Across the history of Renaissance Art, the mysterious Dutch printmaker Hercules Seghers is perhaps the most innovative–and relatively unknown.

There are some artists that, for whatever reason, were years ahead of their time. When it comes to the Dutch Renaissance, the mysteriously experimental Hercules Seghers was arguably centuries ahead of his contemporaries. Specifically, some two centuries ahead. Like many clear geniuses of the art world known to us today, Seghers was relatively unknown to most people until the last century. Today, he inspires many visionaries in the art field and beyond, such as Werner Herzog, who once dubbed him the “father of modernity.”

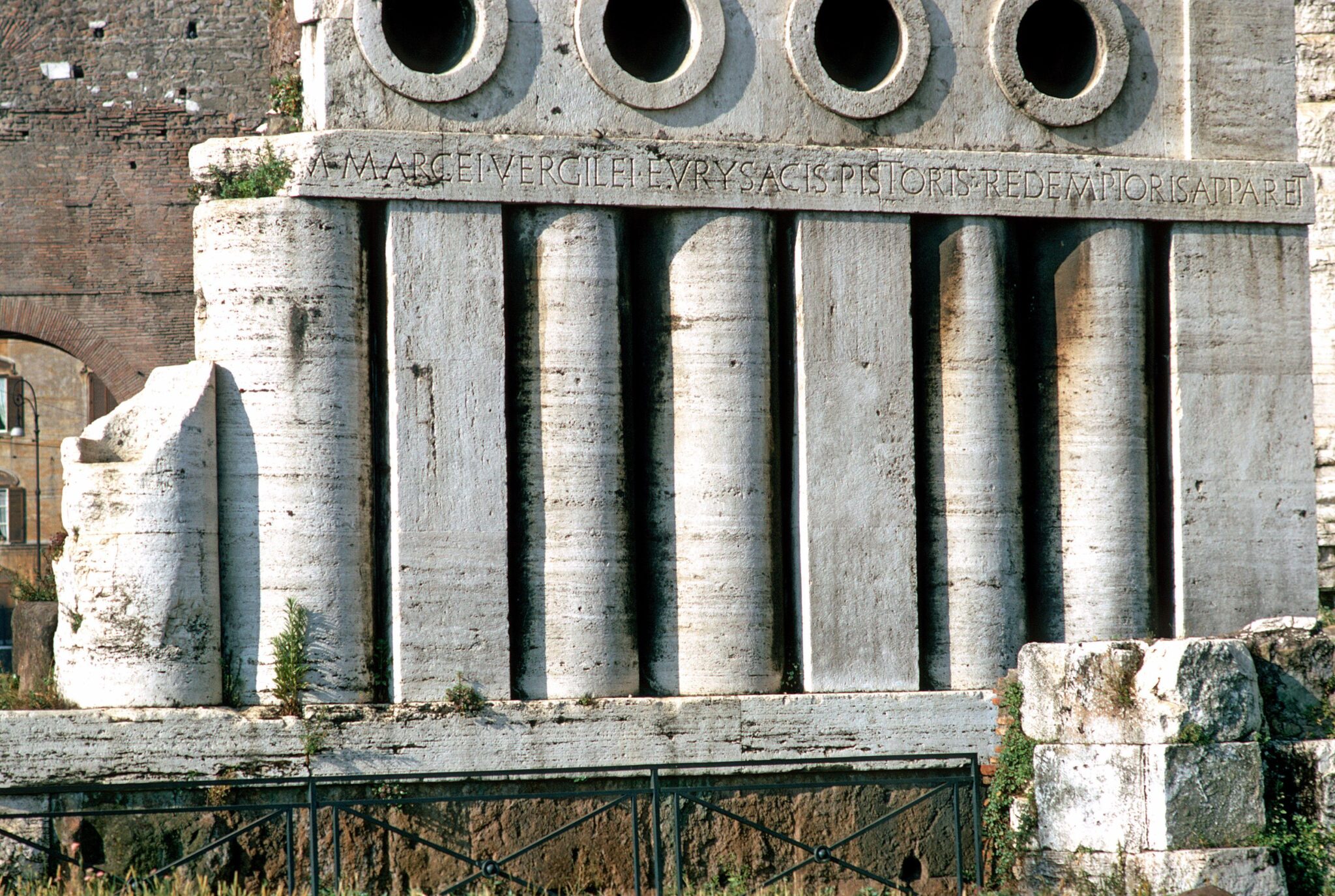

The Tomb of the Horatii and Curiatii, ca. 1628–29 © Rijksmuseum

He’s been seen as avant-garde before there was traditionally such a label, described as the “forerunner of Surrealism” by art historian Heinz Spielmann, and compared in varying degrees to the romanticists and later modernist artists. One look at his works will tell you why. Like other artistic innovators of the time, Seghers believed in depicting life and nature through his own understandings instead of attempting to depict them exactly as they appear in real life, this resulted in a simple view from the window of his house in the middle of a town being transformed into a rocky landscape.

