In which we rediscover the overlooked trend of ASCII art hidden inside fan-made video game guides from decades ago, created at a time when just including screenshots was not an option in the era of dial-up connections.

In the late 1990s up until the early 2010s, if you needed help getting past a difficult level in a video game, you’d have a few options. Get your older brother to do it for you, call a phone number that on the back of your game manual, or go to the game store and buy a strategy guide that showed you how to beat the game. For those who didn’t have an older brother, phone privileges, or a ride to the store, there was still one option left: fan guides.

The fan-made plaintext game guides, hosted on sites like GameFAQs, NeoSeeker, and personal GeoCities pages were a notable staple of older gaming communities, intended to be read by players of all ages. In time, the fan guide outgrew its simple origins and formed a parallel canon to official strategy guides available from the stores.

Few thought of them that way at the time, they were just there when gamers needed them, but looking back, they were an entire shadow library of game knowledge that existed alongside the glossy, paid strategy guides behind shop counters. Aware of this, the publishers of the official guides often tried to compete with the community by publishing exclusive lore or developer commentary along with the guides. Sometimes, big fold-out posters were included. But it did little to help. The community guides were there to stay.

This ecosystem lived largely outside commercial publishing, shaped instead by message boards, email chains, early search engines, and chatrooms. For a lot of younger players from back then, these guides were an early introduction to long-form, user-generated writing on the internet: dense, practical, and written with the expectation that you’d actually sit down and read, rivaled in length only by the stories from fanction websites.

Before sophisticated visual-heavy wikis provided a general exposition of the game and its contents, individual fan guides carried the voice, priorities, and peculiar fixations of its author, and gamers learned to recognize good ones by feel as much as by usefulness. Looking back on them over two decades later, the most notable qualities are the ways the authors of these guides attempted to provide a certain flair through illustrating them, despite having a limited set of tools at their disposal.

