Two thousand years before concrete brutalism, this ancient Roman tomb built to honor a former slave appears staggeringly modern, but the real story reveals how labor, technology, and ambition reshaped architecture outside Rome’s elite traditions.

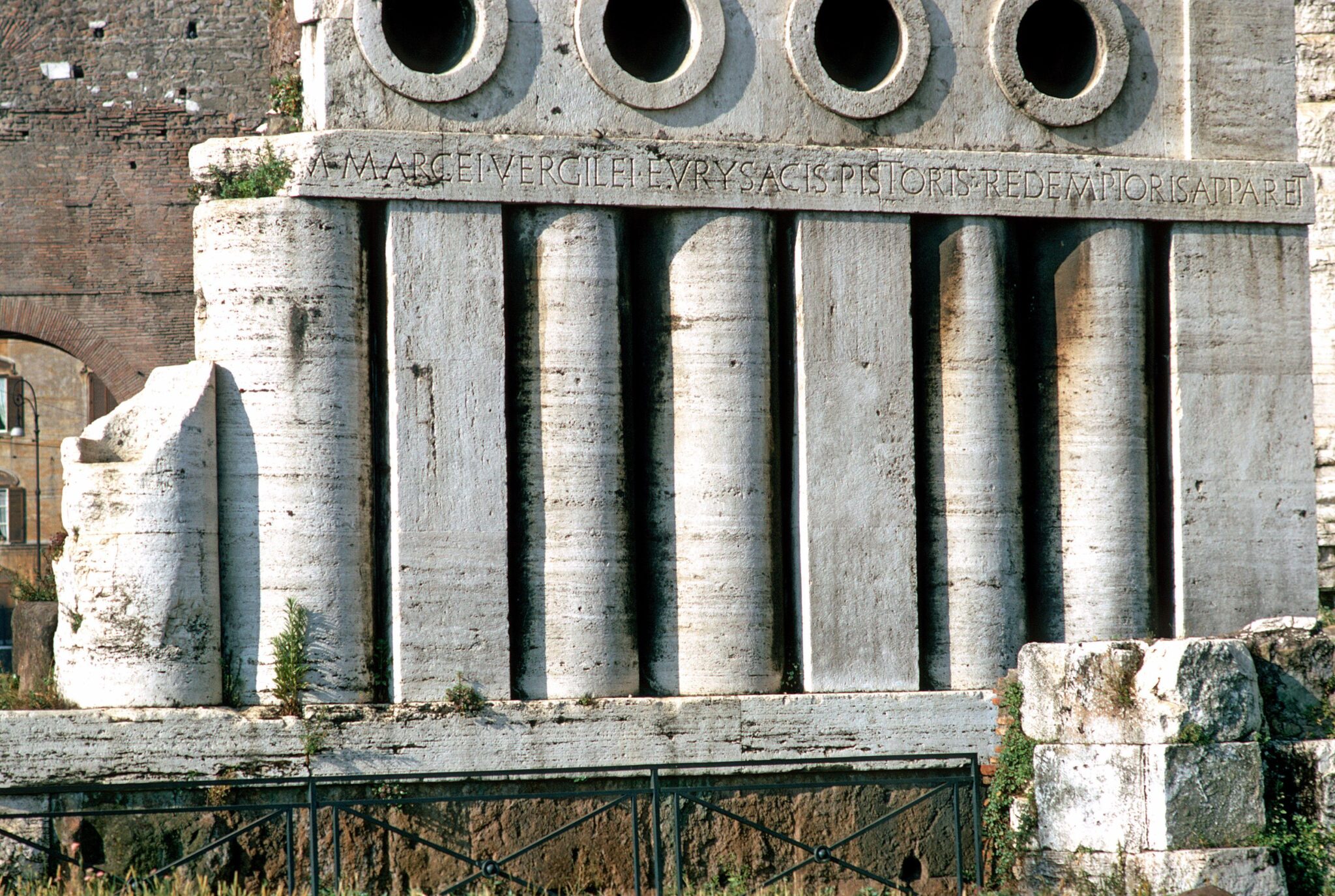

Tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces, an ancient landmark beside Rome’s Porta Maggiore and one of the historical entrances to the ancient capitol, sits like a mislaid fragment of the twentieth century: a sharply-defined mass of pale stone with unbelievably simple geometry and seemingly stubbornly indifferent to classical grace. Yet it is a structure with global importance, one of just a few surviving examples of funerary architecture in Rome not made by its elite.

