Founded in 2018, COMRADE Gallery has grown into one of the most compelling new archives of Eastern Bloc visual design. Since the gallery’s inception, founder Stephane Cornille has traveled across several former Soviet republics and beyond, meeting with the artists who designed these prints (or their descendants) and bringing to light stacks of work long hidden in studio drawers, forgotten archives, and apartments.

Between Control and Expression

The works now on view and for sale through COMRADE offer more than aesthetic appeal, they provide a rare glimpse into an understudied microcosm of design history. For an era commonly associated with stringent censorship and ideological uniformity, these posters tell a more varied and unexpected story. Some promote familiar political themes for the times such as space exploration, nuclear non-proliferation, and worker safety, while others lean into the abstract, eccentric, or outright bizarre. A 1988 anti-bribery poster from Latvia, for example, depicts a pigeon dressed in a suit and tie, a piece of bread clamped in its beak. Below it, the text reads: “I cannot compromise my principles.” Ostensibly a public ethics campaign, but one executed with a deadpan surrealism.

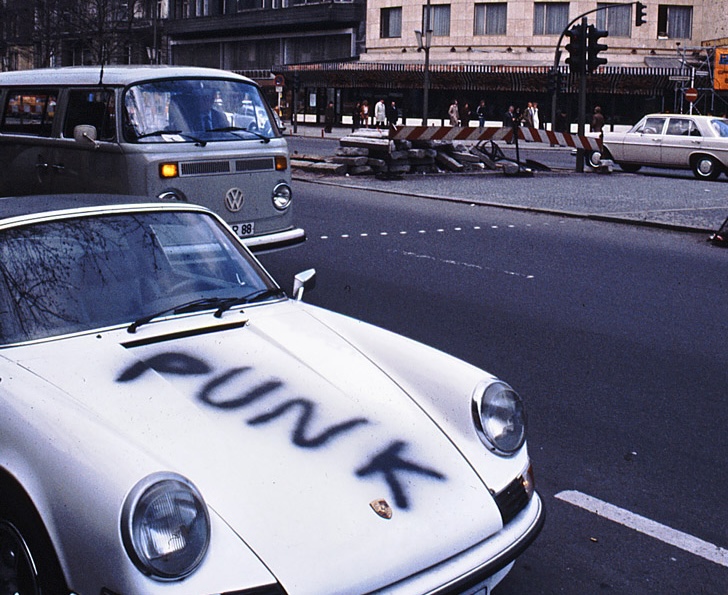

This blend of messaging and ambiguity speaks to the conditions under which many of these posters were made, created within the framework of the state, but often shaped by individual expression, curiosity with western trends, or aesthetic experimentation. Far from being tools of propaganda alone, these works reflect a visual culture that was constantly negotiating the space between control and creativity.