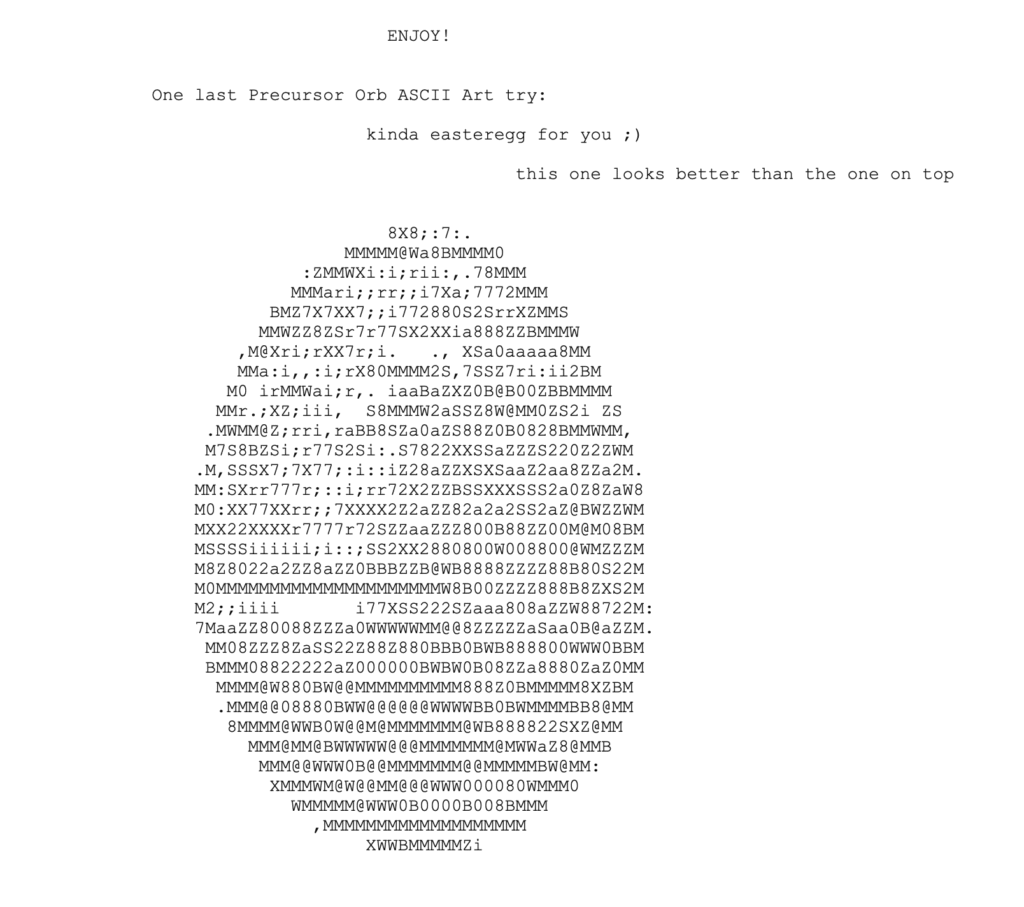

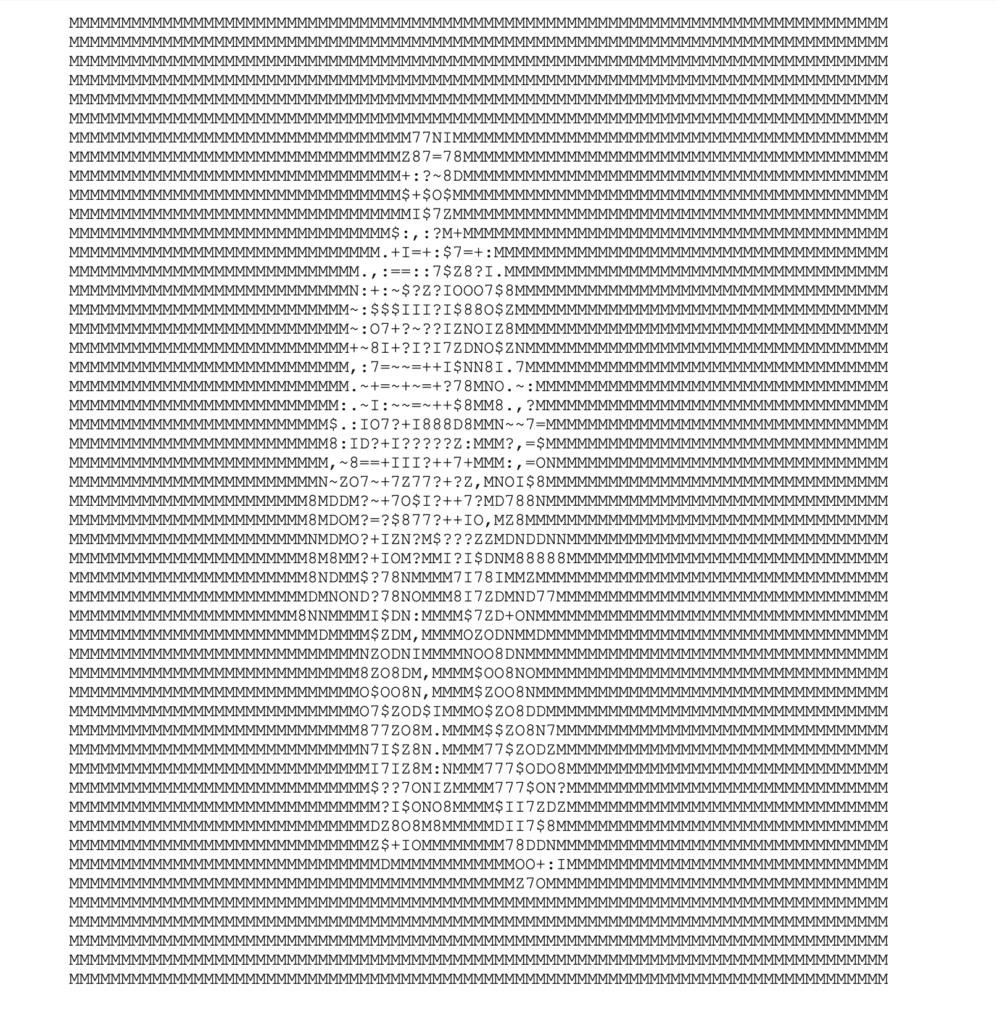

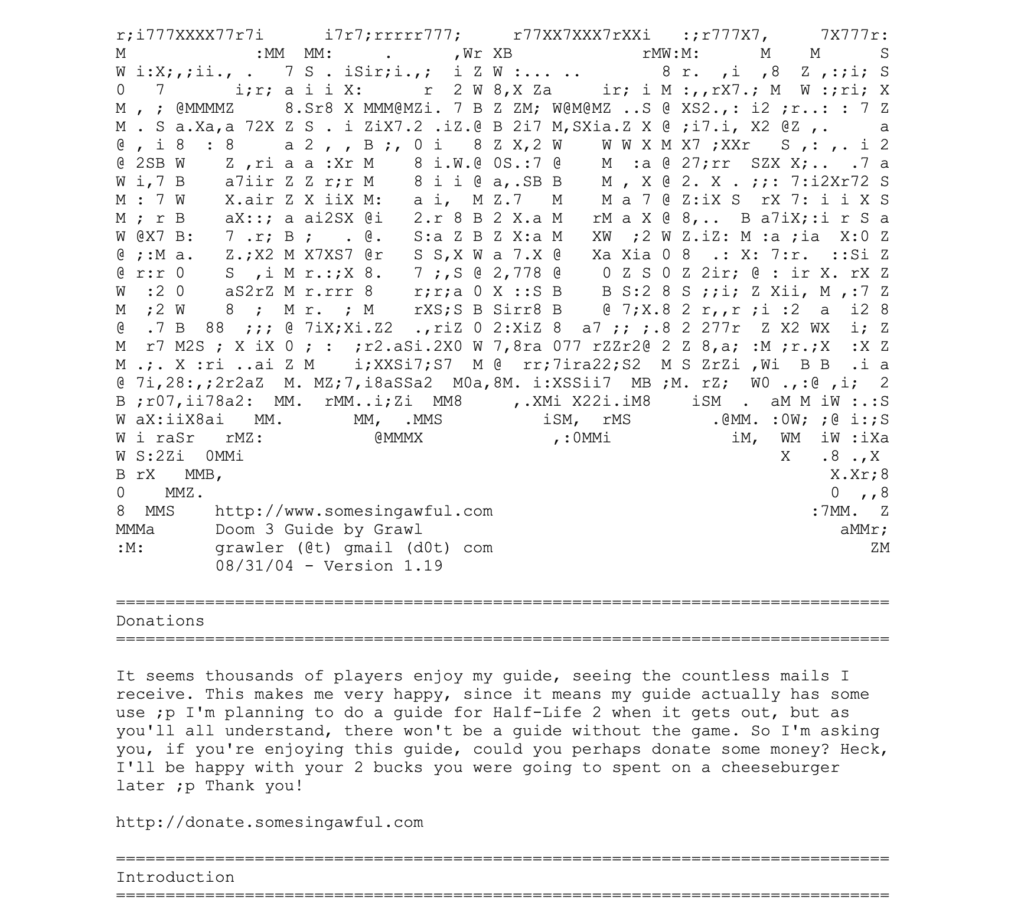

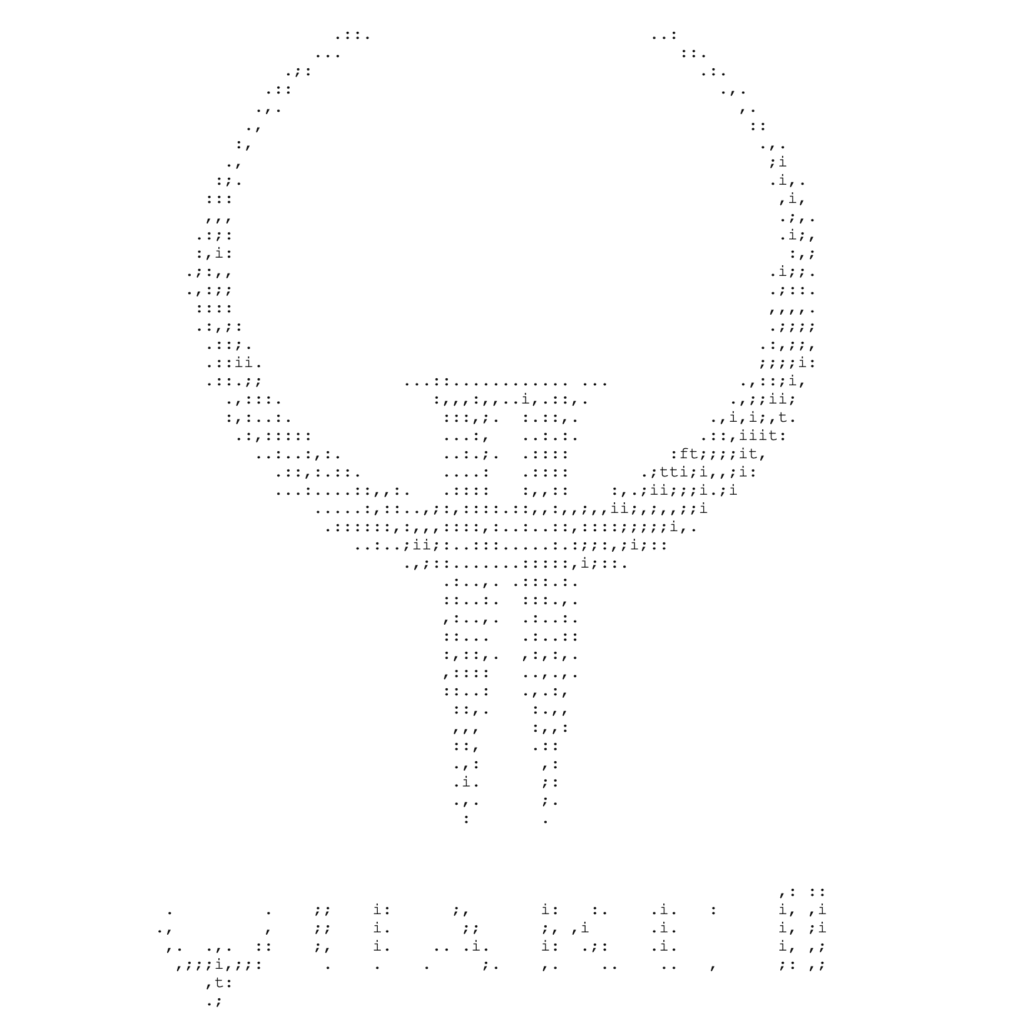

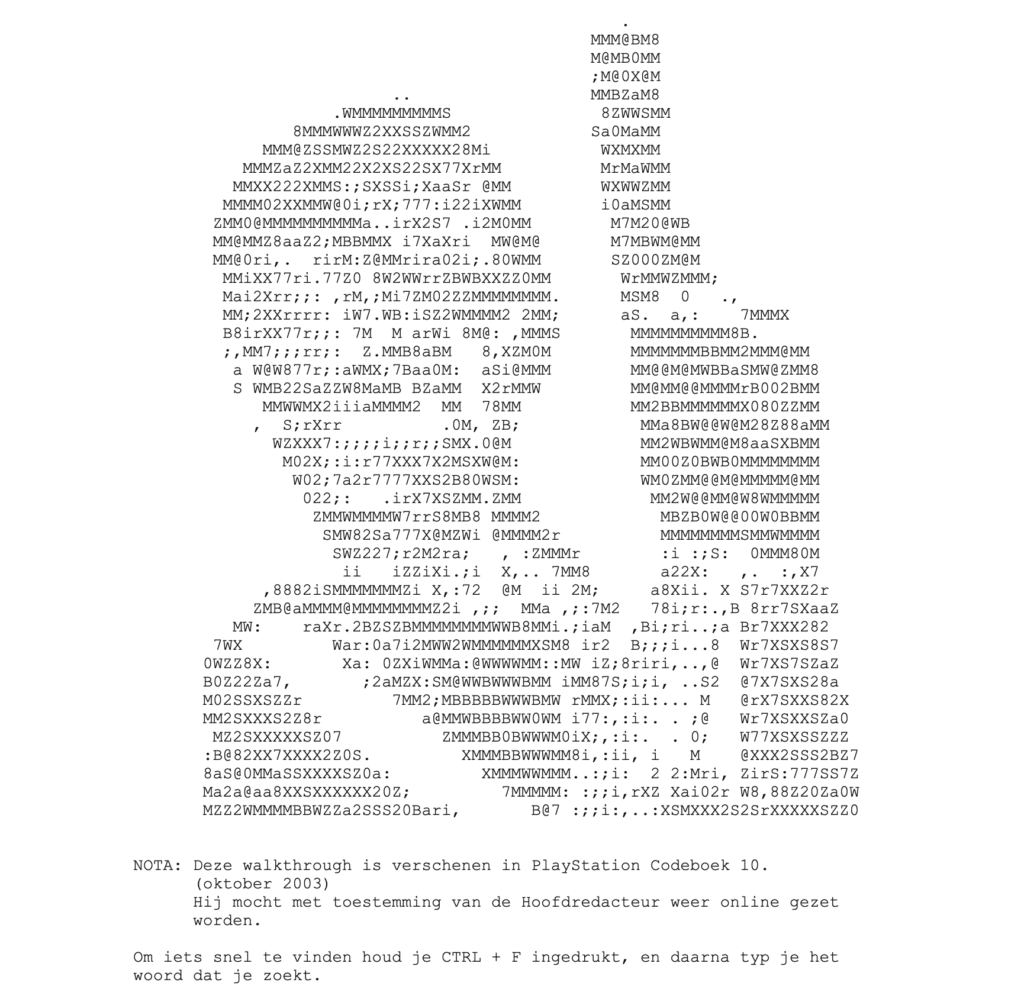

Stripped of images, formatting, and sometimes even punctuation, these walkthroughs were built to load instantly on dial-up and to survive being printed on cheap home inkjets. Within those limits, ASCII art emerged as a quiet flex, usually in the form of an elaborate portrait of the main character or the game’s logo rendered in letters, numbers, and symbols right at the top of the guide.

Upon noticing one of the illustrations for the first time, it might have felt strangely intimate, as someone had sat there, nudging characters into place, not because they had to, but because they wanted to give the reader something to look at. It was digital folk art, born from limitation and a desire to leave a personal mark on your work, similar to the user signatures of old message boards.

The technical constraints mattered more than many would realize at the time. Everyone was working with the same one font, line width and height was uniform, and authors frequently warned you not to open the file in word processors that would wreck the alignment. A clean, well-rendered ASCII header meant the guide was going to be more serious than the other ones.

