Raph Rashid’s intimate photographs map the domestic environments where hip-hop producers build influential records, showing how constraint, routine, and personal space become part of the music itself.

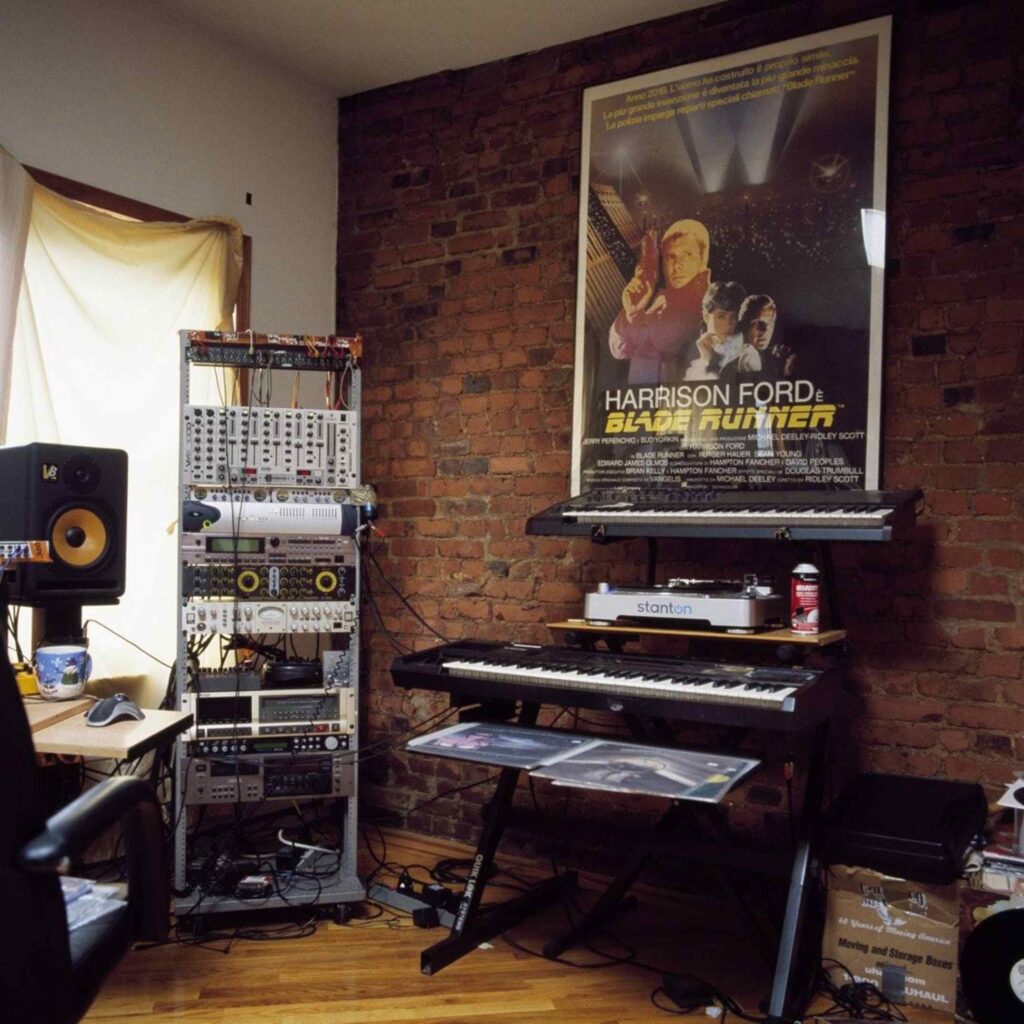

For more than three decades, independent hip-hop producers and DJs have created influential, often genre-defining music far from the world of high-end recording studios. Bedrooms, kitchens, basements, garages, and even bathrooms have served as laboratories of sound, where limitations of space and budget are offset by ingenuity and persistence.

