In the summer of 1981, Japanese photographer Joji Hashiguchi left Tokyo on a self-directed journey through Liverpool, London, Nuremberg, West Berlin, and New York to capture young people on the streets of those cities and show them as they were, the images he captured are a document of the times, yet the struggles they depict are hauntingly timeless.

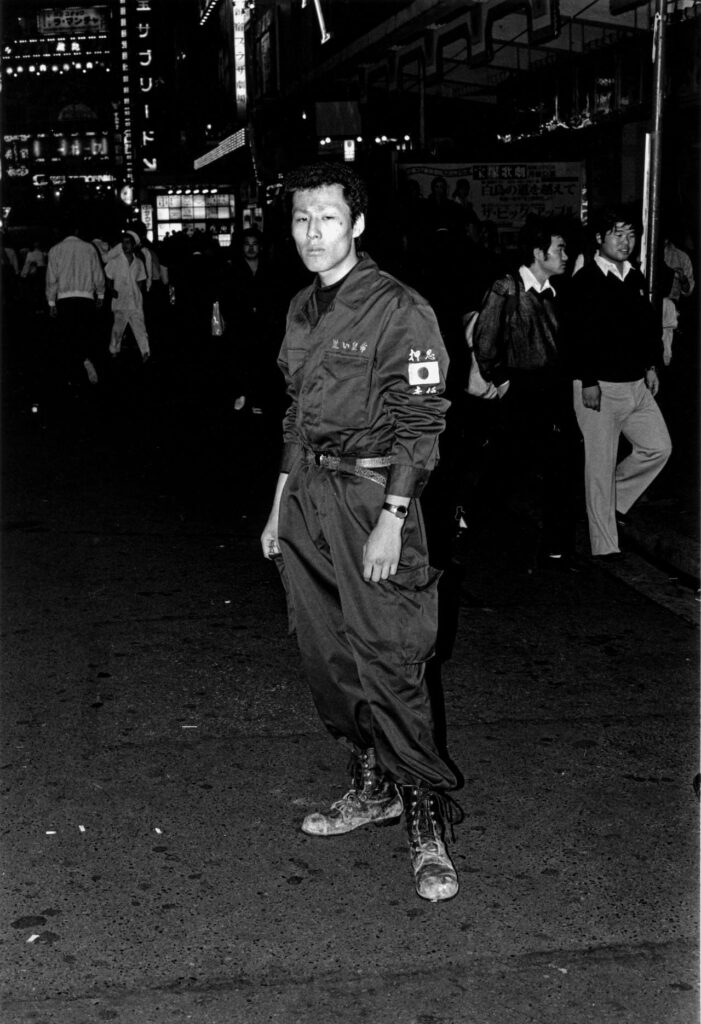

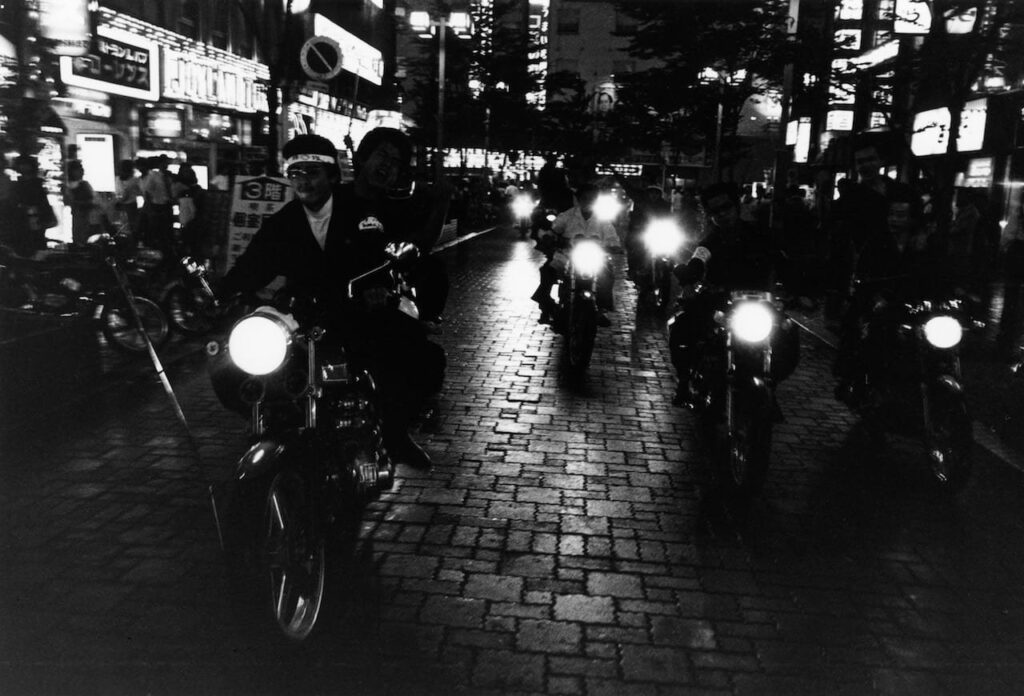

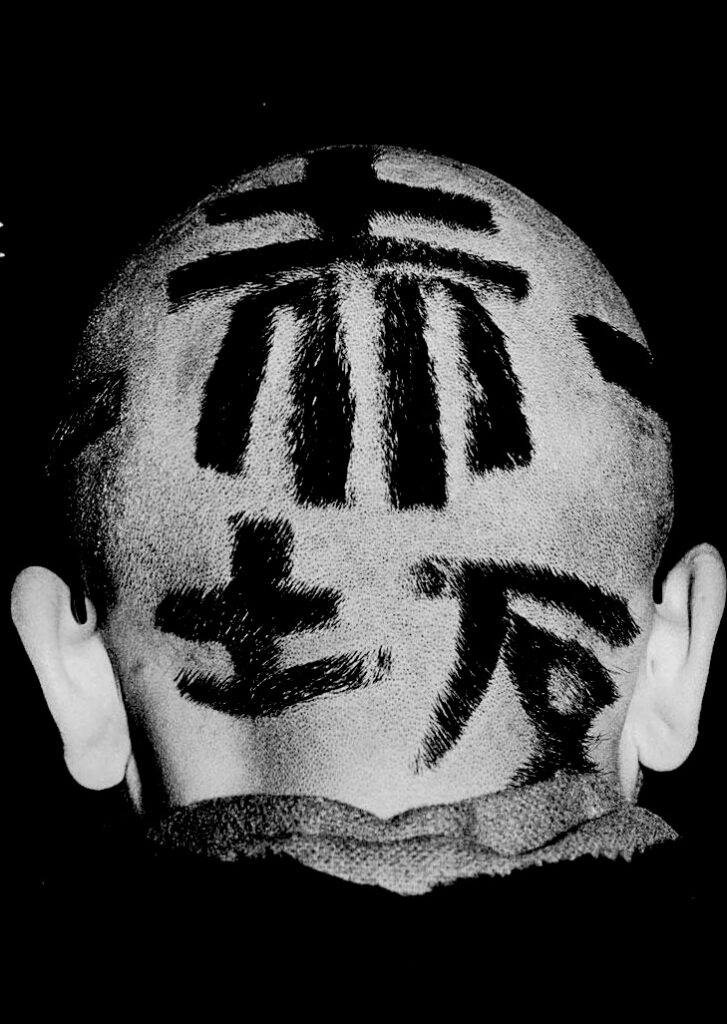

Already a published photographer in his native Japan, the self-taught Joji “George” Hashiguchi was no stranger to directing his lens towards young people who had slipped through the cracks. Having just published Shishen (‘The Look’), a prize-winning book of photographs of the youth counter-cultures in Tokyo seeking to escape the pressures of school and home life in the streets, Hashiguchi wanted to go beyond the borders of his home country.

