Art collector Désiré Feuerle has spent a lifetime dissolving the boundaries between ancient and contemporary Asian art. Having transformed an old wartime bunker into one of Berlin’s most contemplative museums, he hopes to present his vision of art not as a series of timelines, but as a dialogue across centuries.

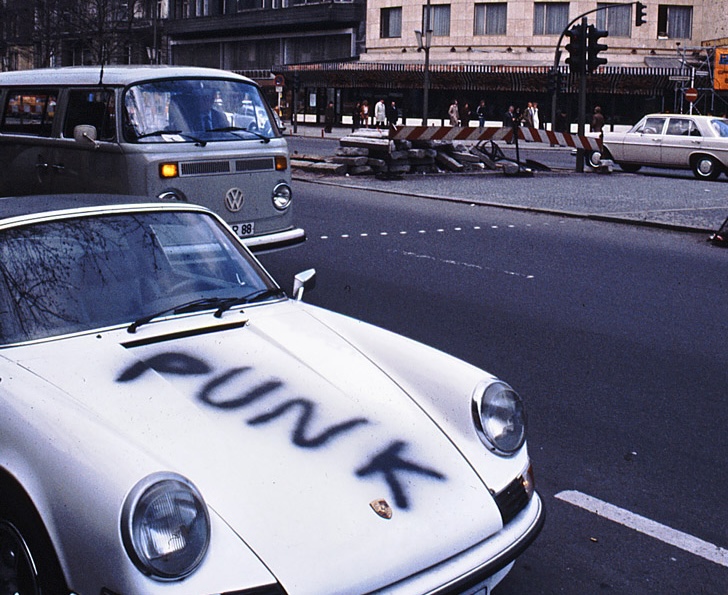

Even after eighty years, Berlin maintains a unique connection with its bunkers. Originally built to withstand bombings, these concrete structures, both monumentally evocative and hauntingly confined, have become unlikely havens for art and culture, particularly the city’s renowned rave scene. The dark underground, both literal and symbolic, has long served as fertile ground for musical and cultural innovation.

As recently as 2008, this format took a new turn with the opening of the Boros Collection, housed in the renovated Reichsbahnbunker in Berlin-Mitte, a space that once hosted raves. Yet the concept of using bunkers to house and exhibit art remains largely unexplored. One of Germany’s foremost private collectors, Désiré Feuerle, is now boldly venturing into that territory, carefully chiseling out a path that others may soon follow. But what is it about this museum, beyond its strikingly unconventional setting, that has recently begun to resonate so deeply with Berliners? And why Berlin of all places?

A Timeless Dialogue

Since opening its reinforced steel doors to the public in 2016, the Feuerle Collection remains one of the most daring visions for what a museum space must look and feel like to the visitor. It’s a space with not many pieces of art in it at all, and yet visitors regularly return, many experiencing something new with every visit.

The museum puts Feuerle’s piercingly acute vision of what he finds to be beautiful on view, in the form of Imperial Chinese stone and lacquer furniture (from as early as 200 BC all the way to the 18th century) and early Khmer sculptures (spanning the 7th to 13th centuries), which are displayed and contrasted with various pieces of contemporary art from the West and Asia in the interest of creating a conversation between places, time periods, and cultures. Feuerle’s roster includes readily known names such as the British-Indian sculptor Anish Kapoor and transgressive Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, but also less immediately recognized names such as the photographer Adam Fuss, conceptual artist James Lee Byars, sculptor Cristina Iglesias, and painter Zeng Fanzhi.

Art as Atmosphere

Although the works share a single display hall and striking contrasts of period and style arise from their juxtaposition, this is far from a careless mashup of ideas. The museum’s infamously meticulous owner demands an experience that must be felt to be believed. Each piece is spaced with solemn grandeur and illuminated by carefully calibrated lighting, precisely adjusted in placement, tone, and brightness for every individual work. This careful curation suggests that each object tells a profound story through emotion alone, with all distractions minimized or removed entirely.

Accordingly, the Feuerle Collection offers no information labels beside the art, and visitors are encouraged to silence or leave their devices at the door. Crucially, the collection itself is a gesamtkunstwerk: a total work of art, an ever-evolving, synesthetic environment meant to be experienced intuitively rather than analyzed, beginning with the building itself.

