In an era when digital algorithms can summon nearly any song on demand, the late Rutherford Chang’s obsession with a single album, The Beatles’ 1968 self-titled LP, universally known as The White Album, felt like a deliberate act of analog rebellion. His long-running conceptual project, known as We Buy White Albums, is less about The Beatles and more about what happens to objects, and the lives that pass through them. It’s one of the most quietly radical record collecting experiments in modern art.

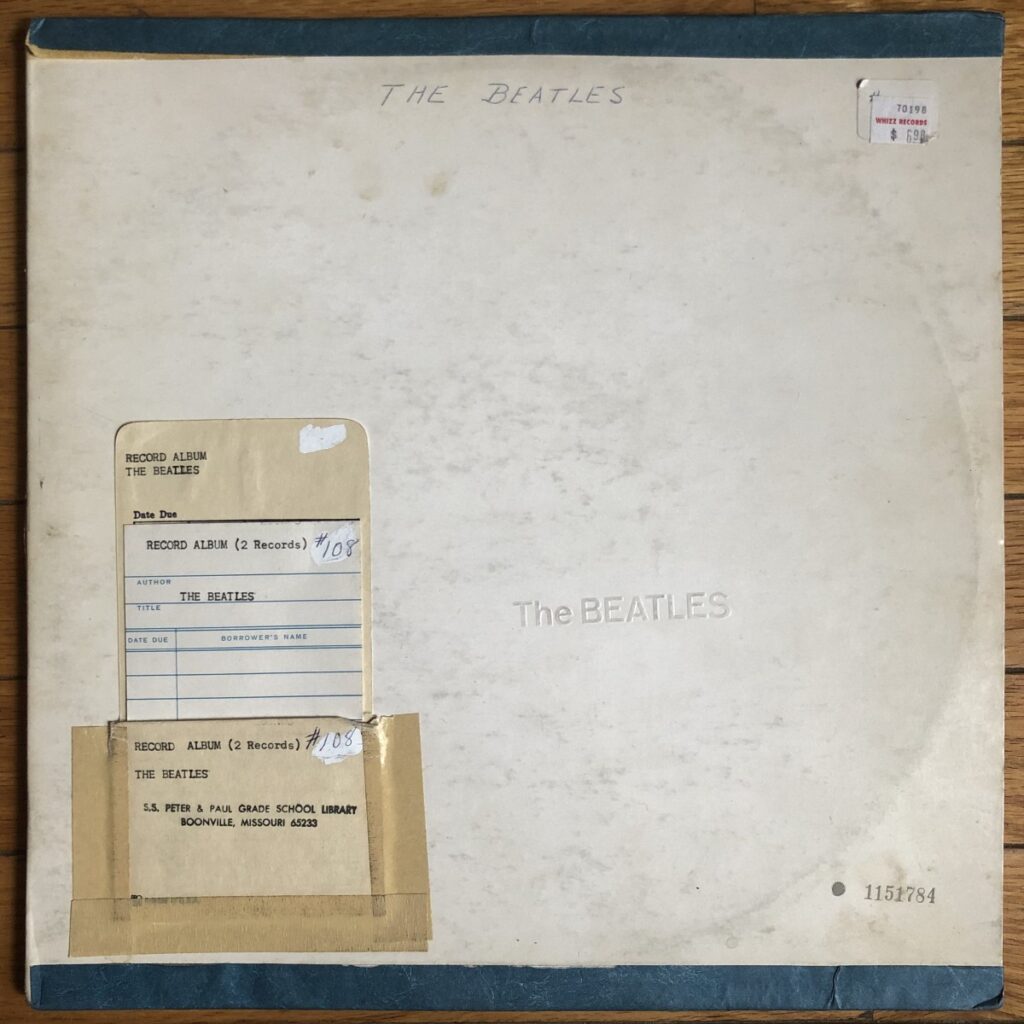

Launched in 2013 as a pop-up installation at Recess Gallery in New York City, We Buy White Albums took the form of an uncanny record store, with a catch. Chang’s shop doesn’t sell records, it only buys them. And not just any records. Specifically, first U.S. pressings of The Beatles’ White Album, identifiable by the stamped serial numbers on their otherwise featureless white covers.