More Than Politics

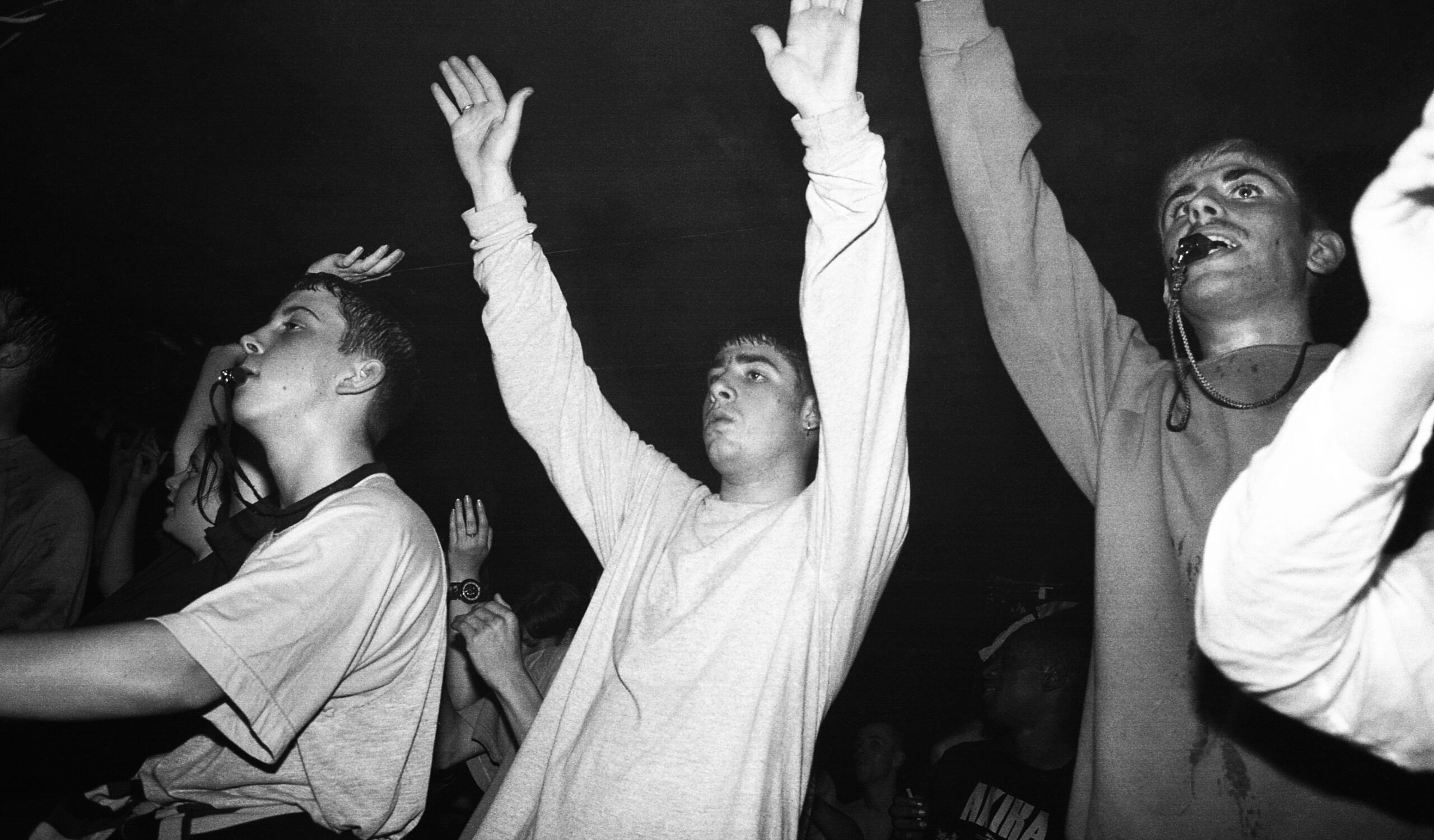

The COMRADE collection also highlights a wide spectrum of poster design that extends well beyond politics and into daily life and mass culture: vivid advertisements for circuses, jazz festivals, avant-garde theater, and film screenings all feature prominently. These works reveal an often-overlooked facet of cultural life in the Eastern Bloc: a state-sponsored, yet surprisingly experimental public visual culture.