A Meeting of Minds

The collection is located in one of West Berlin’s most well-known arts districts, Kreuzberg, which was once one of the most impoverished quarters of the city prior to the fall of the wall. It sits in an unassuming space between a disheveled public park, the waters of the Landswehr Canal, and a property development office. As a local, you could easily walk by the Feuerle collection several times before discovering it was open to the public, it’s only marker being the subtle application of the museum’s name in black and red letters on its concrete facade. Once known to locals as the BASA Bunker, the 6,500 square meter space consists of two bunkers created in 1943 and intended to serve as a wartime base of telecommunications for the national railway system, the Deutsche Reichsbahn, but the war ended before it could be put into use.

Save for its occasional function as an impromptu rave venue (this is Berlin, after all), it sat vacant for decades until It was finally acquired by Désiré Feuerle in 2011. Upon seeing the windowless, underground hall, accented with only two rows of thick load-bearing columns, a distinct vision for the space came to him, and for nearly a year he set about searching for the right collaborator to bring his vision to reality. That partnership was reached upon his meeting with the renowned architect John Pawson, known for his appreciation of minimalism, raw materials, and recontextualizing historical spaces.

Pawson has designed or renovated everything from monasteries and 13th century cathedrals to operatic set designs and sailboats, but this would be his first project in Berlin. According to Feuerle, as soon as the two met to discuss the project, a shared understanding was reached between the two of them in “about five minutes”.

Embracing Raw Architecture

Over the course of the next five years, Feuerle, Pawson, and a team of architectural firms that included Petra Peterssons’s Realarchitektur (most famous for their renovation of the aforementioned Reichsbahnbunker which now houses the Boros Collection), undertook an unconventional renovation of the bunker.

“I knew from the beginning when I visited the site and first had that visceral experience of mass that I wanted to use as light a hand as possible,” Pawson recalls in his website’s journal, “Concentrating all the effort on making pristine surfaces would never have felt appropriate here. Instead this has been a slow, considered process – a series of subtle refinements and interventions that intensify the quality of the space, so that all the attention focuses on the art.” On several other occasions, Pawson has likened the bunker to the engineers’ architecture praised by Donald Judd, the kind of utilitarian work created by engineers for civic and industry use which nonetheless takes on a certain unique beauty of its own over time.

Darkness by Design

The bunker’s lower floor was found in a state of total disrepair, with the entire floor having being flooded and covered in leaves, stalactites having formed on the ceiling, and pitch black darkness, as if they were presented with a purely negative space, a void from which they were tasked to bring something into existence. In the process of renovation, it was important to all parties that each period of the building’s history, no matter how slight, was preserved in some measure, accounting for each detail and idiosyncrasy almost as if they, too, were individual pieces in a museum’s inventory.

The changes were slight: white walls were introduced on the ground floor, the concrete was cleaned, cracks were sealed, but many interventions of nature were nonetheless preserved. The staining from water seepage and stalactites were kept in their places. Signs of human presence, too, were sustained: a solid stripe of green paint from the era when this was a government institution, graffiti and fire marks from long-forgotten raves, and even a group of long chains, left hanging for no specific purpose. The lack of any natural light coming into the building meant that darkness would be worked into its favor, transforming the space from one of wartime defensiveness or renegade secrecy into peaceful, quiet contemplation. For Pawson, the biggest hurdles of this project had to do with engineering, likening the issues to “trying to put heating in the pyramids.”

Art Beyond Explanation

It’s worth reiterating that this was all done in order to display but a portion of one man’s art collection, but it is nonetheless open to the public by appointment, and where the hand of the architect left off, Feuerle’s work continues, and it is by no means any less precise in its intent. Your experience as a visitor begins when the museum’s employees, donning black silk jackets, custom-made by a designer in Taiwan, open the door and escort you down into the bunker’s lower level. As soon as the door is shut, you find yourself engulfed in pitch darkness, after which you are treated to a recording of John Cage’s Music for Piano No. 20, officially signaling the beginning of your experience in the collection. Meditative in its approach, it is intended as a means to reset the senses, distance you from the noise and bustle of life above ground, and direct your attention to the art that is to come. The thickness of the museum’s walls prevent any chance of mobile phone reception, so you can be assured that you will not be distracted by a random notification while you remain down below.