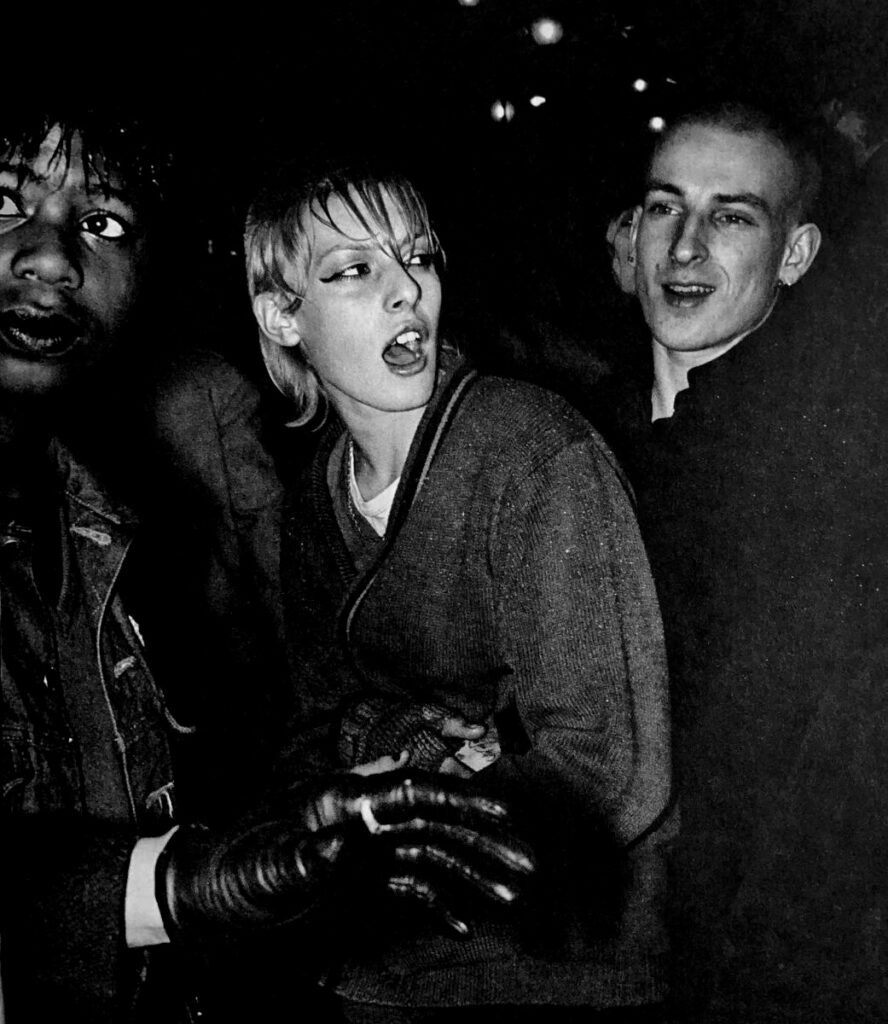

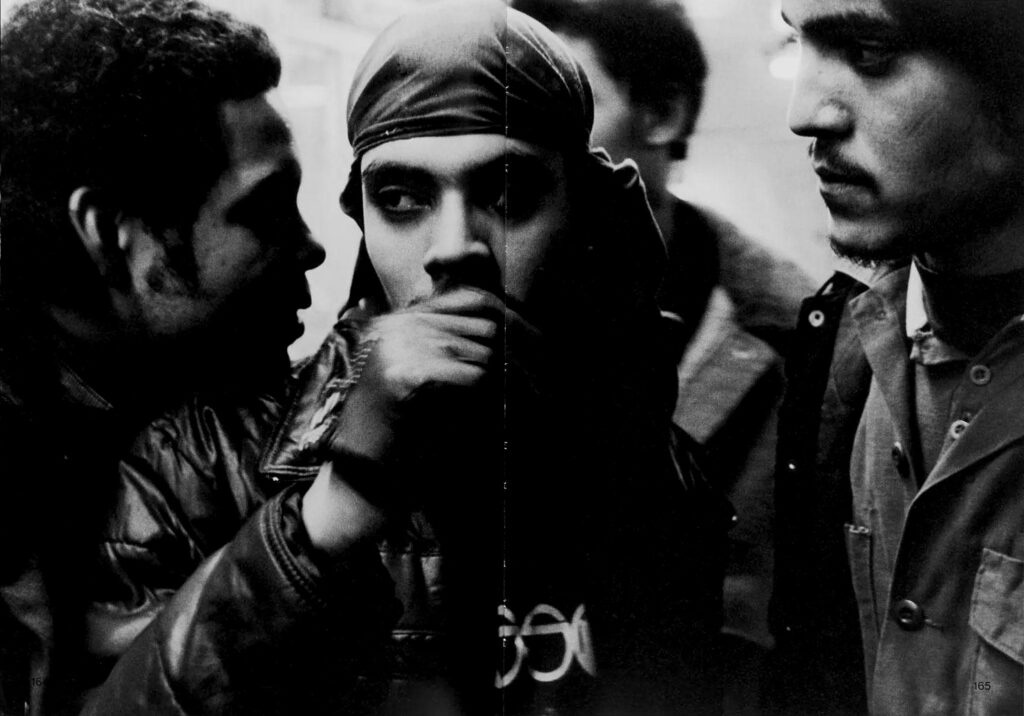

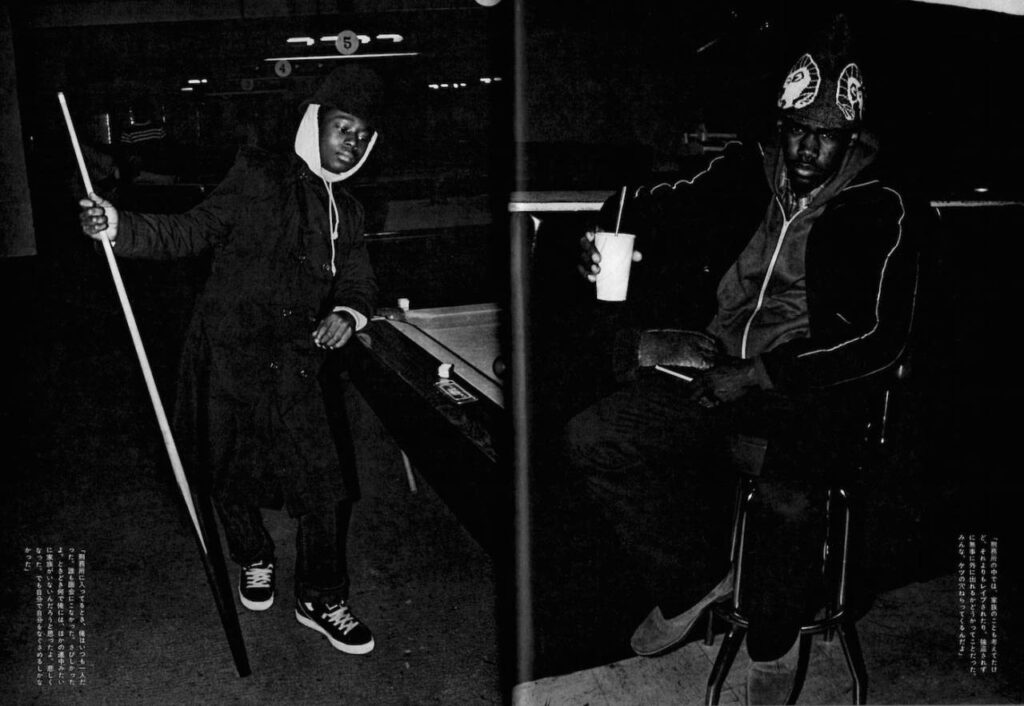

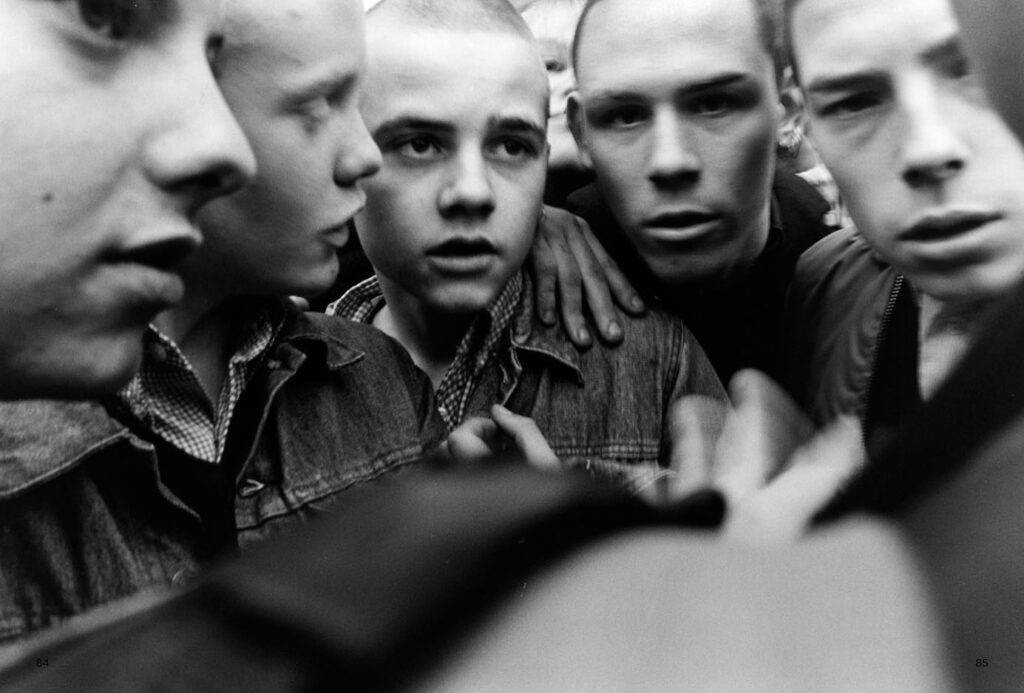

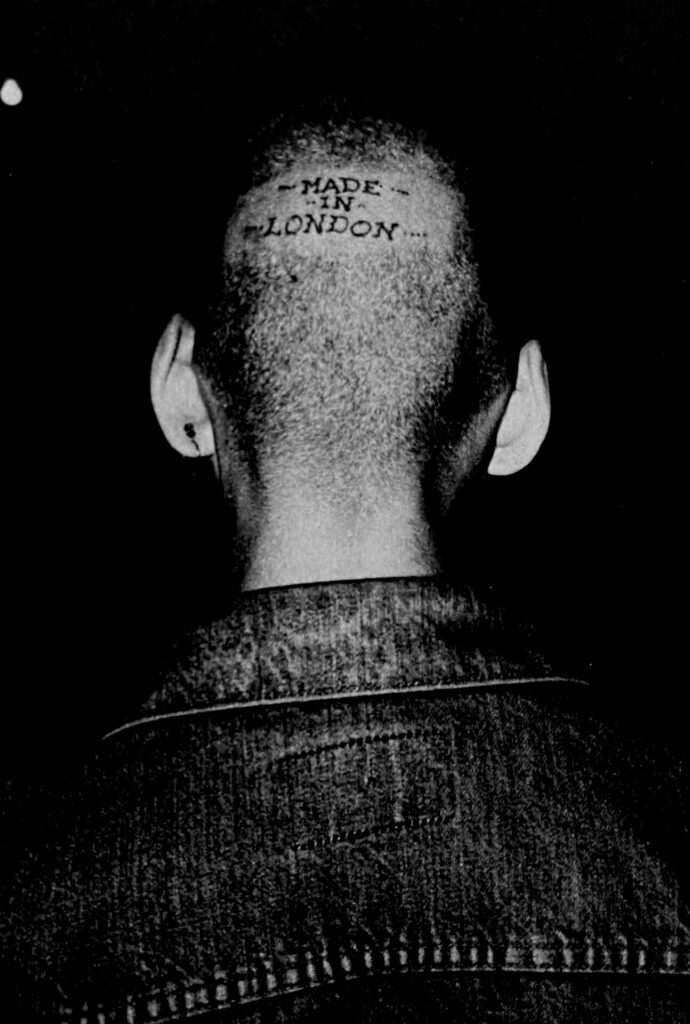