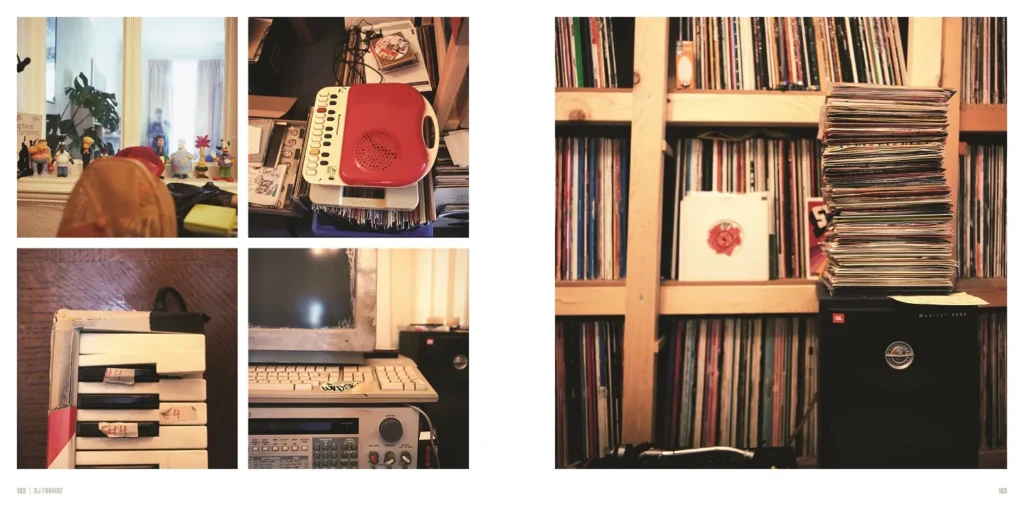

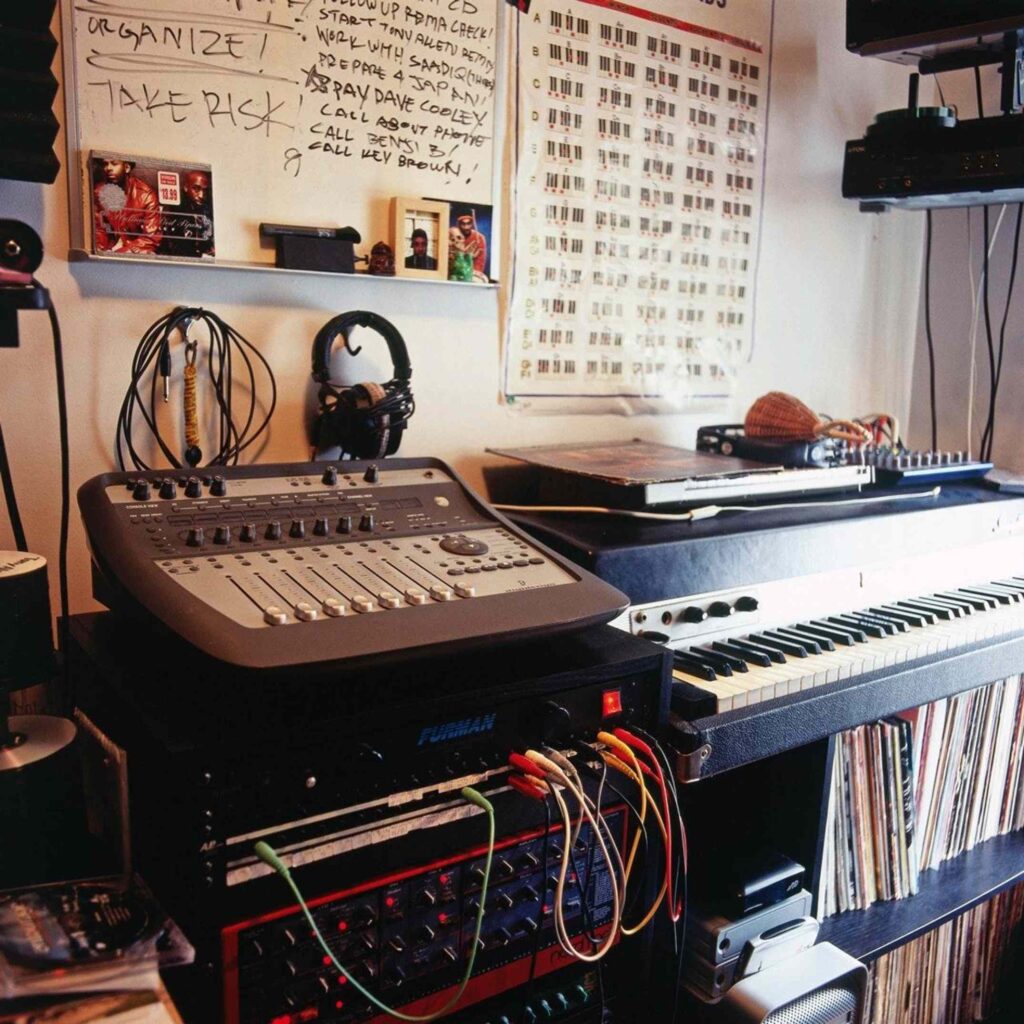

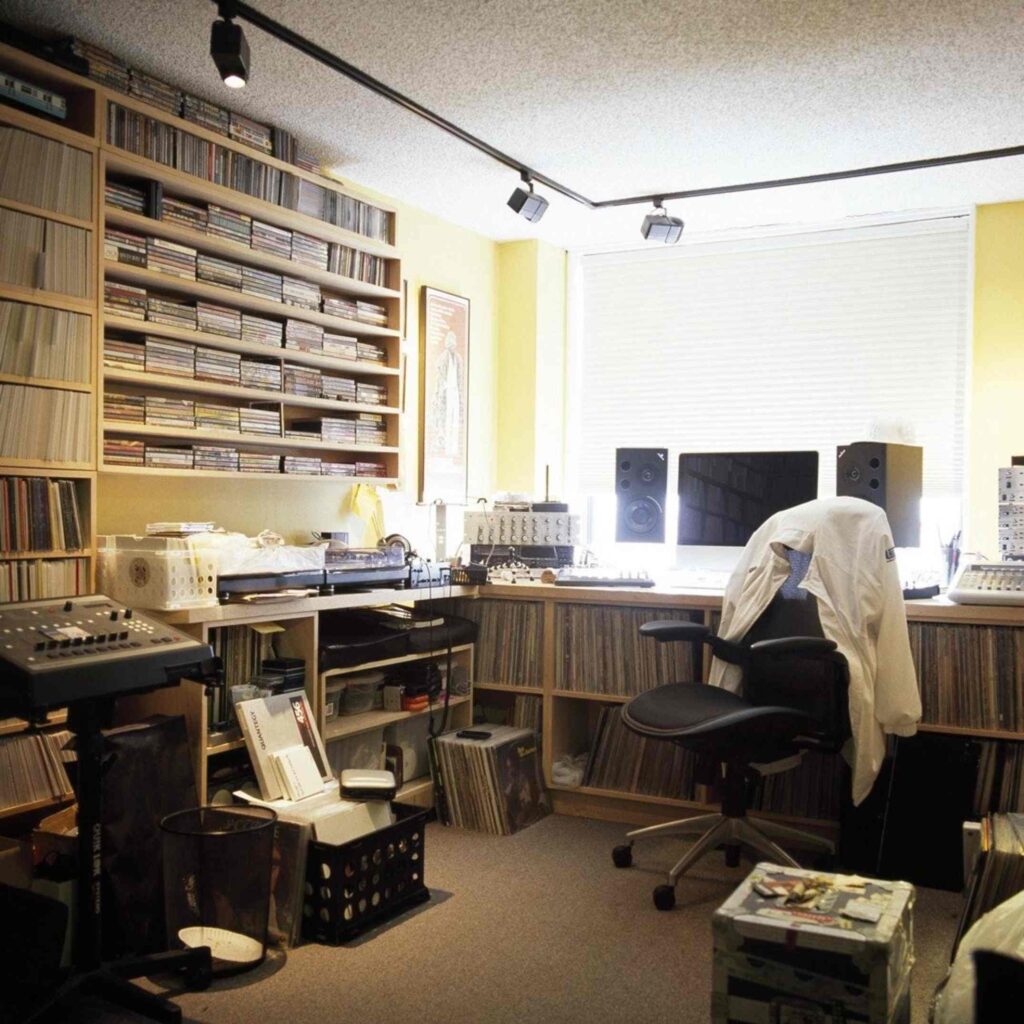

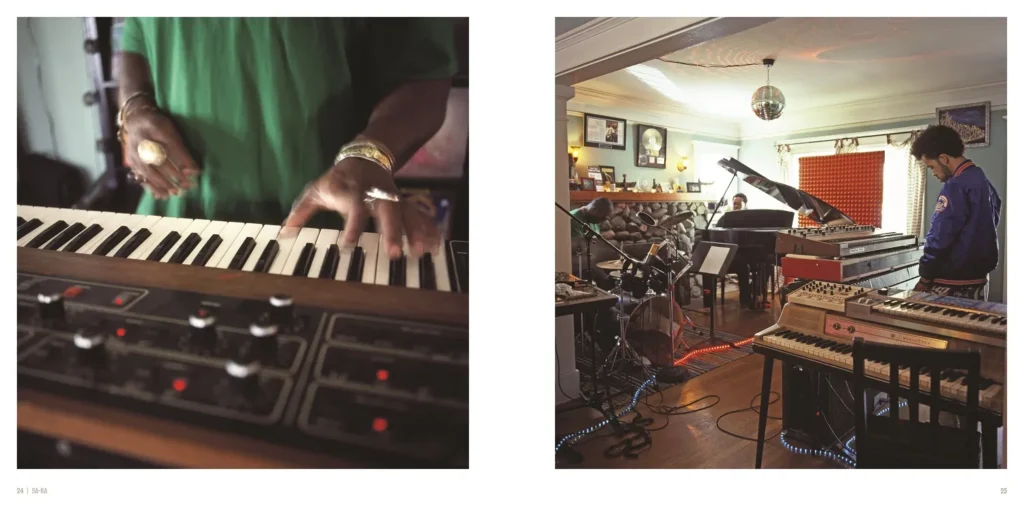

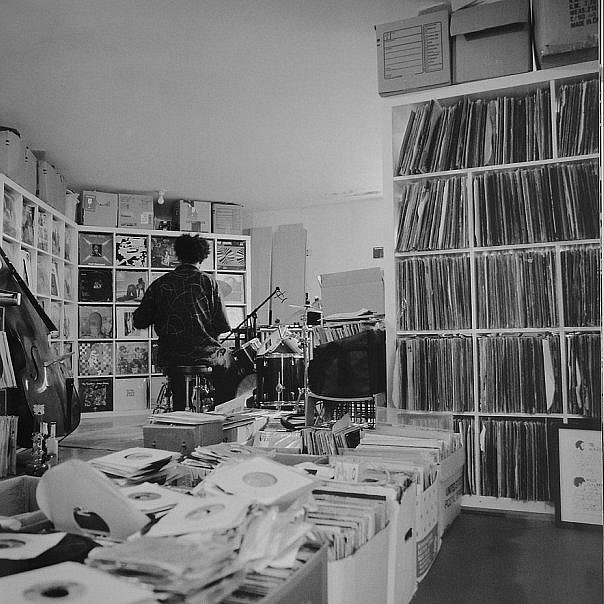

Australian photographer Rafael “Raph” Rashid has spent years traveling internationally to document these private environments, gaining rare access to the domestic workspaces where beats are conceived and refined. His photographs and accompanying notes reveal the remarkable diversity of in-home studio setups, pairing portraits of producers among their instruments, gear, record collections, and personal ephemera with contextual details about their surroundings and essential releases.

Rashid has emphasized how unfamiliar these spaces can appear to outsiders: “To walk into a house and immediately be faced with a studio space rather than a living room is unfathomable to the average person. But when an individual is deep in their craft, the passion takes over … Hip-hop producers always find a way, and when faced with limitations they let their creativity shine through.” This ethos underpins his long-running project, which situates creative practice within the lived environments that sustain it.

