In 1985, when Richard Avedon’s In the American West debuted, it didn’t just surprise people, it unsettled them. Avedon, the high priest of polished elegance in fashion photography, had done something almost unthinkable: he turned his camera away from the glitz of Paris runways and Manhattan studios, and toward the sunbaked plains, dusty truck stops, and weathered faces of America’s overlooked.

This wasn’t the Avedon the world knew. Born in 1923 in New York City, Avedon became famous for his work with Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, and The New Yorker, capturing the likes of Audrey Hepburn, Marilyn Monroe, and Truman Capote with an almost architectural precision. His portraits were controlled, glamorous, hyper-stylized. But In the American West, a five-year project commissioned by the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, was something entirely different. It was stripped-down, raw, and deeply human.

A Road Trip into the Soul of a Nation

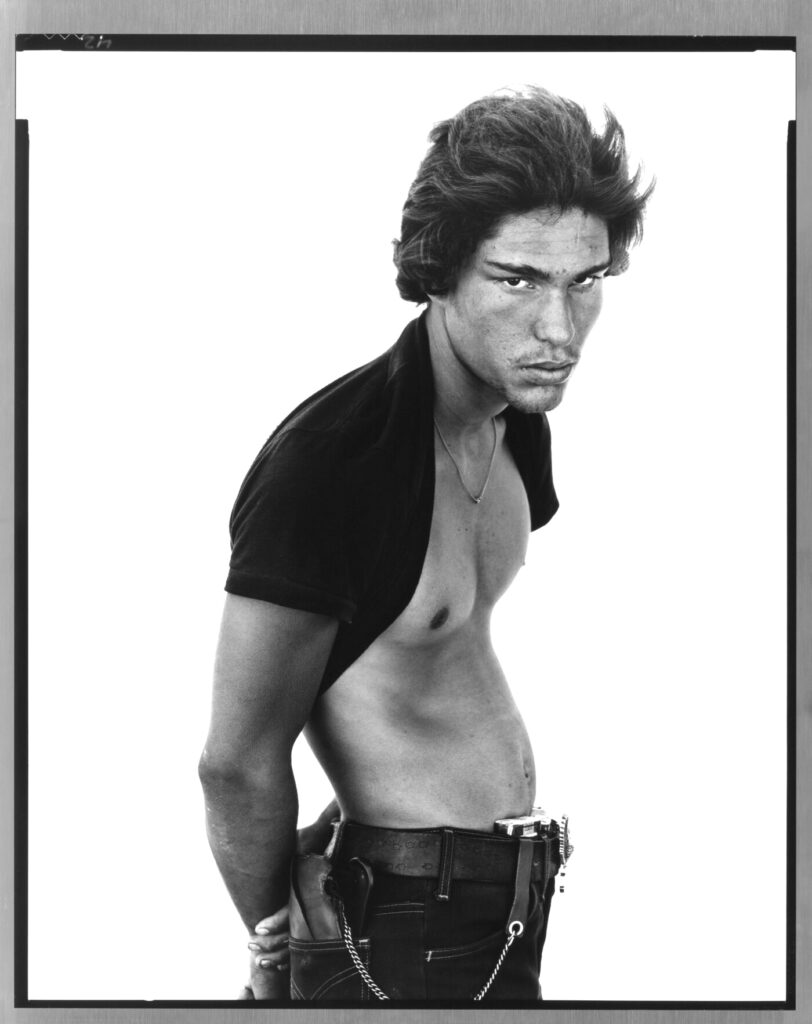

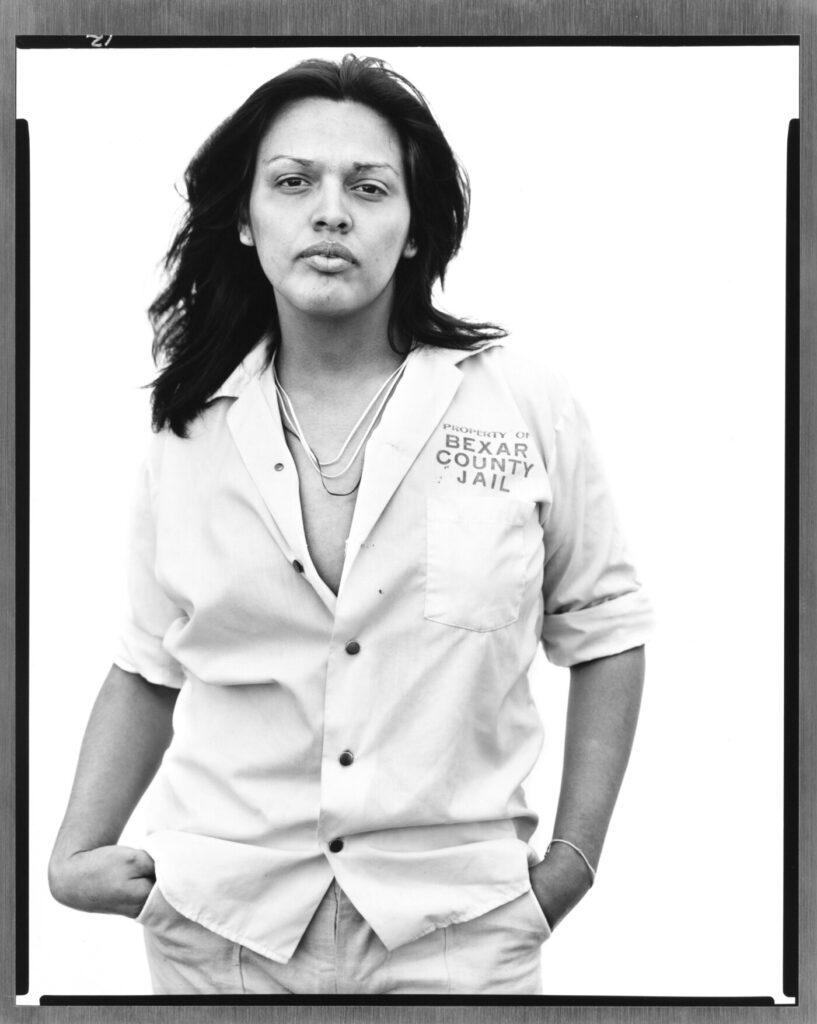

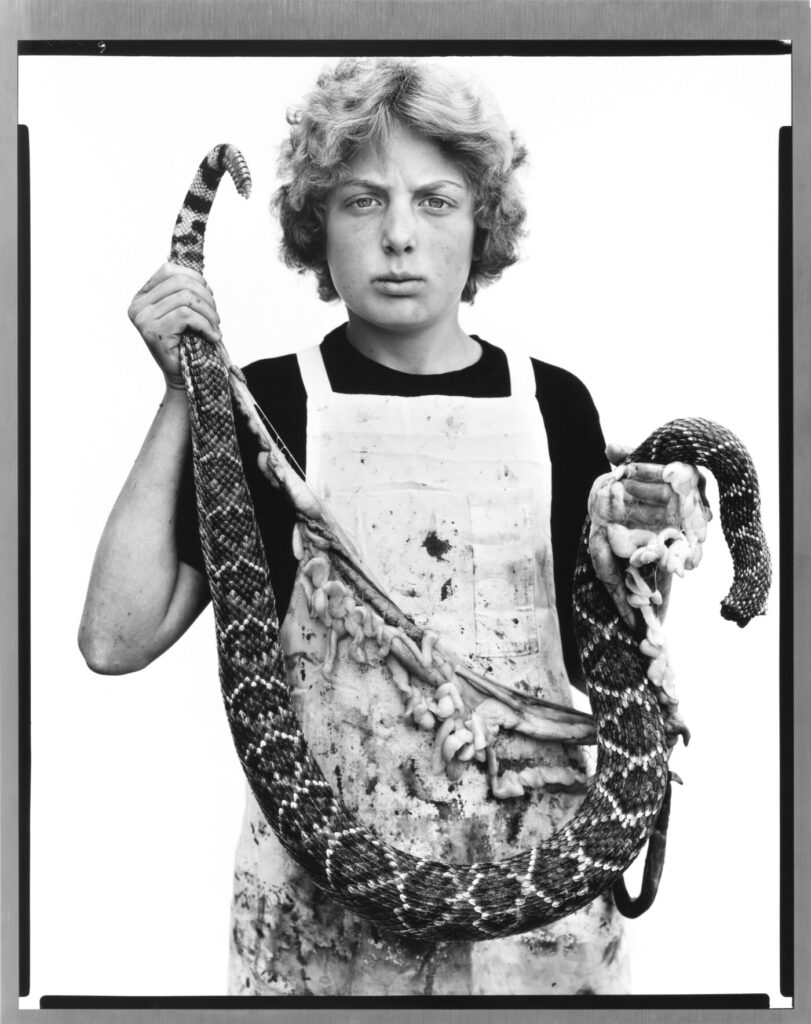

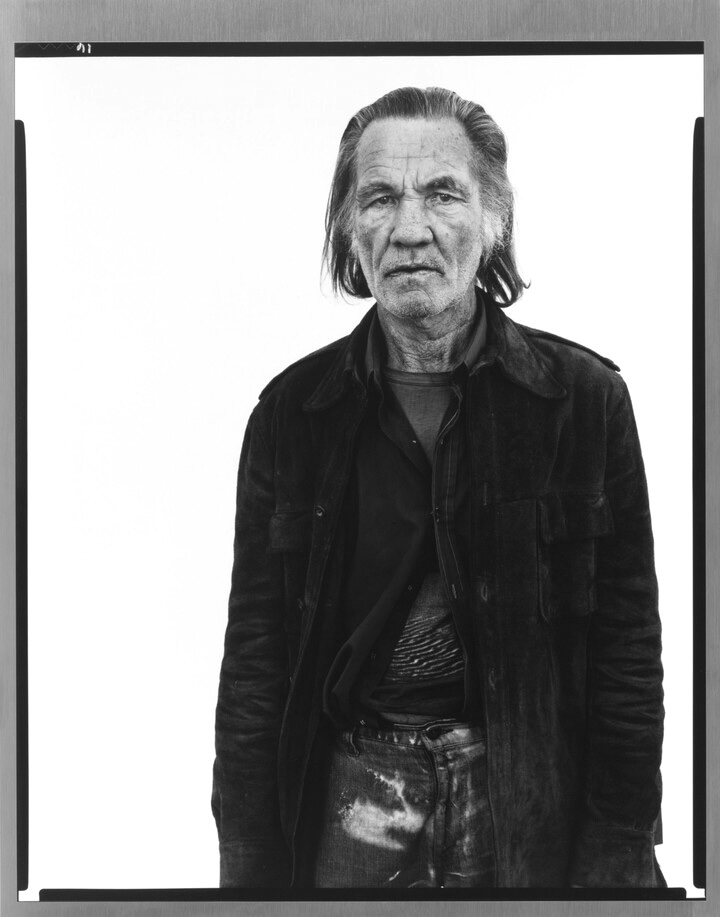

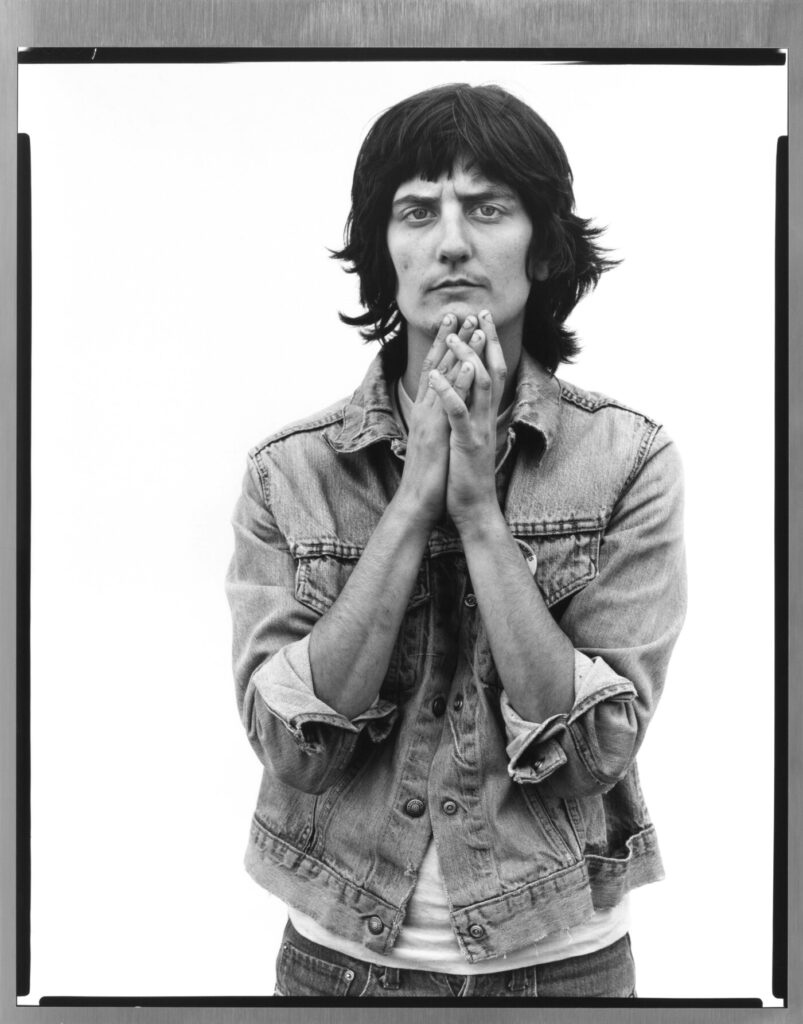