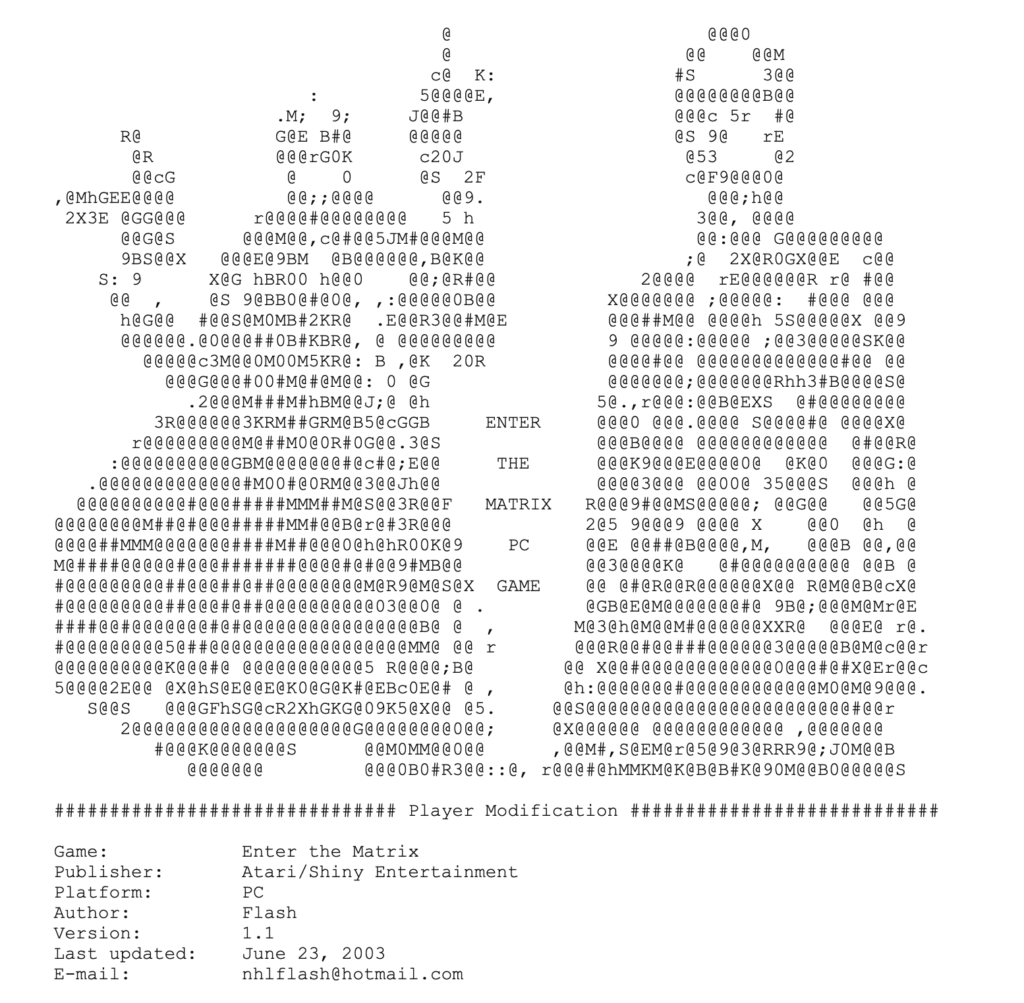

These guides were usually published under handles, yet they were obsessively maintained, versioned, and corrected through email feedback. Some authors included full changelogs, legal disclaimers, and warnings about plagiarism, because copying and reposting a text file, especially the ASCII art, without permission was the original sin of early game guide culture. Reading those warnings now feels almost quaint and ironic (considering the point of this post), but at the time they underscored how personal these documents really were.

Content ownership online was murky and enforcement was basically nonexistent, so authors relied on social norms and reputation to protect their work. Being credited correctly, or discovering your ASCII art had been lifted, mattered deeply. Many guides opened with stern, half-theatrical warnings that read like a mix of legal notice and wounded pride, which only made it clearer how much unpaid labor had gone into them.