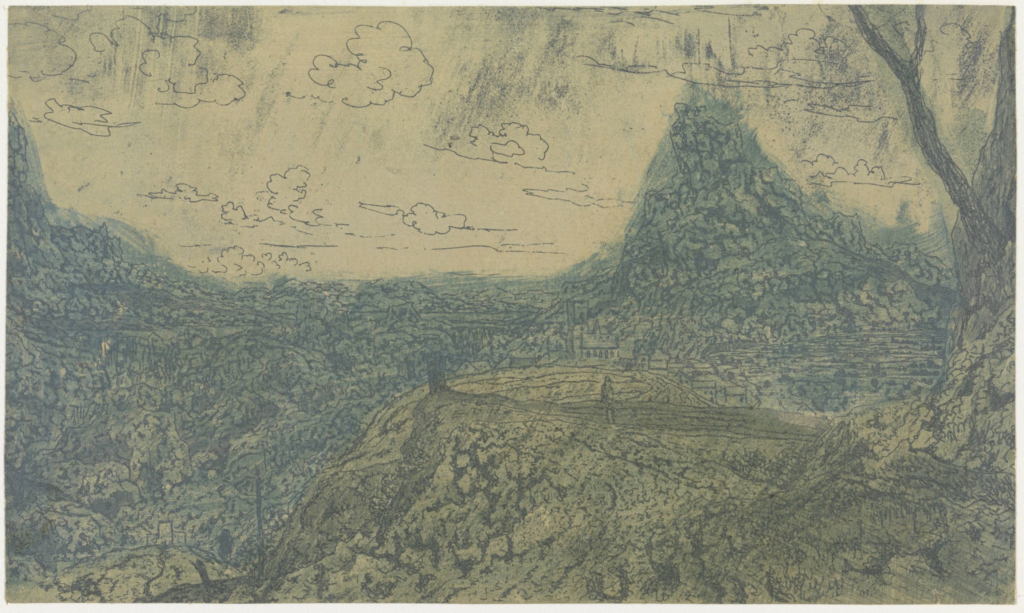

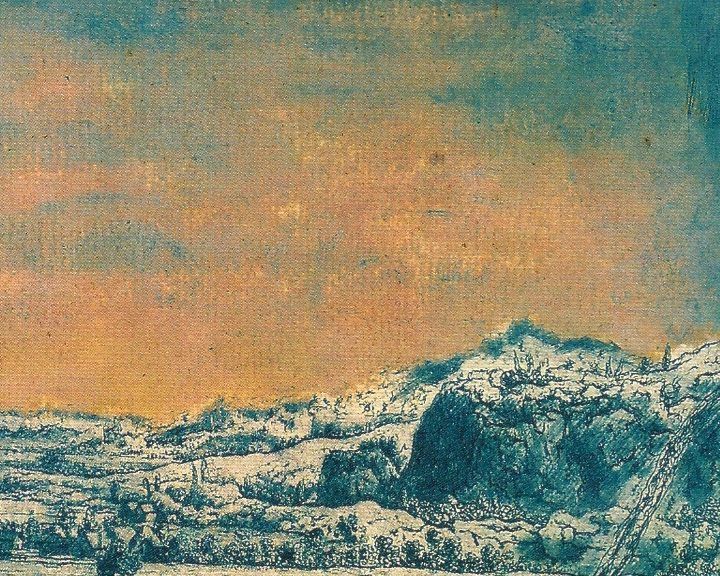

Rocky Mountains with a Plateau, c. 1625–1630 © Rijksmuseum

Furthermore, Seghers created sublimely exotic vistas of dense mountainous, untamed lands seemingly far beyond the reaches of the below-sea-level flatlands of the Netherlands — despite never having gone farther than Brussels. In his works, cityscapes are sometimes replaced with swathes of trees, rugged and towering rock forms are set down in places they could never be in, and Roman ruins are depicted in settings far away from their actual homes. This is what makes Seghers’ subject matter so unique from typical landscape art of the time, it was a middle ground between imagination and representation, representing the fantastical sense that would reappear on a grander scale during the Romantic period of the early 19th century.

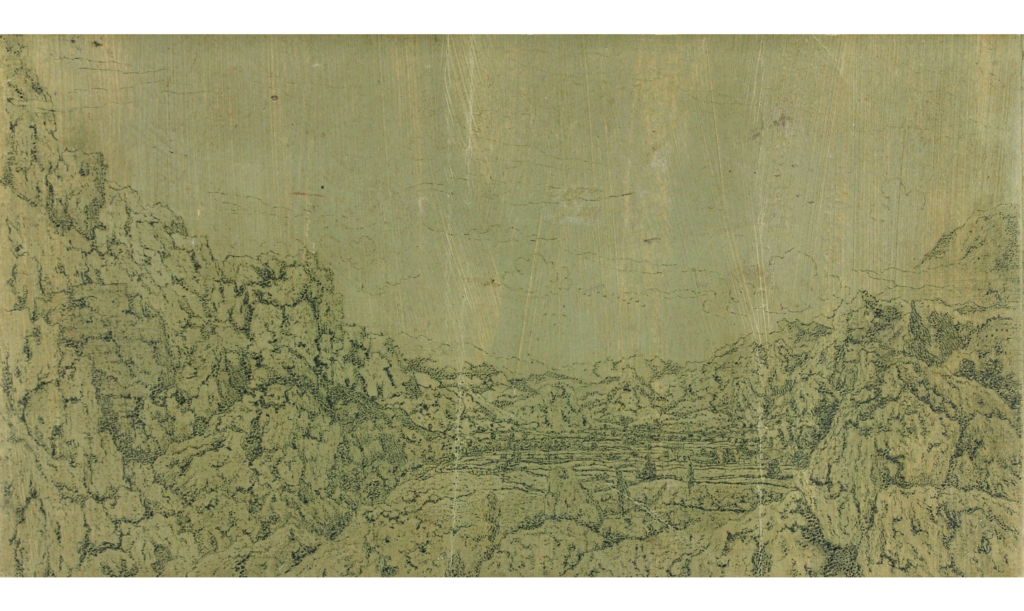

Mountain Landscape with a Crest, First Version (left) and Second Version (right), c. 1622–1625 © Rijksmuseum

While Seghers is known to have been a painter in his own right — having made at least eighteen works, with six only recently having been identified after research was done on around 100 works suspected to be made by him — he is specifically known for his groundbreaking prints, which were rather accurately described by fellow artist and art historian Samuel van Hoogstraten as “printed paintings” in reflection of the fact that Seghers made every print of his unique by eschewing the strictly duotone aesthetics of Dutch printmaking and using a mixture of oils and watercolors to personally paint over each print in different colors, resulting in drastically different moods and time of day in each of the prints, predating the pop art experiments of Andy Warhol by three centuries. For example, Distant View with a Road and Mossy Branches was created in eight different versions alone.

Since no two prints ended up looking the same, this was a total subversion of a burgeoning printmaking trade of the time that commercialized art by making multiple copies of the same piece available for purchase (sometimes in quantities of up to several thousand), creating a hybrid of traditional painting and printmaking, and rejecting the idea that all prints from the same plate should be exactly the same, an event accurately described by one critic as “A Post-Modernist act committed in a pre-Modernist era.” This was a first for the era and nothing so experimental had occurred in the world of European printmaking until the late 19th century — around the same time, Seghers was rediscovered in various European art circles, coincidentally enough.