As you become accustomed to the silence and darkness, a vague glow appears at the edge of the room, you are then directed to slowly approach this light, which leads you to the main room. As you enter the exhibition hall, you are greeted with the sight of Khmer sculptures, fluid and smooth in their rendering, captured in the moment of effortless motion. There is a thousand-year-old head of a Khmer warrior, uncannily modern in his essence, with jewelry hanging from his ears and a braided hairstyle that would not be totally out of place to encounter among the trendy passerby’s in the streets above. Further on, other figures are on display, next to photographs on the walls. Again, there are no labels for any of the works, only the aid of the museum’s guides should you have any questions, answers whispered back to you in hushed tones in order to preserve the quasi-monastic silence of the space.

As you continue on, you will not miss the attention to detail when it comes to the lighting. While sparse, it is ingeniously precise, casting just the right amount on each piece to emphasize the full essence of the work. With no windows, skylights, or other sources of natural light, the zero point of the space is total darkness, which implies a certain totality when it comes to controlling light, and it is this approach that allows this elemental function, essential to our perception of any visual medium, to be finely tuned to each individual piece. Just as there are spots in the room with no light, there are no works on display there either, and in time your expectation of both becomes intertwined, as if down in this room, the presence of art naturally makes light appear.

The Mission of Connection

This is all, of course, part of Feuerle’s holistic approach to experiencing art, where he elevates feeling and engaging with the art (sometimes one piece for hours at a time) over purely studying it as an artifact, understanding its historical context, possessing a certain background of knowledge before entering the space, and so forth. For the Khmer pieces in his collection, Feuerle has noted on several occasions that he believes the art is shaped by stomach and gut feeling, whereas the Chinese works further ahead in his collection come from the mind, underlining the differences between the two cultures and their respective approaches to art. It is for the sake of this dialogue that the Feuerle Collection exists in the first place, and it is a dynamic and ever-changing dialogue, as the works here are moved and rearranged on a semi-regular basis.

A perfect example is seen in the combination of a Khmer sculpture of a deity belonging to the Hindu tradition (Cambodia was a major center of Hinduism outside of India until the 14th century) and a contemporary steel sculpture by British-Indian artist Anish Kapoor. While one work was produced centuries ago in Asia and made with a clear reverence for religious tradition, the other was created recently in the West and instead focuses on a material view of the world. Kapoor, whose father’s side of the family is from India, a nominally Hindu culture, was brought up in a household that did not center around any religious values at all. The opportunity to contrast the two works is interesting if you come with this context already in mind, but merely observing the works as they are will stimulate a conversation all of its own, and this can be said to be Feuerle’s entire mission.

Provocative Pairings

The Feuerle Collection’s other area of specialty is its diverse collection of Chinese furniture. Some of its most notable treasures include a rectangular white marble table dated to the Qing dynasty, used only once a year, when the Emperor would sit and have tea with his mother on the day of his birthday. It’s specific significance was only discovered when Feuerle approached the Palace Museum in Beijing in the hopes of getting more information on the piece, only to shock the researchers of the museum, who, up until that moment, believed that the table was completely lost to time. Further research also uncovered that a lacquer chair from the same period had come from the emperor’s bedroom. In contrast to the gravitas of royal furnishings, a daguerreotype print of a simple mattress, shabby and worn in, hung above the marble table.

Further on, a lacquered red lute table from the 16th century is on display, also designed to be used by the emperor, Feuerle believes that the piece was executed with a lot of empathy in mind. To him, the idea to present someone as highly regarded as the ruler of the kingdom behind a lute like any regular individual is a staggering thought. Above the table hangs another photo print, this time a closeup of a fig, cut open and facing the camera.

The suggestive nature of the photos on display are no coincidence. For Feuerle, there is a latent erotic element to all of the Chinese furniture he possesses, which he tries to accentuate with the photographs. Some instances are more subtle, such as the placement of a photogram of smoke forms by Adam Fuss in between two Ming dynasty bookshelves; others are completely explicit in their eroticism, such as another of Araki’s works, this time a portrait of a naked woman tied and strung up by rope in front of a stone bench.