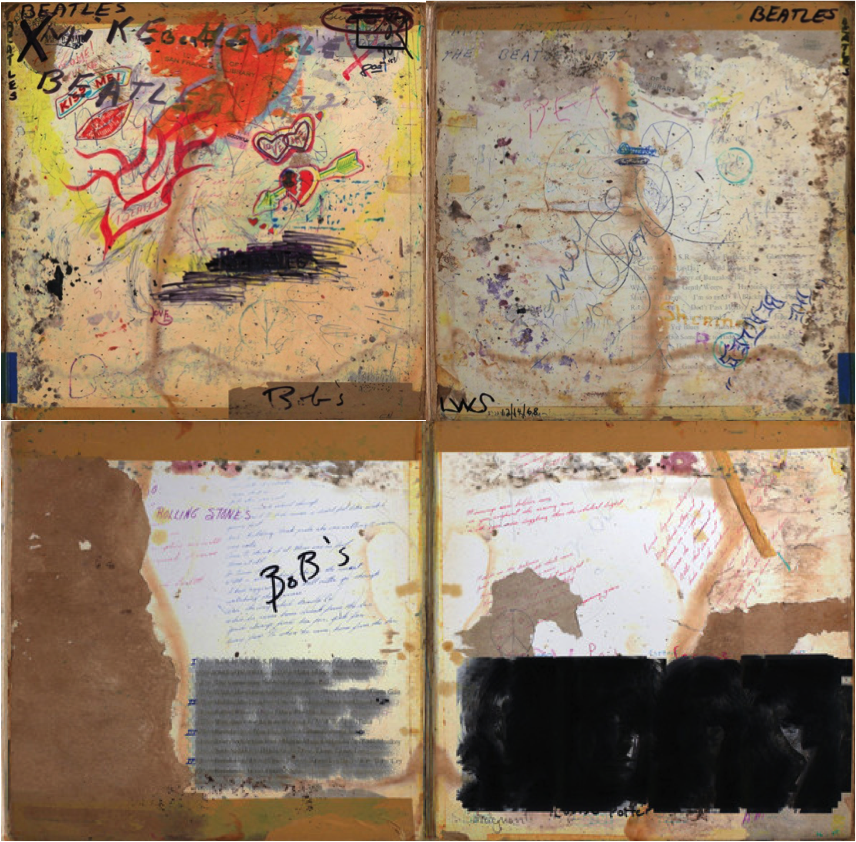

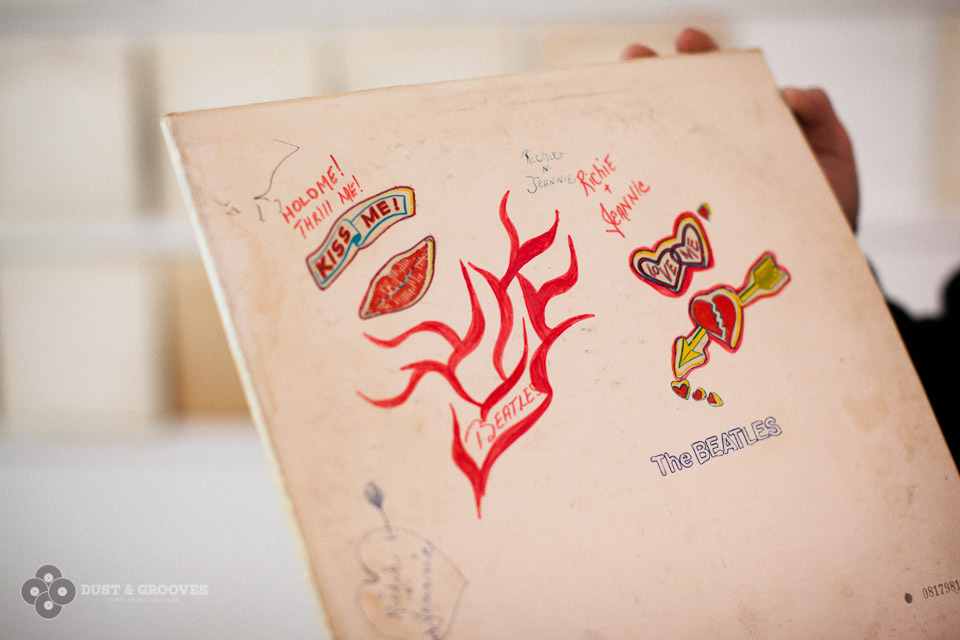

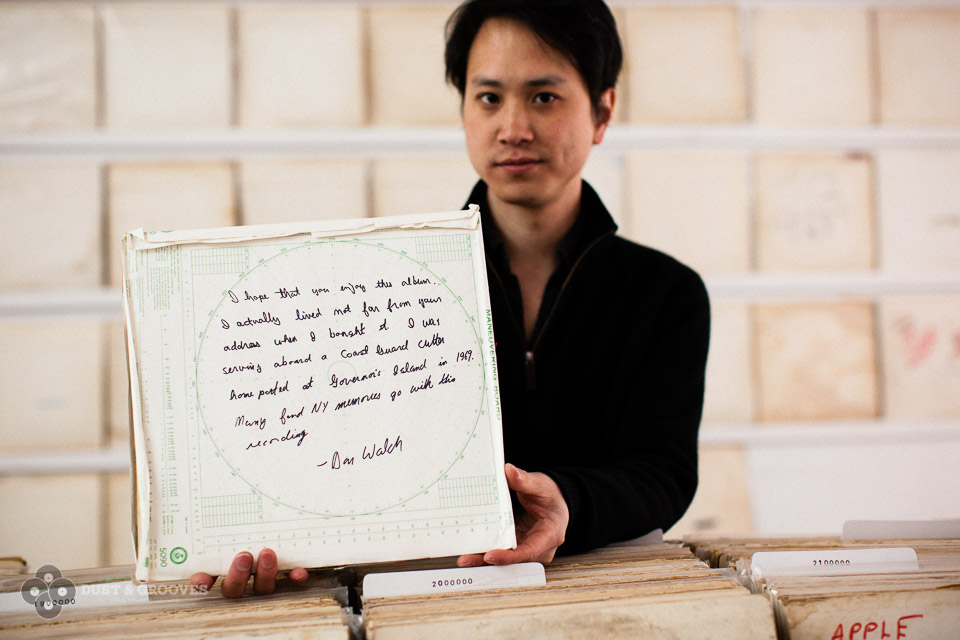

Inside the gallery, pristine racks and shelving overflowed with what appeared to be the same record, repeated endlessly. But a closer look revealed subtle, and sometimes profound, variations: yellowing from sun exposure, water damage, personalized doodles, lost stickers, mold blooms, and scribbled messages to former lovers or long-dead friends and relatives. Each copy, though mass-produced and originally indistinguishable, has become a unique artifact of time and use. Chang calls the project a “store,” but it’s as much a meditation on entropy as it is a collection to be bought or sold.

Thousands of Copies In One Place

When the original installation opened, Chang had some 700 copies, having been steadily collecting them since he bought his second copy when was 15 years old. By the time of his untimely passing in January of this year, Chang had acquired at least 3,502 copies of the White Album (with each one of those documented and uploaded to his instagram @webuywhitealbums), making his collection possibly the largest known accumulation of a single edition of a commercially released album, and he showed no signs of winding down his obsession.

Each album was documented, archived, and often displayed spine-outward to showcase the serial numbers, an inversion of the collector’s usual desire to spotlight cover art or mint condition. Here, the wear is the point.