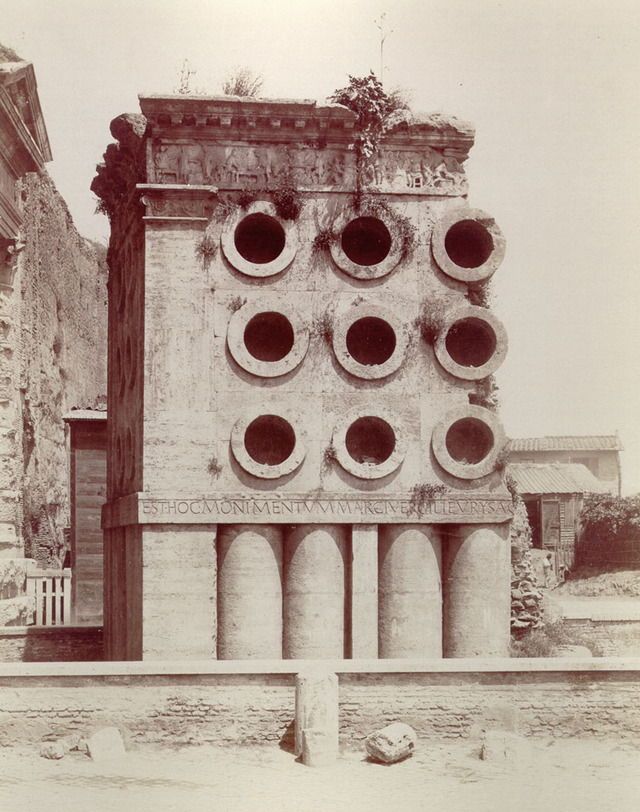

Its surfaces are not smooth and insistently literal, its geometry based on repetition rather than harmony. Visitors will immediately notice the smooth columns, set down without any space between them, as well as the cylindrical recesses right above them. To our modern eyes, the ruin has more in common with postwar civic infrastructure or a concrete silo than anything rooted in the principles of Roman architecture.

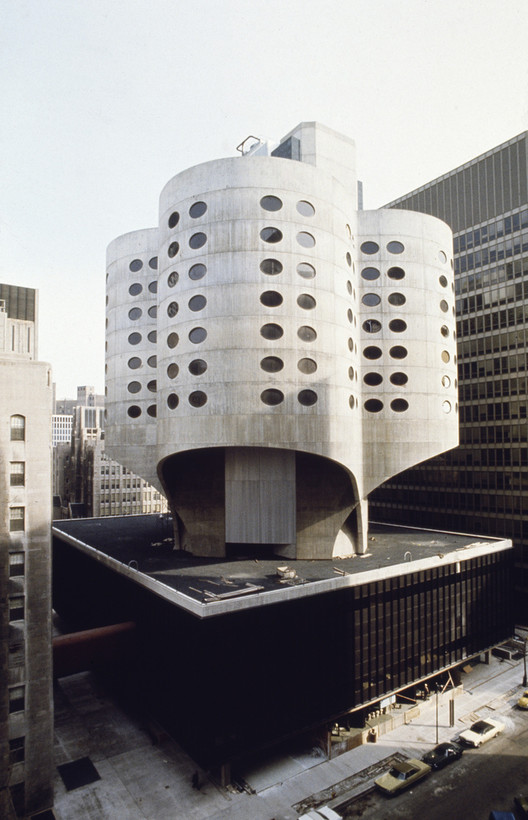

It reads uncannily like a prototype of brutalism, an often maligned syle of architecture that foregrounds mass, function, and material over beauty, symbolism over elegance, and presence over persuasion. Looking like a miniature combination of Bertrand Goldberg 1975 Prentice Hospital and the Lauchhammer Bio-towers from 1958, the visitor would be forgiven for assuming that this was an ancient industrial structure rather than a tomb, and they’d be partly right.