Spaces for Collaboration

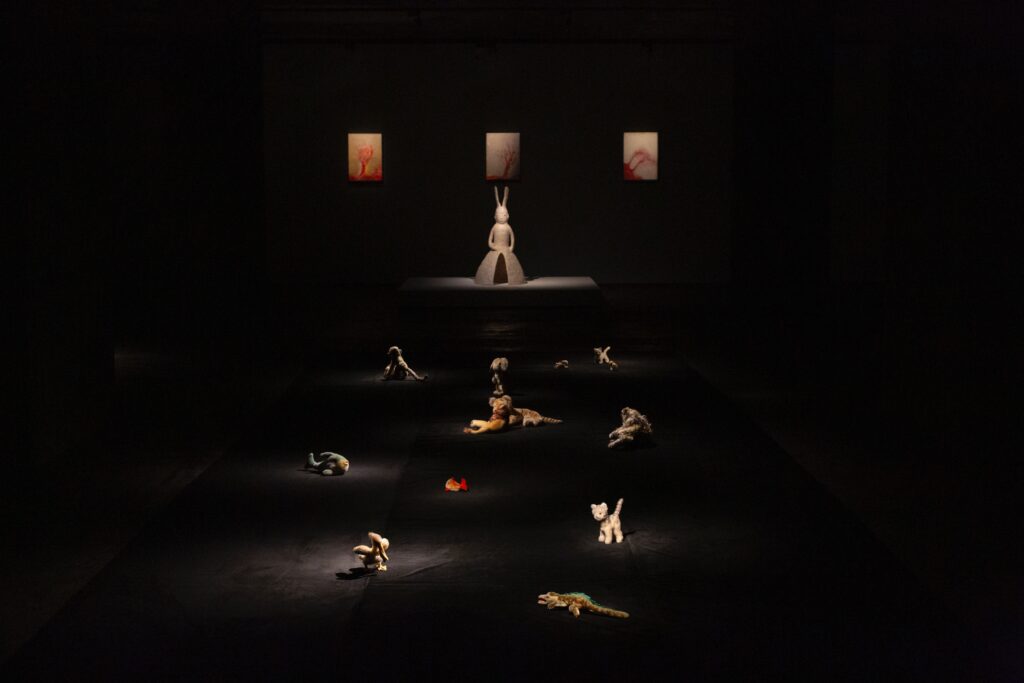

Lastly, there are the works of contemporary art that stand on their own, perhaps the most significant of these is the bronze sculpture commissioned by Feuerle from artist Cristina Iglesias, Pozo XII, which takes the form of a basin or valley with complex roots as if from trees or sinew from a body unseen, depending on how you look at it, and running water that works it way through the middle of the piece in a stream, yet it is not quite a fountain. It was well paired with the nearby sculpture by Zeng Fangzhi, which seemed to be the branches of a dead tree working their way upwards, yet with an oddly anthropomorphic shape, easily mistaken for a human form.

The Collection occasionally opens itself up for contemporary artists to display or perform their works in temporary exhibits in what is called the Silk Room, named for the pitch black curtains which separate the room from the other halls. Reportedly, Feuerle had the curtains made all the way in Thailand to get them in that color, from Jim Thompson, a company named after a man that was known to have revitalized the entire Thai silk industry. What’s more, it was a very special order, as even they had never done curtains that way before.

Spaces for Reflection

Beyond the main exhibition halls of the Feuerle Collection, there is still more to discover. The so-called “Lake Room” is a small space separated from the main hall by panes of glass, containing a small body of water that was there even prior to the renovations. Struck by what he called the “elemental feeling” of the water’s presence in the space, Feuerle opted to forego removing the water outright, instead, the space was cleaned and a geothermal heat pump was installed which now regulates the temperature within the gallery while visitors can witness the still waters reflect the space around them.

In another part of the space, visitors can do some reflecting of their own. The “Sound Room” is just that, a section with a large hanging gong used produce sounds for meditation and contemplation. Every first Saturday of the month there is a gong bath, in which visitors are invited to sit and listen to the subtle vibrations of the gong while on Thursdays, the space holds a meditation session for an hour. If that wasn’t enough, the museum maintains a rooftop garden which it opens to the public certain nights out of the year to screen films or hold talks and parties.