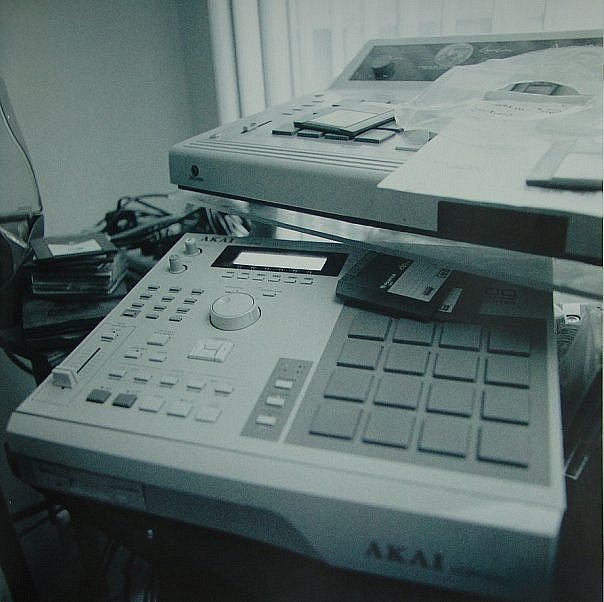

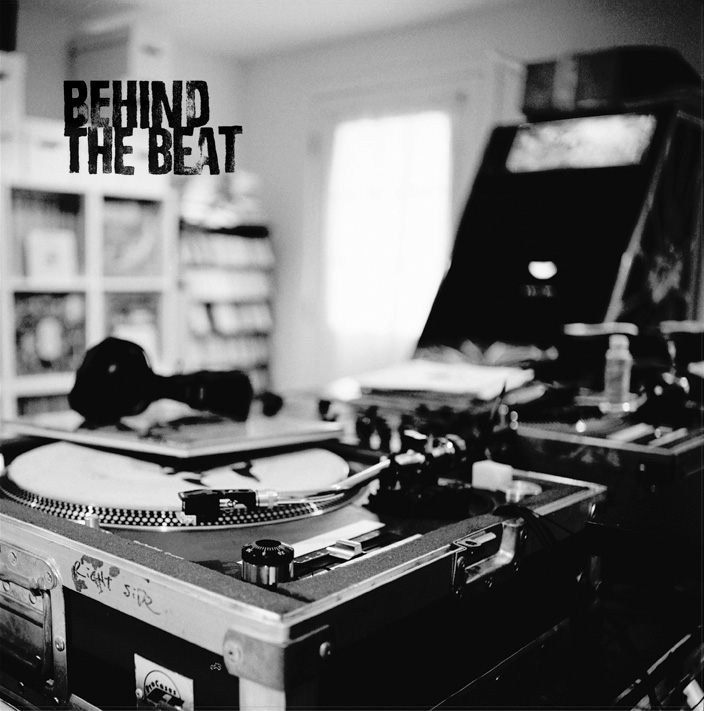

His first major volume, Behind the Beat (2005), is a collection of 320 photos published by Gingko Press, emerged from years of photographing producers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and his native Australia. Shot largely on a square-format Hasselblad, the book contains hundreds of black-and-white and color images that place figures often known only from liner notes into a visual context.

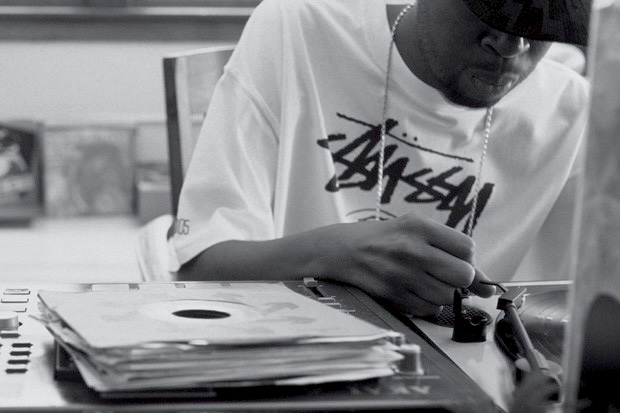

The photographs document studios and equipment belonging to artists of the time such as J Dilla, Madlib, DJ Premier, DJ Spinna, E‑Swift, KutMasta Kurt, Da Beatminerz, DJ Shadow, Dan the Automator, Chief Xcel, Cut Chemist, Thes One, J‑Zone, and many others. The accompanying material is deliberately concise, allowing the photographs to convey the visual identity of the music. As one description notes, “More often than not, producers are just a name on a record, always in the background. These pictures capture the visual side of the beats they make. They are the images behind the beat.”

The project grew organically. Rashid began photographing his local skateboarding scene but soon turned the lens to a more domestic subject. Fascinated by how his musician friends organized their living spaces around creative work, he began to photograph them, beginning around 1995.

One early memory involved a friend producing techno whose equipment was chaotically spread throughout the house. “My friend lived with his father and he put all his studio equipment all over the house, mainly in his kitchen.” he explains, “I remember going into his kitchen, into his house. It was just a regular apartment, but it was set up in a way that was just all about his craft. I remember being blown away by that at the time, thinking I need to take a photo of this.” The experience left a lasting impression and suggested the photographic potential of documenting such environments. A few years later around 1999, the scope expanded to photographing artists from around the world.

Rashid explains that getting access to producers all came down to connections, “I would make a short list of friends that I had and friends of theirs and then I would see if I could get a connection.” A shoot with DJ Shadow, secured after meeting him on tour, led to further introductions, enabling access through personal networks rather than formal channels. “Producers know producers, and that would keep rolling.” he said. Sometimes, a single shoot led to another, unplanned shoot later that same day, as was the case with Kenny Dope, who, accompanied by DJ Spinner, drove Rashid to Jazzy Jeff’s house, who lived four hours away.