Sonic Layering: A 100-Album Sound Collage

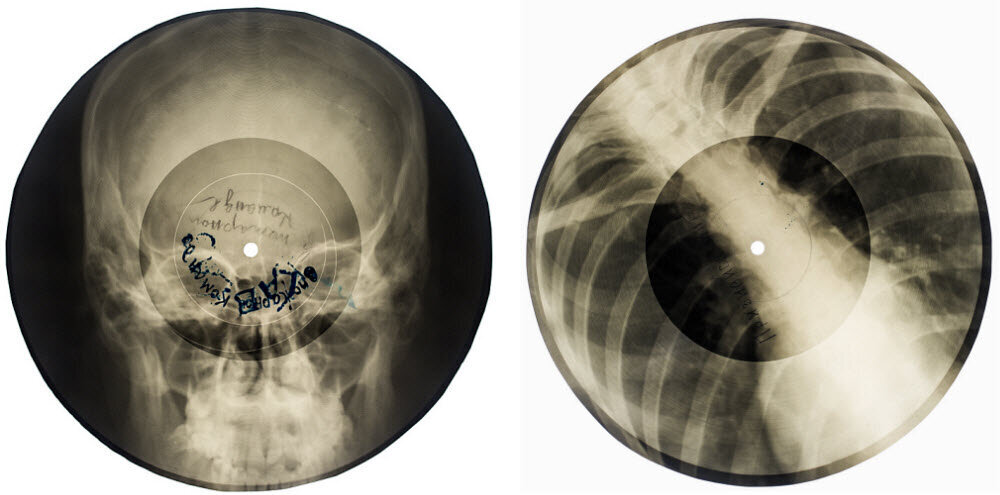

Beyond the visual impact, Chang’s project also lives in sound. In 2013, he created a layered sound piece by simultaneously playing 100 different copies of The White Album, each one having been chosen by visitors to his original installation. The result is a ghostly, warped version of the familiar song, voices phase in and out, tempos wobble, scratches interrupt. As you play the piece, ‘Back In The USSR’ sounds recognizable, if a bit tinny, but further through the first side everything goes awry, as the individual manufacturing imperfections, wear, dust, and so on cause the sound to skip, alter, and fall out of sync with the other instances of the album. It sounds like The Beatles, but submerged in the static of time. Many have compared it favorably to James Leyland Kirby’s (better known as the Caretaker) musings on memory and the passage of time as well as William Basinski’s experiments with sound, most notably his Disintegration Loops.

This multitrack collage was pressed into its own limited-edition vinyl release of 800 copies, with the cover itself being the result of the 100 originals being superimposed on one another, effectively turning a commercial pop object into a deteriorated sonic sculpture and visual collage.

An Archive of Mass-Produced Individuality

Chang’s project flirts with the language of museum curation, pop culture detritus, and fan obsession, but it lands somewhere more unexpected: accidental anthropology. The White Album, originally conceived by the Beatles as a blank canvas of sorts, an anonymous sleeve containing an overwhelming range of musical styles, becomes even more of a mirror in Chang’s hands.

Each copy he buys offers a tiny, unintentional autobiography. Owners wrote their names on them. They drew peace signs or hearts. They added stickers or obscured the band name with ink. Some played them to death; others seemingly let them sit and collect dust, unused. Some used them as coffee cup coasters, one copy even has a cigarette burn all the way through the vinyl. “Poor condition albums are not necessarily more desirable,” Chang said in an interview, “Rather it’s the differences between every unique copy in this massive edition that make the collection interesting.”

In collecting these physical traces, Chang is also gathering stories, unwritten, but legible in wear and scuff and Sharpie ink. One copy seemingly has autographs from all of the members of the band, with the only caveat being the autographs all have the same writing; other copies have love letters written on them, and still others have breakup letters, but the latter both further hint at how often this record in particular, has intentionally changed hands over the years, a sort of literal cultural currency.

While the platonic ideal of this project would be to collect all of the copies out in the world, Chang realizes it’s an impossible task, and regardless, he claimed he never spent more than $20 on a single copy. Most of the work was finding people to acquire the album from and convincing them to part with their copy.

Since hearing the news of Chang’s passing, many people took to the internet to recall their encounters with the artist, whether in person or over email, during which they sold him their copy of the record, with many mentioning how inspired they were by Chang’s vision behind the project and his steely dedication to the album.

