Peter J. Walsh was an eyewitness to one of the most transformative moments in modern British youth culture: the birth of acid house and the UK rave scene as a whole. With his long-term photo project RAVE ONE, Walsh offers a visceral, on-the-ground chronicle of the late 1980s and early 1990s acid house and rave movement, particularly in Manchester, a city that pulsed at the heart of it all.

Unlike mainstream press photographers who captured club culture from a comfortable distance, Walsh embedded himself in the crowd, sweating, dancing, and documenting as an insider. A mostly self-trained press photographer, he took assignments for City Life magazine, and used his credentials to gain early access to venues like The Haçienda, the now-legendary nightclub that served as a nucleus for Manchester’s burgeoning rave scene, as well as many venues that came around the time such as the Boardwalk, Most Excellent, Legends, Precinct 13, Man Alive, The Thunderdome, and the Kitchen in Hulme. “The raving didn’t stop, there was always another party to go to,” Walsh recalls in an interview.

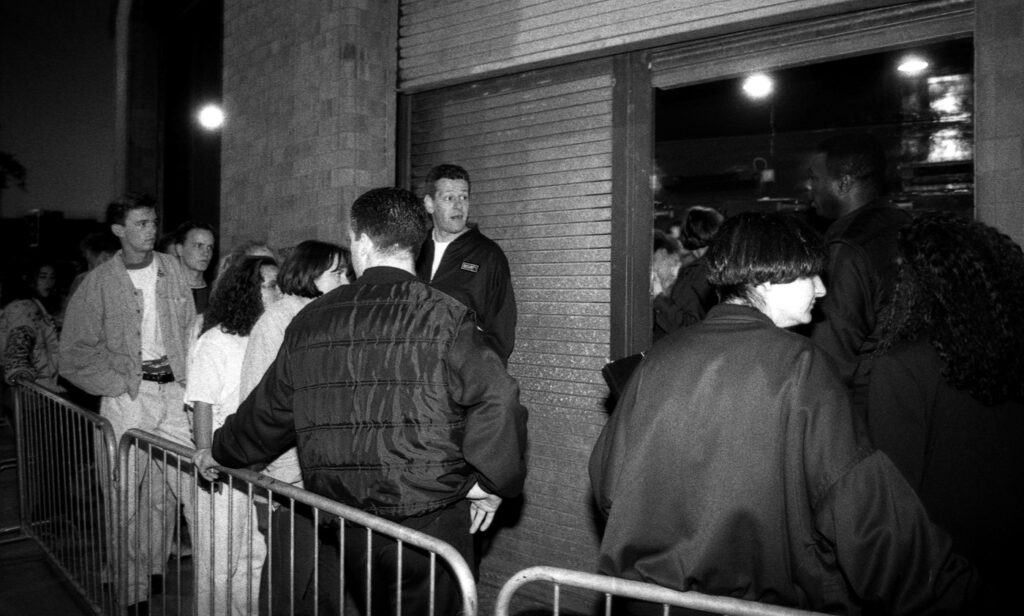

But his lens rarely lingered on the DJ booth. Walsh was more interested in the moments that others missed: the pre-club nerves in the queue, the security check past the door, the ecstatic blur on the dancefloor, and the ensuing comedown haze on the curb at dawn. “It was a significant moment. I wanted to photograph it for myself and not only for the magazines but documenting bouncers and the backstage and queues because it was a shifting culture.” Walsh says, “Something really big was going on here but they didn’t realise how big at the time. I knew it was important because growing up I used to watch a lot of documentaries like The Rolling Stones and see that counterculture happening so I could see that happening.”

For Walsh, The Haçienda in particular was iconic, in no small part for its groundbreaking design created by Ben Kelly, which Walsh describes as “so far ahead of its time” but also for its atmosphere, such that “each time you walked in, you were taken on a journey away from the drab, mainly rainy, dark streets of Manchester to a new and exciting space, where you would experience cutting edge music, visuals and people”.

Named after the quote from Ivan Chtcheglov’s Formulary for a New Urbanism, famous for becoming the slogan for the Situationist International, “The Hacienda Must Be Built,” the club’s reputation of openness and lack of pretentiousness attracted both regular people and local celebrities such as Peter Hook and Bernard Sumner of Joy Division/New Order. In addition to a cafeteria and several stages inviting music acts beyond the rave scene, the club hosted a hair salon and a cocktail bar downstairs called The Gay Traitor, named in honor of Anthony Blunt, an art historian who worked as a spy for the Soviet Union. At one point the German experimental band Einstürzende Neubauten came to perform with their trademark improvised instruments. True to form, part of the performance included drilling holes in the club’s walls.