Behind the Beat achieved wide recognition, selling out at least six printings and eventually contributing a print of an iconic monochrome photograph of J Dilla working on The Shining to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Following the success, Rashid continued photographing studios, expanding the archive and refining his approach.

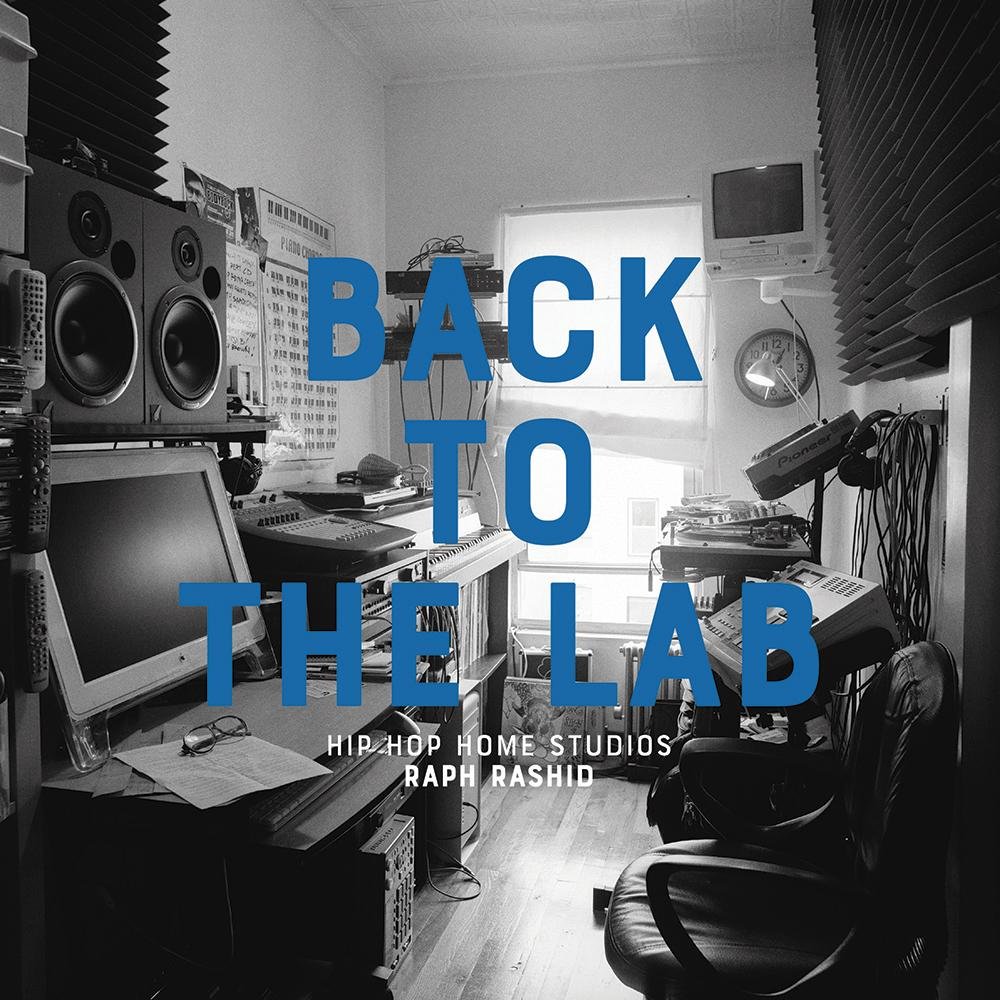

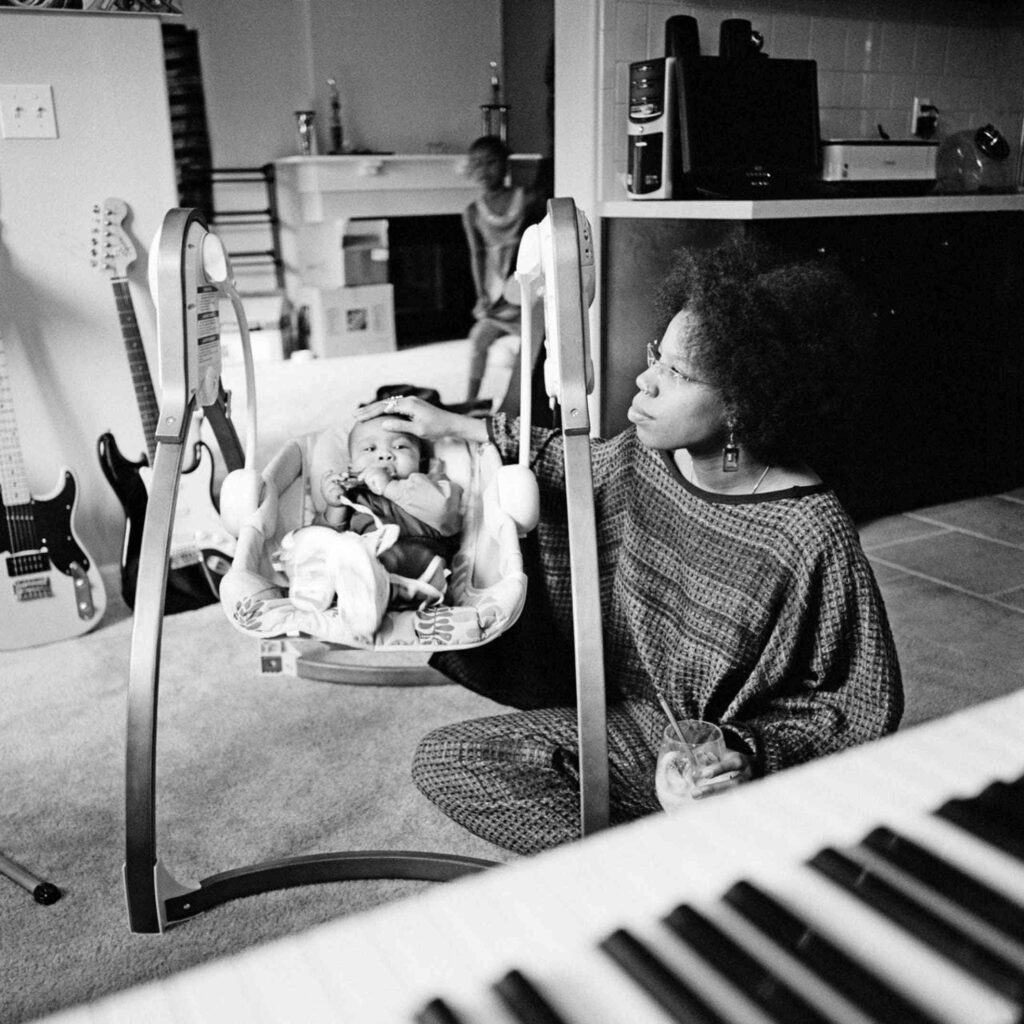

The 2017 sequel, Back to the Lab: Hip Hop Home Studios, extends the scope of the first book, documenting both established figures and emerging talent. Featured producers include The Alchemist, Ant, DJ Babu, El‑P, Georgia Anne Muldrow, DJ Jazzy Jeff, Kenny Dope, Lord Finesse, Oh No, Dabrye, and Flying Lotus, among many others. The book continues Rashid’s effort to document veteran producers he previously missed while remaining attentive to newer voices shaping the sound of contemporary hip-hop.

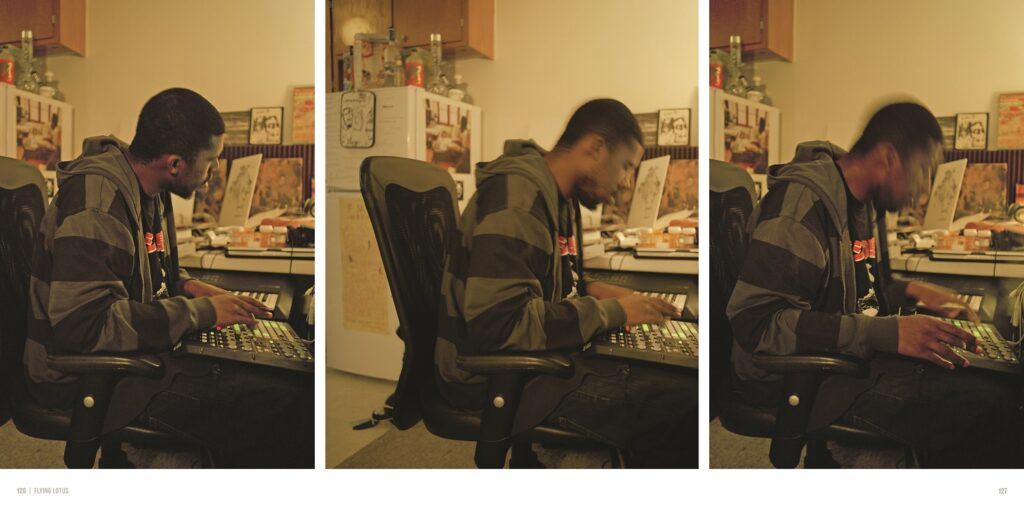

Rashid’s photographs reveal how domestic environments and creative work frequently merge and spatial constraints vary dramatically. In Flying Lotus’s one-bedroom apartment, the refrigerator sits directly behind the studio setup. Kenny Dope had one studio in his home and kept the rest of his equipment in a second studio art his mother’s home. Georgia Anne Muldrow’s mixing board rests on her dining table, where she also prepares vegan meals with her husband Dudley Perkins. Oddisee worked in a room barely two meters by two meters, strikingly tight given his height.

Rashid links these improvisations to hip-hop’s early history, referencing footage of Grandmaster Flash in Wild One working in his mother’s kitchen and noting that the practice of making music wherever space permits remains largely unchanged. “In a studio, which is pretty utilitarian, if you’re a producer you just kind of get your stuff and plunk it down and then start working … but even those spaces, producers seem to make them beautiful in their own way.”

