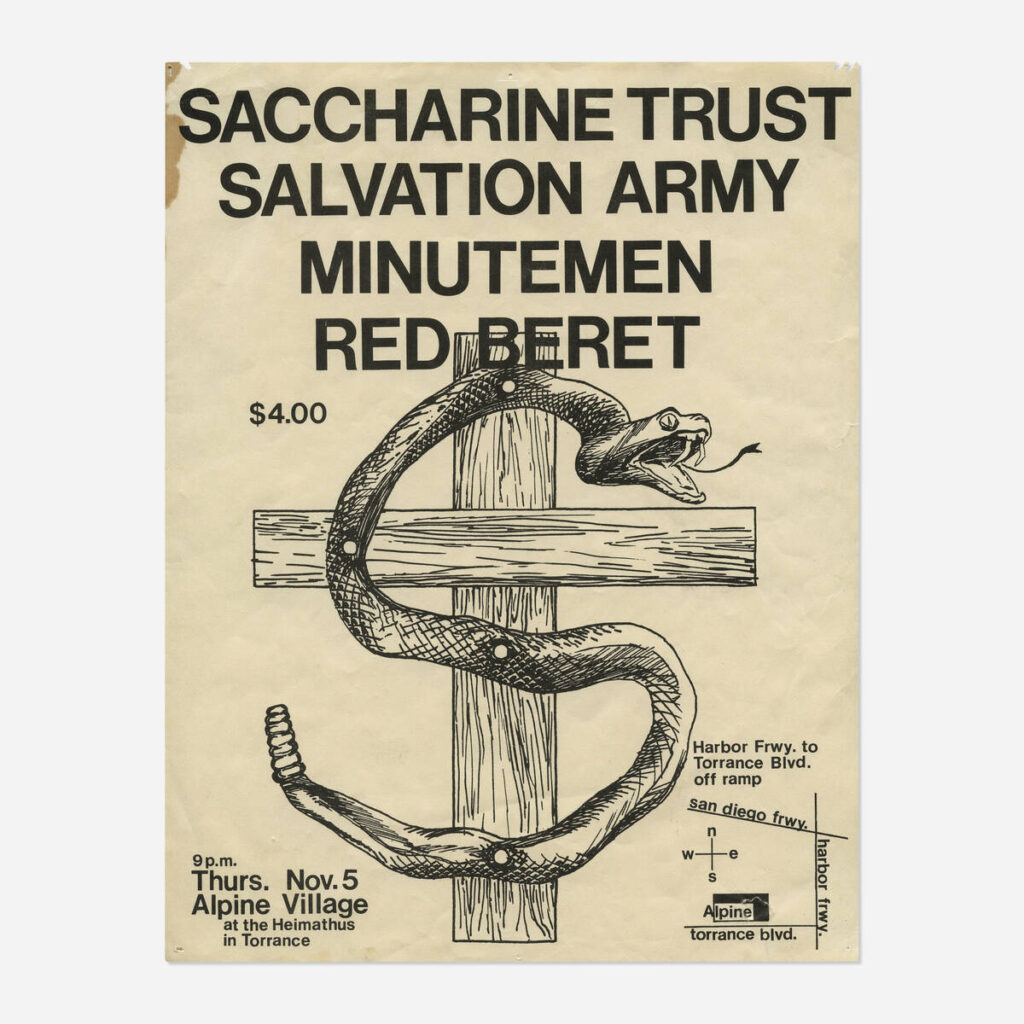

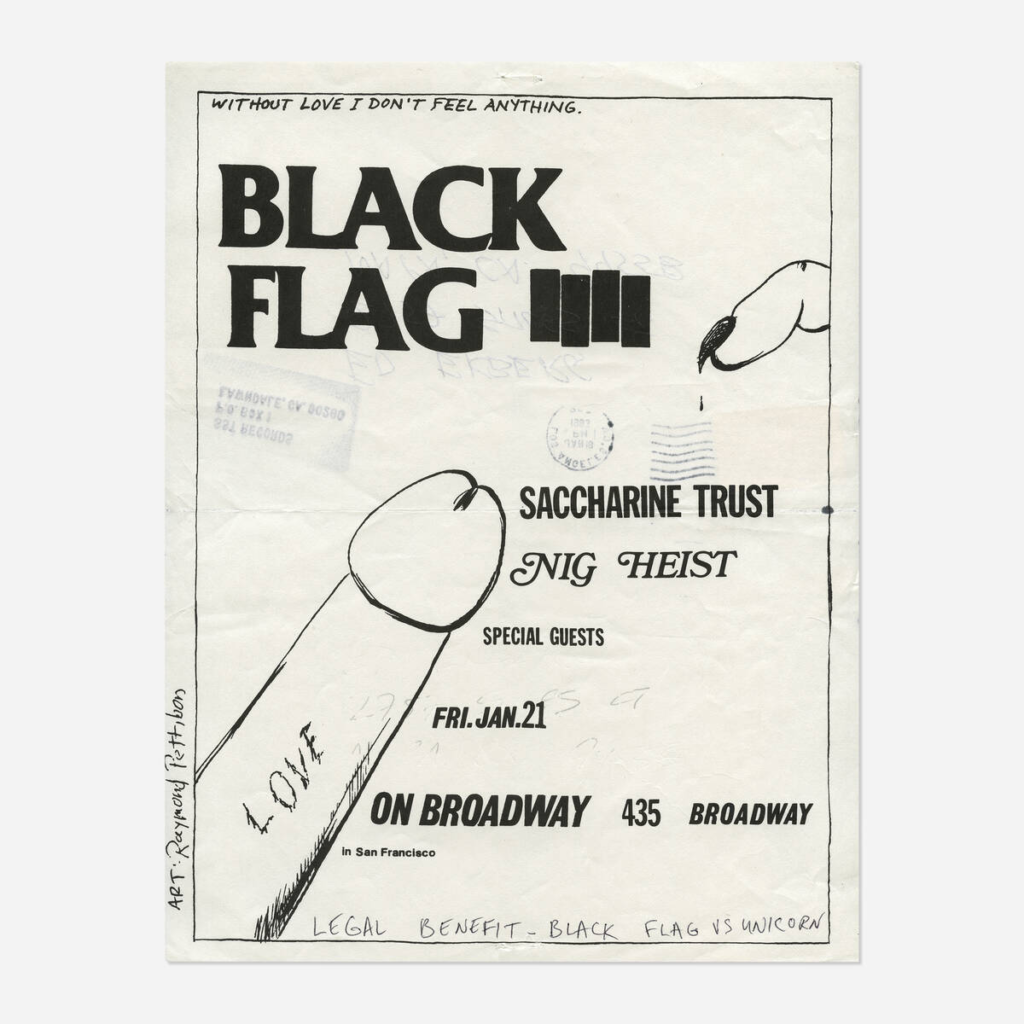

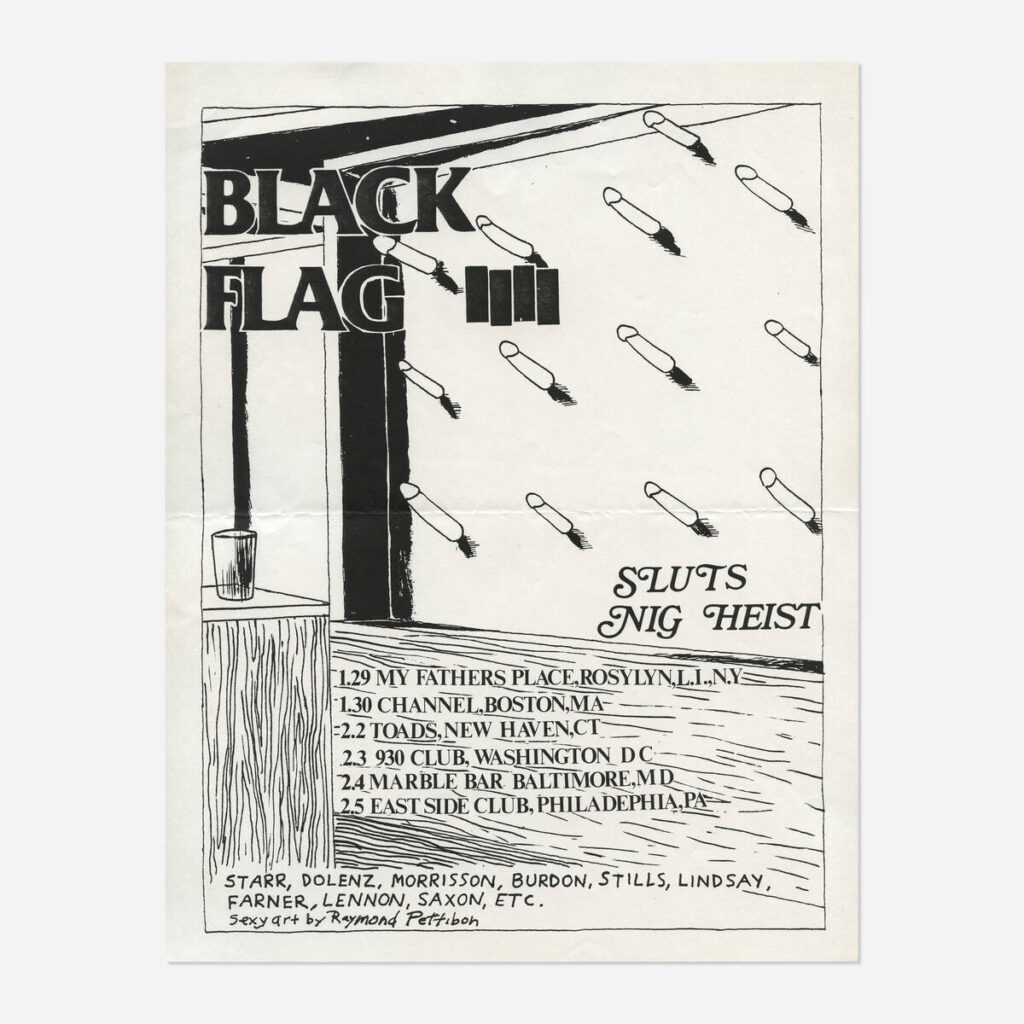

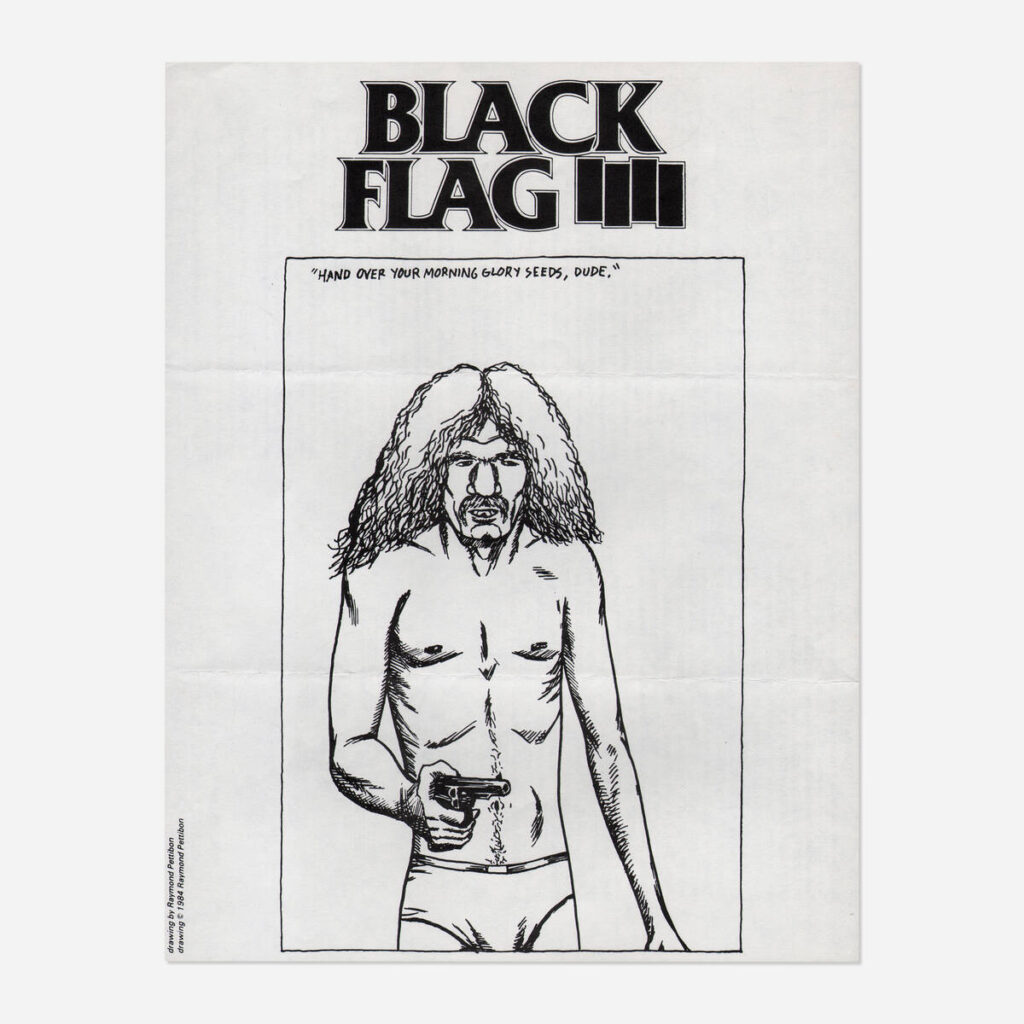

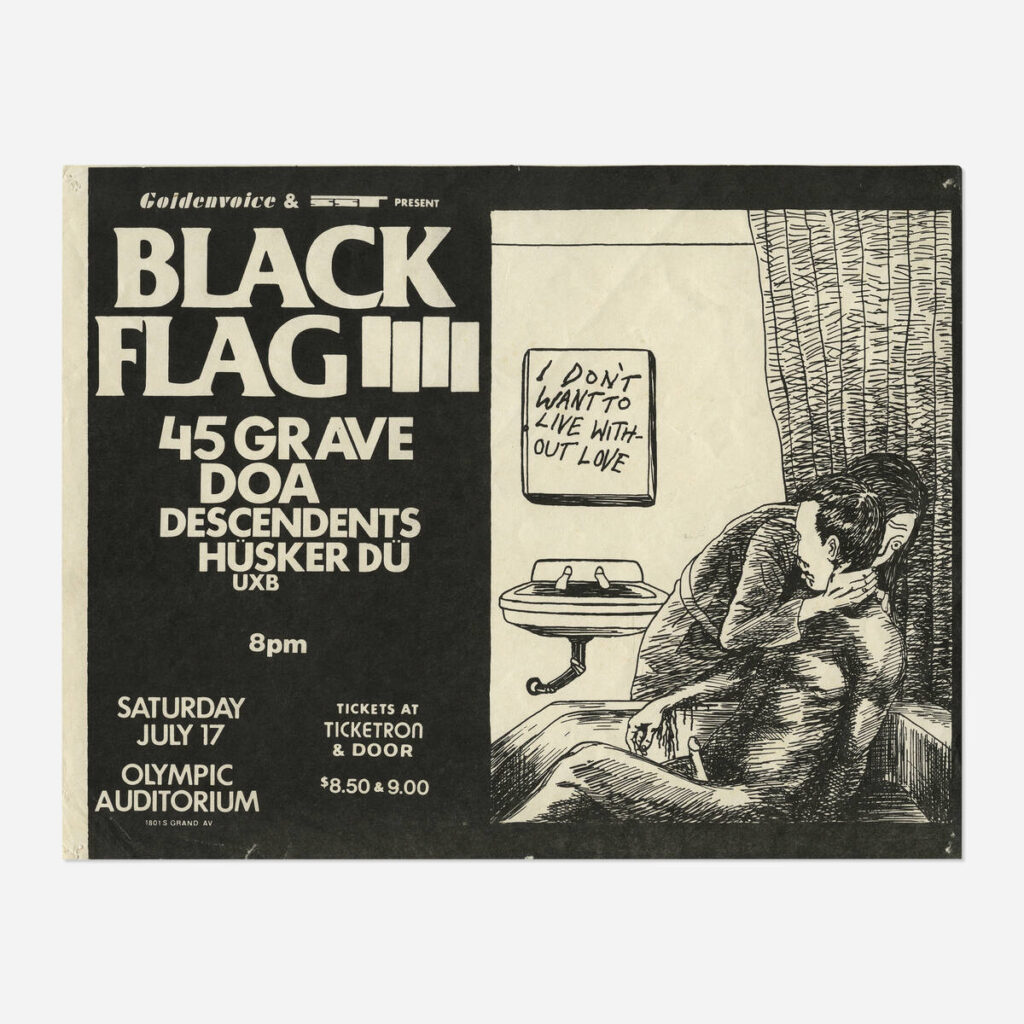

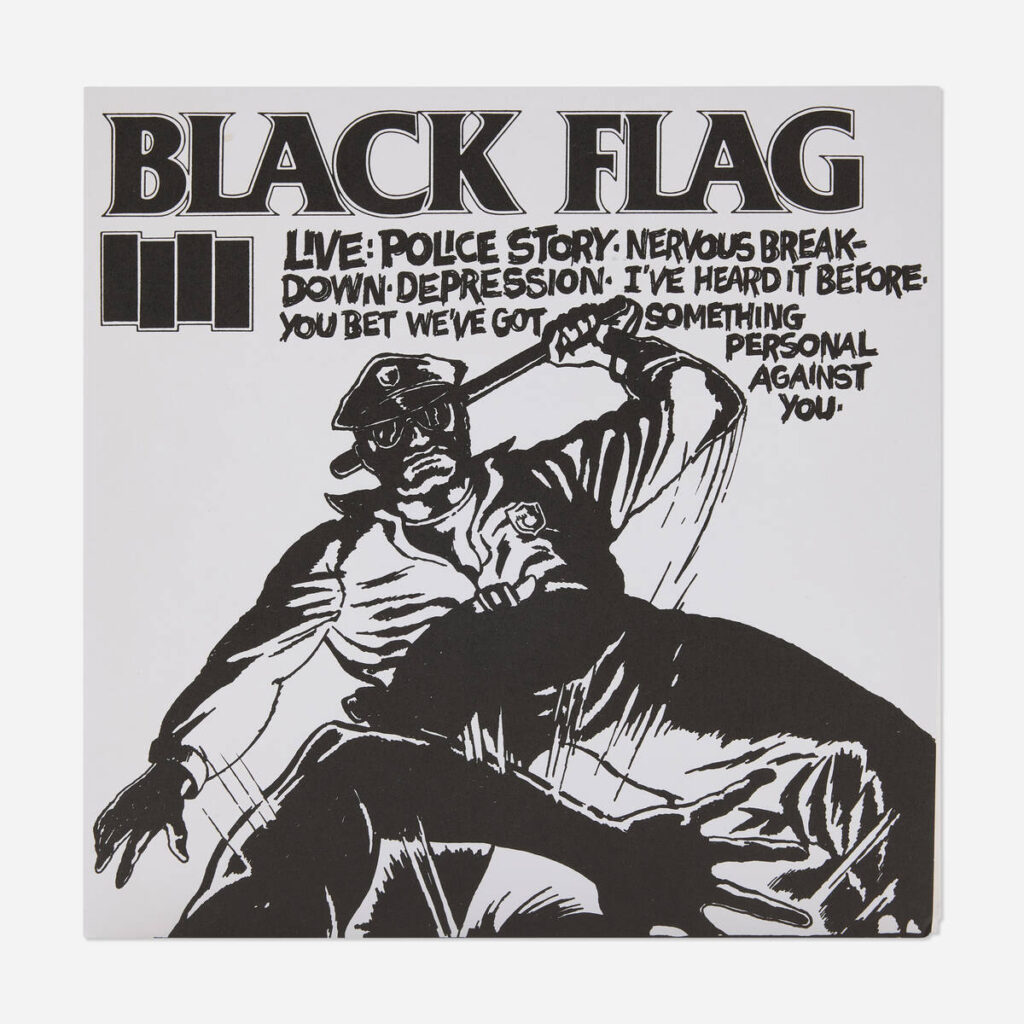

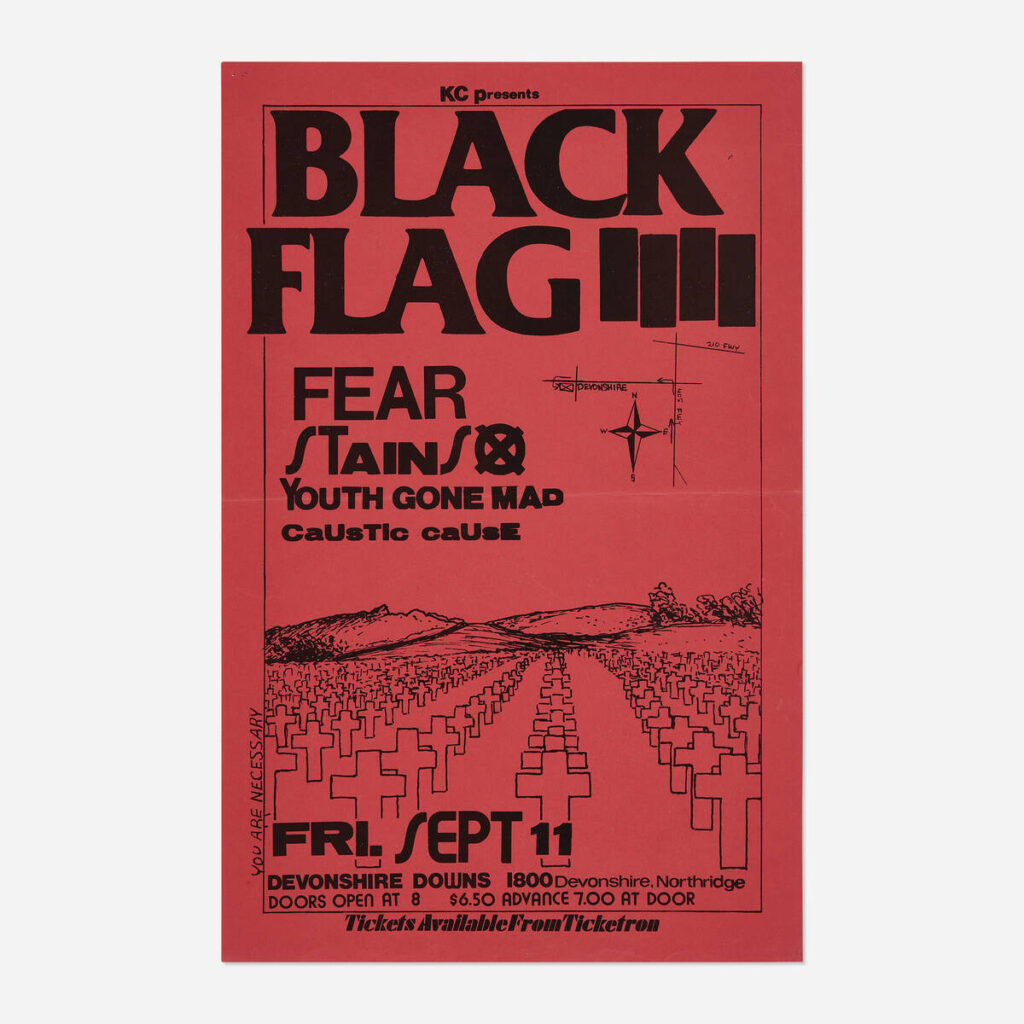

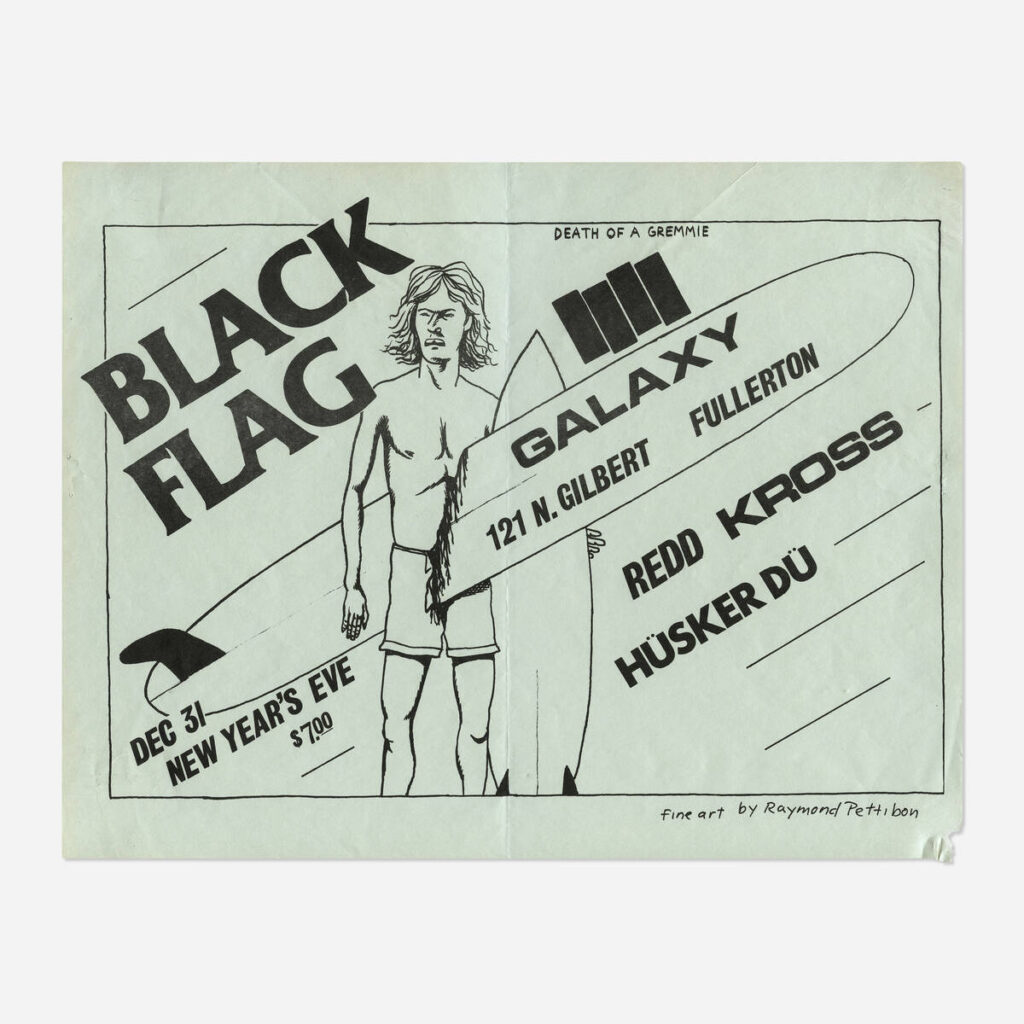

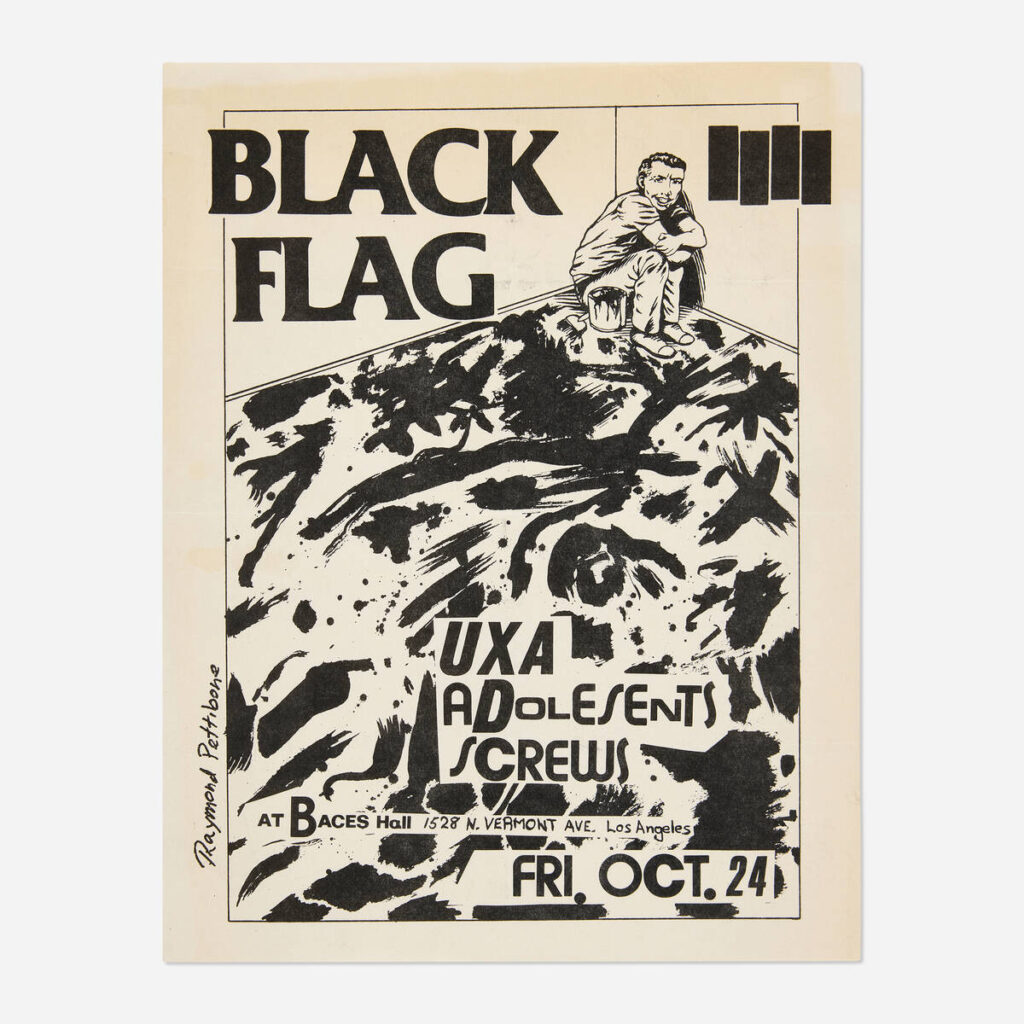

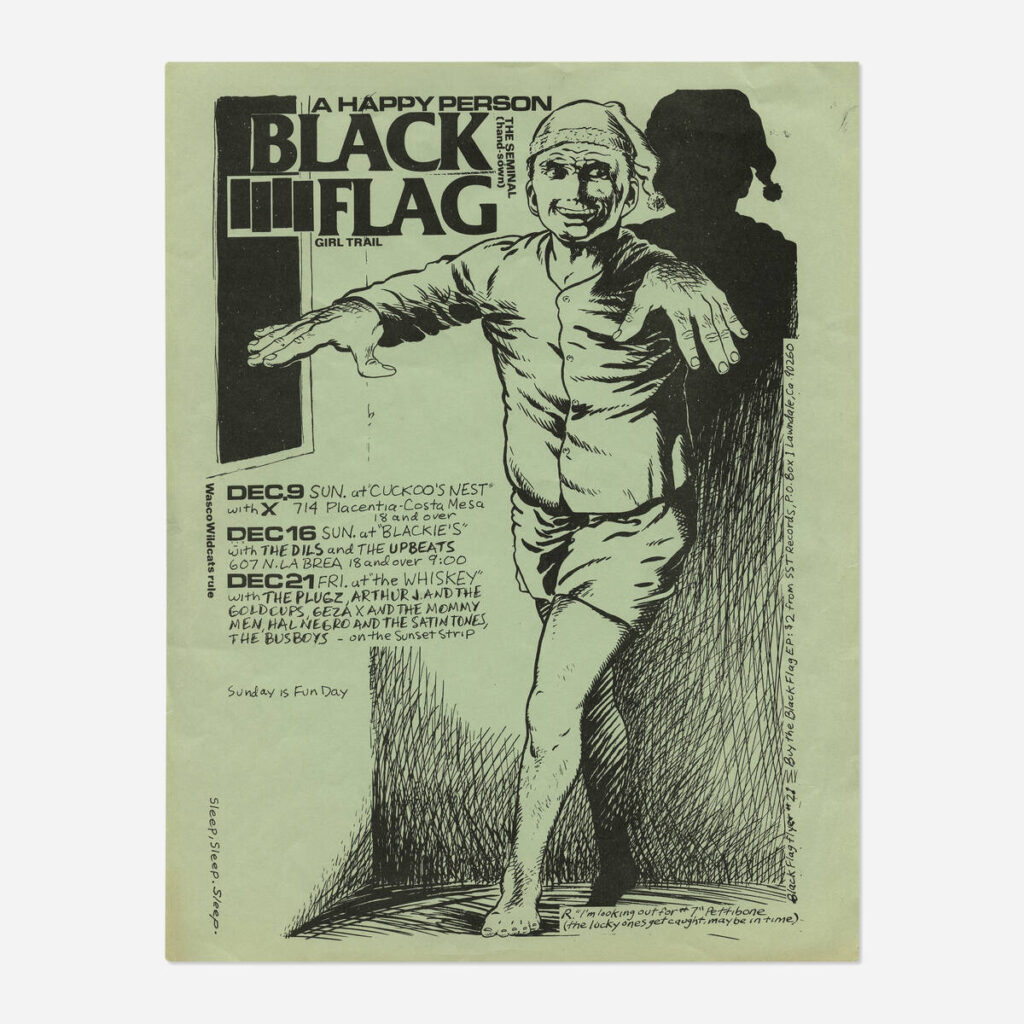

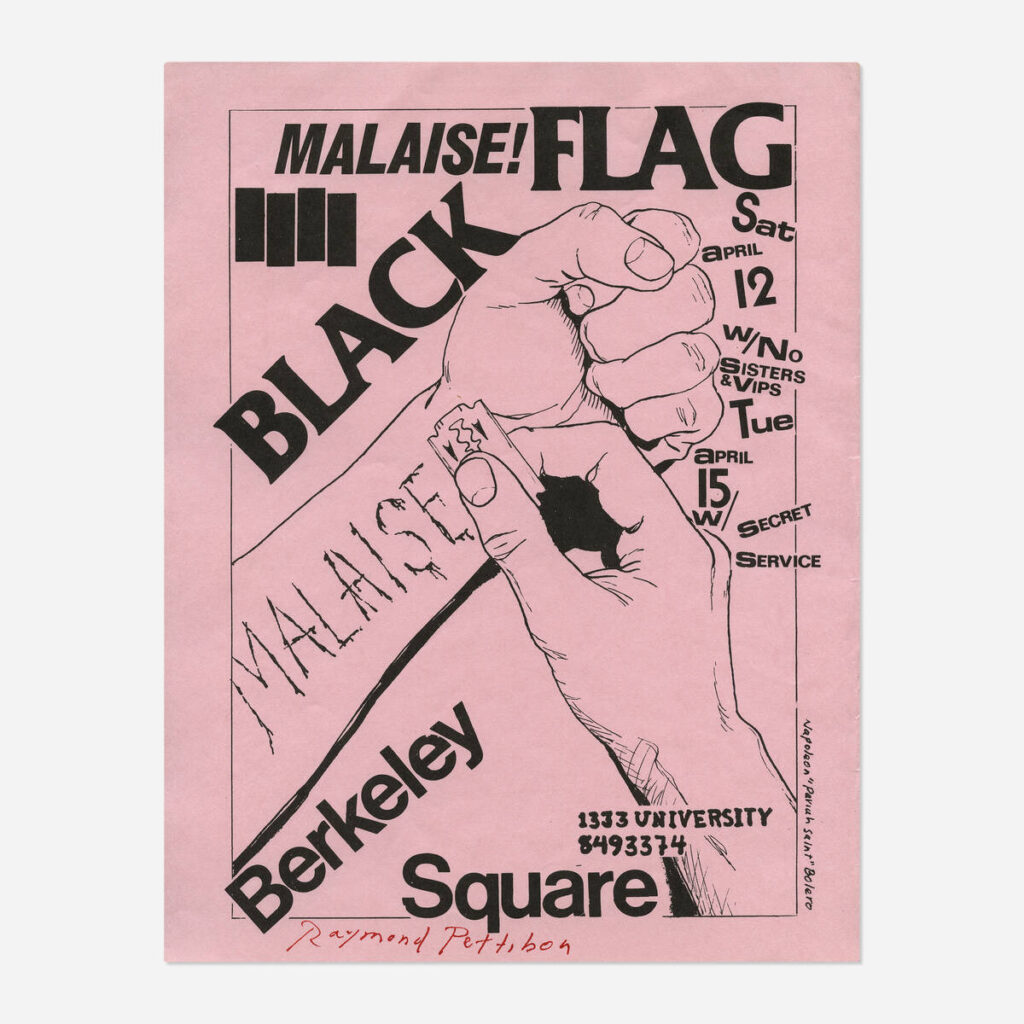

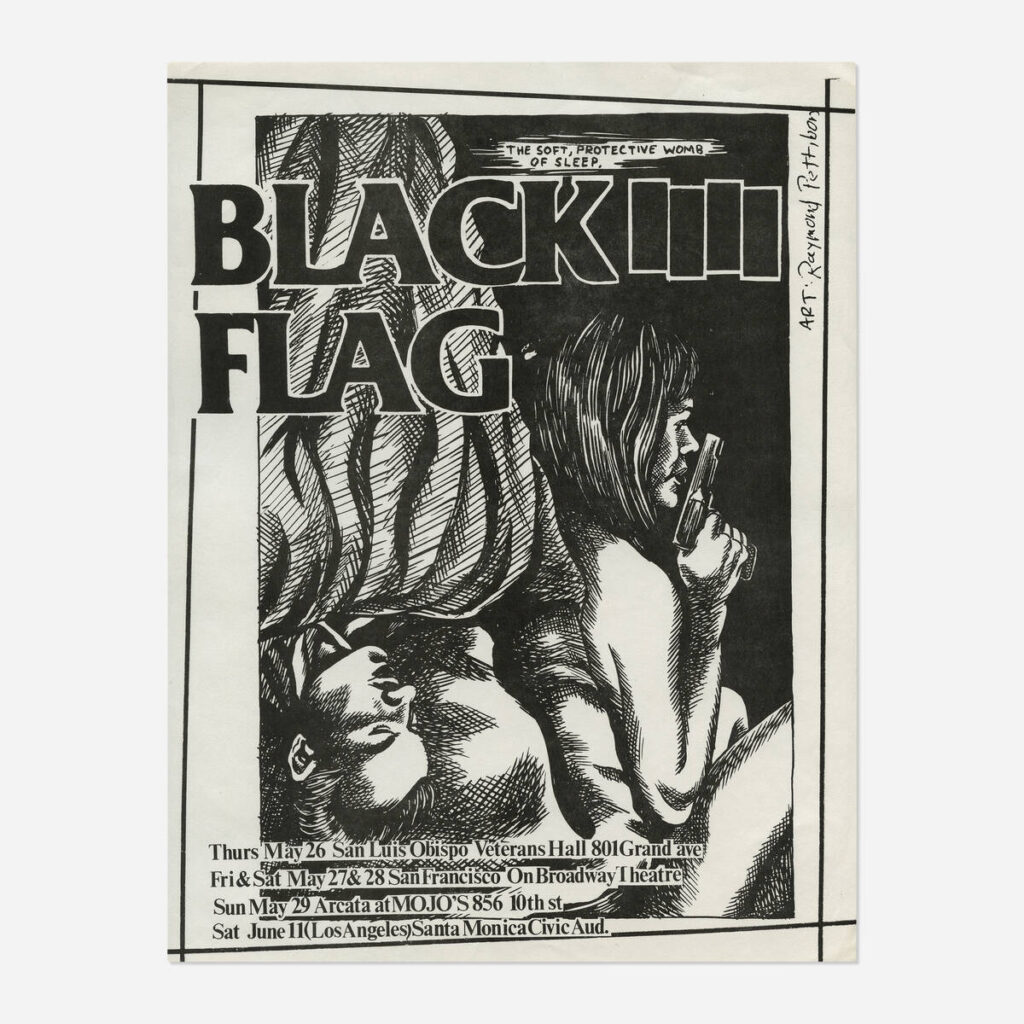

Even if you don’t know anything about hardcore punk music from California, you’ve almost certainly heard of Black Flag. If so, you’re even more certain to have seen the flyers for their shows back in the day, whose provocative and crass style defined the 80’s southern California scene back in the day. The man behind those flyers has a name, Raymond Pettibon, the brother of one of Black Flag’s members and the band’s quasi-official artist from 1978 to 1986 (he even came up with the band’s name and distinctive logo).

Today I found out there’s a major auction going for some of the art from back in the day. Flyers and whatnot that have laid undisturbed for decades are now for sale and going for surprisingly very democratic prices on the net (average starting bid on a flyer or zine is just $50), courtesy of Chicago’s Wright Auction House and LA Modern. And if you’re broke and can’t afford to bid on art, I’m right there with you, but it’s a great opportunity for us to get a good look at some history before some collector reliving his glory days snags it all.

Despite having no art education or real experience other than drawing some political cartoons when he was much younger, Pettibon’s collaborations with Black Flag were incredibly prolific, having sprouted from the fertile soil of disaffected youth.

Each show’s flyer was, they say, printed at least 500 times and distributed in as many places around town as possible. Despite all that, not a lot of them seemed to have survived (80% are estimated to have been destroyed), and a single one often goes for several hundred dollars at auction, which is what makes this particular event so interesting. Ironically, Pettibon himself was working basically for free at the time.