An Ancient Ceremony Reawakened, by Appointment

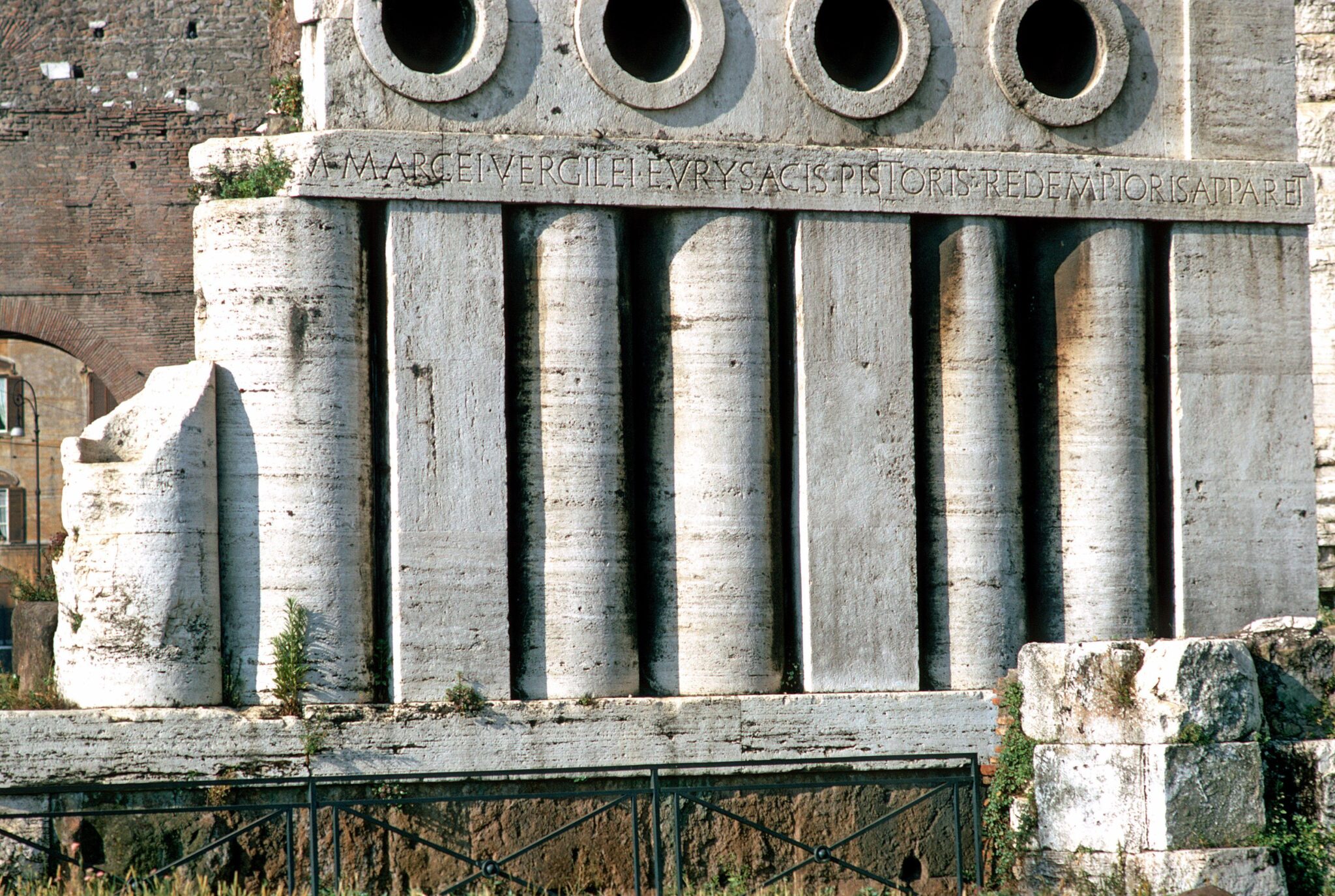

Adjacent to the Lake Room, there is still one more element of the musem left unmentioned, and it is certainly a crucial aspect of Feuerle’s gesamtkunstwerk – the Incense Room. The Feuerle Collection is the first art institution in the world to have created a dedicated space to perform the ancient Chinese incense ceremony, a tradition that dates back almost two thousand years to the Han Dynasty in the 3rd Century AD, with the ceremony as it can be experienced today developed sometime between the 10th and 13th centuries. By appointment, a group of up two four people (who have €600 each) may attend the incense ceremony performed by a trained master.