Why The White Album?

Why this album in particular? The White Album, released in 1968 at the height of The Beatles’ global fame, is arguably one of the most over-pressed records in history. Out of the original pressing, there are least three million surviving copies out there, according to Chang. Each of those original pressings bore a unique number. That serialization, combined with the unadorned white cover, made it ripe for reinterpretation. Minimalist, mysterious, and nearly blank, the record invites customization, degradation, and projection.

Moreover, The White Album is famously eclectic, containing both Lennon’s harsh experimentalism, McCartney’s soft pop, Harrison’s mysticism, and Ringo’s singalongs. It’s a record of contradictions, and so too is Chang’s project: orderly in appearance, chaotic in meaning.

Organized by Nature

The project itself is a reflection of Chang’s overall philosophy and lifestyle, that of being a collector and an archivist, and this reflects in his personal life as well as his other projects. As a collector, Chang got his start early as a schoolchild, when he took the small stickers attached to fruit at the supermarket and attached them to his binder. From then on he continued to collect, working his way up from hotel stationery, postcards, baseball bats, and receipts (not for tax purposes, but merely to keep) all the way to his career collecting objects as a conceptual artist.

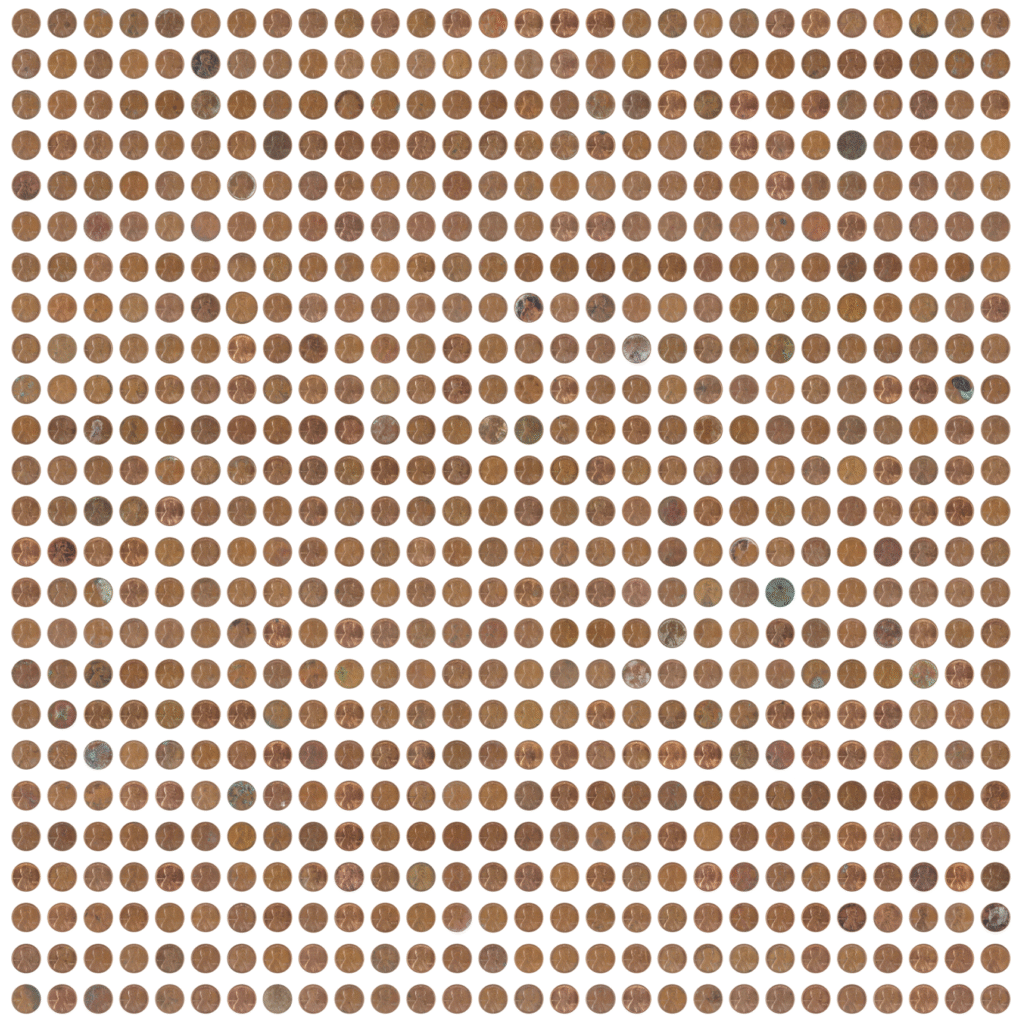

One of his other notable projects is Cents, a 2017 project in which he collected 10,000 pennies from the years of 1910–1982, ending just before the US mint stopped casting them in copper (today’s pennies are mainly cast in zinc), and proceeded to photograph and catalogue each one. After that was completed, he encoded each image of a penny as a satoshi, the individual ordinal for bitcoin, or in layman’s terms, the pennies of cryptocurrency, effectively creating tradable NFTs out of them (remember those?). The pennies themselves he melted down and forged a 68-pound cube with them which later sold for $50,400 at an auction last June. Not a bad return on investment. The project is all the more poignant now, considering the US government’s re-evaluation of the worth of a penny following the US Mint’s announced plans to phase out the penny from production next year.

Other projects of Chang’s involve rearranging newspaper text in alphabetical order, collecting the megaphones of Beijing street vendors with pre-recorded announcements (and cacophonously playing them all at once), and livestreaming all of his attempts at becoming the number one globally ranked tetris player, reportedly reaching the rank of number two, only to be disputed by none other than Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, who claimed he nevertheless reached a higher score in the past.