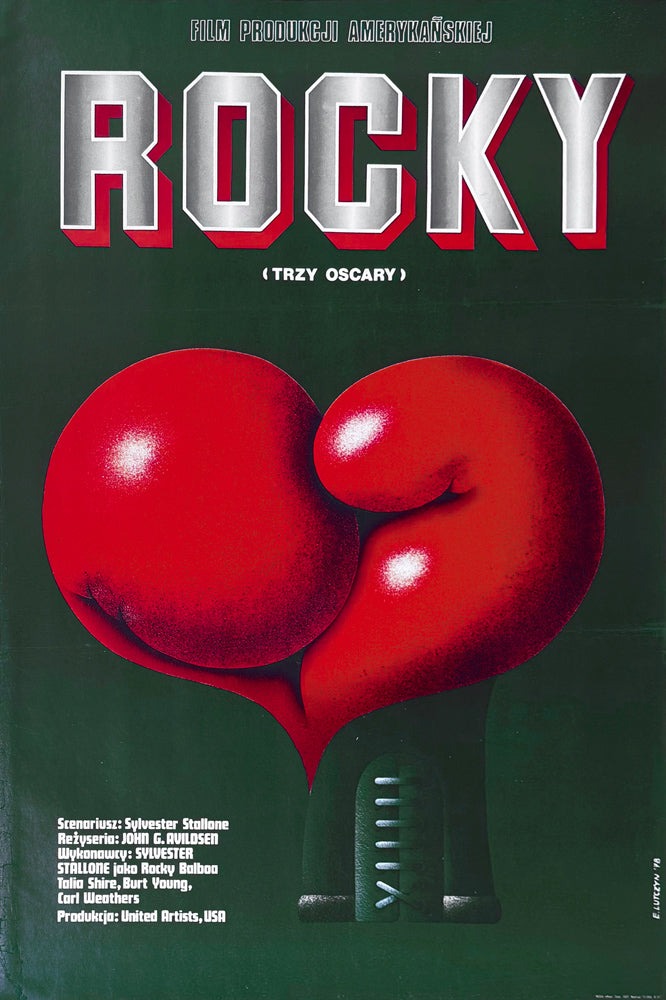

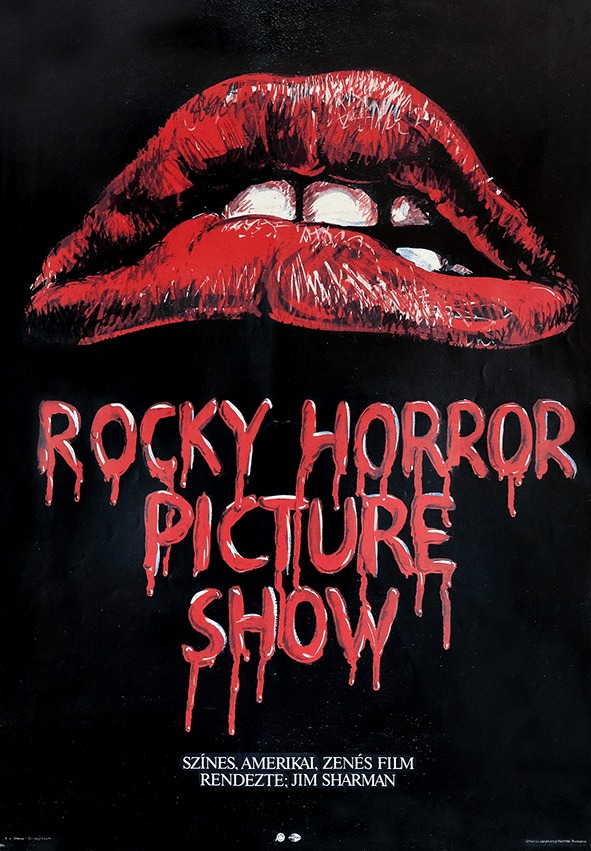

A particularly surreal element within this space regards the arrival of Western films. While most Soviet states strictly limited or outright banned Western media, some countries promoted a more relaxed approach to relations with the outside world. Yugoslavia, for example, thanks to Tito’s break with Stalin, pursued a non-aligned path that opened it to both Western markets and influences. Hungary, Poland, and East Germany allowed limited screenings of U.S. films such as Star Trek, Rocky, Jaws, and even the Rocky Horror Picture Show. The release of these films served as a kind of cultural pressure release, proof that the state could be cosmopolitan too.

Designing Without Reference

When these films were being released, local artists were occasionally tasked with promoting Western films. However, there was a catch: they were not permitted to look at Hollywood’s original promotional materials, and in many cases they had never been given the chance to see the films themselves prior to making the designs.

This restriction gave rise to a uniquely localized form of film poster: imaginative, interpretive, and often wholly unrelated to the original narrative. Designers often worked from stills and vague plot summaries alone, producing images that resembled fan-made art prints more than official marketing tools. A 1990 Russian poster for Star Wars reimagines Darth Vader with a panther-like face, surrounded by alien creatures in jagged geometric forms. The result is striking: part science fiction, part folk hallucination, and wholly detached from any studio-approved visual language.

A Grey Zone for Innovation

Behind these strange and inventive designs was a precarious negotiation. Output was monitored by official state institutions, and the balancing act that was approval could hinge on arbitrary decisions or shifting ideological moods. Some artists learned to wait out the censors, banking on the fact that scrutiny would lessen as the regime aged and priorities shifted. By the late 1980s, in many parts of the Bloc, the grip of centralized cultural control had loosened enough for more daring or abstract work to pass unnoticed.

In Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and the Baltic States, visual design and creativity in general evolved into a kind of sanctioned grey zone, a place where visual experimentation was tolerated, as long as it avoided overt political messaging. Many artists used this to their advantage. Some cultivated distinctive, highly personal styles that gained recognition both at home and abroad. A few became minor celebrities in art and design circles. Others maintained a more discreet presence, fading into obscurity or retreating into their personal lives as soon as socialism ended in their countries. In either case, posters became more than functional objects, they were a creative outlet for designers working within the contradictions of a controlled but often inconsistent system.