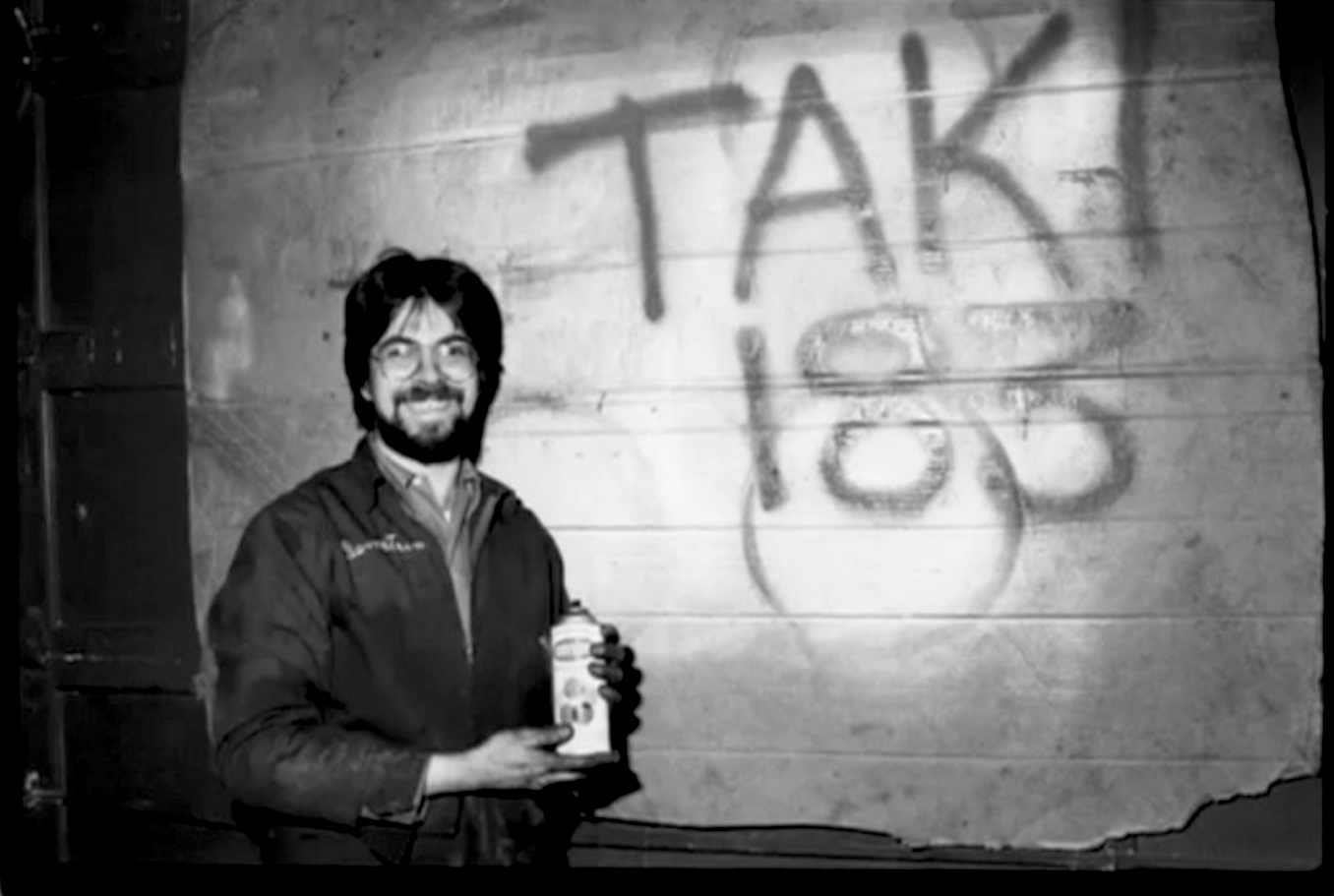

Graffiti, the most enduring form of spontaneous creativity in the urban landscape has surprisingly simple stylistic origins, and while the real names and faces behind much of early graffiti remains unknown, TAKI 183 is one New York artist that famously made waves in the 70s and is still writing his name on walls today, over 50 years later.

The history of people writing their names on walls is nothing new, and seems to go back as far as we’ve had walls, but the story of graffiti as a modern phenomenon has some clear origin points, one of the most interesting names from the earliest days of graffiti, before pieces, and before throw ups, is a writer by the name of TAKI 183. Though the name might seem cryptic to the uninitiated, its appearance in blocky scrawl across subway cars, mailboxes, and storefronts in the early 1970s marked the beginning of modern graffiti culture, not only in New York City but around the world. Behind that name was Demetrios, a Greek-American teenager from Washington Heights, whose casual act of self-expression would ignite a global movement, and he was only 15 years old when he started.