From The Haçienda to the Alleyways: A Raw Archive of Rave Culture

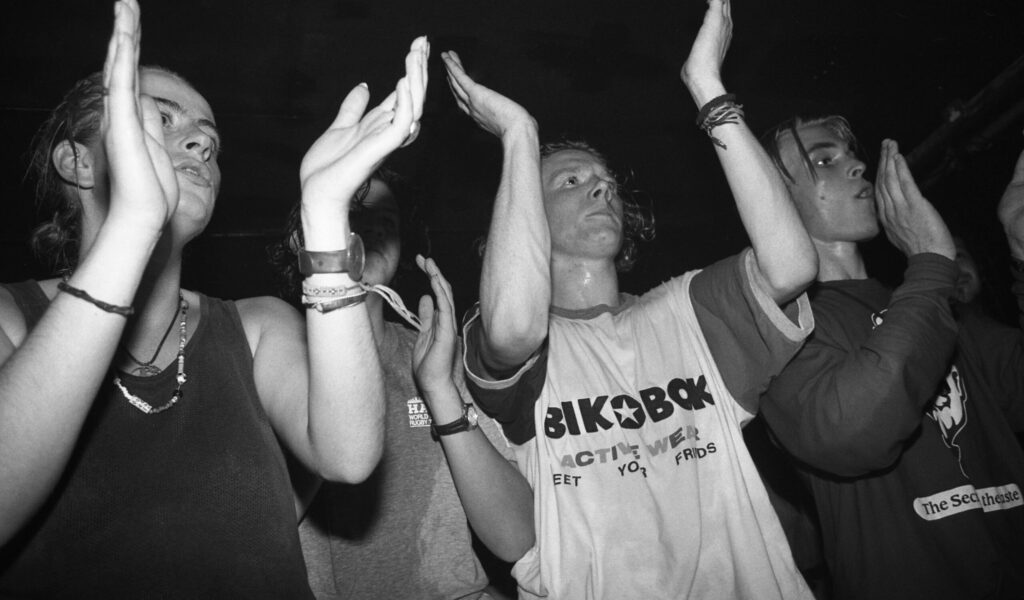

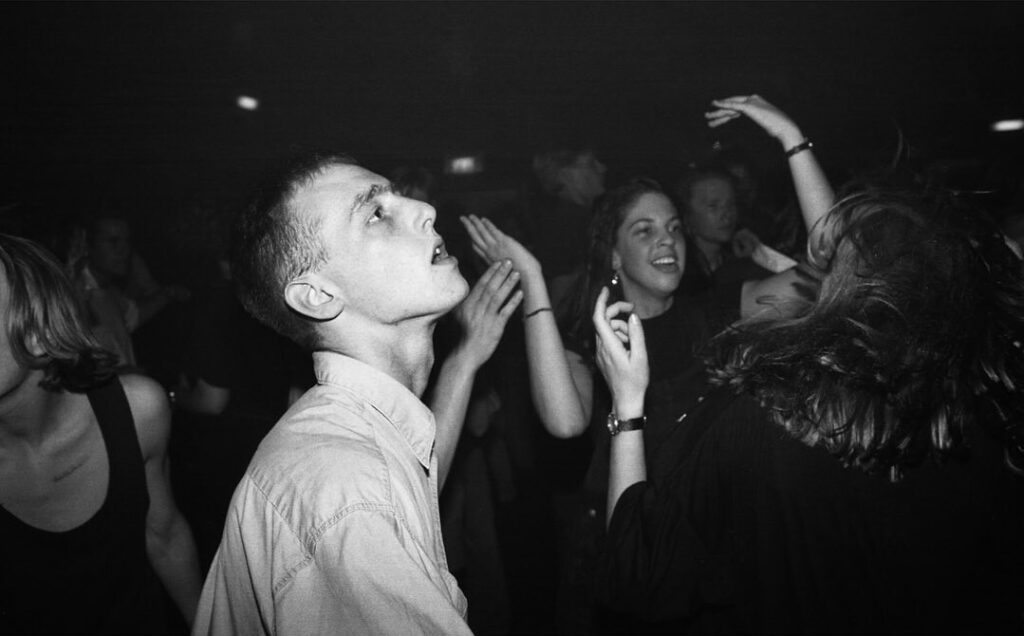

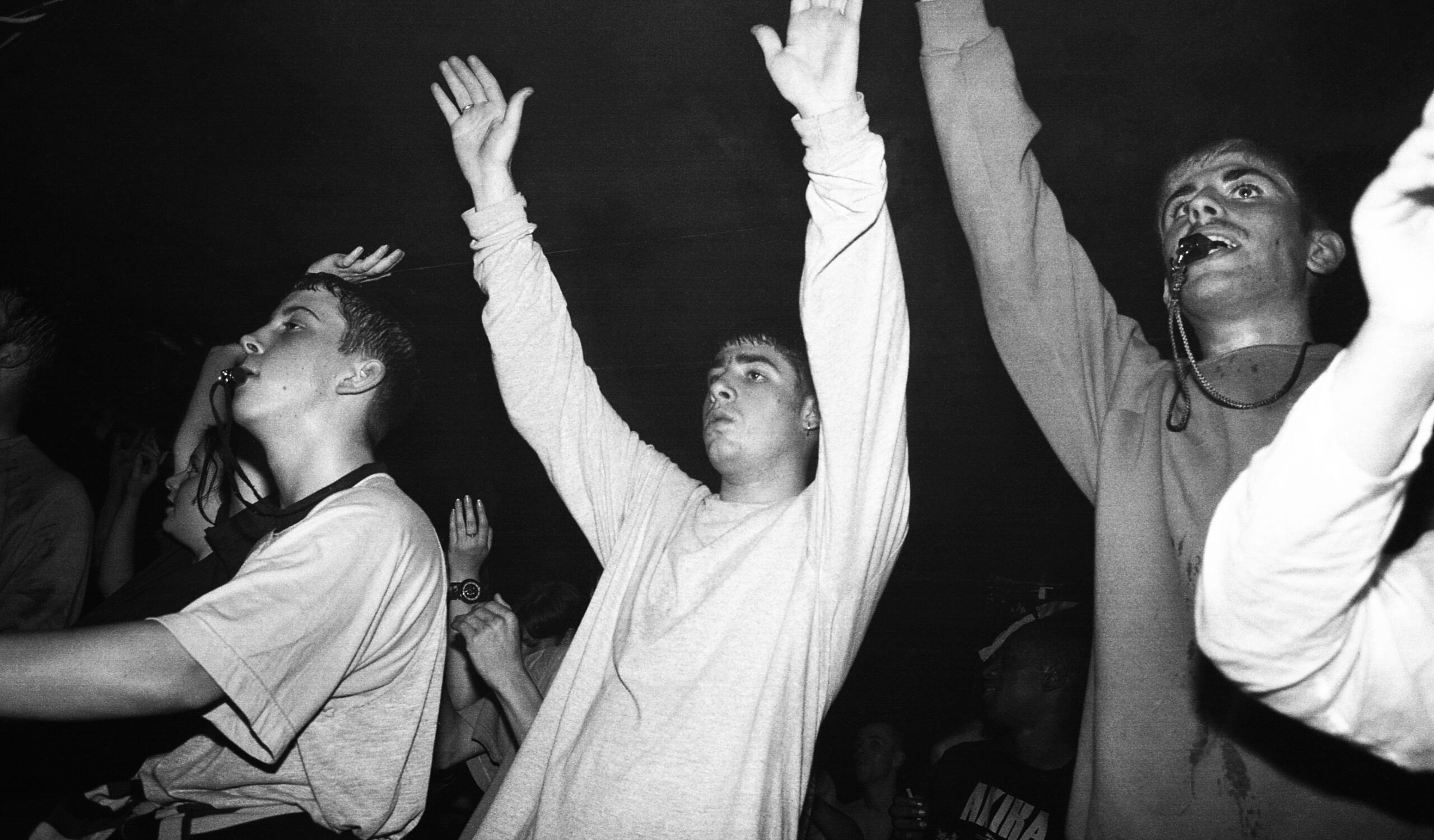

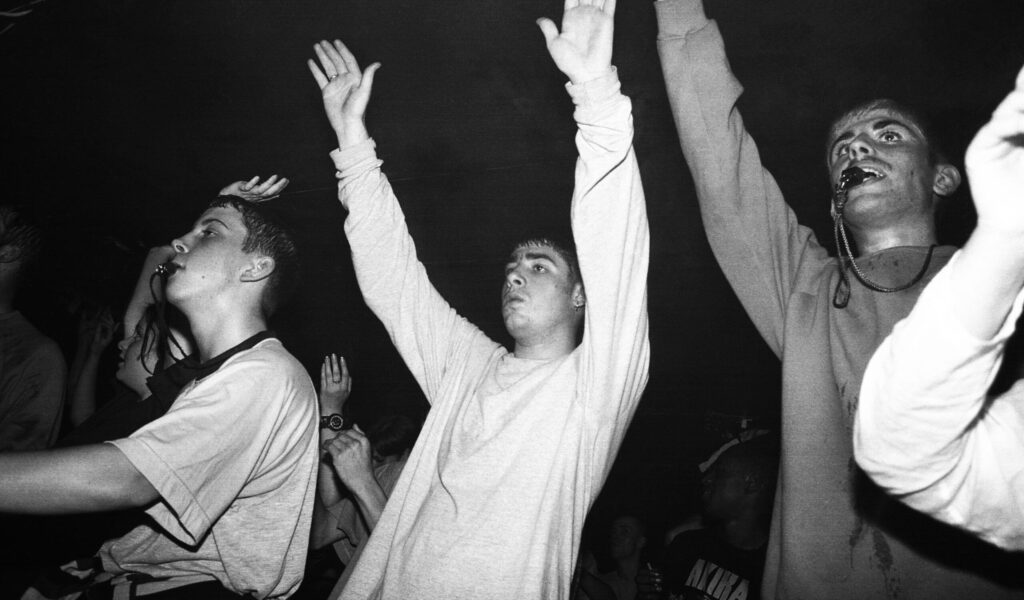

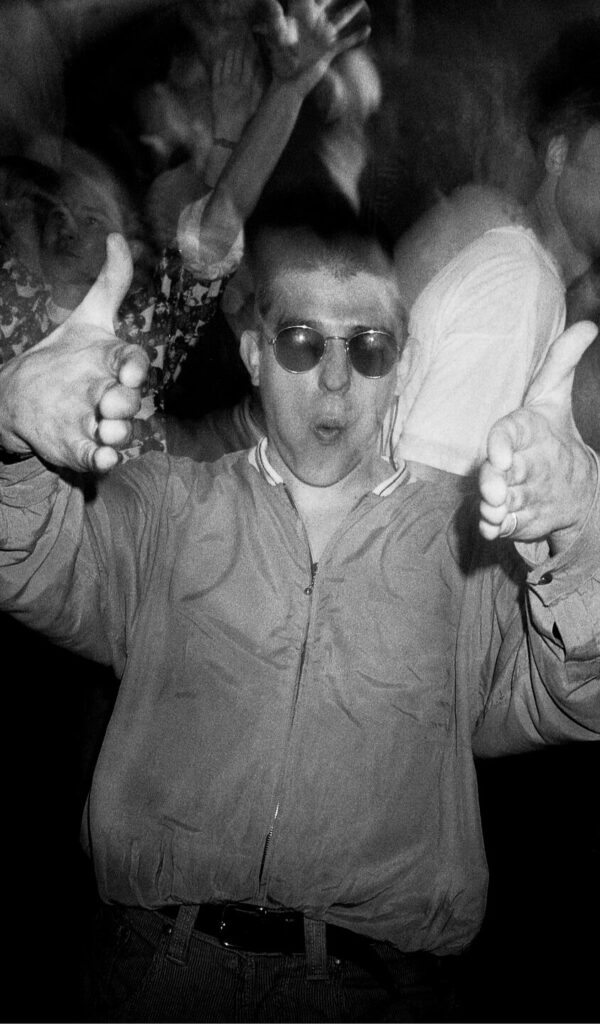

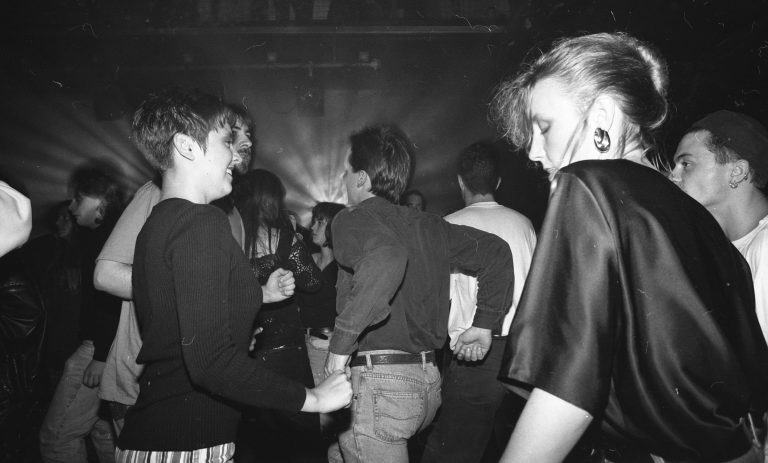

Shot almost entirely on black-and-white film and punctuated by the occasional color shots of piercing red and pink lights, RAVE ONE is a body of work defined by its proximity, immediacy, and complete lack of artifice. Walsh didn’t attempt to romanticize rave culture, he captured it as it was: ecstatic, chaotic, and sometimes rough around the edges. His photographs reveal a world teetering between euphoria and exhaustion, rebellion and ritual. In that sense, his work makes the experience almost universal, like it could have happened today and now, and we could have been there ourselves.

That honesty is exactly what sets RAVE ONE apart from other archival rave photography. The images don’t drip with retro nostalgia; they feel uncannily current, even now. There’s a visual rhythm in the series that echoes the music of the time: hypnotic, repetitive, with flashes of intensity. The photos show what it felt like to be inside a movement, not looking at it from afar. Ecstasy, both the drug and the emotional state, is rendered not through