The monument is generally believed to date from 30–20 BC, a period when Roman architecture was increasingly codified around Augustan ideals of order, proportion, and revived classical taste. Against that backdrop, Eurysaces’ tomb looks like an installation aggressively out of time and space. Instead of Corinthian refinement or mythological reliefs, the structure is defined by a rhythmic series of large circular openings punched into its upper walls.

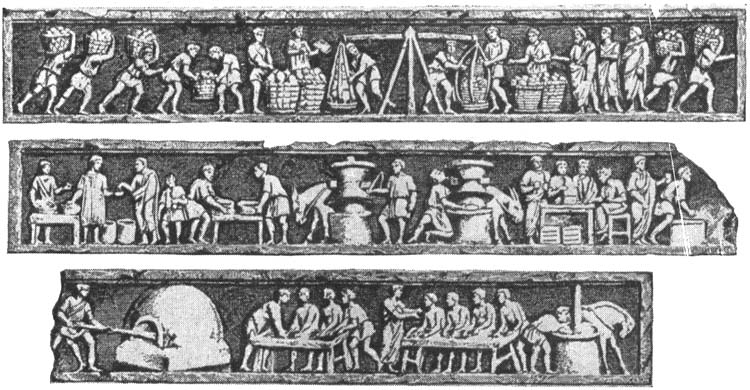

These voids, stacked and repeated with mechanical regularity, are minimal and abstract in their presentation. Just above them, right where the tomb meets the sky, are thin reliefs, not of mythological scenes (as was the custom), but of simple labor: vignettes from a large-scale bakery, a testament to the craft which gave the tomb’s owner his wealth and freedom. In fact, its believed the entire tomb was built to resemble an ancient dough kneading machine. The man the tomb is dedicated to was a baker. Naturally, it is often unofficially called the Tomb of the Baker.

The tomb is remarkably well preserved, with three of its original four façades surviving largely intact due to an unusual historical accident: the construction of the Aurelian Walls in 271 AD, which completely enclosed the monument and protected it until 1838. Only then, during large-scale excavation and demolition works, was the tomb freed from the surrounding masonry.

Its sculpted frieze is a textbook example of what art historians call the Roman “plebeian style,” a non-elite artistic tradition associated particularly with freedmen and spanning roughly from the first century BC to the fourth century AD. This style favors simplified, often blocky forms over classical naturalism, privileging clarity of narrative and legibility above refinement. Figures are rendered with short, stocky proportions, surfaces rely on incised lines rather than subtle modeling, and scenes frequently depict everyday labor and daily life rather than myth or heroic idealization. For context, a close modern equivalent in style and mindset would be the American New Deal art of the 1930s.

Within its immediate context, the tomb would have stood out sharply from neighboring monuments due to its unusual mix of materials and its highly unconventional decorative program, which is consistently repeated across all three surviving sides. Structurally, the monument is built around a concrete core filled with tuff (a form of rock made of consolidated volcanic ash) and faced externally with travertine slabs.

Quarried locally near Rome, tuff forms the structural base and contributes significantly to the monument’s stability, while the lighter-colored travertine provides a more refined exterior surface that contrasts in both texture and tone with the rougher internal material. Marble appears only sparingly, reserved for high-relief inscriptions and sculptural details, where its finer grain and whiteness add subtle visual emphasis within an otherwise utilitarian material palette.

The choice of travertine plays an important aesthetic role beyond durability. Its naturally pitted, honey-colored surface creates a rhythmic play of light and shadow that distinguishes it from the smoother marble insets, enriching the monument’s visual complexity without the use of paint. This restrained yet texturally expressive approach to ornamentation was atypical for tombs and monuments of the period, which more commonly relied either on plain masonry or on lavish imported marble.