This ceremony was developed by Feuerle and John Pawson in tandem with Wang Chun-Chin, whom the Collection’s website describes as “the most important scholar and master of the traditional Imperial Chinese incense ceremony”, as well as advisor to Chinese art Jerry J.I. Chen and the furniture workshop Degoo-Chunzai (for whom the latter served as chief designer); thoroughly designed and re-envisioned as a modern equivalent to its ancient predecessor, while still serving as a living document of one of the pillars of Chinese scholarly tradition, the ceremony is intended to provide a “meditative and spiritual” element to the museum, per Feuerle, who himself has been invited to several incense ceremonies in China and Taiwan, and hoped to bring a particular vision of this experience to Europe.

Ancient Ritual Meets Modern Innovation

Rigorously researched and even more meticulously performed, no single element is left unattended. Guests are outfitted with specially designed robes and slippers for the ceremony before they sit at one of the five chairs in the room. In the middle of the room, the specialty table on which the incense is burned is the work of none other than Pawson (the design process alone took him over a year to complete), based on previous designs of furniture found in former ceremony sites in China using African Blackwood, hand-chosen from two tons shipped directly to the workshop (which constructed the table over a further nine month period).

The table features a recess in the middle wherein a bowl with very thinly-sliced incense splinters are placed and lit, but only after they are cut on-site with a special knife (the incense master is required to have practiced cutting with this knife for at least 300 hours before being allowed to perform the ritual). Traditionally, it would take several hours for the wood to be heated in order to produce the oils for the incense, so an electronically-heated surface was installed in the center recess to speed up the process. Naturally, the incense pieces used in the ritual are not the average scents found in your local head shop, they are exceedingly rare wood-based incense such as Green Qinan, Bhutan Qinan, and Hainan Agarwood. Like many aspects of the traditional Chinese scholar’s life, the ceremony’s intended purpose is to elevate the senses and use them to explore one’s own body and spirit as well as to contemplate nature as a whole.

Each Millimeter Counts

Désiré Feuerle’s fastidiousness is well-known and indelible aspect of his approach towards curation, a process where no detail goes unconsidered, this even extended to his choice of air conditioning systems, admitting that he tested no less than a dozen candidates before settling on one system he felt created the most pleasing sound. Similarly, Feuerle personally attended to the placement and positioning of each light source in the collection, adjusting for each individual item on display, sometimes requesting the most minute of changes. “Each millimeter counts” says Feuerle in one article.

Sometimes, his precision is met with coincidence in unexpectedly harmonious ways. The Cage composition that opens the visitor experience, for example, is itself rooted in chance, part of a series of piano works composed by tossing coins in accordance with the I Ching, the ancient Chinese text of divination, an unintentional echo of Feuerle’s own reverence for Asian philosophy and aesthetics. This detail was only discovered after the piece had already been incorporated into the experience, Feuerle chose to leave it, embracing the unintended alignment with his curatorial vision.

Born to Collect

A lifelong aesthete, Feuerle was born in Stuttgart to a doctor who passionately collected everything from ancient Egyptian antiquities to modern pieces by Pablo Picasso and Otto Dix. His father having imparted his love of collecting on him early on, it led him to begin his own collecting journey at the age of eight, starting with antique keys and later expanding to silver teapots, postcards, and eventually historical art objects. His early interest in the form and symbolism of objects, such as ancient Chinese terracotta toys and Baroque European jugs, revealed a fascination with the relationship between function and aesthetic.