clichés but through moments: sweat-soaked shirts, wide-eyed joy, vacant stares under hot pink club lights. Walsh didn’t go out of his way to find hallmarks of the time either, the fashions people are wearing don’t always scream 90’s. Instead, they just look like things that average people from any time period would wear when they step out to have a good time. As Walsh remembers of the time: “If you went to other clubs in Manchester you had to wear a jacket, a shirt and a tie, and the culture was drinking with lads standing around the dancefloor and women dancing in the middle. You’d get fights because everyone was drunk. When you went to the Haçienda you could turn up in what you were wearing and the space was totally different to all other clubs.”

The Lost Years and Rediscovery

Walsh’s archive lay dormant for decades. Like many photographic works from a pre-digital world, the negatives were stored away, undervalued and largely unseen. But with a recent resurgence of interest in the roots of UK rave culture, and a broader reevaluation of the cultural contributions of the late 20th century underground, RAVE ONE has found a new audience.

In 2022, RAVE ONE was released as a 168-page photobook, published by IDEA Books, and quickly sold out. Critics and cultural historians praised the collection not just for its raw aesthetic, but for its anthropological value, a document of a youth movement that changed music, fashion, and nightlife forever. The project has since been exhibited at the Saatchi Gallery in London, the British Culture Archive in Manchester, and in independent galleries abroad, positioning Walsh as one of the most important documentarians of early UK rave culture. Currently, the project has found a home in London’s Museum of Youth Culture, the first institution of its kind anywhere, and due to open its doors to the public in October of this year.

Beyond the Clubs: A Snapshot of Societal Flux

More than just a party scene, Walsh’s work also hints at the deeper socio-political undercurrents of the time. The late ’80s in the UK were marked by high unemployment, the aftermath of the miners’ strikes, and Margaret Thatcher’s increasingly authoritarian grip. Rave culture, fueled by DIY ethics, pirate radio, and an anti-establishment attitude, emerged in part as a response to these conditions. Walsh mentions in several interviews that the scene was initially allowed to grow in part because the police had not yet understood exactly what was happening and were not yet sure how to crack down.

That all changed when the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, which famously attempted to criminalize gatherings featuring music “characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats,” came into effect, a direct governmental reaction to the power and popularity of the movement Walsh was capturing in real time. His photos unintentionally document the lead-up to a cultural crackdown, making them as politically significant as they are artistically.

A Living History

Today, RAVE ONE continues to resonate, not just as a historical archive, but as a reminder of the potential for joy, collectivity, and rebellion within youth culture. In an age where nightlife is increasingly commercialized, regulated, and surveilled, Walsh’s images are a testament to a fleeting moment of freedom: when thousands of young people transformed abandoned warehouses and industrial ruins into cathedrals of sound.

And that’s perhaps what makes RAVE ONE so enduring. It’s not just a record of what happened, it’s a portal into how it felt to be there, right in the thick of it, when the bass dropped and the boundaries of the night disappeared. Fortunately, the future is looking bright; rave music is more widespread than ever and Walsh still has unscanned film, reportedly numbering in the thousands, which he estimates could take at least a decade to process (if he has time between his current work as a videographer and photographer for publications such as Disco Pogo) so we may well see another few books to come out in the coming years.