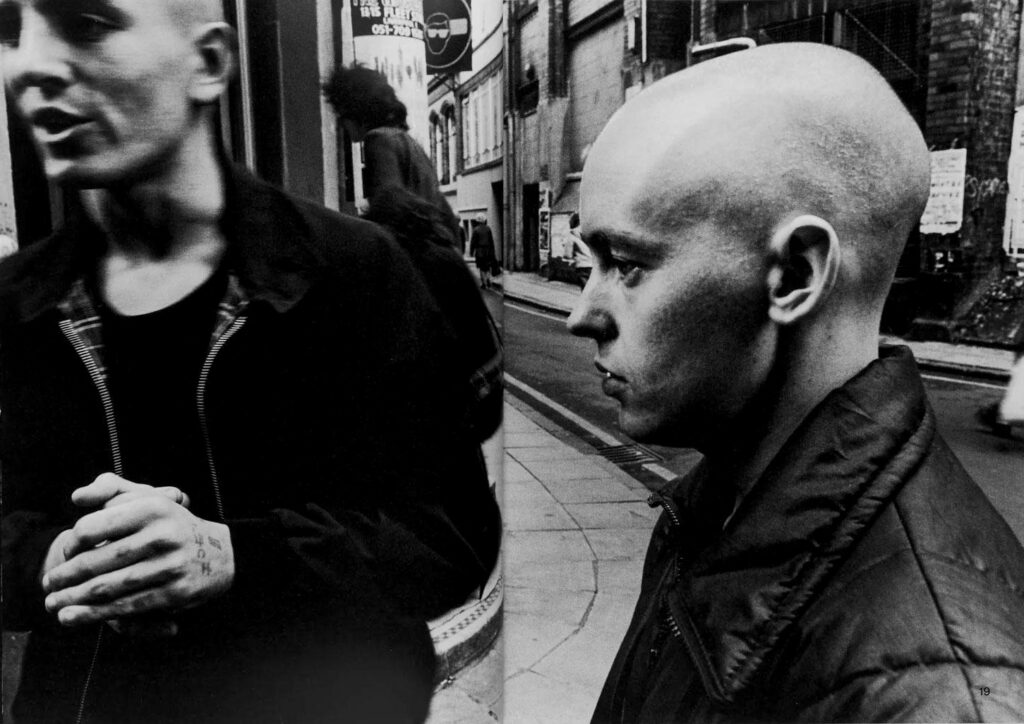

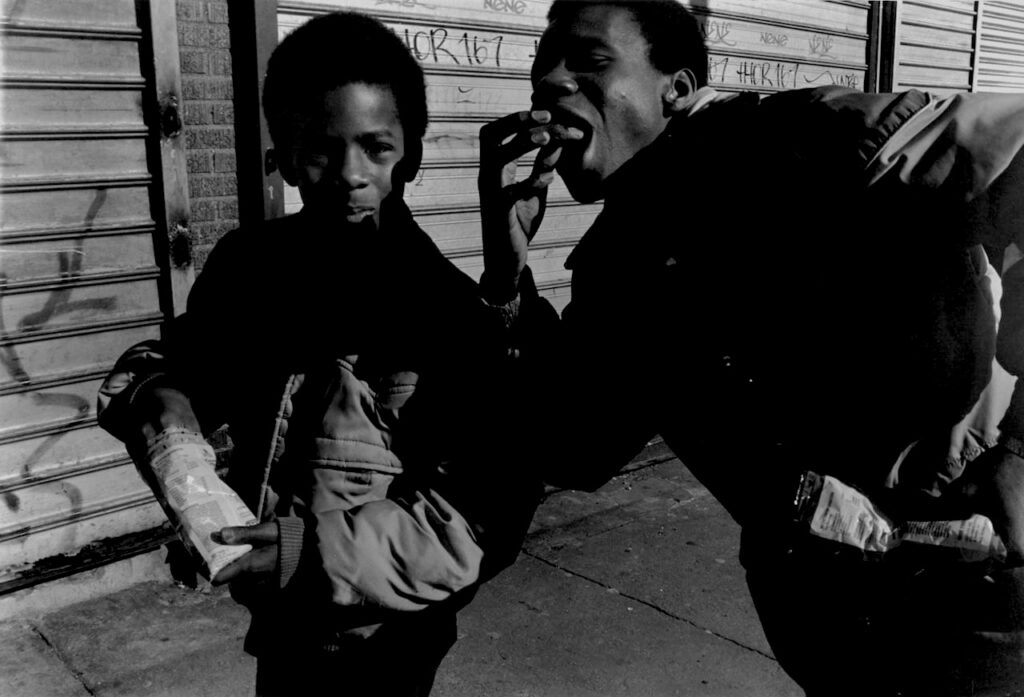

Having read about youth protest movements unfolding across Europe and wanting to document the conditions of the marginalized, the frustrated, and the forgotten wherever he could find them, Hashiguchi set out for a trip abroad. mostly total outsiders and minority groups like heroin addicts in Germany, London’s skinhead groups, students in Tokyo, or impoverished teenagers in New York.