As an archivist, Chang is a believer in maintaining systems and distances himself from any charge of being a hoarder (he’s referred to his apartment as “meticulously clean”), arguing that the difference is in his approach to collecting. All of these attempts nevertheless circle back to Chang’s attempts to bring attention to the mundane, to zoom in and try to document the details of everyday existence that may not be readily apparent from a distance.

Notably, Chang also came to the realization that even our interactions with these objects as observers can anchor us to specific moments in time, as he discusses in one interview, referring to his habit of collecting every single receipt for over a decade (as well as creating a list to keep track of every flight he’s ever been on), he began to look at them as “diary entries” and subsequently noticed, as well, that the “White Albums are starting to have memories associated with them too. I can remember actually, it’s strange but yesterday, when I was setting them up, putting them in the record bins I was reminded of times and, on occasion, when I bought them.” In other words, it’s quite possible that you, the reader, will one day remember where you were when you read this article, or I, the writer, will remember where I was when I wrote it, and it seems that this feeling of remembrance is the essential mission behind Chang’s collection.

A Living, Growing Artwork

Since its inception, We Buy White Albums continued to grow through the years. Chang has brought versions of the project to Liverpool’s FACT gallery, Taipei’s MoCA, and beyond. In each installation, he reshaped the space into a hybrid of retail environment, listening station, and living archive. Visitors were invited to flip through the records or listen to them on turntables, or even sell Chang their own copies of the record to add to the collection, turning the exhibit into a participatory experience.

In the age of digital music, where everything is available and nothing is physically touched, Chang’s collection reminds us that physical media is haunted by its owners, its conditions, and its travels. He turns a symbol of mass production into a study of impermanence, turning a pop object into something quietly elegiac.

Final Thoughts

Rutherford Chang’s White Album project is more than an art installation, more than a collector’s eccentricity, and more than a Beatles tribute. It’s a profound exploration of repetition, memory, material decay, and human traces left on culture’s most durable artifacts. As his archive grew, so too did its meaning: a thousand albums, all the same, all completely different.

What will happen to the collection now is wholly unknown at the time of this writing, perhaps they will once again be sold off to collectors, or ideally the record store finds a permanent location where the albums can be listened to in perpetuity. Either way, the stories of these objects will continue, it’ll be up to us whether we choose to listen to those stories.