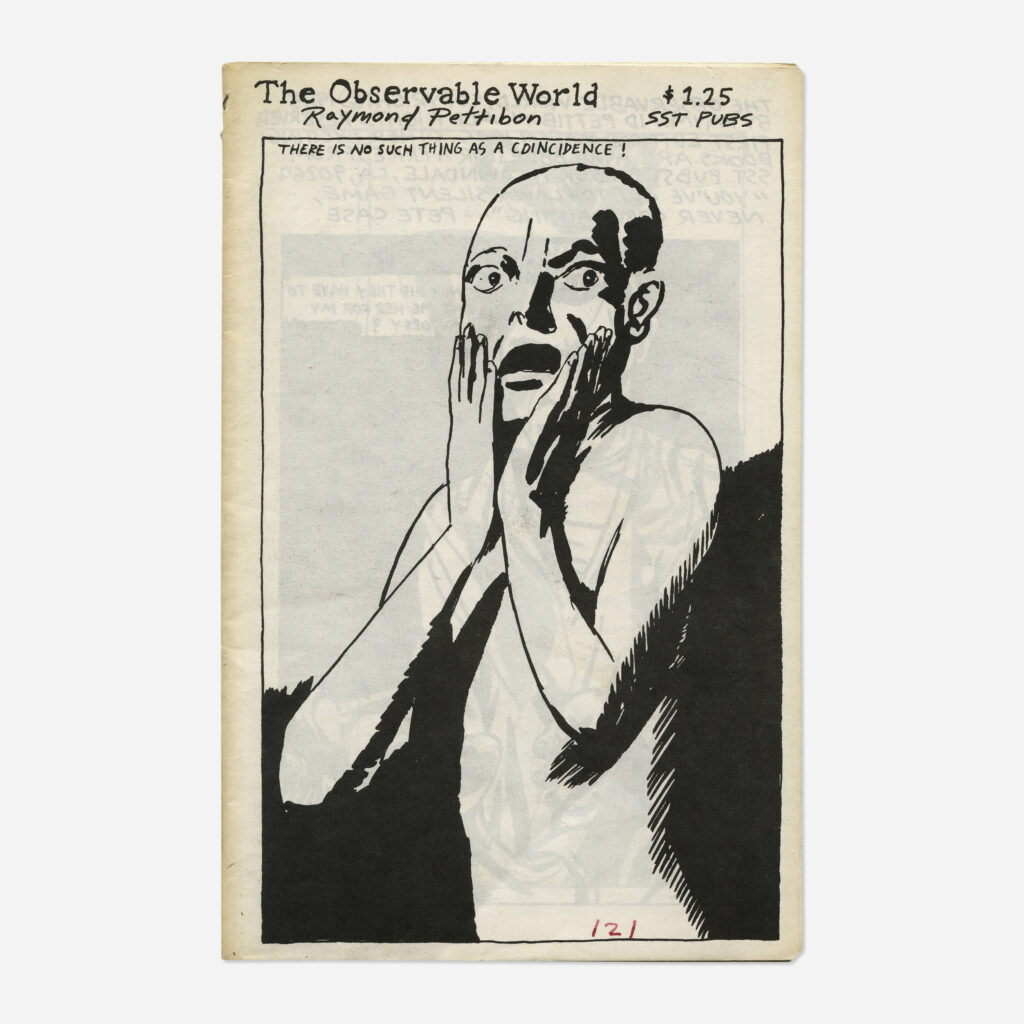

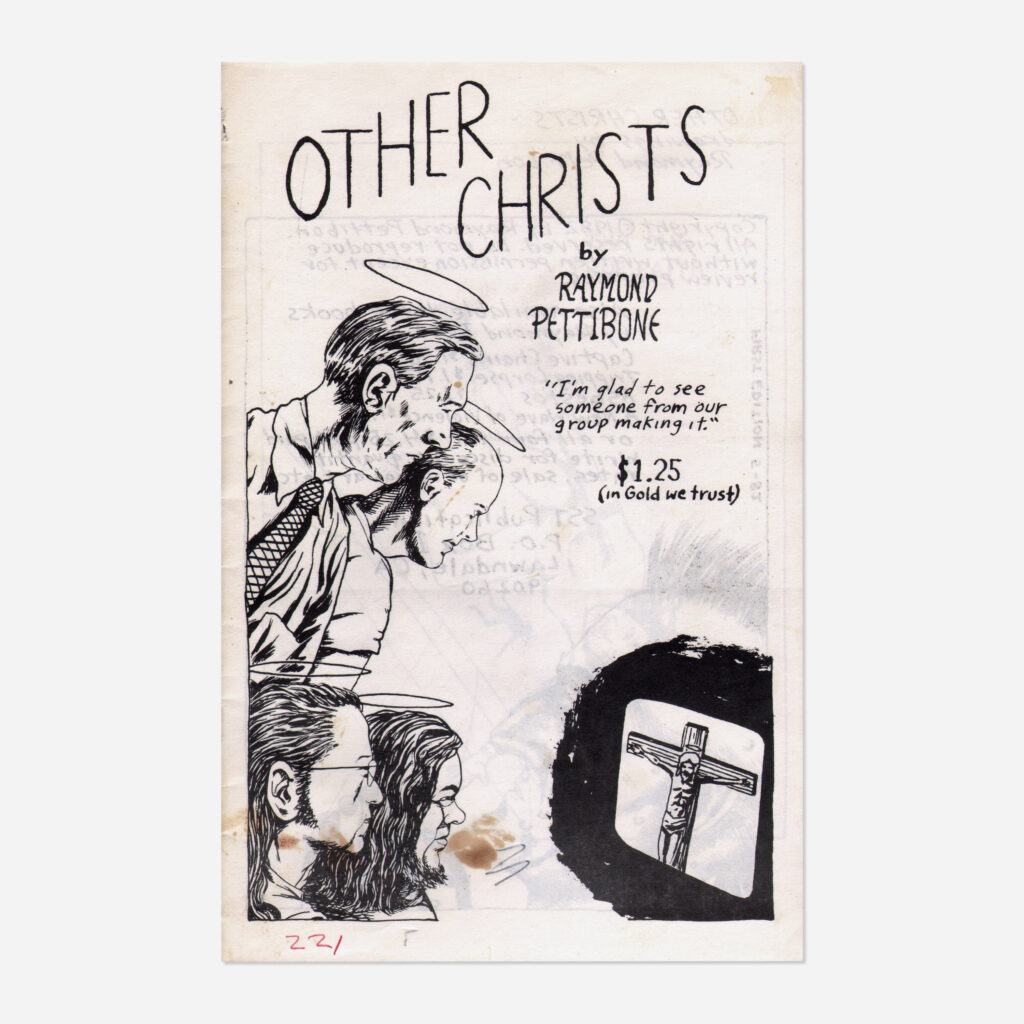

Raymond Pettibon: The Punk Years, is curated by Specific Object, a New York bookstore and gallery run by former MoMA curator David Platzker, there are somewhere around 300 items for sale, and not all of them are just flyers. Some are fanzines, shirts, tapes, records, and most interestingly, a couple of well-used, thrashed boards signed by the artist himself. All of it comes from the personal collection of Platzker, who collected most of these things while he was growing up in LA and going to high school in the late 70s and early 80s.

Raymond Pettibon, born in Arizona to Irish and Estonian immigrants, quickly moved with his family to Hermosa Beach, California, and along with his brother, Greg, he quickly found a place in the burgeoning hardcore punk rock scene of the time, although Pettibon says his position in the scene was totally by circumstance, a result of his artistic talents and the local music scene meeting at the right time. “My work was just drawings, and basically drawings just as I would do now. They weren’t done with any aspirations of becoming a part of that scene. They weren’t about punk. They were just collections of drawings, some of which I xeroxed and sold … I would sell them to anyone I could. But it was never my goal to capitalize on punk. I could never make it as a commercial artist.” he reminisced.