From Washington Heights to Citywide Infamy

TAKI 183 (short for Dimitraki, a diminutive of his given name, and 183rd Street, where he lived) wasn’t looking to become a cultural figure. Like many teens in his mostly Greek-American neighborhood in Washington Heights, he was drawn into tagging through local peers, particularly those inspired by another early graffiti pioneer, Julio 204. As was common for the time, Julio had also taken his name and street number as a tag, but stopped writing after being caught. TAKI, however, saw the format, took it, and ran with it. As a foot delivery boy for luxury cosmetic products, he moved throughout all five boroughs, giving him the perfect canvas: the city itself.

Beginning in the summer of 1969, TAKI began tagging ice cream trucks in his neighborhood before expanding to subway cars, construction sites, and building walls. He even tagged the door of a Secret Service car, an act that nearly got him into serious trouble but cemented his reputation as fearless and omnipresent. His tags weren’t elaborate or stylized. They were simple: bold block letters and numerals written under the cover of his delivery box held over the surface to prevent the odd witness, each tag done quickly and with the kind of quiet authority that comes from repetition. And that was the point. He wasn’t trying to create art, he was trying to be seen, and go all city before going all city was a thing.

“TAKI 183 Spawns Pen Pals”: The Article That Changed Everything

In July 1971, a journalist for the New York Times caught notice of TAKI writing one of his infamous tags, and, after having followed him home, interviewed him at his door, after which he published a short but pivotal article titled “‘Taki 183’ Spawns Pen Pals”, and with it, graffiti broke into public consciousness. The article wasn’t focused on vandalism per se, it was more fascinated by how a name could proliferate across a city without any formal medium. Suddenly, people wanted to know: Who was TAKI 183? Why was he writing his name everywhere?

The article turned TAKI into an underground celebrity. Unlike gang tags or territorial graffiti that had existed before, TAKI’s work wasn’t tied to a group. It was personal. This shift from group identity to individual expression is what set TAKI apart. He wasn’t marking turf; he was marking existence.

The Blueprint for Graffiti Culture

What TAKI 183 started soon evolved into the foundations of a culture. At first, other kids in his neighborhood found respect for him, and got in on the act themselves. Soon enough, thousands of young writers, many from underserved or marginalized communities, saw a way to make their presence felt in a city that often overlooked them, without joining a gang to do so. The practice of including a name or alias plus a number indicating a street or neighborhood became a standardized format. From Tracy 168 to Stay High 149, the format spread like wildfire. The city’s subway system became a gallery of sorts, displaying these rolling canvases to millions of people each day.

By the 80s, full-color murals and elaborate “pieces” (short for masterpieces) had evolved out of this early tagging, but TAKI’s DNA was still visible in every signature. Despite this, TAKI himself faded from the scene not long after his rise. He wasn’t arrested or forced out. He simply stopped. According to him, he never thought of what he was doing as art or even that interesting, it was a pastime that had run its course. In his own words, “he was done with graffiti and had moved on to being a sensible grown-up. He went to college and learned car repair and bodywork. He raised a family.”

Resurfacing in the Modern Era

For decades, TAKI 183 disappeared from public life. He worked quietly, running an auto repair shop in Yonkers, far removed from the subways and streets that had once borne his name. But in 2016, he re-emerged as one of the featured figures in “Wall Writers: Graffiti in Its Innocence”, a documentary by Roger Gastman, chronicling the birth of the graffiti movement. The film, along with the accompanying book, gave TAKI the platform to tell his story on his own terms.

Since then, TAKI has leaned into his legacy. His website, taki183.net, offers prints and memorabilia. He has collaborated with contemporary street artists, participated in gallery exhibitions, and occasionally returns to the streets. In 2023, he was part of a large graffiti retrospective in downtown Manhattan, and his tag was spotted on curated wall installations in Berlin and Paris.

Interestingly, TAKI never considered himself a street artist, and he still doesn’t. But his place in the cultural canon is secure. Artists from Jean-Michel Basquiat to Banksy have cited the early NYC graffiti writers as crucial to the development of their aesthetic and approach. In the same way Marcel Duchamp turned a urinal into art, TAKI turned a name into a signal, both deeply personal and explosively public.

Legacy: A Cultural Shift in Five Letters and Three Numbers

TAKI 183’s legacy is less about what he wrote than what he represented. He was the first graffiti writer to achieve widespread name recognition, not through artistic flair but through sheer consistency. His work was about presence, not permission. He wasn’t trying to provoke or politicize, though he often compared his tags to the political posters pasted to subway and city walls during election years, seeing what he did as no different. No better, no worse. He was asserting his existence in a city that could easily erase you if you let it.

In doing so, TAKI gave rise to the idea that a city could become a living notebook, and that anyone with a marker or spray can could write themselves into its story.