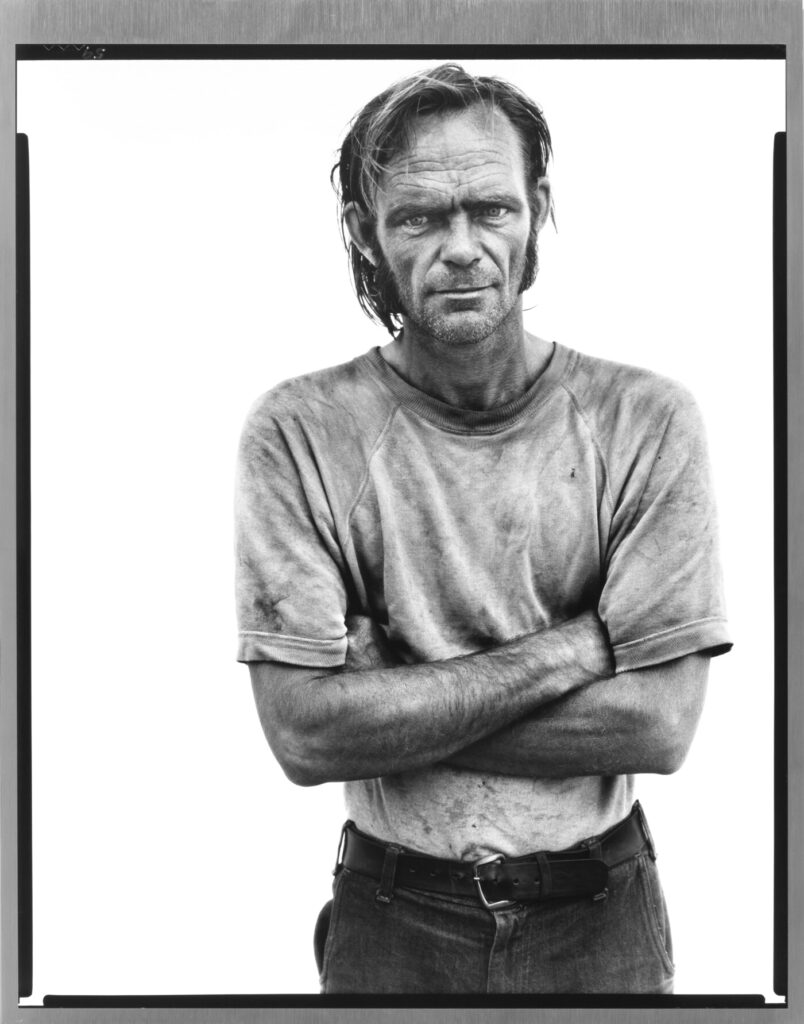

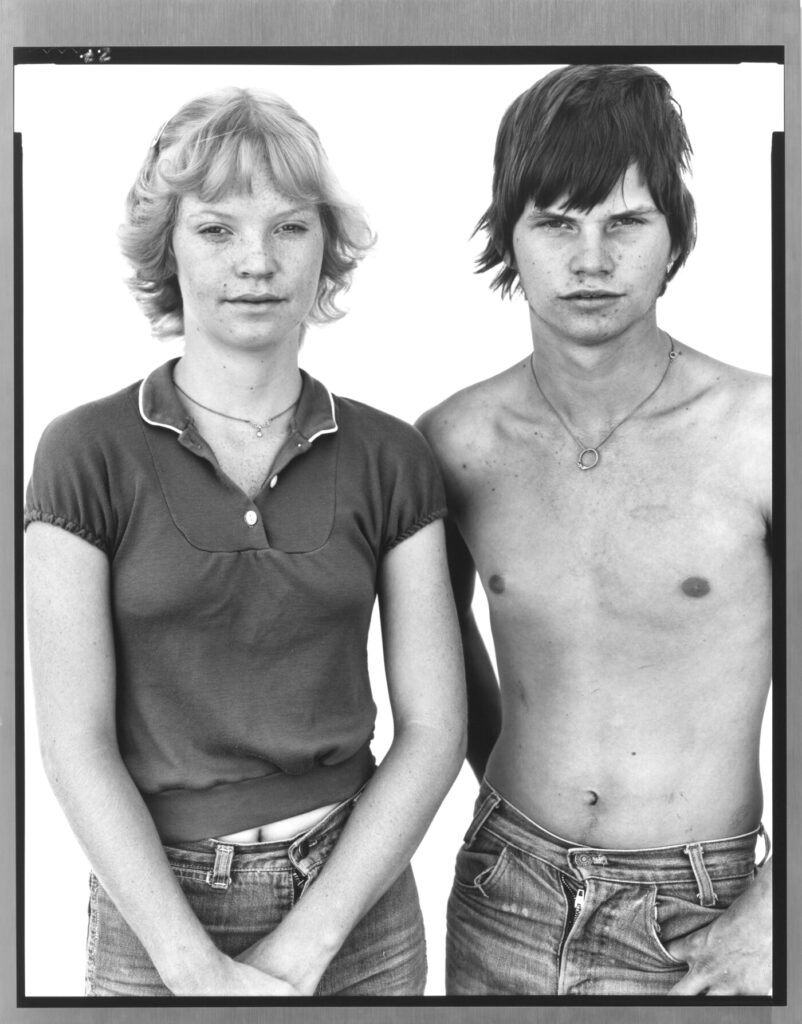

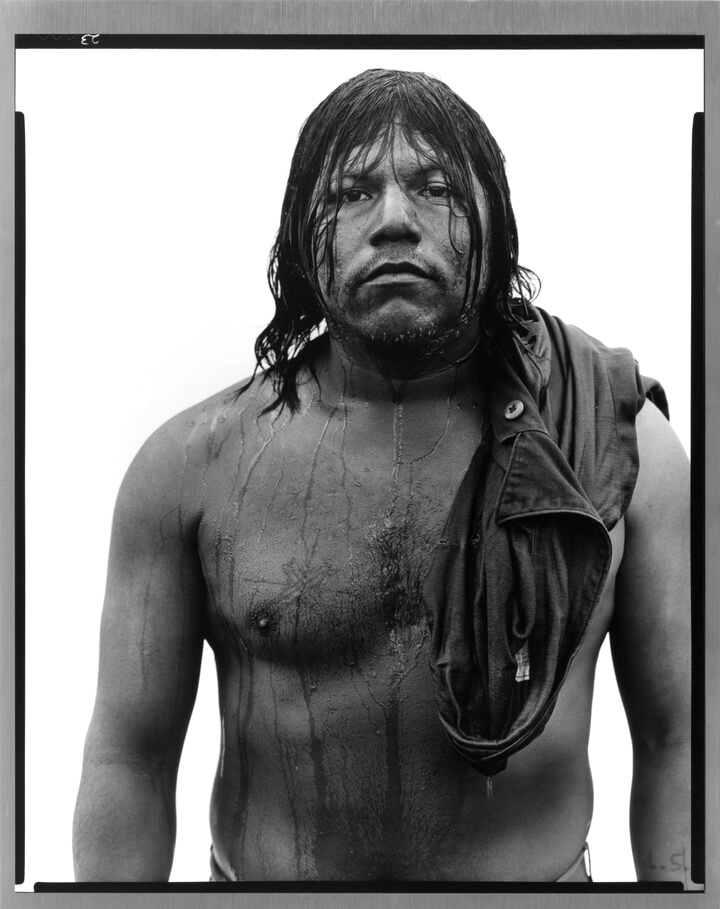

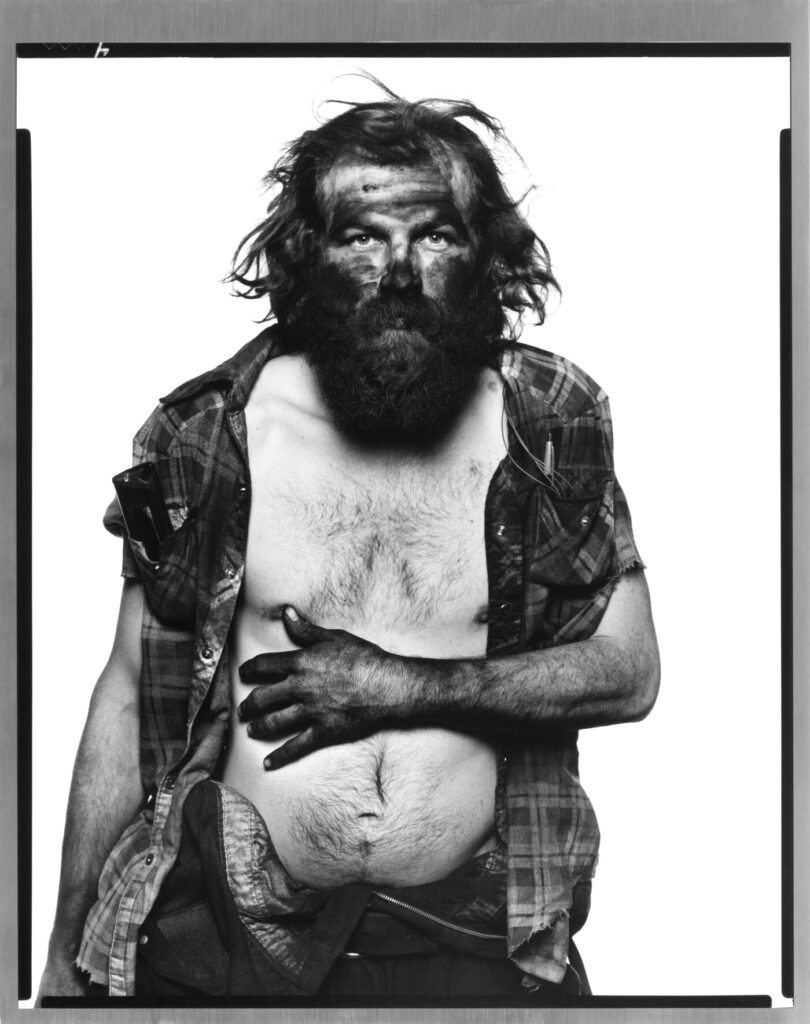

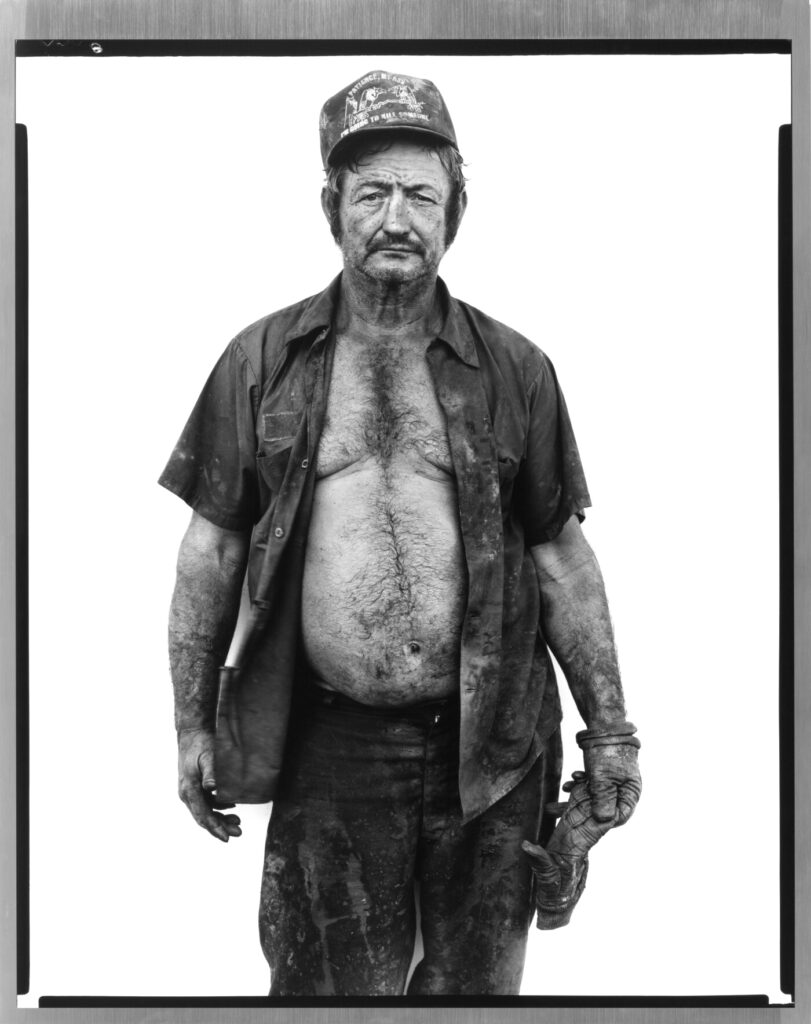

From 1979 to 1984, Avedon and his small team crisscrossed 17 western states, visiting 189 towns and photographing 752 people. He didn’t seek out celebrities or socialites; instead, he found his subjects in slaughterhouses, truck stops, fairs, prisons, and oil fields. Among them were drifters, miners, meatpackers, waitresses, ex-cons, and gas station clerks, all faces etched with the wear and work of daily life.