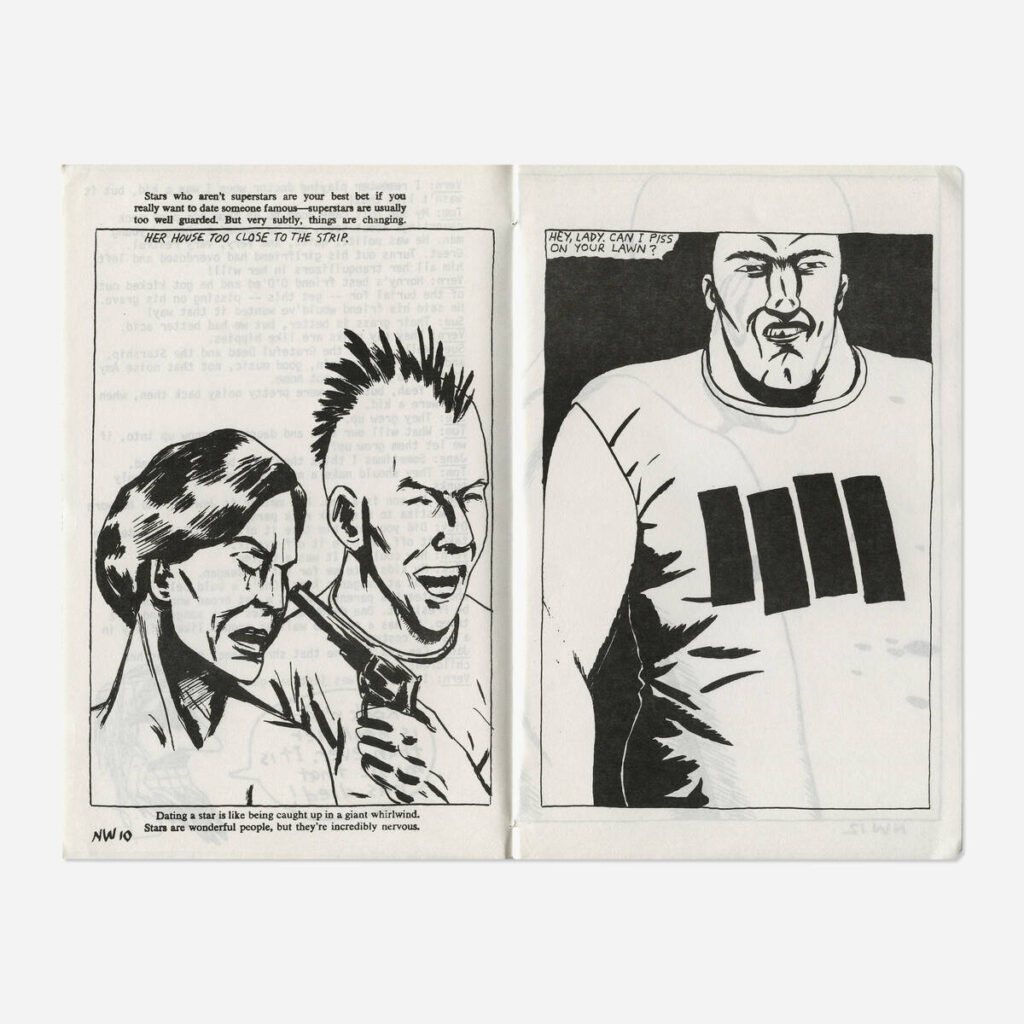

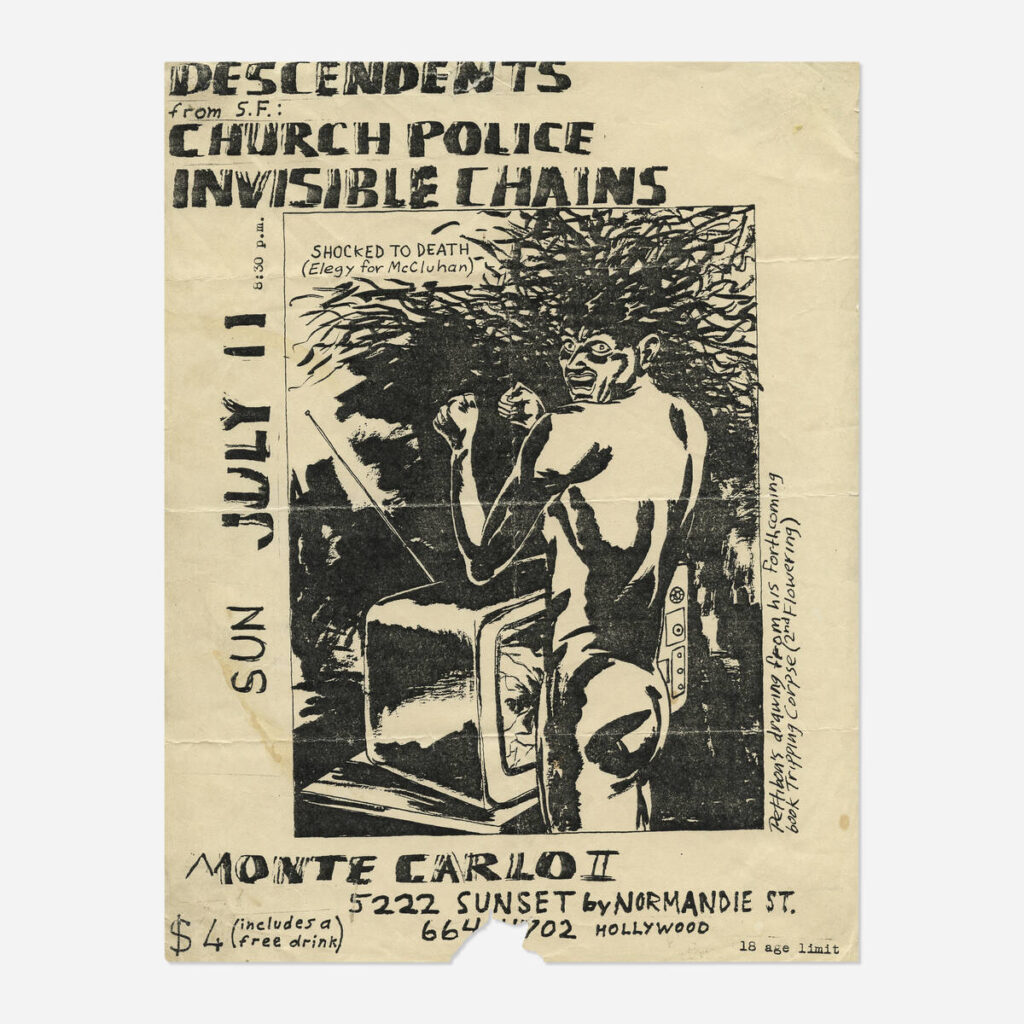

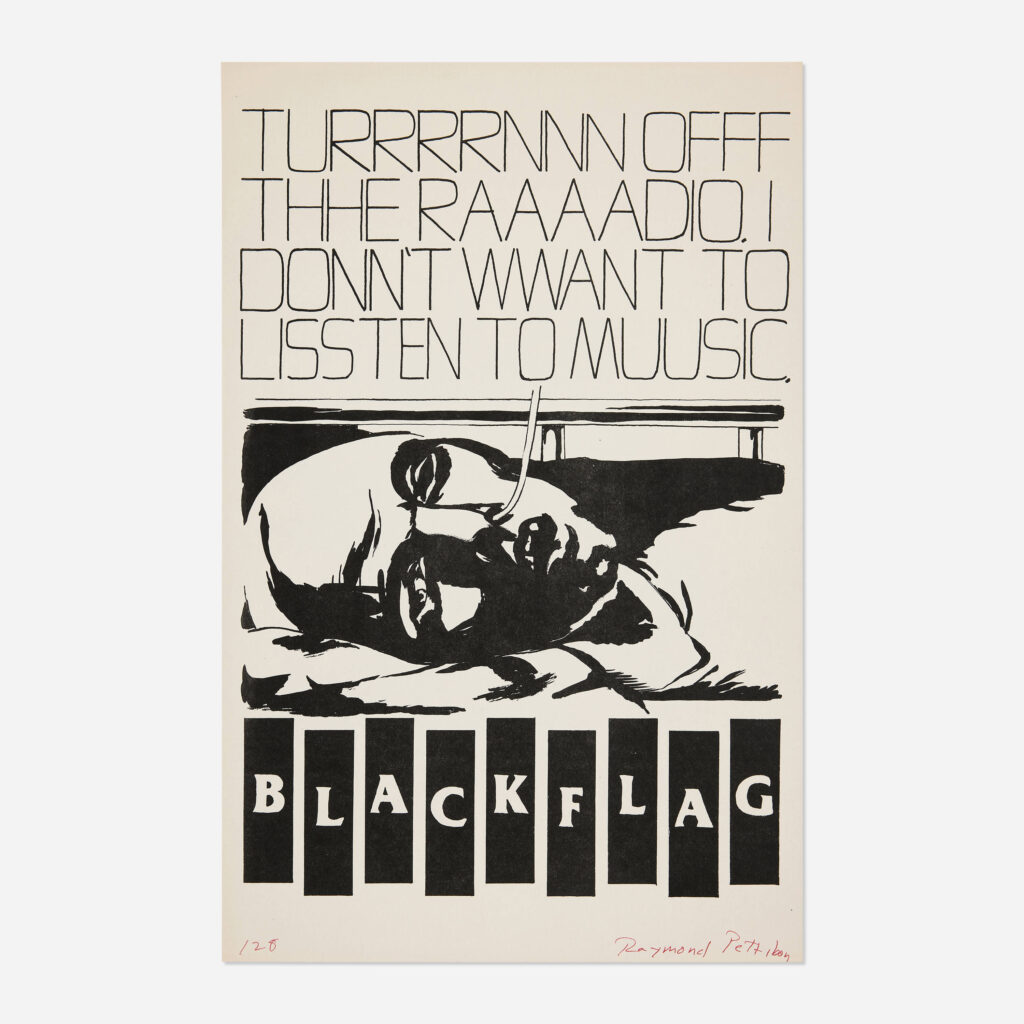

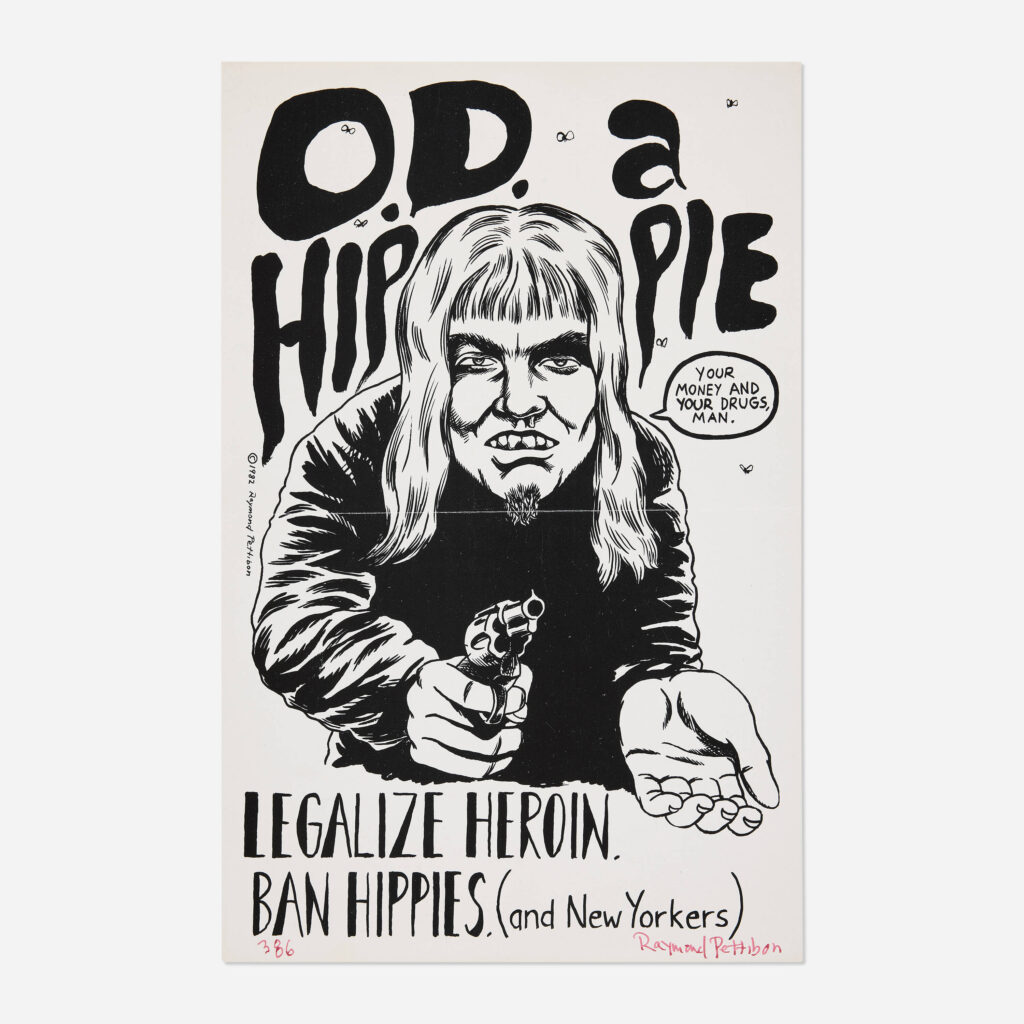

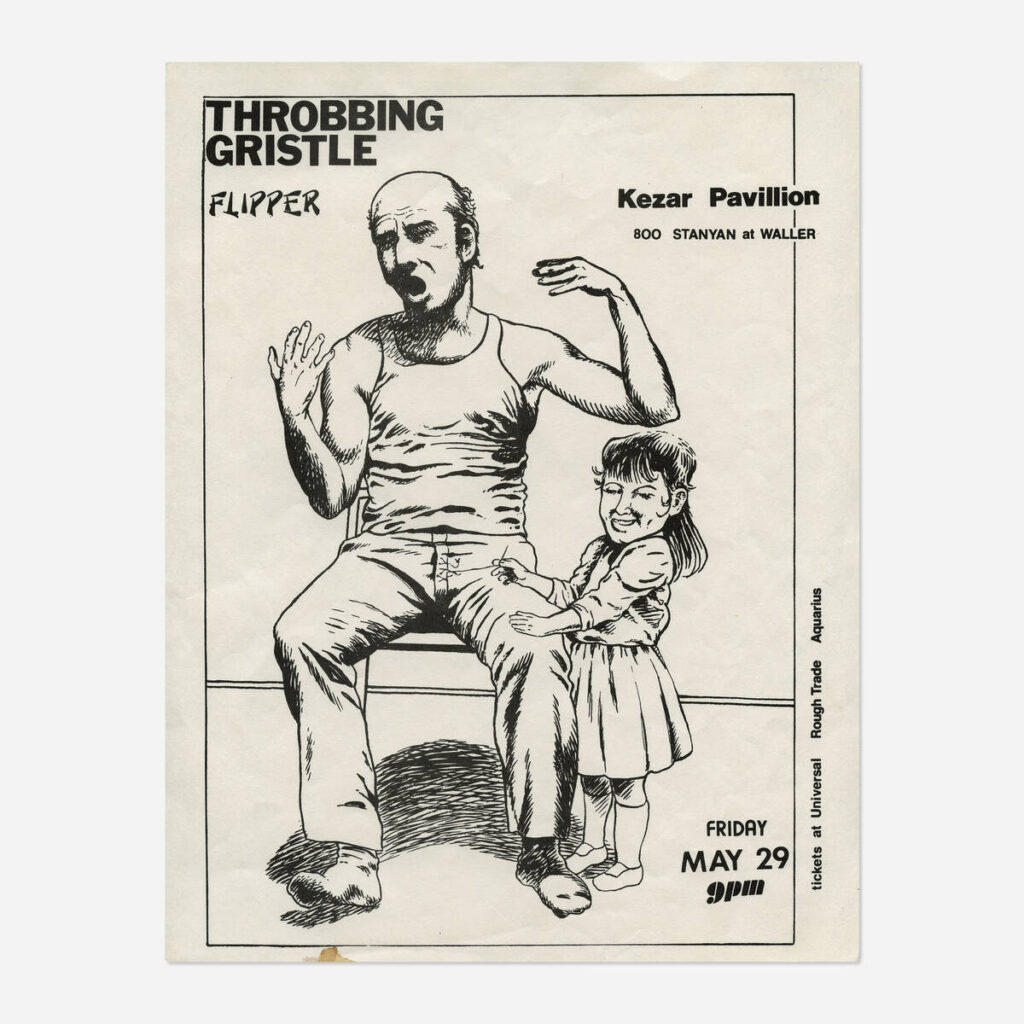

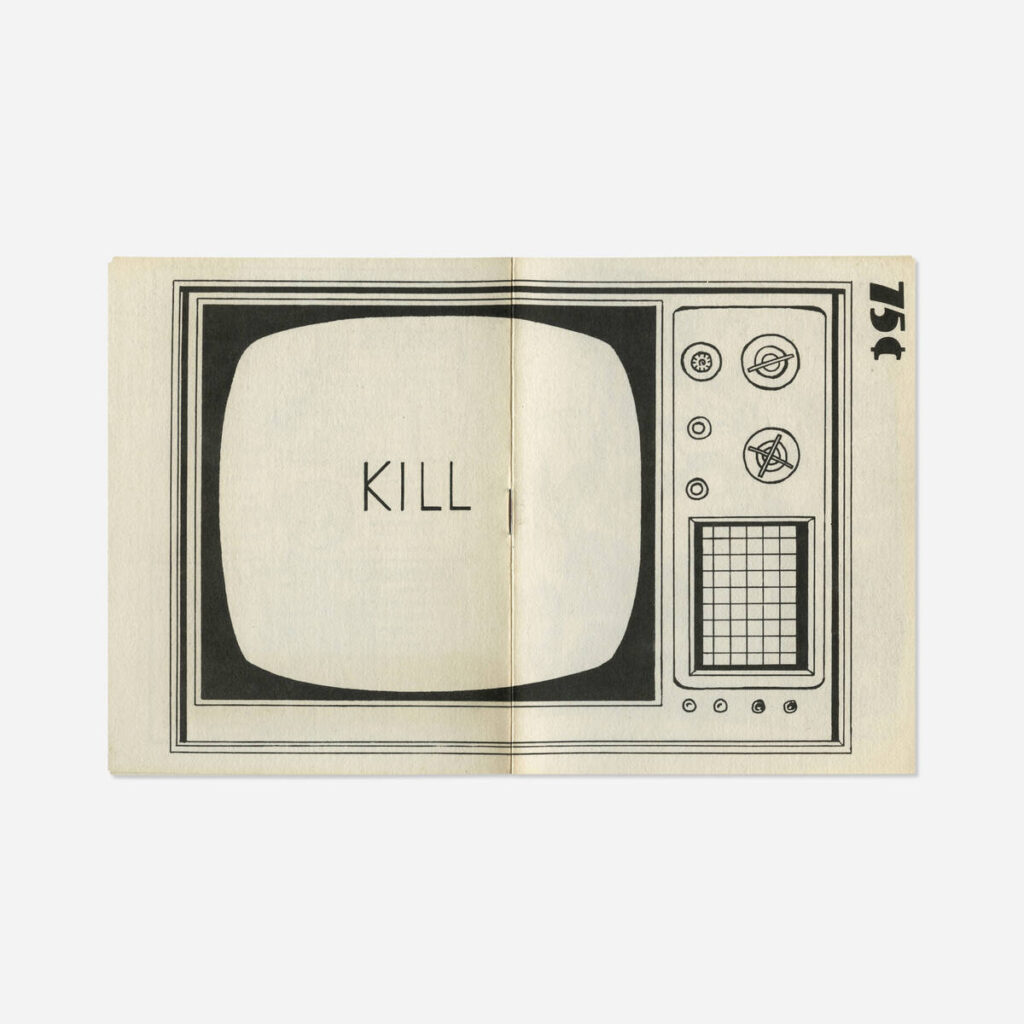

At the time these shows were happening, the aesthetic of punk rock wasn’t as nailed down as it is now, and there was no money in it (meaning no one could co-opt it and sell $500 factory-made battle jackets to rich kids) so everybody involved was trying whatever to see what would stick. Pettibon in particular was doing everything from word collages to parodies of advertising and pop culture at the time in his art, eventually zeroing in on the one-punch gratuitous graphic style in which a story is told using just one panel, similar to the wordless novels championed by someone like Frans Masereel in the 20s or Martin Vaughn-James in the 70s.