The structure, built atop a low, undecorated socle (a plain low block serving as a foundation for a column or wall), supports engaged pilasters at the corners and is capped by a crowning cornice. Together, the three surviving façades, one side having been partially demolished, form a box-like mass articulated by strong horizontal and vertical divisions that reinforce the tomb’s utilitarian, almost mechanical character. Internally, the monument is entirely solid, filled with concrete, and contains no preserved burial chamber or accessible interior space for urns, suggesting that any remains were housed either externally or within upper architectural elements that have since been lost to time.

In plan, the tomb takes the form of an irregular trapezoidal shape, with its most striking decorative element, a multi-tiered frieze, wrapping around the upper portion of the structure. This frieze is composed of molded concrete elements designed to resemble equipment associated with bread production. The central register features elongated vertical cylinders, minimally echoing Corinthian column forms yet eerily modern in their simplicity.

Above this, the uppermost band consists of stacked hollow tubes and square recesses that evoke foculi, or small baking ovens, and pistoria, or kneading basins. These elements were cast directly in concrete and left exposed rather than being covered with a stone veneer, resulting in a bold, three-dimensional ornament whose rough, industrial texture contrasts sharply with the smoother travertine below. The effect emphasizes the monument’s industrial thematic focus through material honesty rather than classical embellishment, much like the brutalist styles of the late 20th century.

Reconstructions suggest that the upper level of the tomb may once have supported a gently sloping roof, which has not survived. Below, the undecorated socle gives way to the middle register of tall vertical cylinders, above which runs a narrow inscription band bearing a Latin text: “Est hoc monimentum margei [sic] vergilei eurysacis pistoris redemptoris apparet,” identifying the structure as the monument of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces, baker, contractor, and public servant.

The appearance of the monument’s missing eastern side remains a matter of speculation. During the 1838 demolition of the walls that had enclosed the tomb, archaeologists uncovered a marble relief depicting a man and a woman. The man wears a tunic and toga, while the woman is shown in a tunic and palla (a type of cloak associated with some women of that period), garments historians associate with Roman citizens of elevated social standing. Their bodies turn slightly toward one another, a pose that strongly suggests a marital relationship.

The same excavations yielded a marble inscription reading: “Fuit atistia uxor mihei femina opituma veixsit quoius corporis reliquiae quod superant sunt in hoc panario,” which translates to: “Atistia was my wife. She lived the life of an excellent woman. What remains of her body is in this breadbasket.” Also nearby, a marble urn sculpted in the form of a breadbasket (now lost) was discovered, leading most historians to associate all three elements: the relief, the inscription, and the urn, with Eurysaces and his household.

At the same time, these finds raise doubts. All of the sculptural and inscribed elements just described were made of marble, whereas the bulk of Eurysaces’ monument relies on simple travertine. Moreover, excavations in the area surrounding the tomb have yielded six additional epitaphs belonging to other bakers, including one commemorating a female baker, a pistrix. All of these date to the late first century BC, the same period during which Eurysaces erected his monument. While Eurysaces’ tomb is by far the most elaborate and imposing of these bakerly memorials, he would also have been the individual most financially capable of commissioning costly marble sculpture alongside his primarily travertine structure.

So what, then, can be inferred about Eurysaces from this accumulation of evidence? One of the first clues lies in his name, which is unmistakably Greek in origin. While the presence of Greeks in Rome during the late first century BC was entirely unremarkable, the absence of any patronymic formula, no claim to be “the son of” a named father, strongly suggests that Eurysaces had once been enslaved and later freed, becoming a libertus, or freedman. His emancipation was likely tied to his professional success as a baker, a reading that aligns neatly with the monument’s overwhelming emphasis on bread production.