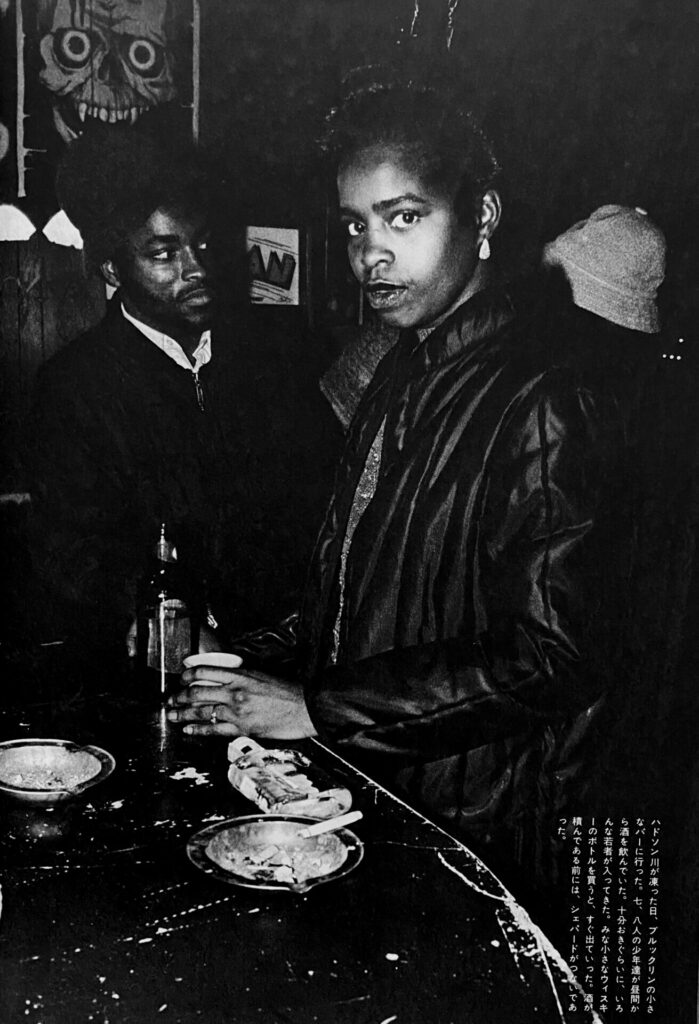

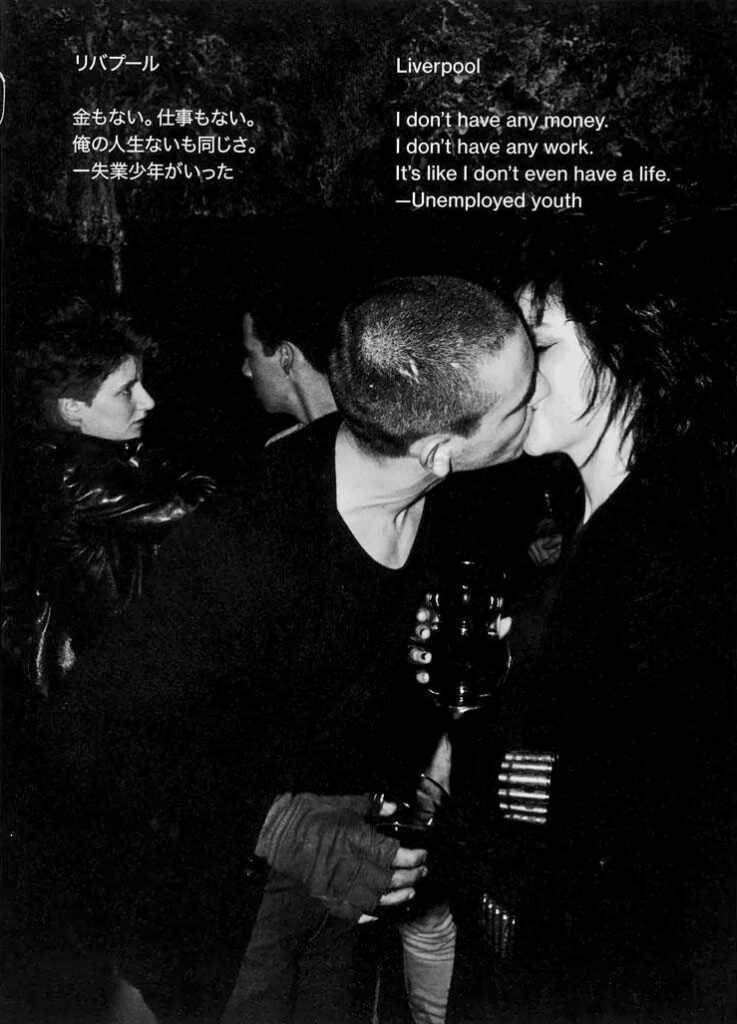

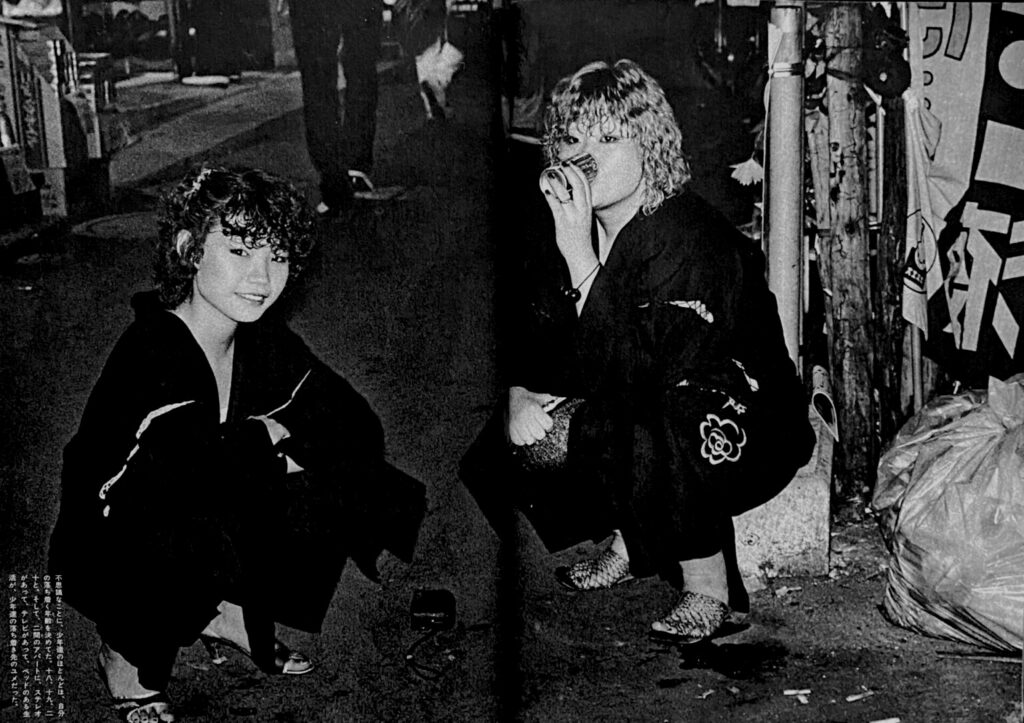

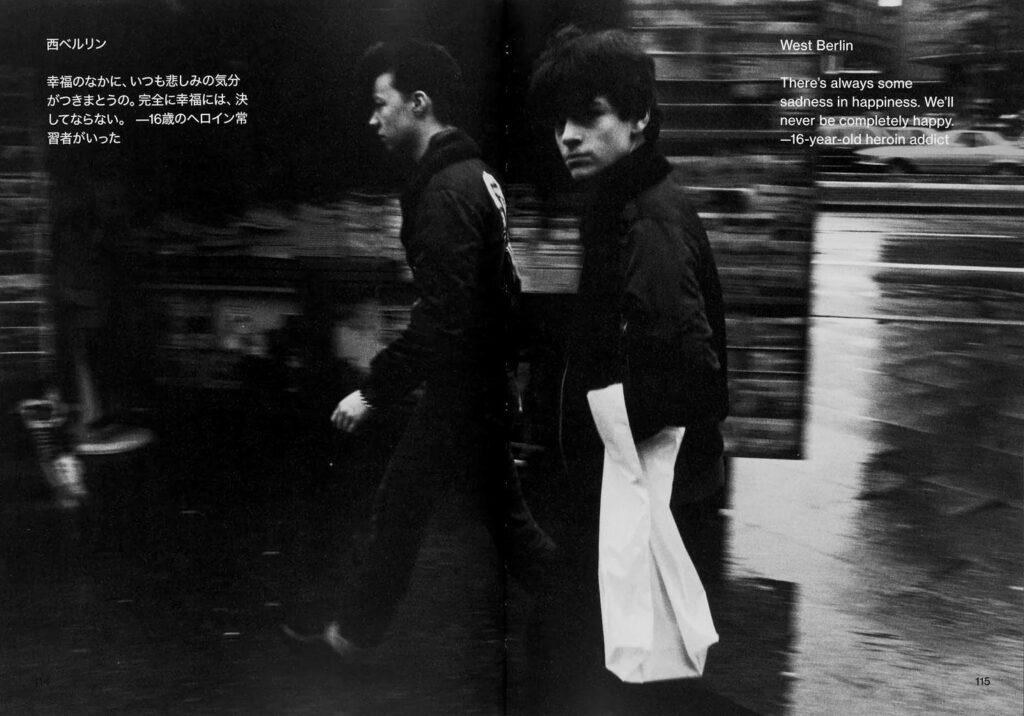

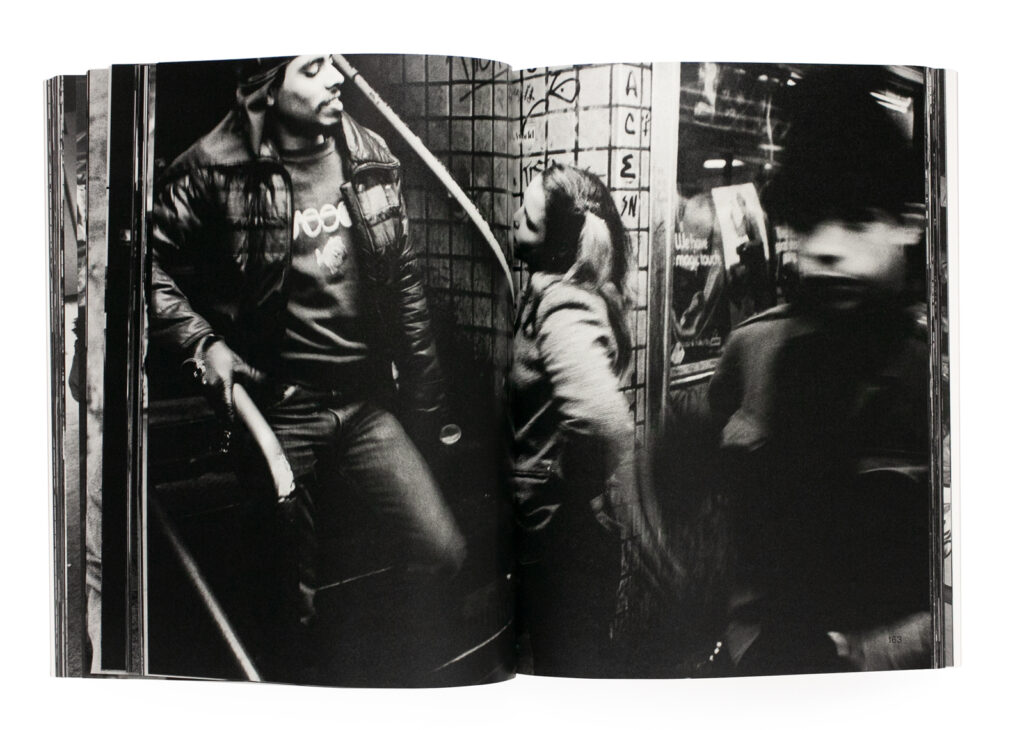

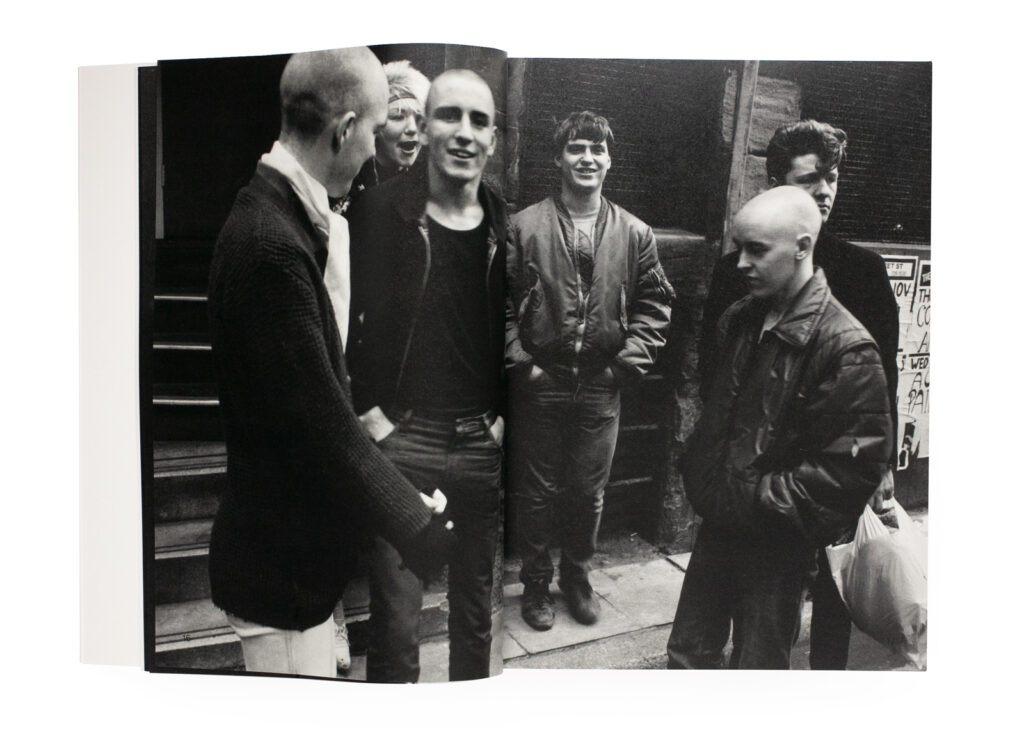

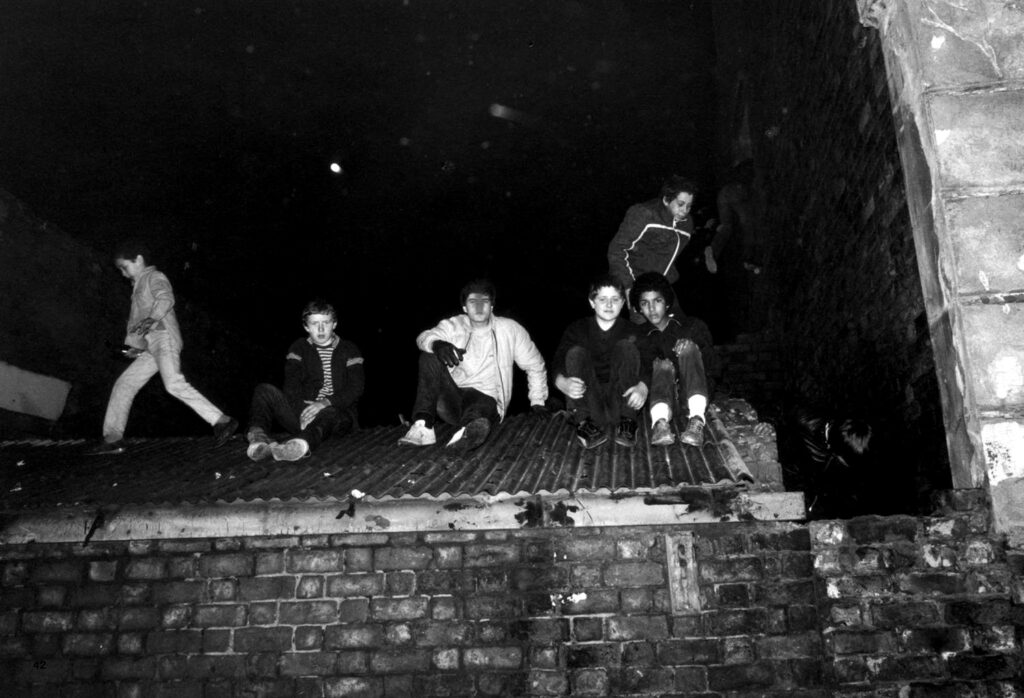

The result was Oretachi Doko ni mo Irarenai: Areru Sekai no Judai (released in English as We Have No Place to Be), published a year later in 1982. The series, shot entirely in black and white using 28mm and 40mm lenses, depicts youth in transit and in stasis: loitering at bus stops, slumped in cafés, sharing smokes in alleys, each frame tethered to a sense of fatigue, uncertainty, or faint fraternity with their peers. Across over 100 photographs taken over two years that he chose for the book, Hashiguchi showed how youth culture, though shaped by local histories, shared a sense of disenfranchisement that spanned the globe.

He approached each place with deliberate care. “I could not take away the pain and anxiety from the youth I photographed,” he later said, “but I could get close to them because I understood their inability to build relationships with mainstream society.” His empathy was not romanticized; he acknowledged that when he pressed the shutter, he felt “as though my soul is coated in iron.” Still, he offered something few others did: to look carefully, without judgement. “Perhaps the youth accepted me because people passed by them every day, either avoiding them or casting a cold glare.”