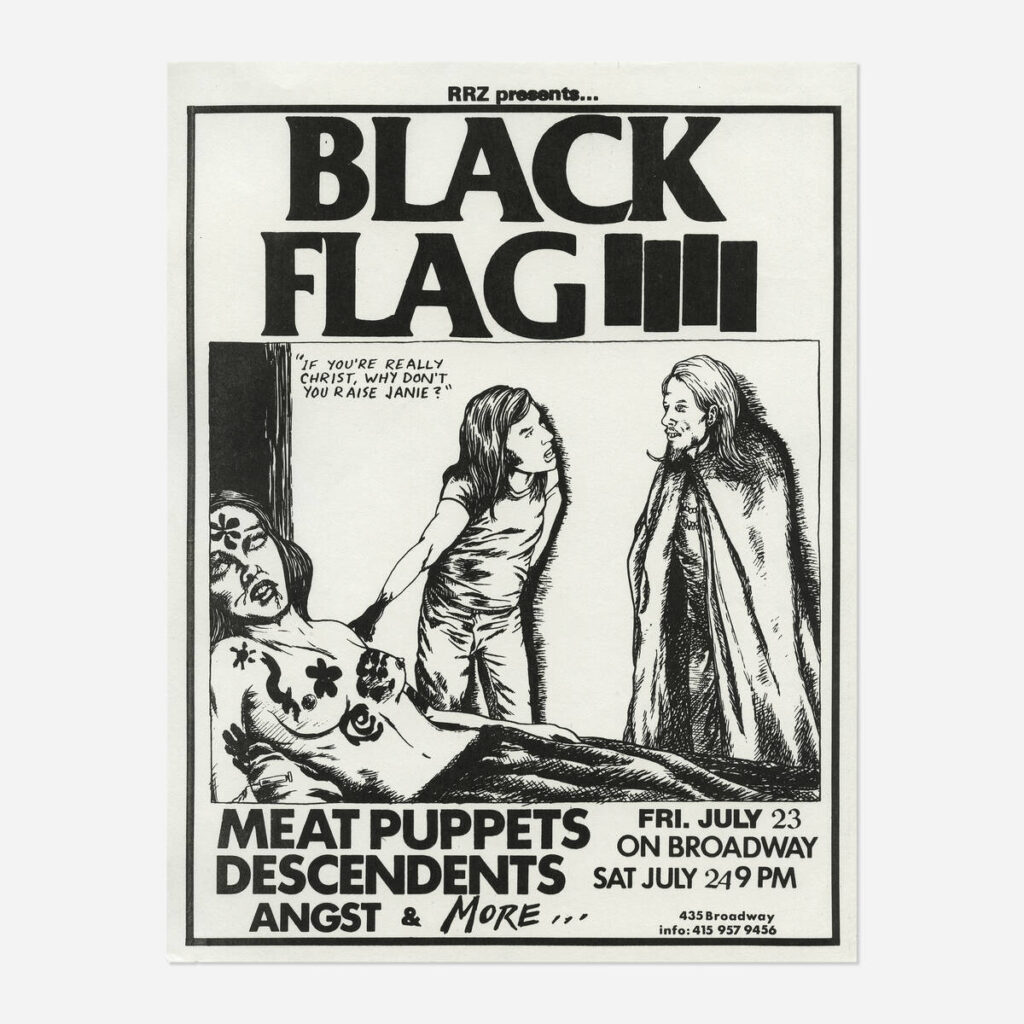

Needless to say, for a flyer, there was only room for one picture, and it had to encompass everything that the band wanted to say, so as far as any punk band is concerned, they were always going to be as provocative as possible, with no room for nuance. In the artist’s own words, “You can’t tell a whole story with all kinds of exposition. It’s like taking one frame out of a movie or one crucial scene out of a book at a critical point. You can’t really be subtle.” I would love to have seen these out in the wild and the reactions of passerby who weren’t in the know.