This interpretation is further reinforced by Eurysaces’ self-identification in the inscription as a redemptor, or otherwise a state contractor, a role that would have required both technical expertise and substantial organizational capacity. Additionally, the omission of the letter L or “Lib” in his name on his funerary inscription, as was the custom for freed slaves then, is likely not an oversight, but an intentional rejection of the same custom, possibly Eurysaces declaring he is not defined by his former status, a stigma that followed many of his fellow freedmen for life.

In Roman society, it was common for highly skilled enslaved workers to be granted freedom and Roman citizenship, only to continue working in the same profession for their former owners. If Eurysaces had originally belonged to the imperial household, or at least to someone within Augustus’ elite circle, it would explain his subsequent position overseeing baking operations on behalf of the state. Under Augustus, the rationed distribution of free grain and bread to Rome’s citizens became a central pillar of public policy. Eurysaces’ probable involvement in this system would also clarify why he describes himself in his epitaph as a public servant, a designation that goes beyond mere private enterprise.

Additional support for this interpretation appears in the monument’s narrative frieze, which preserves at least thirty-one figures engaged in labor, dressed either in short tunics or shown bare-chested, alongside eleven officials identifiable by their togas and the record tablets they carry. Taken together, these scenes focus less on the act of baking itself than on the inspection, measurement, and verification of quality and quantity at each stage of production.

Such oversight is precisely what would be expected of a state contractor. Although no individual figure can be securely identified as Eurysaces, the imagery makes clear that the bakery depicted operated on a vast, industrial scale, subject to continuous supervision by representatives of the state, one of which would have been the man himself.

The full narrative sequence of the frieze, though partially lost, can still be reconstructed. It appears to begin on the monument’s south side with the arrival of grain at a workshop. Read from right to left, the scene shows the receipt and recording of the grain before it is milled into flour using a donkey-powered mill. The flour is then sieved and inspected for quality.

Rather than continuing seamlessly around the structure, the narrative resumes on the north side, again moving from right to left, where a horse-driven kneading machine is shown in operation, followed by scenes of dough being shaped and baked in an oven. Although the far left of the northern frieze is not fully preserved, the sequence continues on the west side, where finished loaves are transported in baskets, weighed, logged, and carried away.

Given this precise narrative and Eurysaces’ explicit pride in naming himself a pistor, or baker, the curious cylindrical forms that line the monument’s façade are almost certainly linked to breadmaking. Their exact function has long been debated. Proposals have ranged from grain measures and storage vessels to oven vents, but the prevailing view identifies them as representations of mechanical kneading machines, like those shown in the frieze itself. Archaeological evidence from sites such as Pompeii and Ostia supports this interpretation, as excavated kneading devices from these cities closely resemble the forms depicted on Eurysaces’ tomb.

Further confirmation lies within the cylinders themselves. Each hollow form contains a small square recess at the back, often discolored by rust, suggesting that a metal fitting was once mounted there. This projecting element, now lost, would have been essential to the operation of a mechanical kneader, likely serving as part of the turning mechanism for the dough. At the time the tomb was constructed, such machines were relatively recent technological innovations. Eurysaces’ decision to monumentalize them implies a deliberate desire to showcase his embrace of new, efficiency-enhancing technology and to associate himself with the vanguard of large-scale, mechanized production.

Evidence for the physical location of such an enterprise exists just south of the tomb itself. Archaeological investigations conducted between 1838 and 1842, and again from 1954 to 1956, uncovered a substantial milling complex in the immediate area. The site contained two large halls and, nearby, at least seven animal-powered mills, along with multiple grinding stones, basins, and large storage jars known as dolia.

This complex appears to have been in operation from at least the mid–first century BC, roughly contemporary with the construction of Eurysaces’ monument, until 52 AD, when it was dismantled to make way for the construction of new aqueducts. Although no ovens were identified during the excavations, the presence of an industrial flour mill, combined with funerary inscriptions for at least six other bakers from the same period found nearby, strongly suggests a concentrated zone of large-scale bread production rather than mere coincidence.