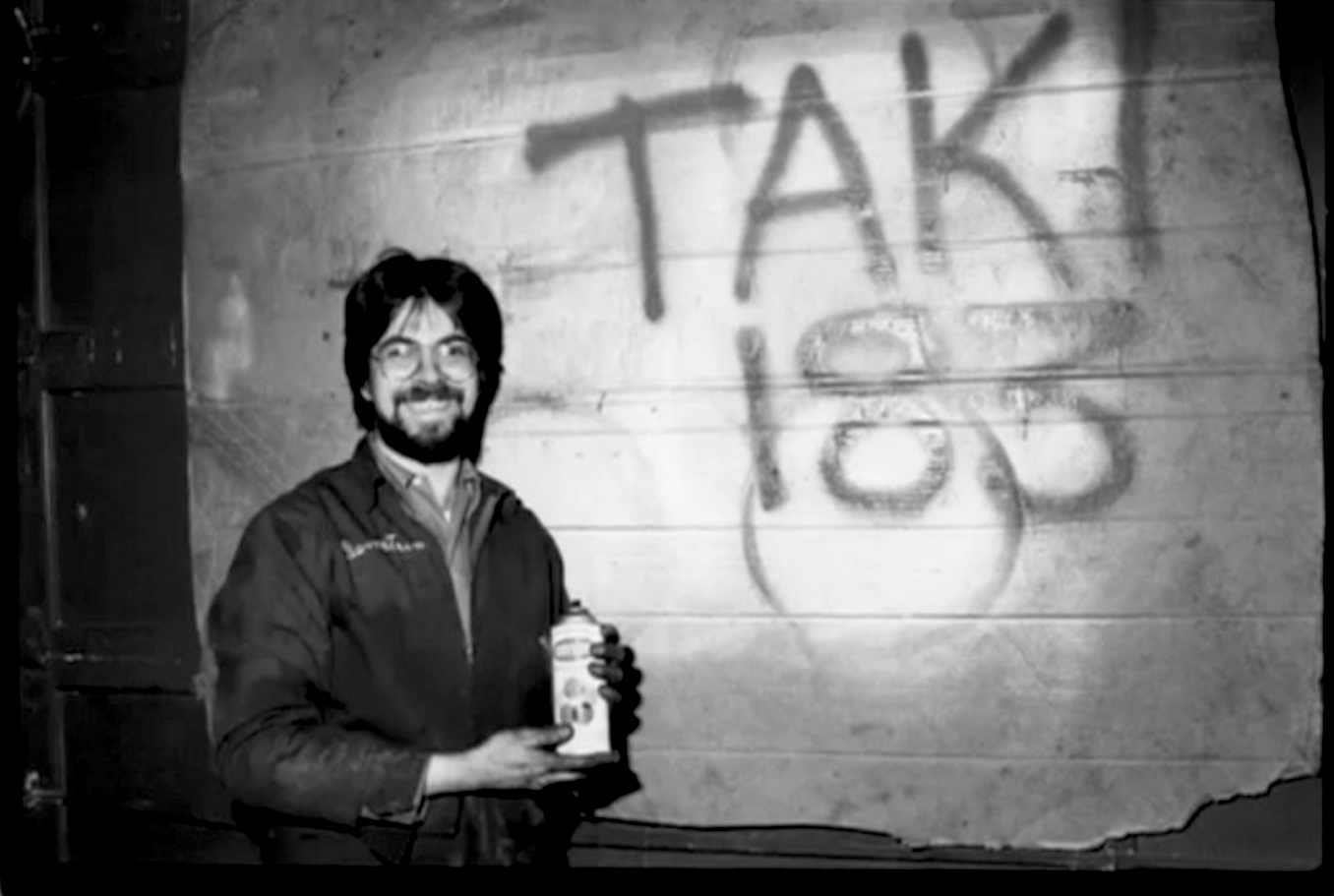

His route was inspired as much by cultural resonance as the political and social unrest that was taking place at the time. “There were a number of reasons why I wanted to go to Liverpool — one of them was to see the place where The Beatles had made their music,” Hashiguchi recalled. “I had also read about the Toxteth riots… images of young men hurling stones on streets engulfed in flames burned in my mind.” In West Berlin, it was Christiane F’s grim autobiography Zoo Station that drew him to the city. Nuremberg offered a contrast: KOMM, a youth-run experimental “school outside of school,” stood as a rare example of cooperative urban reform, while New York was experiencing the tension of the cold war and rapid social change.

Hashiguchi traveled between cities by train and ferry, intentionally avoiding flights. “I wanted to experience the atmosphere of the space in-between; to feel the shift in culture, and to feel the physical distance between each city with my own body,” he said. The act was intentional, he wanted to remain as grounded as possible and see what others were seeing, which often mean witnessing unemployment, poverty, prejudice, drug use, and the lingering effects of violence. The series often presents the viewer portraits of people marred by difficult lives: eyes staring off into the distance, tired faces, bruised bodies, loneliness.

Each chapter in the book, one for each city, begins with a quote told to Hashiguchi by a local youth: “I don’t have any money. I don’t have any work. It’s like I don’t even have a life.” from an individual in Liverpool. “I didn’t have anything to do, I was bored. Back then, the only thing around me was heroin.” from Nuremburg.

We Have No Place to Be was reissued in 2020 by Session Press with around thirty previously unseen photographs as well as Hashiguchi’s Tokyo-based works from Shisen. The edition also includes Mika Kobayashi’s critical essay and a foreword by artist Yoshitomo Nara, reflecting on his own time spent living in Europe during the 80s. Kobayashi notes, “Although each country is undoubtedly home to its own unique social and historical context, these youths shared a common discontent and pent-up frustration that knew no outlet … Unable to choose their place of birth, these youths were conscripted to exist within their predestined location in time and history, all the while mouthing their cry, ‘we have no place to be.’”

Reflecting on the book’s reissue, Hashiguchi remarked: “Although the way we live has changed, I do not believe the human experience has. Youth today are suffering from the same anxieties about their future, and relationships with their family and friends, as we were 40 years ago. In Japan, suicide rates among young people continue to rise year on year. Despite new ways of communicating, these statistics prove that isolation and division within society is deepening.”

Though his photographs are steeped in hardship, they occasionally flicker with moments of intimacy and resilience. “Among all the disorder and violence,” Hashiguchi wrote, “on the street I saw tolerance, and kindness… the street does not choose the people who walk it — it is out of reach of ordered society. The street is the cradle of humanity.”