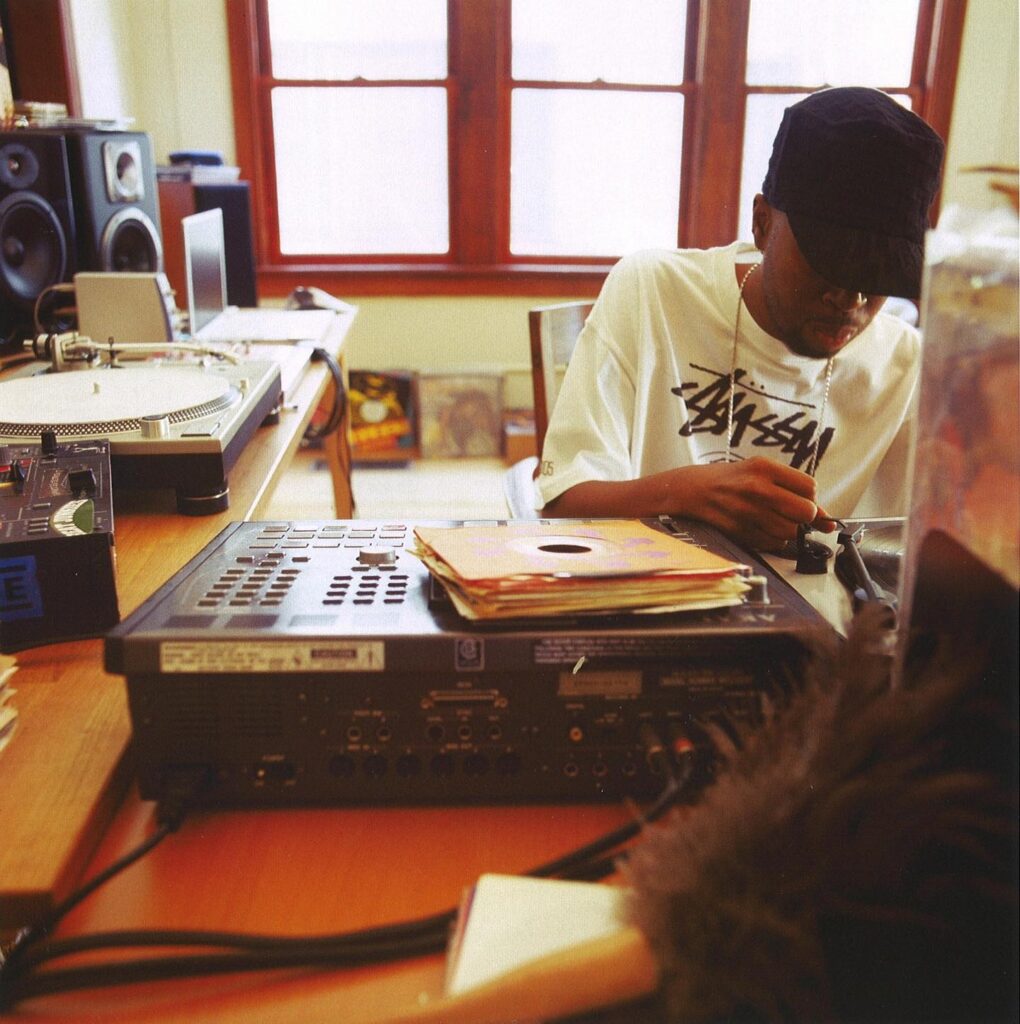

Rashid occasionally witnessed artists working during shoots. Observing J Dilla at work just a year before his untimely passing left a profound impression: “That was incredible and really humbling. I had read some interviews before that said he’d asked people to leave the room to give him space to program ’cause he liked to do things by himself. But I was there and he was super nice and was like, “I’m just gonna keep working if that’s cool?” Watching him sample and make the beat and do all that stuff was really surreal at the time. He was really, really fast and he just knew exactly what he wanted to do and it was just coming out amazing.”

Similarly, Flying Lotus continued producing while Rashid photographed, telling him to do whatever he needed to do while he worked, treating the session as routine rather than performance. Other performers, such as Alchemist, were so engrossed in their work that they needed others to show Rashid around the studio. “When someone’s actually making music while I’m there, I feel very, very privileged.” he reflects.