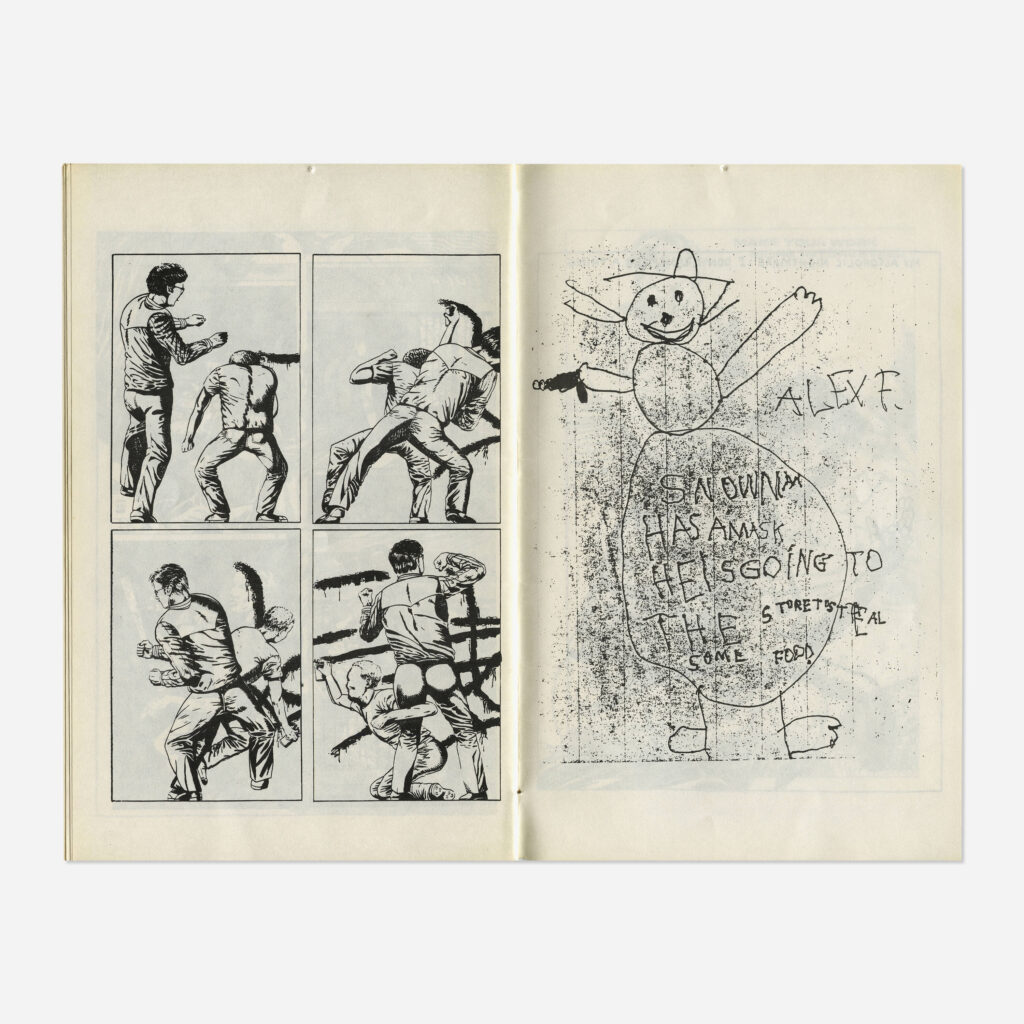

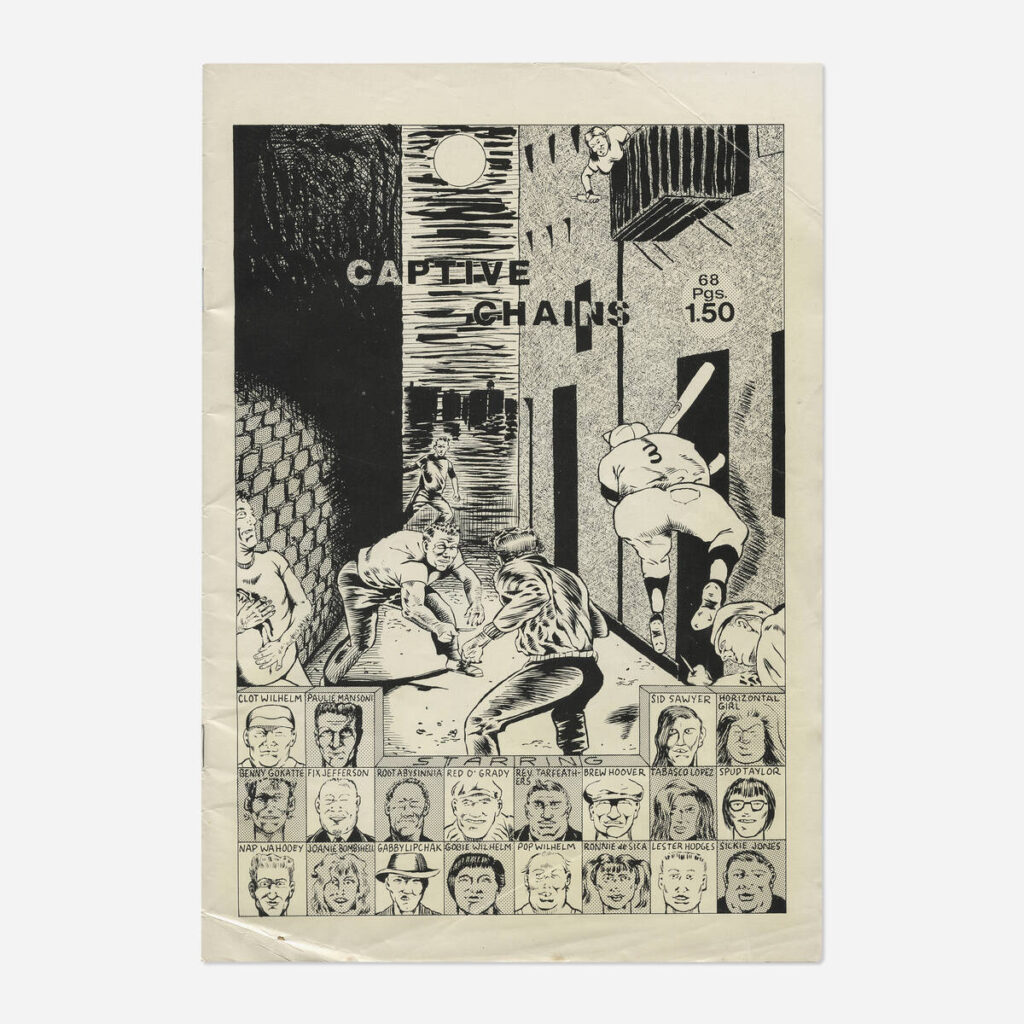

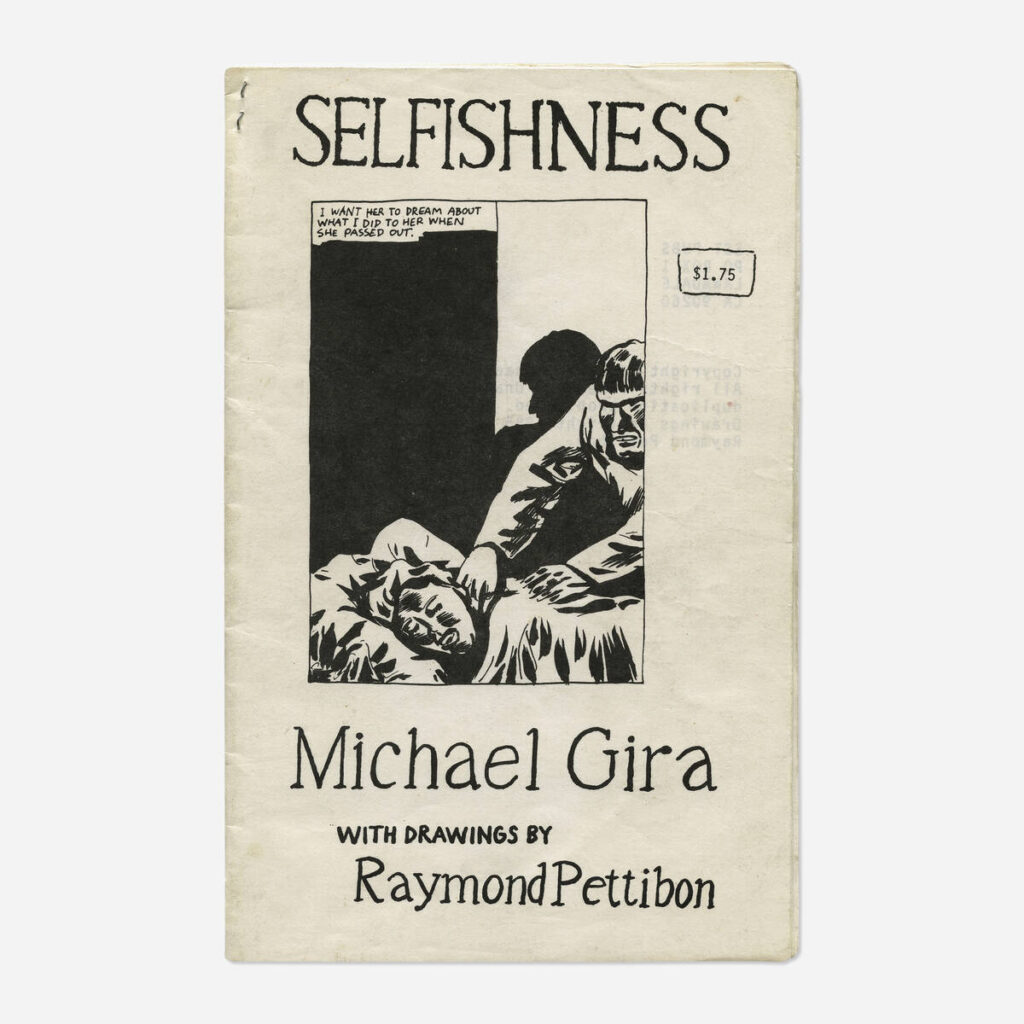

Pettibon’s art often drew from Black Flag’s lyrics, but more frequently, it was a snapshot of his own cultural landscape. A series of 47 zines created by Pettibon and published by his brother Greg Ginn’s label SST Records, provided the raw material for many of his flyers. These zines were “one of the best things about working with SST,” he said. “It’s not something that you can buy in a store or see on TV. You see it at a glance and you can’t switch it off.”

His technique—ink on paper, single panels—draws parallels with comics and the blown-up single panels of Roy Lichtenstein. Pettibon’s brutal depictions have been compared to George Grosz, Goya, and Daumier, who similarly showcased life in its rawest form during their time. Other people have compared his stuff to the old pulp magazine drawings of the 30s and 40s, and even medieval manuscript illuminations of tortured saints.

Sometimes he included drawings by his kid nephew alongside his, or he taped movies or shows on VHS, paused the tape, and adapted the frame for his drawings. But despite creating his art from what he knew, there is no introspection and none of the art is personal. He’s no Robert Crumb, nor does he want to be, as Pettibon insists throughout his career that none of the art he makes is meant to be autobiographical, merely a reflection of the milieu around him.

Black Flag’s identity, crass and sardonic, is forever intertwined with Pettibon’s art, and the inherent vulgarity behind it echoed across the ages, influencing punk and music in general to this day. Take the flyer featuring an up-close dong with “love” scrawled on it–several decades later, it served as the inspiration for the band Death Grips’ infamous album cover for No Love Deep Web, the scene recreated IRL. In response to a time frontman Henry Rollins tried asking Pettibon for a specific illustration from him, he realized one lesson: “Don’t tell Ray what to do … You’ll notice there’s a solid year of Black Flag flyers where it’s nothing but erect penises.”

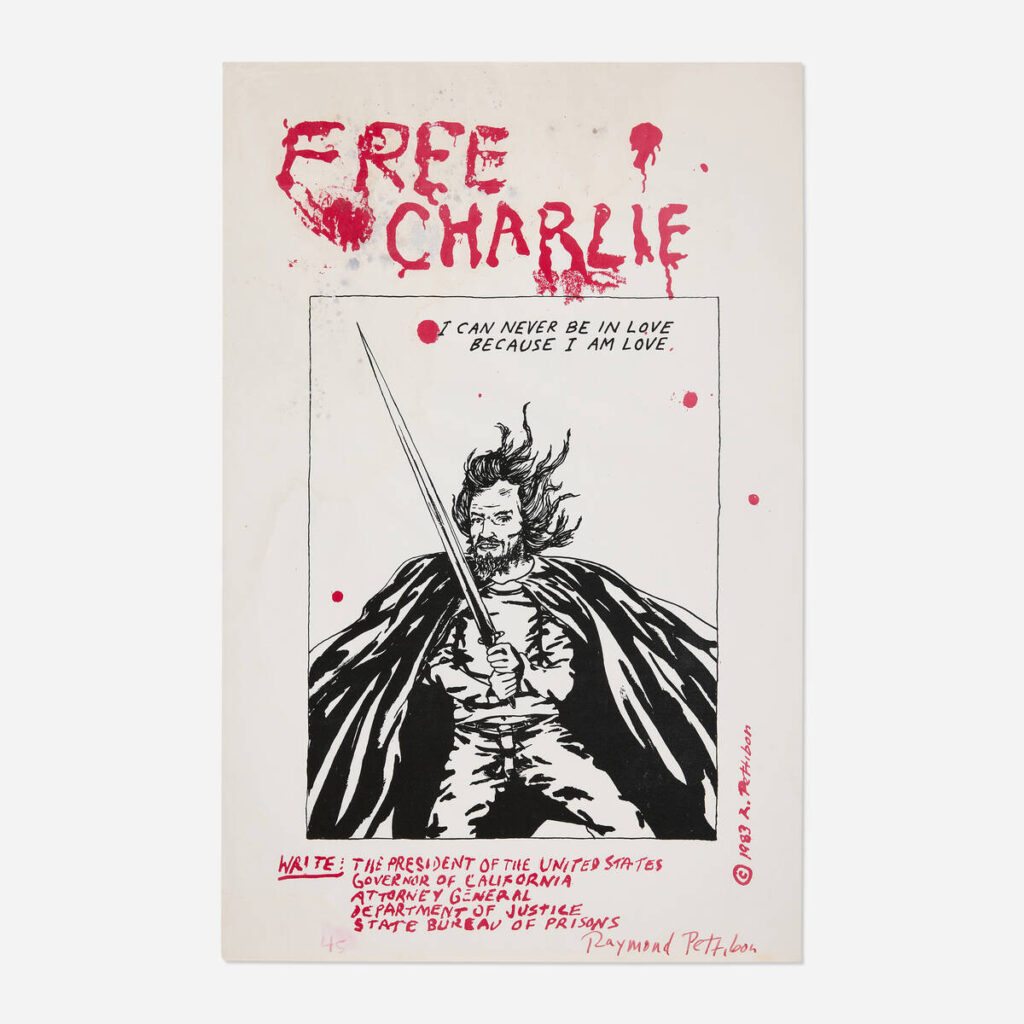

Clearly, the art is supposed to be confrontational. The flyers were like a middle finger stapled to a telephone pole, daring you to react. Sometimes the flyer is literally a drawing of a middle finger. It’s the kind of thing where you were meant to be walking around Torrance or Lawndale or wherever Black Flag was going to be and be stopped in your tracks by a crude drawing of Charles Manson being crucified or a cop with a gun in his mouth. Even Flea from Red Hot Chili Peppers recalls, “Before I knew what Black Flag was I remember walking around Hollywood and seeing Raymond’s flyers and being like, ‘What the fuck is that?’… Those flyers made me feel like something is going on and it’s romantic and it’s mysterious and it’s heavy and I don’t know what it is but I wanna know.”

Whatever reaction people might have to the art, it was very much of the time. An amalgam of the angst-ridden youth zeitgeist in 70s and 80s SoCal. Pettibon’s art, and the punk period in general started out playing on the familiar suburban fears and panic borne of sensationalized news reports and classic movie archetypes, combined with the restless need for mindless, ignorant self-expression. It’s as much about drug-crazed killer hippies as it is about low-life businessmen and hysterical femme fatales from film noir.

Pettibon didn’t stop at Black Flag either, his art made it on the flyers and albums of bands like Circle Jerks, Minutemen, Throbbing Gristle, Descendents, TSOL, and Hüsker Dü. And just two years before his falling out with Black Flag, he held his first gallery show at 27.

Four years after leaving the band behind, he got the opportunity to design the album art for Sonic Youth’s ‘Goo’, formally breaking out of the local punk scene, which was more confined to the West Coast back then than it is now, and turning him into a more widely recognized artist.

Pettibon always sought to eschew his cult status as a “punk artist”, he is a more traditional artist now, and he’s everywhere if you know how to look, doing everything from surfing paintings to large-scale baseball murals in Brooklyn, and for a while now he’s had the attention of big gallery owners and museum curators. He’s even collaborated with huge artists like Ed Ruscha. Personally, I’ve even seen his art hanging up in upscale suburban restaurant bathrooms, which surely nobody from the Black Flag days could have seen coming.

Although his ink-on-paper technique has largely remained unchanged since his years in the punk scene, Pettibon has gone much deeper with his subject matter, incorporating literary references from writers such as Samuel Beckett, Marcel Proust, Charles Baudelaire, Jorge Luis Borges, among others, no doubt an interest instilled or at least influenced by his father, who was an English teacher. He even published a reader of the works he was most influenced by so you can maybe catch up to his level.

Yet the violence and crude pop culture elements remain even now, and the continued interest in Pettibon’s art is probably in no small part due to his ability to go high and low, balancing an enduring appeal that applies to the art world as well as the streetwise.

As a personality, he’s no less capable of range, and there are numerous interviews where you can get very deep insights into what he thinks about his art and the world at large, such as a great conversation with Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth in Interview Magazine. But he’s also got a very blunt, unembellished side to him, best exemplified in my personal favorite, an interview he did in Berlin for Sleek, in which he got absolutely wastoid blitzed in the afternoon, had to be driven there (was an hour late anyway), and mostly only managed to shit-talk all of the most recent presidents of the US while praising the assassins of the Kennedys as his heroes. The interview only lasted four questions before the journalist presumably tapped out. I love range.

His art is still going strong in the music scene, gracing the albums of new-ish bands like OFF! And Cerebral Ballzy. Pettibon is a musician himself, briefly playing bass in rehearsals for Black Flag with his brother (before leaving to focus on school) and performing in a number of personal projects and collaborations in the years since, bands like Super Session, Sock-Tight, Psing Psong Psung, and Sür Drone.

These days, if he’s not busy making more art, you can find him on his Twitter/X, where he mostly posts standard Gen‑X political banter, only taking short moments to stop and write from the heart about his passion for dog fighting and the pit bulls he breeds for it. Although he also claims he raises them for a charity that gives them to impoverished kids who can’t afford dogs. It’s a running joke of his, but still, no one can seem to tell if he’s serious on either count or if there are even any dogs to begin with. You seldom know if he’s ever sincere and certainly, that’s part of the charm with the art in this auction.

All this art will scatter across the world in a few days’ time once the hammer drops, but it’s a good opportunity to see what these items look like and get a brief peek into an old music scene. And if you still want to see more, some of Pettibon’s zines are up in places like the Internet Archive if you’re curious to read them.

Like the throwaway superhero comics of old, Pettibon’s work was created for the time and place. Now a testament to a bygone era, they’ve survived long enough to have become cherished artifacts—or maybe just pricey reminders of a time when punk was considered something raw and real.

Either way, Pettibon never took any of it seriously and seemed to know what was up in the moment, in a 1984 interview with the LA Times he predicted auctions like these were going to happen, saying “It’ll happen like it did in the ‘60s with the psychedelic posters … Once these kids start growing up and making money, it’ll be a way of recapturing their past. But at that point the art becomes dead. It’s just artifacts.”

Raymond Pettibon: The Punk Years, curated by Specific Object and David Pratzker, hosted by Wright Auction House and Los Angeles Modern Auctions, is open to online bidding until August 22, 2024.