Two decades before his contemporary Rembrandt had begun using it in 1647, Seghers is known as the first European artist to have used Japanese paper and continued experimenting with other mediums to print his work on such as burlap, linen fabric from tablecloths, and even his marital bedsheets — a choice his wife was surely not happy about. Whenever he did use paper, he often colored it using his own treatments rather than using pre-colored paper which was readily available, and this sometimes resulted in his most experimental works, such as the particularly mysterious Ship in Rough Water which was printed on a dark brown background using white ink.

Ship in Rough Water, c. 1625–1630 © Rijksmuseum

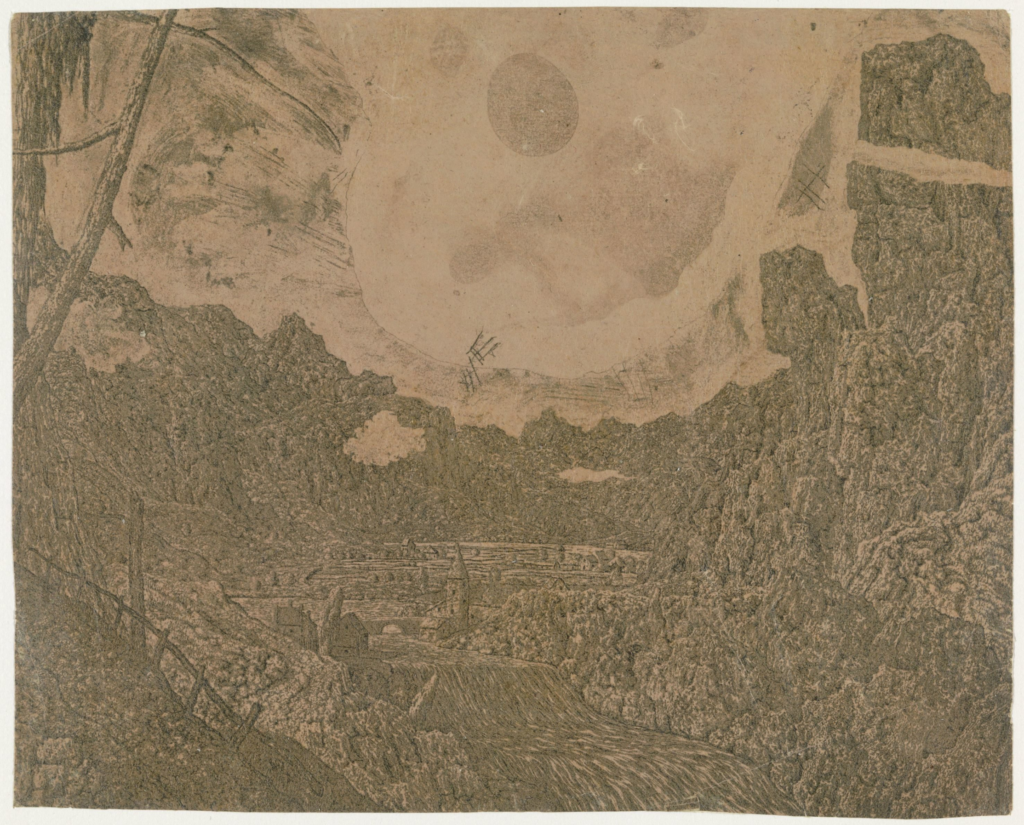

Seghers was even known to have recycled his earlier works into new prints by etching over them, visible in Rocky Landscape with a Gorge where the ghostly rigging of a ship appears in the background — a fragment of a larger, unfinished depiction of a ship that Seghers evidently abandoned — but ultimately appearing as something reminiscent of a double-exposed photograph. This innovation was surely not immediately accepted, but it did generate a wholly new visual effect.