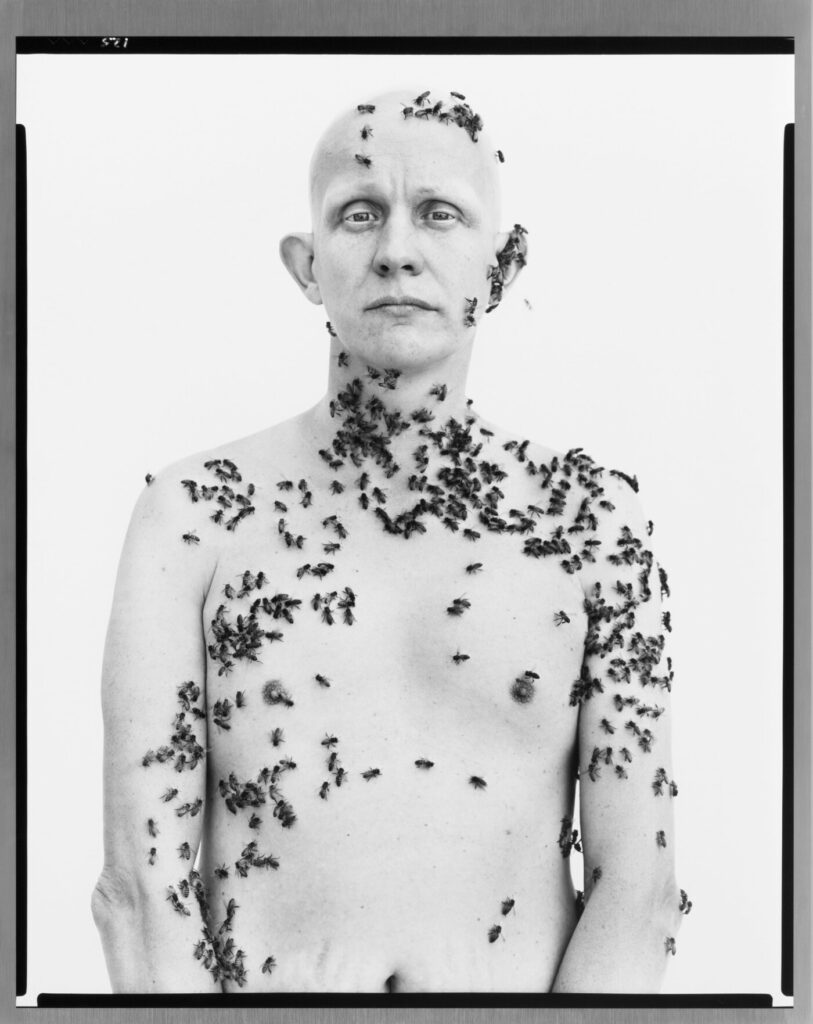

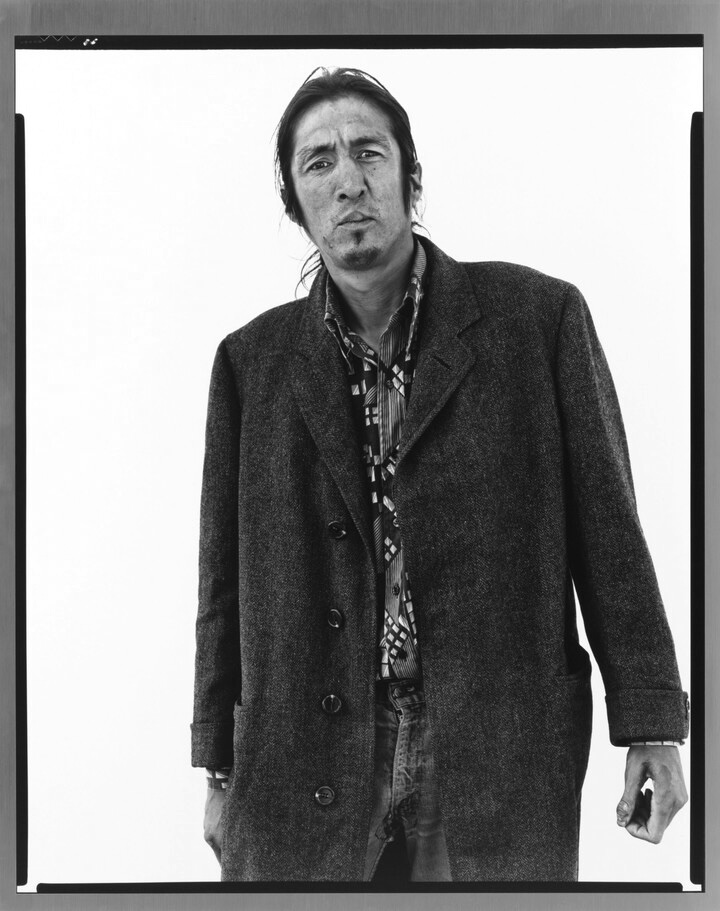

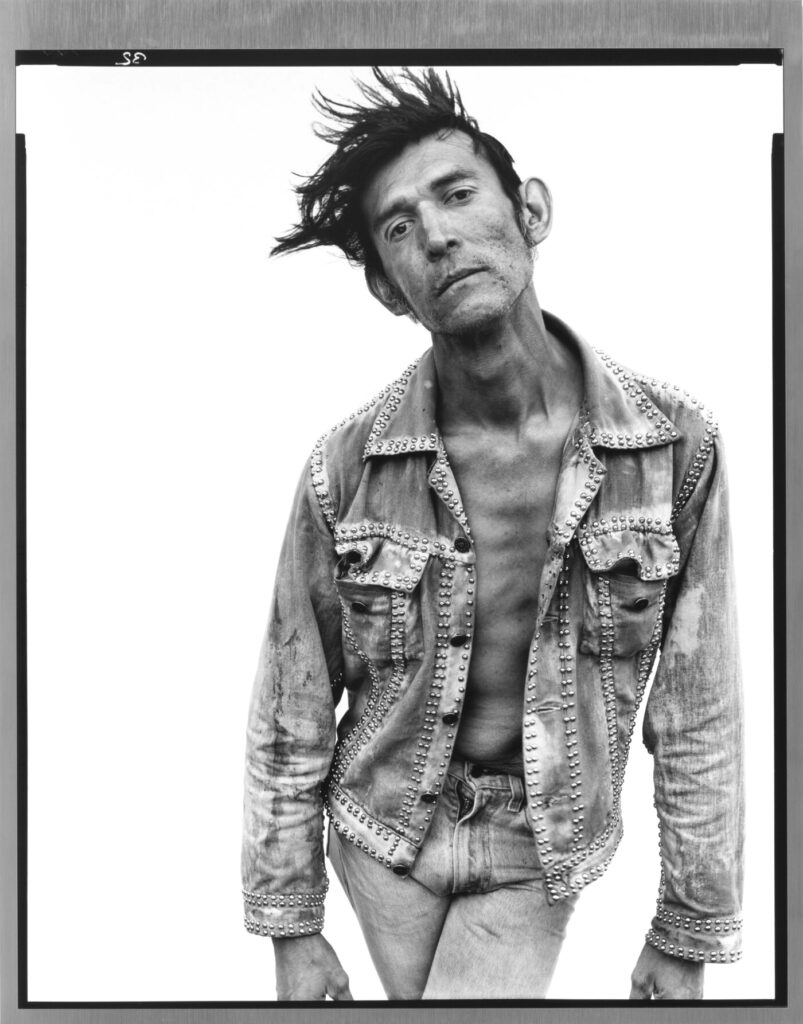

What made the series so striking was the uniformity of Avedon’s approach: every subject was shot outdoors, always in open shade, always against a stark white background that he transported from location to location. He used a large-format 8x10 Deardorff view camera, a slow, deliberate instrument that required the subject to hold still and engage directly. The camera was set on a tripod; the white backdrop isolated each person from their environment, removing narrative cues and leaving the viewer to contend solely with the subject.

The results were disarming. These weren’t sociological studies or documentary portraits in the traditional sense. They were confrontational, theatrical, sometimes uncomfortable. A teenager with black eyes and a nosebleed; a carnie holding snakes; a rancher whose face seemed carved from granite. Each figure became monumental. And because the background was blank, the subject had nowhere to hide.

Controversy and Intention

When the series was first exhibited and later published as a book, it ignited a storm of criticism. Avedon, a fashion photographer from New York, had ventured into working-class communities in the American West and returned with images that many felt were unflattering, perhaps even exploitative. Some accused him of aestheticizing hardship, others of being emotionally detached from his subjects.

Avedon countered with conviction: “These are my people,” he said in interviews. He wasn’t making fun of them or turning them into curiosities. He was trying to locate truth, not an anthropological truth, but a psychological one. His technique was methodical: he often shot 50 to 100 frames of a single subject, searching not for a smile or a performance, but for a moment when the subject let their guard down. He described it as something akin to finding the meeting ground between subject and photographer.

This wasn’t a project about poverty or regionalism; it was about American identity. Avedon saw these individuals not as “others,” but as essential figures in the nation’s story: tough, independent, strange, proud, fragile. In many ways, the series was less a document of the West and more a mirror held up to a rapidly changing America, where the myths of frontier individualism were clashing with the realities of economic decline and cultural fragmentation.