As a teenager, he bought his first Khmer sculpture, a small goddess head, which now forms part of his Berlin-based Feuerle Collection. He studied art history in London and New York, took Sotheby’s fine art course, and began his career at Sotheby’s, where he visited private collectors like Ronald Lauder and quickly absorbed a key principle: true collecting is about quality, not quantity. On weekends, he would make a ritual out of going to the Met or the MoMA, study a single artwork in silence, then walk through Central Park to reflect, his own form of self-education. In particular, a Khmer sculpture he first saw at 17 remained vivid in his mind, deepening his interest specifically in Khmer art but more broadly in art that transcends time and place.

By 1990, after working for Michael Werner in Cologne and appraising works by Baselitz and Polke, Feuerle launched his own gallery. His shows broke with tradition, juxtaposing Yves Klein and Joseph Beuys with Gothic Madonnas, or placing sculptures by Basque artist Eduardo Chillida alongside ancient Chinese terracotta sculpture, only to later discover that the latter artist was aware of the very same sculptures when creating his work (as with the Cage pieces, this was one of many chance synchronicities in Feuerle’s career). He was driven by a need to create unexpected relationships between objects, to collapse the distance between centuries and cultures. “As a collector you have to take all sorts of risks, you have to be adventurous,” he said, an ethos he lived fully, once even attempting to reach an ailing Francis Bacon at his home in search of a collaboration during his twilight years.

A Lifelong Connection to Asia

Since having first visited China as a teenager in the late 1970s and noticing a similarly curious spirit in the people he met, he remains deeply influenced by Asia. He now spends half the year in Asia, primarily based in Bangkok with occasional travels through China, Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Myanmar, while his family is based in Barcelona.

The Feuerle Collection was co-founded with his wife Sara Puig, a member of the Puig fashion and perfume family and current president of the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona. A frequent lecturer and board member of institutions such as the Tate Foundation, Cleveland Museum of Art, and Museo del Prado, Feuerle remains committed to curating inter-cultural, atemporal encounters that encourage intimate, contemplative experiences of art. Although he no longer collects keys and jugs as he did in his youth, Feuerle admits he still pours water from a baroque 18th-century Augsburg jug during special occasions.

Why Berlin?

With a lifestyle that spans such a broad geographical range, many wonder why Feuerle chose Berlin of all places to host his collection. Initially, Berlin didn’t even cross his mind. Having considered places as disparate as a remote Spanish monastery in the mountains, old Italian palazzi in Venice, a room in New York’s Metropolitan Museum, as well as locations in London and Istanbul, Feuerle eventually realized that Berlin’s well-known openness to new forms of self-expression as well as its reputation as a youthful city serves as the perfect ground for his explorations into curating art in new and unorthodox ways.

Feuerle took a risk, and it appears to have paid off. With around 10,000 visitors annually, more than half of them local, and an average age of just 23, the collection is steadily embedding itself into the cultural fabric of the city. As Feuerle puts it, “Many of our visitors are very emotionally touched. It has had an impact on them. It is an experience, which gives them good energy, and many of our visitors talk about this like they would have gone through a gate, which calms them down, creating an inner peace.”

An Institution for Contemplative Art

Beyond the permanent exhibits and ceremonies, the Feuerle collection hopes to keep the momentum going, over the years having opened its doors for temporary exhibits by artists such as Japanese conceptual artist Leiko Ikemura and English ceramicist Edmund de Waal, as well as participating in city-wide events such as the Berlin International Film Festival and the Berlin Biennale, during which the space holds screenings, panel talks, dinners, and more. Other events included a traditional shakuhachi concert by Reison Kuroda, as well as a joint tea ceremony, dance performance, film screening by Po-nien Wang, Wai Kung, and Lin Wang, a syncretic experience inspired by The Mountain Spirit, a poem from the Nine Songs by Qu Yuan, an ancient Chinese poet from the 4th and 3rd centuries BC.

By placing his collection in an underground bunker, Feuerle may appear to be shielding it from a hostile world, as if art itself were under siege. Yet the effect is the opposite: rather than a fortress, the space becomes a refuge for focus and reflection. Here, far from the noise of the outside world, the only real threat is distraction, and the only demand is to surrender to the art and truly see it on its own terms.

The Feuerle Collection is located at Hallesches Ufer 70, 10963 Berlin, and is currently open by appointment only from Friday to Sunday, between 2 to 6 PM.