Rocky Landscape with a Gorge (First Version), c. 1625–1630 © Rijksmuseum

This reuse of etching plates was not exclusive to him, as Rembrandt had even bought a landscape etching plate after Seghers had died and repurposed it for one of his own works a decade later. Seghers’ Tobias and the Angel, a scene from the biblical Book of Tobit was edited to remove the figures, leaving only the landscape, and then used as the backdrop for Rembrandt’s Flight into Egypt, depicting a scene from the life of Christ. This is perhaps the biggest endorsement of Seghers’ worth as an artist and at least some proof that he was appreciated during his time and that Rembrandt loved and was at least somewhat influenced by Seghers, with some of the latter’s works even having been wrongly attributed to Rembrandt at one point.

Rest on the Flight into Egypt, c. 1653 (right) © Rijksmuseum

Surprisingly, even technical mistakes were incorporated into the finished works or what is known to some artists today as the “happy accident”. In many of Seghers’ works, you will find oddly textured effects in the sky or elsewhere, sometimes these are areas where Seghers scratched the plate from testing his hatching technique while in other works there are stray acid markings and blotting left over from an imperfect application of the print to the medium, an effect known as “foul biting”.

Rocky Landscape with a Road and a River, c. 1622–1625, First Version (left) and Second Version (right) © Rijksmuseum

While other artists would discard the misprinted results, Seghers deftly worked them into his landscapes to pass them off as streaks of clouds or atmospheric effects of some kind or another. Sometimes, he purposely seemed to have used faulty or compromised etching plates which either resulted in scratches from unpolished plates being transferred over or other effects not intended to be visible in the finished work. Whether he intended to or not, Seghers never corrected these mistakes and appeared to have tried to use them to his advantage. Again, a practice that would be unacceptable for the many fastidious fellow artists of Seghers’ time.

Valley with a River and a Town with Four Towers, c. 1626–1627 © Rijksmuseum

Seghers can also be credited with inventing an entirely new way to create prints. Interchangeably called the “lift-ground” or “sugar-bite” method of etching, the process allowed the artist to create a composition on the etching plate using a mixed solution of ink, cold water, and sugar instead of the traditional method of using a needle. The design would then be coated in an acid-resistant wax, and bathed in hot water before being transferred to paper in the same way as regular prints. The resulting effect appears granulated and textured using this method.

Seghers evidently had no students, this technique died along with him and wasn’t rediscovered until the end of the 18th century by English printmaker Alexander Cozens. On other prints Seghers experimented with making print impressions using leftover ink on a plate (resulting in a lighter, partial print) and by pressing a plate on cloth or paper and transferring that impression to a third medium so the final result would be reversed, facing the same way as the design on the plate, a technique known as the counter-proof.

It may be clear that many of these innovations are seemingly economical in their approach, and this appears to be no coincidence. In life, Seghers was notably impoverished. His reuse of copper plates, acceptance of unorthodox mediums for printing, and adoption of printing errors into the works were done out of necessity and lack of resources, say some scholars. If this is indeed the case, it’s nothing to discredit the originality of his visual techniques, but it does serve as a commentary on the relationship of artists with poverty. Seghers’ financial position was no secret either, as he was squarely mentioned in Hoogstraten’s book, in the delicately titled ‘How an Artist Should Conduct Himself in the Face of Fortune’s Blows’ and described as having been “murdered by poverty … because of the one-sidedness of supposed art connoisseurs.”

The use of paint over printed matter itself, the style characteristic to Seghers, may be done in response to the growing demand for affordable landscape paintings, believes Huigen Leeflang, curator of prints at the Rijksmuseum, he also points to the fact that several of Seghers’ prints were made on canvas, which is traditionally reserved for oil paintings. Certainly, as an art dealer himself, Seghers was no doubt keenly aware of the demands of the commercial art market of the time.

Whatever could be said for the life of the hand behind these visionary ideas, there is little biographical data to work from, and whatever is available comes mostly from the writings of the art chronicler Samuel van Hoogstraten, who published his ‘Introduction to the Academy of Painting, or the Visible World’ in 1687 and included information about various figures in the Dutch art world using information he learned while working as an apprentice to Rembrandt. Despite it being the only specific source related to Seghers, the information is likely based on rumor (based on the fact that he was just barely entering young adulthood when Seghers died) and seldom definitively confirmed by scholars.