Behind the White Backdrop

Few people know that Avedon’s white backdrop itself became legendary. It traveled with him from state to state, providing a stage of visual neutrality that paradoxically emphasized each person’s uniqueness. But there’s a secret to it: the backdrop was rarely completely smooth. Creases, wrinkles, and even dirt would sometimes show up in the final prints, adding texture and imperfection, something that would’ve been unthinkable in his fashion work.

Equally revealing was Avedon’s practice of conducting long interviews with his subjects before photographing them. He wasn’t interested in rushing the process. He wanted to know their stories, their lives, their losses, their jobs, their dreams. Sometimes he paid them $25 for their time, sometimes more, and always treated them as collaborators, not objects.

The Archive and Afterlife

Out of the 17,000 negatives Avedon shot for the series, only 124 made it into the final exhibition and book. The contact sheets, however, reveal an obsessive attention to detail, tiny shifts in body posture, hand placement, gaze, tension in the jaw. The editing process alone took more than a year.

Today, In the American West is recognized as one of the most significant portrait projects of the 20th century. It resides in major museum collections, has been studied extensively by critics and scholars, and continues to influence contemporary photographers. Artists like Alec Soth and Katy Grannan have echoed Avedon’s approach in their own explorations of Americana.

In a strange twist, the very thing that drew criticism at the time, Avedon’s minimalism and detachment, now feels prophetic. In an age of selfies and algorithmic image curation, his portraits stand out for their patience, their stillness, their refusal to flatter. They’re reminders that photography, at its best, isn’t about showing people as they wish to be seen, but as they are.

Final Frame

Richard Avedon once said, “A portrait is not a likeness. The moment an emotion or fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion.” In the American West is full of opinions—quiet ones, brutal ones, empathetic ones. It’s a visual reckoning with the American myth, told not through heroes or outlaws, but through the faces of real people on the margins. People who, for a brief moment, stood in front of a white sheet in the middle of nowhere and became unforgettable.