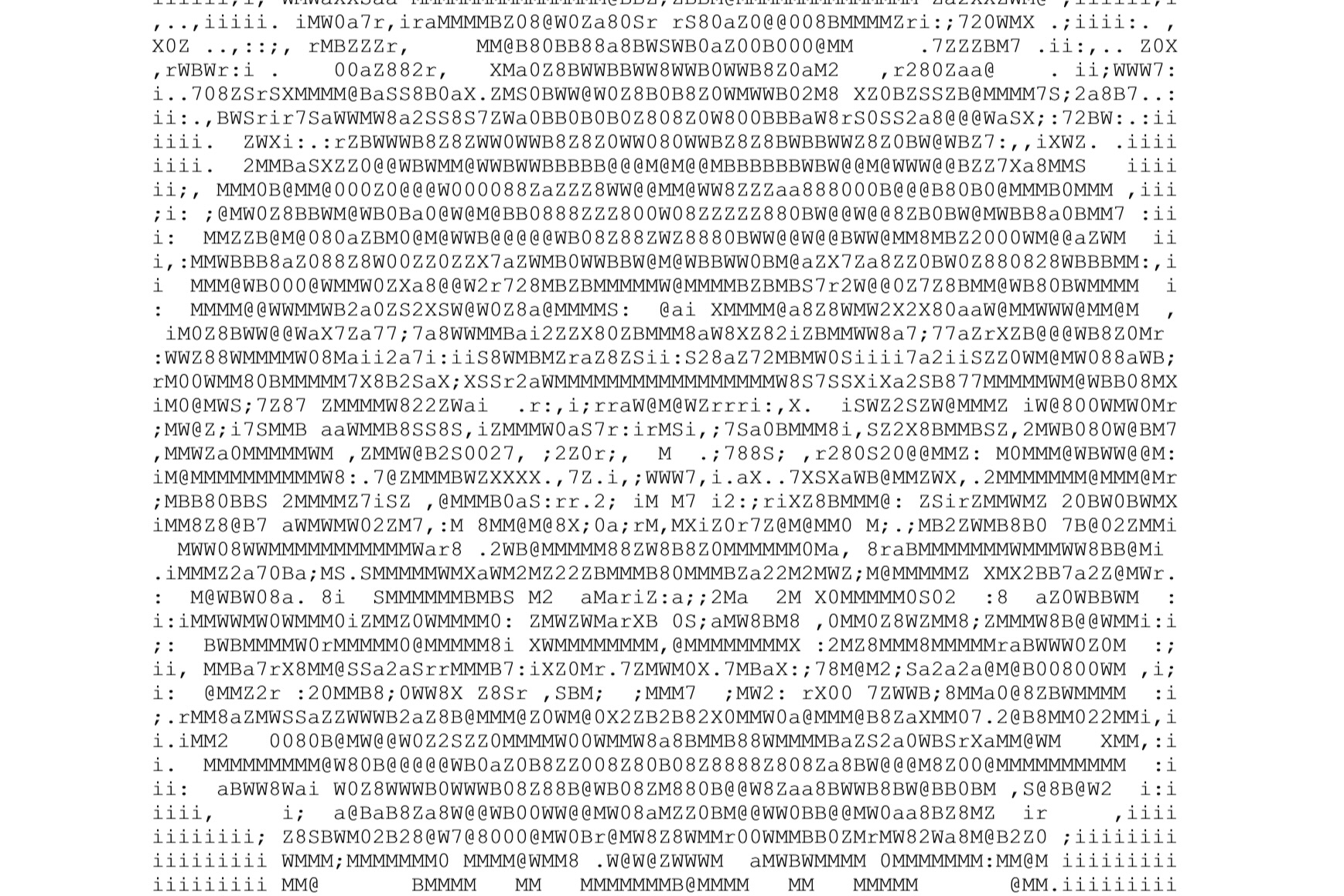

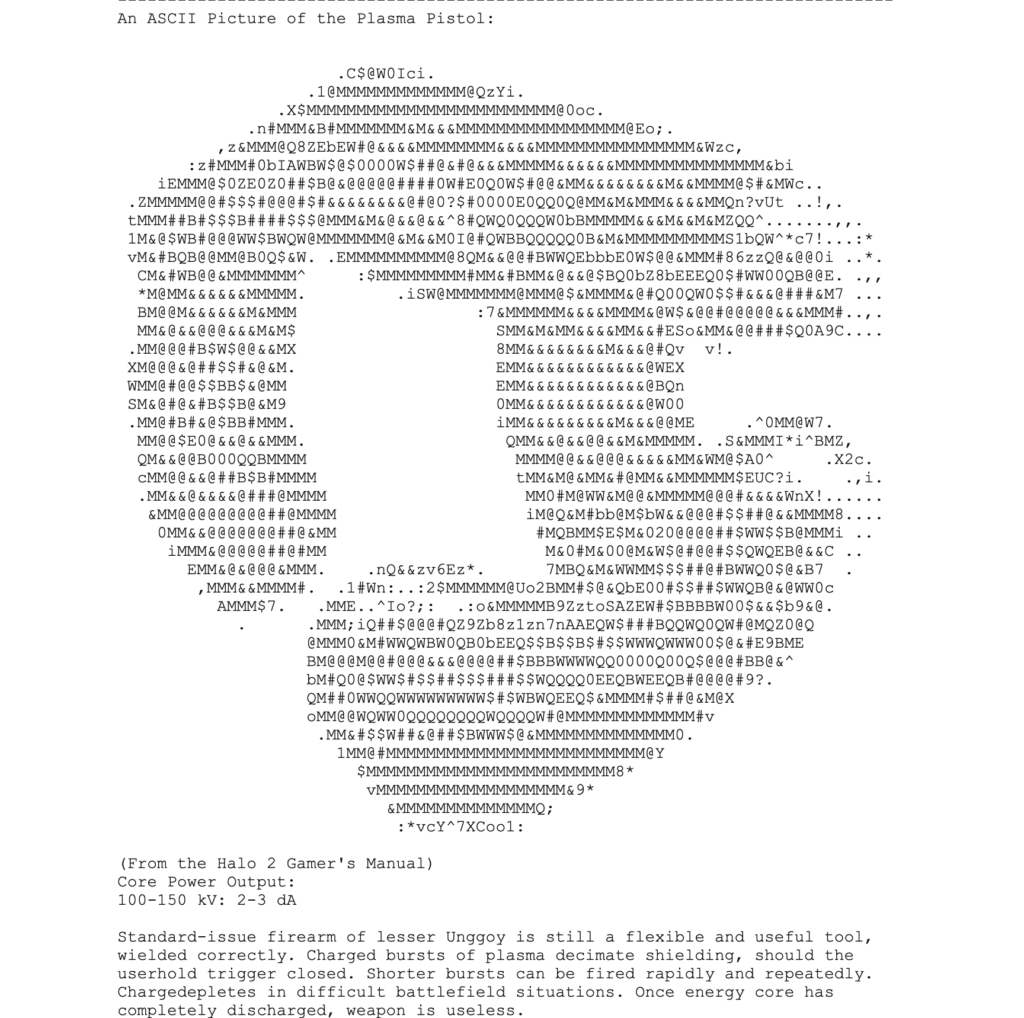

ASCII diagrams weren’t decorative alone; often times they solved real problems. Before in-game maps were common or detailed enough in a way that helped, a neatly aligned grid of characters would explain in-game geometry or strategy more clearly than using those characters for words ever could.

Level layouts, controller button schemes, puzzle logic, enemy patrol paths, even timing-based mechanics could be frozen into text in a way screenshots were supposed to, but couldn’t due to the constraints of using plaintext. These diagrams demanded slow reading and rereading, and gamers were expected to visualize space and systems rather than simply copy what someone else did on screen.

Today, streamers, YouTube playthroughs, and tutorial clips have replaced the slow intimacy of reading a guide line by line. When players get stuck now, they watch someone else solve the problem in real time instead of scanning a text file for the exact sentence they need. As a result, the ASCII-embellished fan guide has become a dying art form, still archived, still searchable, thankfully, but new guides are rarely being put together now.

Gone the way of the fabled physical game manual, what’s been lost is a specific relationship to games: one where help arrived as dense text, hand-crafted diagrams, and the awareness that somewhere, a stranger had spent dozens of unpaid hours turning their obsession into a document for anyone patient enough to read it.