Around 1589–90, Hercules Pieterszoon Seghers was born into the Haarlem Mennonite family of Pieter and Cathalijntgen Seghers. the son of a textile merchant, he did not take on the trade and instead went to apprentice under the landscape painter Gillis van Coninxloo in Amsterdam, sometime after he arrived in the city with his family in the years of 1592–96. His master belonged to the mannerist school — a style best exemplified by the painter El Greco — where refusal to create exact depictions of reality and aversion to traditional norms of painting defined the style. It was likely this influence sparked Seghers’ artistic direction. The apprenticeship was cut short around the age of 16 following Coninxloo’s death in 1606.

Seghers and his economically-minded father bought much of the contents from the late painter’s studio, presumably to resell at a higher value later on. Seghers remained in Amsterdam until his father died in 1612, after which he returned to his hometown of Haarlem and was registered as a master at the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke, a Christian artists’ trade union that was quite influential at the time.

Two years later at the age of 24, he returned to Amsterdam to receive custody of an illegitimate daughter and in the year after that married Anneke van der Brugghen, a wealthy woman 16 years his senior on 10 January 1615, in the town of Sloterdijk, north of Amsterdam. While they were not known to have had children together, they did raise Seghers’ daughter together. Five years later on 14 May 1619, he took out a mortgage on a sizable home in the Jordaan neighborhood of Amsterdam for the price of 4,000 guilders, which was not a small sum for the time.

It was by this point that Seghers began to have financial troubles. Several years after he purchased his home, he had accumulated debt, selling the house and a collection of around 138 paintings in 1631 before moving to Utrecht and attempting to become a dealer of his and other art without much success. In 1633, he moved to the Hague where he stayed until the end of his life. By this point, there is nothing certain about this period other than rumors that he fell into depression, took to drinking (probably as a result of his misfortunes), lost his wife, and took on a new one shortly after, as a person by the name of Cornelia de Witte was listed as widowed to “Hercules Pietersz” in historic documents.

Seghers died sometime before or in 1640, at best around the age of 49, and the circumstances of his premature death are not entirely clear. Researchers again look to Hoogstraten, who claimed Seghers had died after falling down a set of stairs amid a drunken stupor, but there is no way to verify this claim. Nevertheless, this event may serve as an explanation as to why many of the prints that made their way into the hands of various collectors after Seghers’ death appear to be unfinished or experimental.

In life and the decades immediately following his death, Seghers was understood to be an artist who toiled in obscurity and poverty, and he did not seem to sell enough of his works to remain financially stable, let alone attract interest in casual buyers. Hoogstraten’s writings even mention that Seghers’ prints were so under-appreciated at the time that they were “used to wrap butter and soap”. That is not to say he didn’t have his share of appreciators, and an artist of the time could not have had a better admirer than the esteemed Rembrandt, who acquired eight of his paintings.

Like many mysterious historical figures, in the absence of historical facts, many have created theories surrounding Seghers’ work. One such theory holds that Seghers was heavily influenced by Chinese ink landscapes and sought to replicate them in his work, which is known for its mysterious, mountainous landscapes and delicately minimal depictions of trees and brush. Scholars have pointed to his early adoption of Japanese paper — a product imported from the Far East to the Netherlands as early as 1609 — as evidence of his intercultural savvy.

Seghers’ background as an art dealer no doubt meant that he was at least aware of the popularity of Asian art at a time when trade between the Japanese and Dutch was at a historic high, but curators and many historians still reject the theory due to the absence of any concrete link, although this notion reappears throughout many art movements in Europe in the centuries since and would be by no means unique or out of the ordinary for a man such as Seghers.

Many art historians are also quick to suggest that he may not fit the archetypal starving artist category as well as previously thought. Following his death, one man, Michiel van Hinloopen, enjoyed Seghers’ work enough to purchase 40 of his works from his estate, suggesting they were sought after to some degree. The works in museum collections descend from this postmortem sale of his works, and museum experts are unsure whether their appearance looks as Seghers intended them to be or if they were his unfinished works still awaiting to be fully colored and corrected. Many cast doubt on the idea that the unprofessionally modern appearance of the prints was the full intention of their creator.