This tomb belongs to a broader phenomenon of lavish funerary monuments commissioned by former slaves living in the Roman Empire. Freedom might be awarded by a master in recognition of exceptional service or purchased through a peculium, the personal earnings enslaved individuals were sometimes allowed to accumulate. Even after manumission, freedmen typically remained bound by obligations to their former owners, as was likely the case for Eurysaces. Nevertheless, their professions were a source of pride, since skilled labor was often the very means by which freedom had been attained. For this reason, freedmen frequently invested in conspicuous tombs such as that of Eurysaces.

Lacking established ancestral lineages outside of their former masters’ families, a critical marker of status in Roman society, these monuments may have functioned as deliberate attempts to inaugurate a family history, creating a visible and enduring legacy for future generations to return to and witness, likely why something as stigmatic as the letter L was completely missing from the final testament to the baker’s achievements in life.

The tomb was later absorbed into Rome’s defensive infrastructure when it was directly incorporated into the fortifications of the Aurelian Walls. Over time, the monument became part of the city’s physical fabric and, by the third century AD, was largely buried beneath layers of sediment and structural infill. This process of integration inadvertently preserved much of the tomb while removing it from public view for centuries. Subsequent alterations, including the construction of additional bastions under Emperor Honorius in the early fifth century AD, further obscured the original form of the monument beneath accumulated urban debris.

Eurysaces’ tomb occupies a highly strategic site at the junction of two major ancient roads, the Via Labicana and the Via Praenestina, both of which led directly into Rome. The structure rises roughly 33 feet, or about 10 meters, above the original ground level and today stands in the shadow of the much larger Porta Praenestina, now known as the Porta Maggiore, erected in 52 AD under Emperor Claudius to carry the Aqua Claudia and Anio Novus aqueducts overhead.

Although the tomb’s trapezoidal footprint may initially appear irregular, the form reflects a pragmatic response to the constrained wedge of land between the two roads. This area lay just outside the city’s sacred boundary, within which adult burials were prohibited, and was therefore densely populated with funerary monuments. Eurysaces’ choice of location underscores his desire for visibility: anyone entering or leaving Rome along these principal routes would have been forced to confront his monument and thus his life’s contributions to the city of Rome.

The tomb was rediscovered in 1838 during the demolition of the Honorian bastions at the Porta Maggiore, a project ordered by Pope Gregory XVI as part of broader efforts to improve circulation and urban planning in the area. Excavations carried out between 1838 and 1842 under the direction of the archaeologist Luigi Canina systematically exposed the structure. Canina documented the tomb’s trapezoidal base, which had been embedded within the foundations of the gate, and recorded its unusual architectural features through detailed measurements and drawings.

His findings demonstrated that the monument’s survival owed much to its durable concrete core and travertine facing, which had allowed it to function as a structural nucleus within medieval and early modern fortifications. Miraculously, Pope Gregory XVI allowed it to remain standing, where it has remained to this day as one of Rome’s many ancient landmarks.

Everything we know, and possibly will ever know, about Eurysaces himself is derived from this single monument. More significantly, the tomb stands as the most important visual record of bread production in the Roman world. In practical terms, it has contributed more to modern understanding of how baking functioned under Roman rule than any surviving literary description. The reliefs preserve processes, tools, and organizational structures that ancient texts either ignore or mention only in passing, making the tomb not merely commemorative but documentary.

The monument serves as a declaration of the craft as much as of the man. It makes no effort to disguise or embellish its material through surface ornament. The stone is allowed to exist on its own terms, without applied texture, illusionistic carving, or decorative refinement. In this respect, the tomb anticipates later architectural attitudes that would prize material honesty and exposed structure. Much like brutalist architecture’s infamous use of concrete, the Tomb of the Baker communicates its meaning directly, without aesthetic mediation.

While not quite brutalism in any strict sense, the monument is no less radical. It remains an entirely singular example of mimetic architecture in the ancient world. In its own time, it must have been startling. Even today, the idea of encountering a tomb shaped like an industrial dough mixer would feel jarringly out of place in a cemetery, no less provocative now than Eurysaces’ monument would have been two thousand years ago.