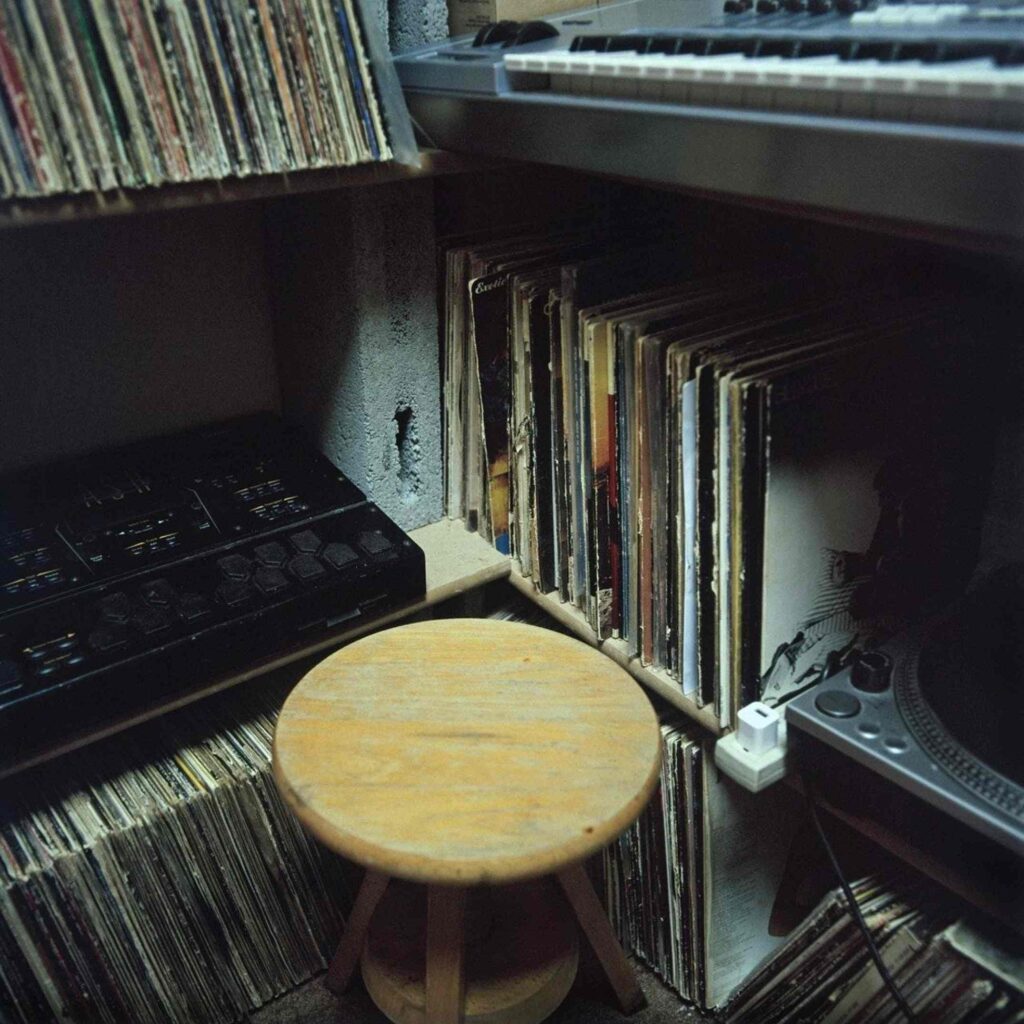

The contents of the rooms themselves often disclose as much about the producers’ lives as their rooms would. Arcade cabinets stand beside racks of gear; microphones mounted in bathrooms for vocal takes; shelves hold sneaker collections and dense vinyl archives; toy figurines, comic book art, and gaming memorabilia form small personal shrines.

Other, more unusual, details underscore the lived reality of these spaces. El‑P’s studio floor included scattered sneakers and socks; In Muldrow’s kitchen studio, a child’s crib sits within arm’s reach of the workstation; Flying Lotus’s workspace contained medicinal marijuana containers; The Alchemist kept a prominent jar of the same stuff nearby. Rashid likes it that way, deliberately avoiding staging or rearranging anything, preferring authenticity over polish. He often tells artists not to tidy up and not to dress up, preserving the natural overlap between home life and creative labor.

Unconventional equipment can also shape an artist’s sound. Dabrye, for instance, relied on an aging Sterling computer system, an unfamiliar machine whose limitations nonetheless suited his sonic approach. One producer, Waajeed, even stored his tracks on floppy disks, a reminder that workflow is often dictated by whatever tools are preferential rather than by technological fashion. Throughout these visits, the photographer maintained a deliberately unobtrusive presence. “I’m not trying to be in their way and not trying to style them, and just trying to capture them from the style they give.”

Across both volumes, a consistent theme emerges: equipment matters less than ideas. Many producers had an appreciation for analog, maintaining turntables and vinyl collections even when using digital systems, valuing tactile relationships with sound sources. Others rely on older programs or specific samplers because they align with their creative logic. Rashid found little romanticism about gear itself; most artists simply used what worked in the most convenient part of their home. As he notes, the common thread was pragmatic: “Most people were just set up in the most convenient location in their house. Whatever their spare room was, or even right there in the kitchen. I feel like the common thread was always, “This is where I was gonna put it. This is the space we had available so this is where it’s going.” Just unplanned. Spontaneous.”

Today, Rashid remains in his home of Melbourne, Australia, directing his focus to a new passion: food, discovered during his travels across the US and experiencing the local flavors, such as a late dinner of home-cooked fried chicken and waffles, prepared by Jazzy Jeff before his photoshoot using a persona deep fryer in his kitchen. Returning to Australia, he opened Beatbox Kitchen, the country’s first hamburger food truck and has since been described by the Herald Sun as “the founding father of Melbourne’s food truck scene.” Although his photography is currently on a hiatus due to business and family commitments, he remains hopeful about returning to the project, with the long-held goal of photographing Dr. Dre’s studio. “I think I definitely will continue to shoot studios,” he says. “Something will click, something will happen, and I’ll pour all my energy into it.”

In the meantime, Rashid remains in contact with many of the producers he met over the years, notably DJ Shadow, who usually stops by for a burger whenever he’s in the country. Rashid notes, however, that even famous musicians don’t get cutting privileges; they still have to wait in line with everyone else.

By documenting these environments, Rashid demonstrates how creative limitations often foster distinctive sound. The intimacy of a bedroom, the functionality of a workplace, and the freedom of artistic experimentation converge within spaces defined by personal routine and constraint.

Producers, often less visible than rappers or performers, are presented not as anonymous technicians but as individuals embedded in domestic landscapes that influence their work. Their studios are not isolated professional environments but extensions of daily life, shaped by routine, constraint, and familiarity. In these improvised settings, the boundaries between work and home dissolve, reinforcing the self-directed ethos that has long defined independent hip-hop as well as serving as a space where the producer has full control over the product and the time it takes to create it. As Rashid explains, “The home is where [musicians] feel real comfortable so the creativity is going to flow more than if they were to book a studio.”

Rashid’s biggest aim is that the work will also inspire other people to make music. “My greatest goal for the book is that it inspires someone to grab something and make something. Grab whatever it is … a Nintendo, and make a beat on it. That’s the biggest aim. One of the initial impetuses was Shadow’s Endtroducing was made at home and sold half a million copies or whatever it was. It was made in his basement. … We get so caught up with new equipment and new technology, and it’s generally really, really good, but it’s more about the ideas. [These producers] found some synths, they found this sampler—better samplers have come out, but this is the one that worked for their brain or their pattern.”

Ultimately, Rashid’s project functions as both cultural documentation and creative inspiration. The history of hip-hop production, as his photographs show, is inseparable from the homes in which it developed, environments where practicality, personality, and obsession combine to music that can resonate far beyond their walls.