But for many long centuries, Seghers was an artist lost to history. Now he is finding newfound recognition in some of the most prominent institutions across the West. In 2012, the British Museum ran a small exhibition of their collection of his works, while a touring exhibition began at the Rijksmuseum and made its way a year later to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

The appeal is immediately clear, to paint from the imagination when the tradition was to paint from life is outstanding on its own merits, but there is something pensive about his landscapes that leads us to set Seghers apart from the rest. Seghers was not prone to depict people, there are no surviving portraits by him, and any depictions of human figures usually only served as minor decorations to a larger scene, always dwarfed by the titanic creations of mother nature, and it seemed that he preferred to keep people at a distance when it came to his art, and focus on nature’s grandeur alone. Naturally, the proto-surrealist Pieter Bruegel the Elder is known to have been a great influence on him, and at least one work of his was based on a print made by the renowned German mannerist Hans Baldung Grien.

There are pieces such as Castle with Tall Towers, in which some parts of the landscape are depicted only through a series of clustered dots, arguably predating the style of pointillism developed during the age of Impressionism. In his mind, he was a traveler and his work reflected that, depicting various regions far from the lowlands he called home, Hoogstraten aptly remarks “It was as if he were pregnant with whole provinces.”

Seghers made several prints of religious scenes and still life, the most striking is a vanitas skull depicted in the same style as his cliffs, grotesquely intricate and seemingly conveying a feeling of dread and resembling more of a sculpture than anything usually seen from the artist. Another print depicts a stack of sagging, tawdry books, haphazardly piled on top of each other and opened to random pages, as if someone had been frantically reading them and heavily scrutinizing their contents before leaving in a hurry, the books left frozen in the middle of the act. This work is unique not only for Seghers but for art history as a whole, as art historians say this is one of the earliest depictions of still life in print form–the medium had been dominated almost entirely by landscapes at the time.

Historians suggest that other contemporaries beyond Rembrandt were aware of Seghers and imitated his style, such as Jan Ruyscher, whose alias was “De Jong Hercules” (The Young Hercules). The influence is also clearly seen in the coming centuries, particularly in the heavily experimental art movements that grew in post-WWII Europe. Modern printmakers in the Netherlands from Willem Van Leusden (who studied and wrote an entire book on Seghers’ technique) to Frans Pannekoek and Charles Donker are cited by one study as carrying on the methods of Seghers into our times.

On their own, the haggard cliff textures envisioned by Seghers, unique for their intense complexity, inspired many future works of art. Surrealist Max Ernst, sought to depict the same type of craggy, coral-like cliffs in his own works and was established to have specifically looked to Seghers as a visual source. In fact, textures like these are almost so ubiquitous now that we’re probably not even aware of the full extent of how radical such art was for the time.

For an artist whose surviving body of work — a total of a handful of paintings and less than 200 prints from around 50 copper plates — was even smaller than that of the elusive Vermeer (one painting was only fairly recently lost in a museum fire in 2007) and surprisingly little is known of the stories behind them. Not even a chronological ordering of his work is possible as Seghers didn’t date or sign his works, which led experts to go as far as to examine the tree rings inside the wooden frames accompanying his works to determine any approximate dates. It is believed there are certainly far more works of his to discover, perhaps lost to time, but the few that exist with us today are immensely captivating, the product of a single imagination that toed a fine line between elegance and provocation.

Mountainous Landscape, c. 1650 (destroyed by fire in 2007)

Werner Herzog, who dedicated an essay to Seghers, captures his reclusive essence best, he writes: “His images are hearsay of the soul. They are searchlights, or rather an ominous, frightened light opening breaches into the recesses of our self. It is like a hypnotic vortex pulling us down to the bottom of a bottomless pit, to a place that seems somewhat known to us: ourselves. We morph with these images.” Indeed, Hercules Seghers is a challenging artist who is only now receiving his fair share of credit, and whether he intended to do so or not, he laid out the path for centuries of further experimentation and artistic innovation.